The document outlines an assignment for a parenting class flyer due in week 2, emphasizing the importance of addressing parenting expectations and styles influenced by various factors. It details requirements, including the class purpose, five distinct topics with supporting resources, and a creative approach to attract new parents, ensuring academic standards are met. Additionally, the document discusses cultural variations in parenting, highlighting how beliefs and behaviors differ across cultural contexts and their implications on parenting practices.

![MarcH.Bornstein,ChildandFamilyResearch,EuniceKennedyShriv

erNational Institute

of Child Health and Human Development, Suite 8030, 6705

Rockledge Drive, Bethesda

MD 20892-7971, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research supported by the Intramural Research Program of the

NIH, NICHD. I thank

P. Horn and C. Padilla.

REFERENCES

Barrett, J.,&Fleming,A.S.

(2011).Allmothersarenotcreatedequal:Neuralandpsychobiologica

lperspectives

on mothering and the importance of individual differences.

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52,

368–397.

Bornstein, M. H. (1989). Cross-cultural developmental

comparisons: The case of Japanese–American infant

and mother activities and interactions. What we know, what we

need to know, and why we need to know.

Developmental Review, 9, 171–204.

Bornstein, M. H. (Ed.). (1991). Cultural approaches to

parenting. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bornstein, M. H. (1995). Form and function: Implications for

studies of culture and human development.

Culture and Psychology, 1, 123–137.

Bornstein, M. H. (2001). Some questions for a science of

“culture and parenting” (... but certainly not all).

International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-24-2048.jpg)

![BS1 2LY, UK

E-mail:

[email protected]

Abstract

Background Parenting influences child outcomes but does not

occur in a vacuum. It is influenced

by socio-economic resources, parental health, and child

characteristics. Our aim was to investigate

the relative importance of these influences by exploring the

relationship between changing

parental health and socio-economic circumstances and changes

in parenting.

Methods Data collected from the Avon Longitudinal Study of

Parents and Children were used to

develop an eight-item parenting measure at 8 and 33 months.

The measure covered warmth,

support, rejection, and control and proved valid and reliable.

Regression analysis examined changes

in financial circumstance, housing tenure, marital status, social

support, maternal health and

depression, and their influence on parenting score. The final

model controlled for maternal age,

education, and baseline depression.

Results Most mothers reported warm, supportive parenting at

both times. Maternal depression was](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-31-2048.jpg)

