The document discusses asset and liability management focusing on depository institutions, including commercial banks, savings institutions, and credit unions, as well as securities brokerage firms and investment banks. It highlights the evolution of products offered by financial institutions from 1950 to 2016, emphasizing increased consolidation, changes in regulations, and the impact of technology on banking. Significant trends, regulatory changes, and the financial performance of these institutions over time are also reviewed.

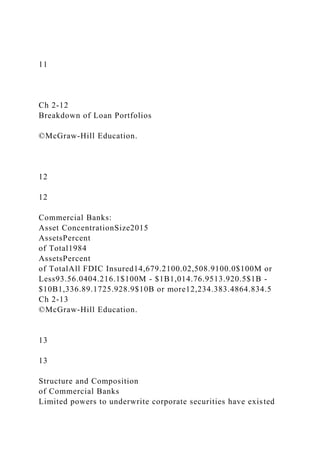

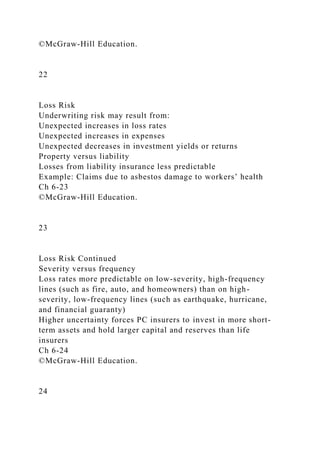

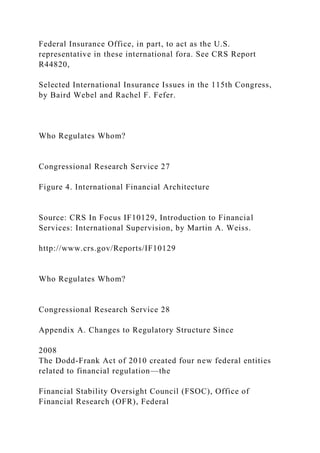

![and securitizers)

credit rating

agencies and research analysts);

changes) and market utilities

(e.g.,

clearinghouses) where securities are traded, cleared, and settled;

and

security-based swaps).

The SEC is not primarily concerned with ensuring the safety

and soundness of the firms it

regulates, but rather with “protect[ing] investors, maintain[ing]

fair, orderly, and efficient

markets, and facilitat[ing] capital formation.”

26

This distinction largely arises from the absence of

government guarantees for securities investors comparable to

deposit insurance. The SEC

generally does not have the authority to limit risks taken by

securities firms,

27

nor the ability to

prop up a failing firm.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assetandliabilitymanagementfin6102ferriterspring2018-221015032421-8db7f4ac/85/Asset-and-Liability-ManagementFin6102Ferriter-Spring-2018-docx-107-320.jpg)

