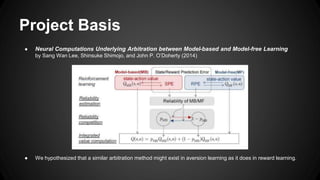

This document summarizes a study on pain avoidance learning and the interaction between model-based and model-free systems. The study used a two-layer Markov decision task with different block conditions to test whether participants used model-based or model-free strategies. Results showed participants were more likely to use a model-free strategy in the flexible block condition and a model-based strategy in the specific block condition. Modeling results supported the existence of both systems in aversion learning, though parameter differences suggest a more dynamic arbitration process than in reward-based learning. The conclusion was that while arbitration between the systems shares similarities to reward learning, there are subtle differences in aversion.