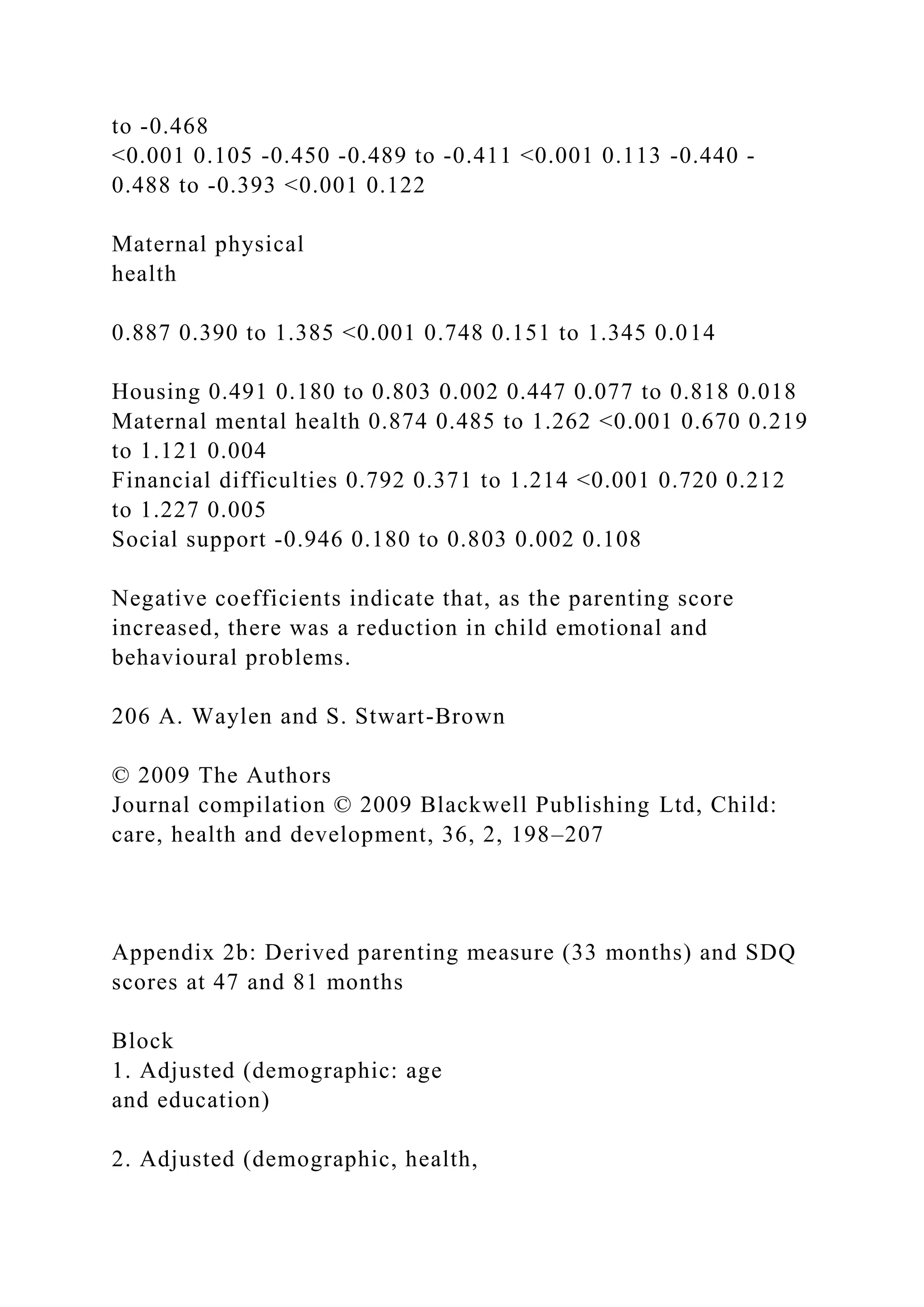

![parenting variable at 8 and 33 months with another parenting

measure collected on the cohort [HOME Inventory (Bradley &

Changes in parenting over time 199

© 2009 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child:

care, health and development, 36, 2, 198–207

Caldwell 1995)] and the Strengths and Difficulties Question-

naire (SDQ) (Goodman 2001) at 47 and 81 months.

The results of univariate linear regression analysis showed

that the derived parenting measure predicted SDQ scores at

both 47 and 81 months (P < 0.001) and remained predictive

(P < 0.001) after adjusting for confounding variables (Appen-

dices 2a & b). Negative coefficients indicate that, as parenting

score increased, child emotional and behavioural problems were

reduced: a point increase in parenting score predicted a reduc-

tion in SDQ score of 0.4–0.5 after adjustment for confounders.

To assess change over time, scores for the derived parenting

variable at 8 months were subtracted from scores at 33 months

giving a normally distributed change score ranging from -17 to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-39-2048.jpg)

![+17. A negative score (higher at 8 than 33 months) indicates

deterioration in parenting over time and vice versa.

Identification of factors predicting parenting

Correlations were obtained between parenting scores and

various socio-demographic and parental variables available for

the cohort children and indicated as relevant in the literature.

Key predictors of parenting score were maternal age and edu-

cation. Ethnic group was not a significant predictor possibly

because there were several ethnic categories with very small

membership. Amongst the range of potentially changeable

factors, financial circumstances, housing tenure, marital status,

social support (emotional, financial, and practical support from

partner, family, friends, or the state), and maternal general

health and depression [as measured by the Edinburgh Post-

Natal Depression Scale – EPDS (Matthey et al. 2001)]

correlated

with parenting scores (P < 0.001). Each of these variables was

dichotomized: (1) mothers either found it difficult to afford

three or more from a list of five items or not; (2) they owned

their own homes or not; (3) they were married or not; (4) they](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-40-2048.jpg)