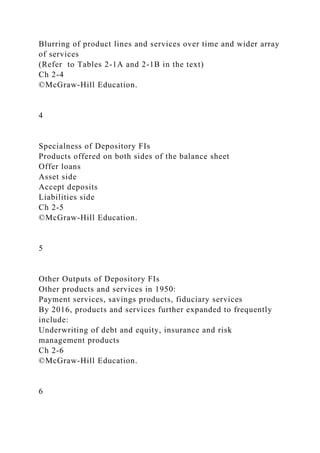

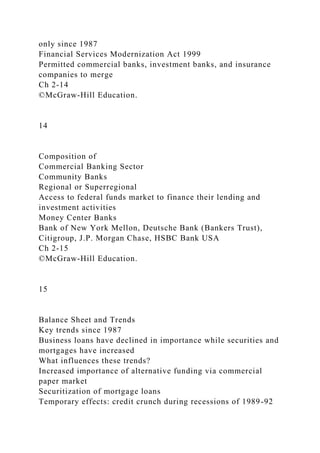

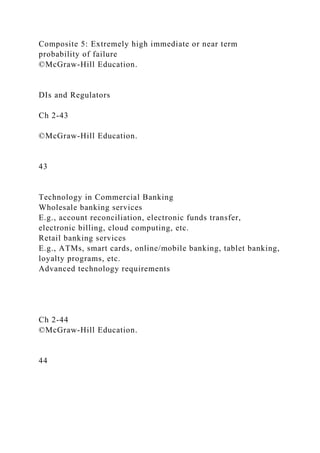

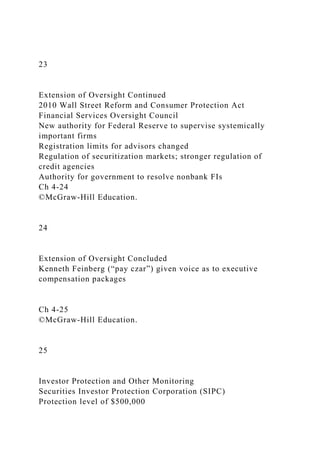

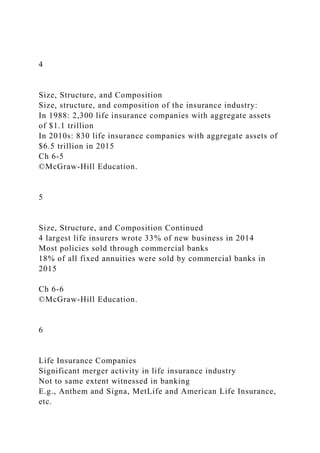

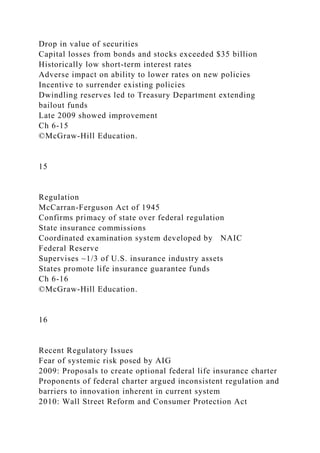

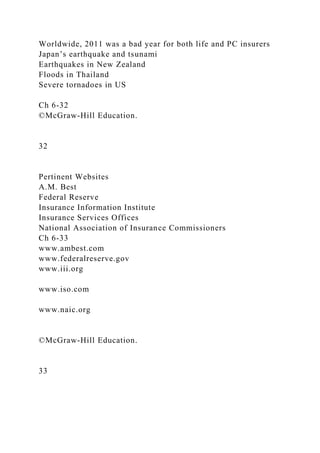

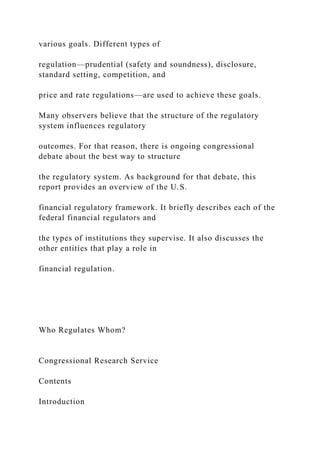

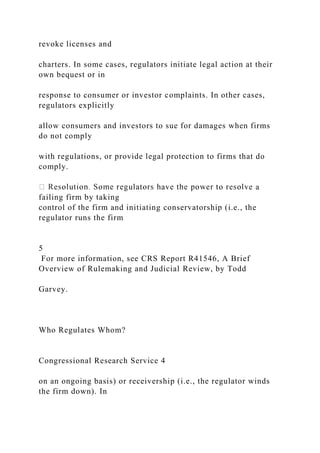

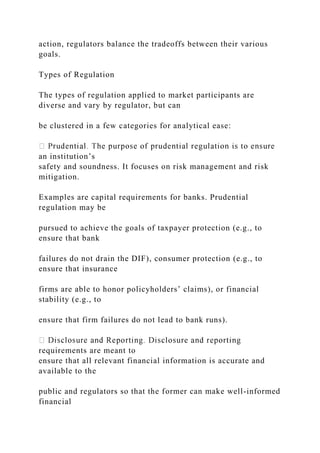