![Attrition analysis

At 8 months, mothers who would drop out of the study by 33

months were more likely than those who remained to have

financial difficulties [10.4% (N = 233) vs. 8.0% (N = 725),

respectively; (c2 = 12.83, P < 0.001)]; be unmarried [6.8% (N

= 153) vs. 5.0% (N = 451); (c2 = 9.92, P = 0.002)] and be living

in rented accommodation [36.9% (N = 824) vs. 19.4%

(N = 1750); (c2 = 300.18, P < 0.001)]; to perceive little or no

social support for themselves [7.1% (N = 140) vs. 4.0% (N =

337); (c2 = 37.35, P < 0.001)]; and to be depressed [14.6% (N

= 326) vs. 10.5% (N = 939); (c2 = 27.88, P < 0.001)]. Mothers

who dropped out of the study had a slightly lower parenting

score at 8 months [28.1 vs. 28.3; (N = 11 068); (t = 2.95, P <

0.001)] than those who remained. There were no differences in

the general health of remaining mothers compared with those

who dropped out: 94.1% (N = 2138) compared with 94.6% (N

= 8563) rated themselves as always or mostly well (c2 = 5.11, P

= 0.164). Results reported here concern families with data at

both 8 and 33 months.

Changes in circumstance over time

Between 8 and 33 months, marital status changed for 3% (N =

252) of mothers: 2% (163) were no longer in a marital rela-

tionship by 33 months whereas 1% (89) entered a relationship.

Depression status changed for 15% (1360) of mothers: 9.8%

(895) became depressed by 33 months whereas 5.1% (465)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-44-2048.jpg)

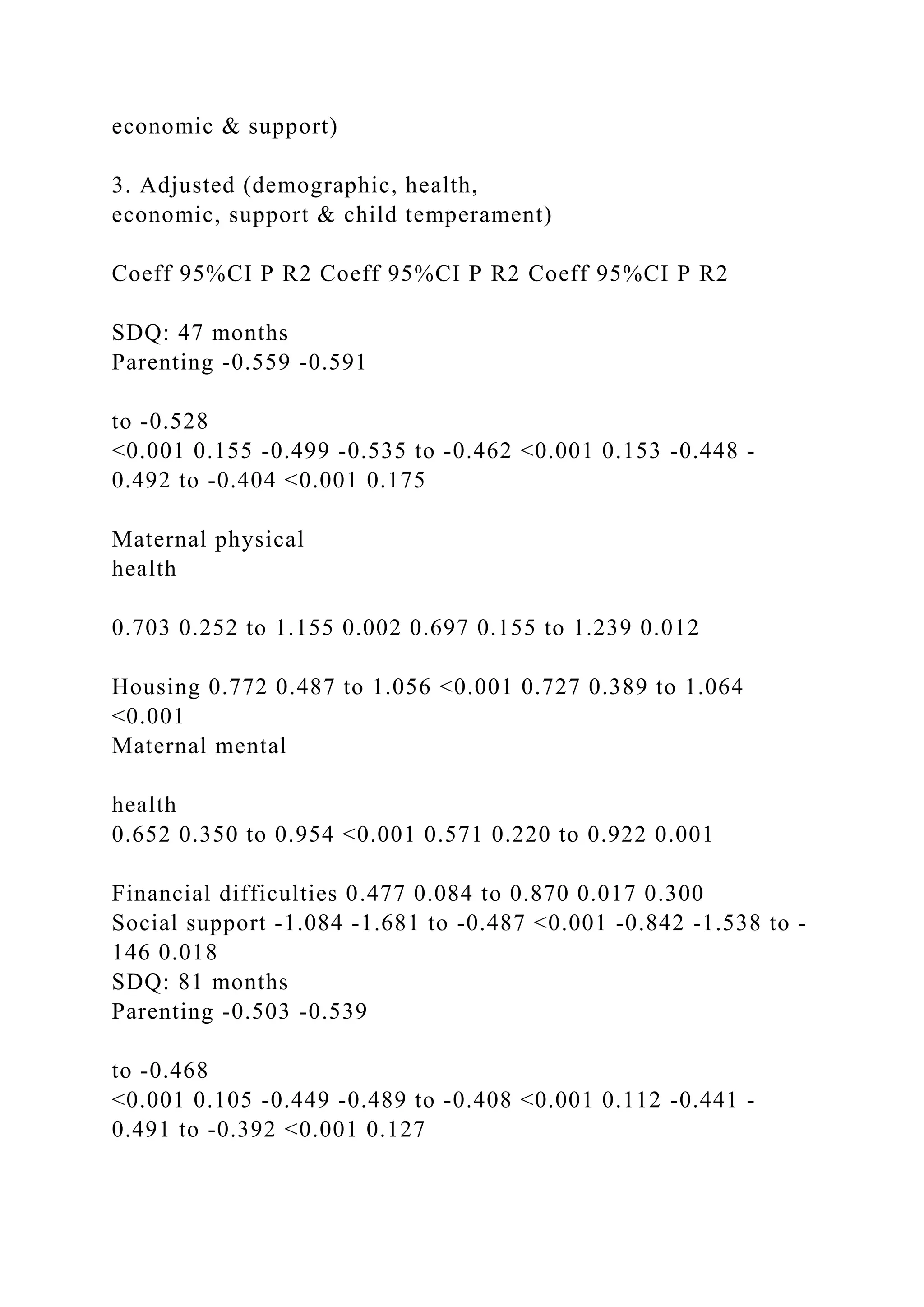

![0

.0

3

<0

.0

0

1

202 A. Waylen and S. Stwart-Brown

© 2009 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child:

care, health and development, 36, 2, 198–207

financial status, health, or support remained stable between 8

and 33 months. Negative coefficients indicate a reduction in

parenting score and positive coefficients indicate an increase.

In the final, fully adjusted model, parenting score reduced by

0.14 [95% CI (-0.06–0.20); P < 0.001] when financial circum-

stances deteriorated, but improving financial circumstances did

not predict an improvement in parenting score (P = 0.213).

Increased social support predicted improvement in parenting

score by 0.16 [95% CI (0.02–0.30; P = 0.027)] but reduced

social

support was not predictive (P = 0.733). Improvements and dete-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-102-2048.jpg)

![riorations in depression score predicted changes in parenting

as expected: an improvement in (lessening of ) depression

increased parenting score by 0.20 [95% CI (0.18–0.29); P <

0.001] and worsening depression reduced the parenting score

by -0.14 [95% CI (-0.23–0.04); P = 0.004]. Parenting score

increased by 0.11 [95% CI (0.02–0.20); P = 0.02] when general

health improved, but there was no effect on parenting score

when general health worsened (P = 0.548).

Discussion

On average, parenting scores varied with maternal age and edu-

cation to a small extent and changed very little over the period

of time examined in this study. Mothers mainly reported warm,

supportive parenting at both time points, a finding consistent

with earlier research showing stability of positive parenting in

early childhood (Dallaire & Weinraub 2005). Where changes in

parenting occur, they represented a reduction in score over

time. This may reflect the age and stage of the child (Holden &

Miller 1999; Verhoeven et al. 2007): as children get older they

may be perceived as being less easy to look after.

Within the context of these relatively small changes, results](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-103-2048.jpg)

![1995)]. The HOME Inventory focuses on aspects of parenting

relating to cognitive development as opposed to relationship

quality and so the modest correlation we observed was appro-

priate. More impressively, our measure predicted behavioural

outcomes in later childhood accounting for 10% of the variance

in SDQ scores (Goodman 2001) with the 33-month measure

being more predictive than the 8-month measure. This finding

suggests that, despite limitations, our measure captured aspects

of parenting relevant to child outcomes and early years policy.

Worsening parental health (Frank 1989; Armistead et al.

1995) has been associated with disrupted parenting and our

findings regarding depression are consistent with these earlier

studies. Our results are also consistent with studies showing

that

financial deprivation is associated with deterioration in parent-

ing (Conger et al. 1992, 1993; McLoyd 1998; National Institute

of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care

Research Network 2005). Amongst families whose financial cir-

cumstances improved, some may have returned to a predepri-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-108-2048.jpg)

![changes. JensenPeña

256 JENKINS

and Champagne (2012) show that rats that experience low

licking and grooming by

their mothers have reduced expression of hippocampal

glucocorticoid receptors and

increased DNAmethylation within theglucocorticoid promoter

region. This means that

the effect of a stressful environment has been to “silence” the

gene. The elegant desig-

nation of these pathways illustrates the way in which

environmental influences become

embedded into the functioning of the organism. Pollak (2012)

presents data across mul-

tiple brain systems showing effects of abusive environments.