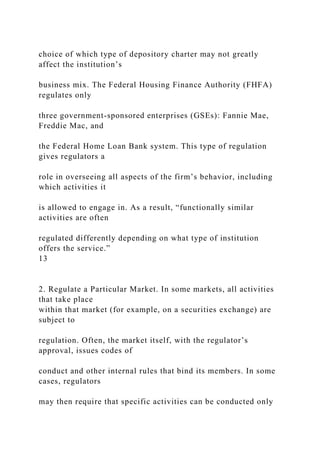

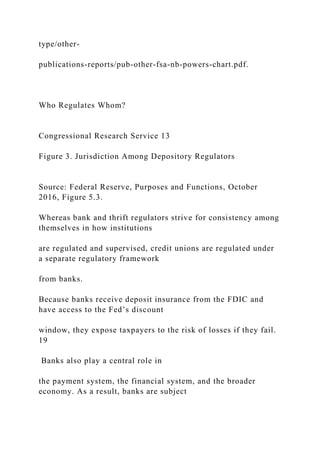

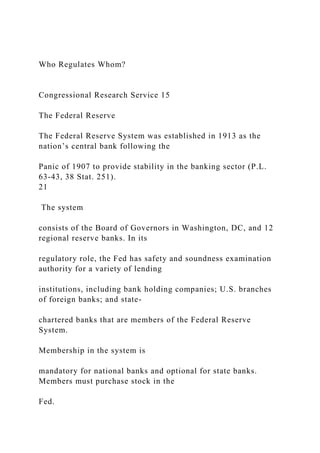

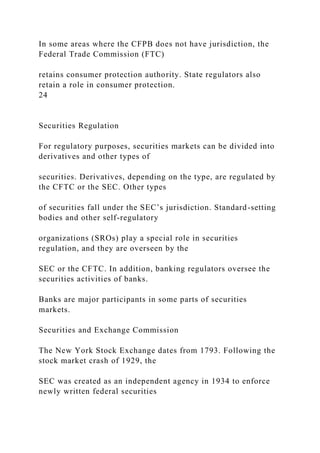

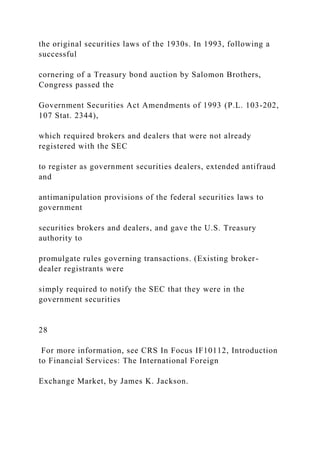

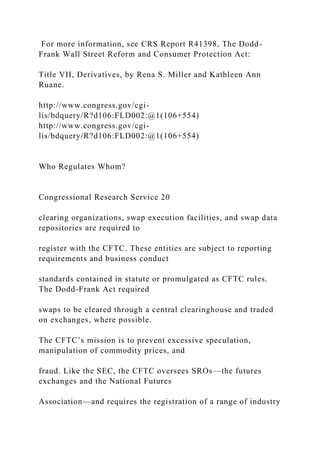

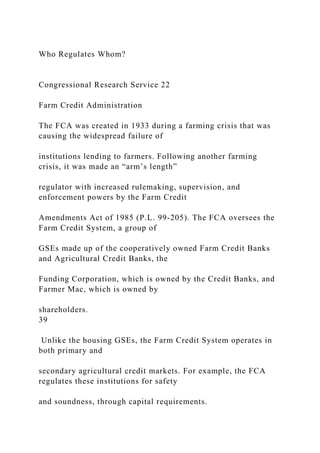

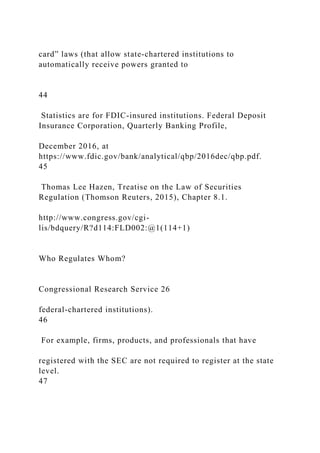

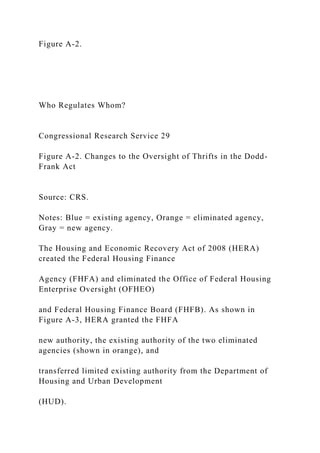

![Figure A-3. Changes to the Oversight of Housing Finance in

HERA

Source: CRS.