Effects are evident in

volumeof theorbital frontalcortexaswellas thecerebellum,

theneuroendocrinesystem

(including both oxytocin and the arginine vasopressin [AVP]

system) as well as neural

responses to the processing of anger. Perceptual and attentional

biases develop such

that abused children identify anger more rapidly, they attend to

it more, they have trou-

ble disengaging from angry faces, and, as a consequence of

privileging anger within the

cognitive system, other aspects of cognition become less

efficient. Like Bornstein (2012),

Pollak (2012) shows us that the organism changes to be able to

meet the demands of the

specific environment to which it is exposed. Research programs

that cross the bound-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-130-2048.jpg)

![found that about 20% of the variation in negativity and 29% of

the variation in positiv-

ity was attributable to the individual, with about 35% of this

individual effect being

explained by genetic influence (Rasbash, Jenkins, O’Connor,

Tackett, & Reiss, 2011).

Thus, parents and children do show some consistency in

relational behavior as they

interact with different family members, but not a huge amount.

Most of the action (55%

of the variation in negativity and 49% in positivity) is within

the unique combination

of the two people in the dyad. Thus, some dyads tolerate one

another well, whereas

other dyads do not manage the accommodations necessary for a

well-attuned relation-

ship.Thestrongerdyadversus individualeffect suggests

thatamajor focus inparenting

should be on the processes by which parents and children

flexibly accommodate to one

another’s idiosyncrasies (Grusec, 2011).

In summary, this exciting series of articles shows us that a

multilevel framework,

from biology to macrosystems, in which we can model both

reciprocal and contingent

processes, is necessary to understand the complexity in the

development of parenting.

AFFILIATION AND ADDRESS

Jennifer Jenkins, Human Development and Applied Psychology,

University of Toronto,

252 Bloor St. W., Toronto, ON M5S 1V6 Canada. E-mail:

[email protected]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-137-2048.jpg)

![MULTILEVEL DYNAMICS OF PARENTING 259

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Jennifer Jenkins is grateful to the Canadian Institutes for Health

Research, The Atkinson

Charitable Foundation and the Social Sciences and Humanities

Research Council for

support.

REFERENCES

Atzaba-Poria, N., & Pike, A. (2008). Correlates of parental

differential treatment: Parental and contextual

factors during middle childhood. Child Development, 79(1),

217–232.

Baker-Henningham, H., Scott, S., Jones, K., & Walker, S.

(2012). Reducing child conduct problems and pro-

moting social skills in a middle-income country: Cluster

randomized controlled trial. British Journal of

Psychiatry, April 12. [Epub ahead of print].

Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2011).

Differential susceptibility to rearing envi-

ronment depending on dopamine-related genes: New evidence

and a meta-analysis. Development and

Psychopathology, 23(1), 39–52.

Barrett, J., & Fleming, A. S. (2011). Annual research review:

All mothers are not created equal: Neural and

psychobiological perspectives on mothering and the importance

of individual differences. Journal of Child

Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(4), 368–397.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-138-2048.jpg)

![these relationships. A fuller account of the ethical significance

of these relationships will

require further investigation into what we should deem to be

children’s responsibilities

withinthem.

Inaddition,currentworkexploringthebiologicalaspectsofparenting

may

inform our understanding of the most appropriate assessment of

the ethical dimension

of parenting in different circumstances, including decidedly

suboptimal circumstances,

rather than in the more resource rich environments I have been

assuming. More under-

standing of the biological bases of parenting behavior might

also lead us to greater

understanding of when social intervention or optional forms of

social support may

be called for, to support minimally decent parenting. Finally,

philosophical reflection

on some of this research may help us understand the extent to

which interventions in

children’s lives may be required to support their future ability

to parent well.

AFFILIATION AND ADDRESS

Amy Mullin, University of Toronto, Office of the Dean,

University of Toronto

Mississauga, 3359 Mississauga Rd. N., Mississauga, ON, L5L

1C6 Canada. E-mail:

[email protected]

THE ETHICAL AND SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE OF

PARENTING 143](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignmentinstructionsweek2duringweeks1and2youhaveex-221026125549-927e0d9d/75/Assignment-Instructions-Week-2During-weeks-1-and-2-you-have-ex-docx-166-2048.jpg)