Notes: Blue = existing agency, Orange = eliminated agency,

Gray = new agency.

Who Regulates Whom?

Congressional Research Service 30

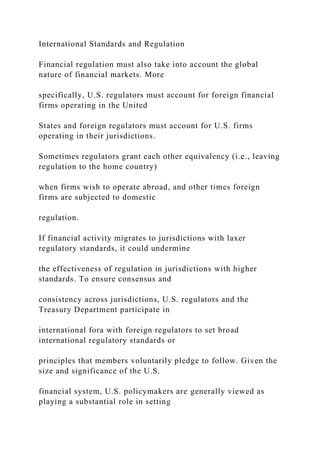

Appendix B. Experts List

Table B-1. CRS Contact Information

Author Title Telephone Email Regulation of:

Darryl

Getter

Specialist in Financial

Economics

7-2834 [email protected] Consumer protection, credit

unions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assetandliabilitymanagementfin6102ferriterspring2018-221015032421-8db7f4ac/85/Asset-and-Liability-ManagementFin6102Ferriter-Spring-2018-docx-147-320.jpg)

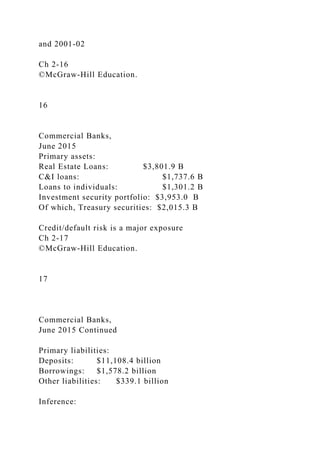

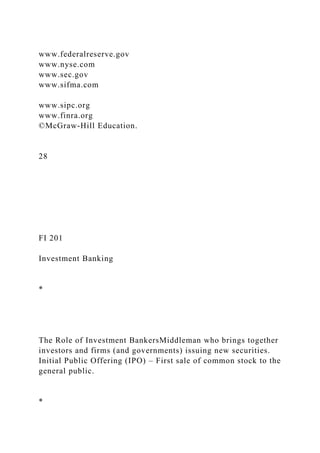

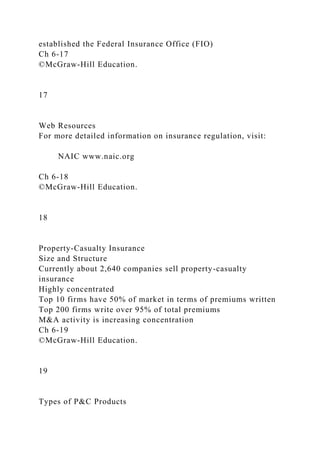

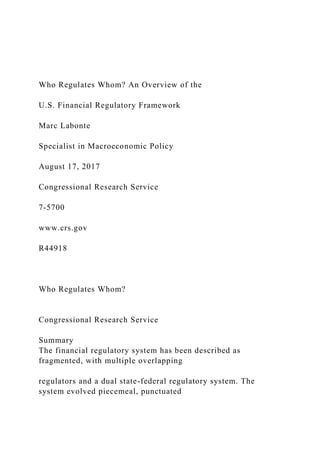

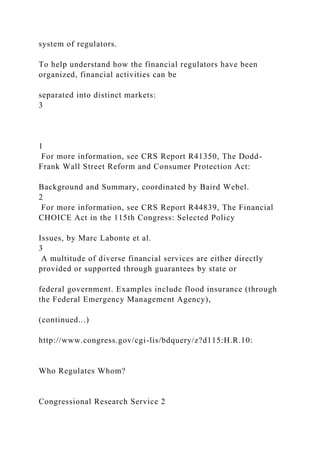

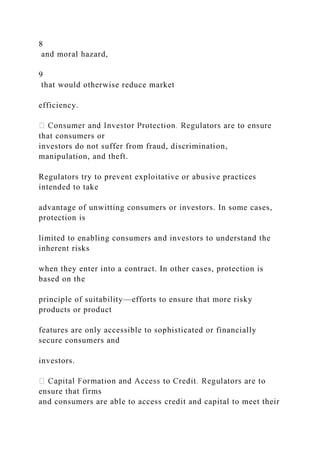

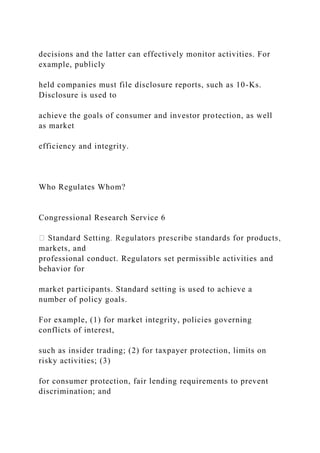

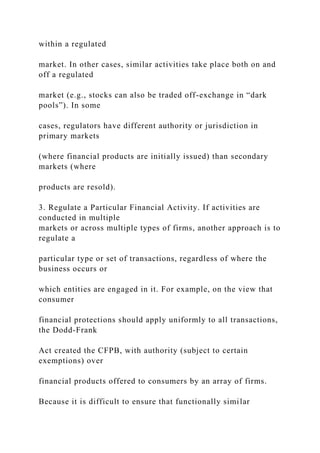

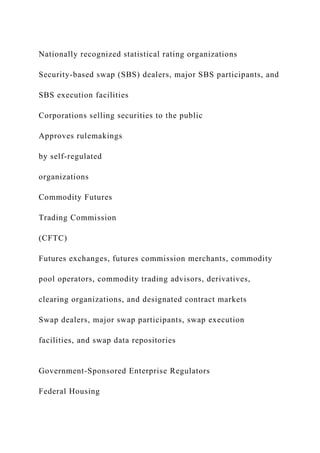

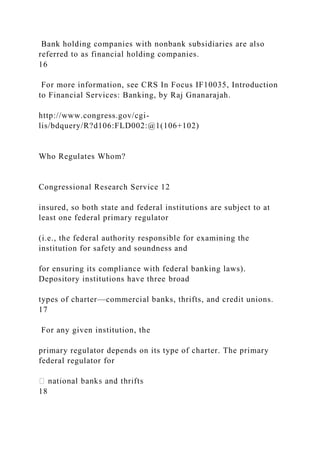

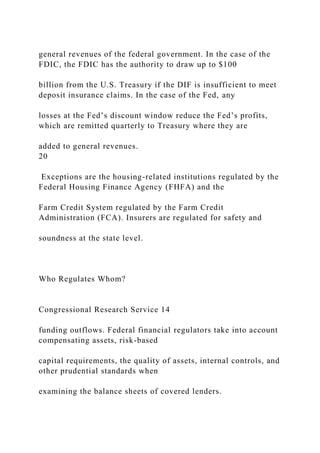

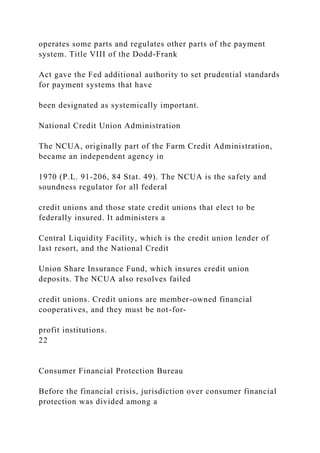

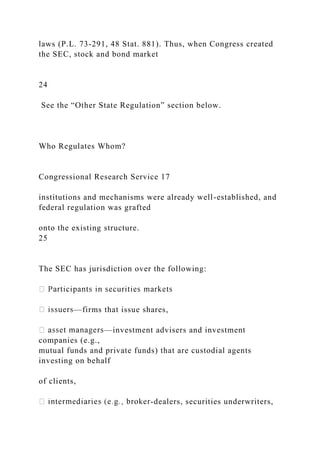

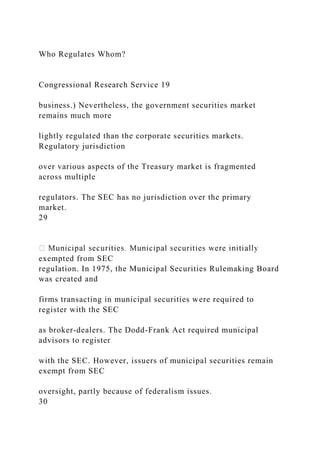

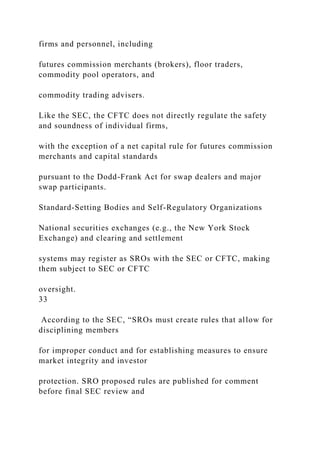

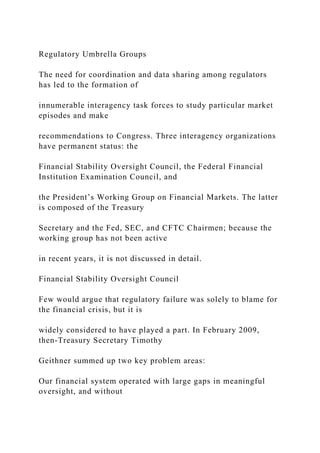

![Raj

Gnanarajah

Analyst in Financial

Economics

7-2175 [email protected] Accounting and auditing,

deposit insurance

Marc

Labonte

Specialist in

Macroeconomic Policy

7-0640 [email protected] Financial stability, Federal

Reserve, regulatory

structure

Rena Miller Specialist in Financial

Economics

7-0826 [email protected] Derivatives

James

Monke](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assetandliabilitymanagementfin6102ferriterspring2018-221015032421-8db7f4ac/85/Asset-and-Liability-ManagementFin6102Ferriter-Spring-2018-docx-148-320.jpg)

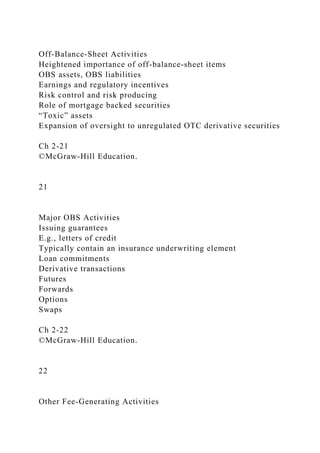

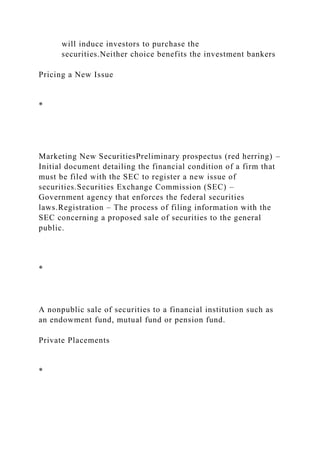

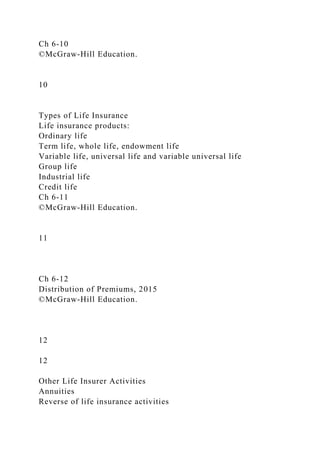

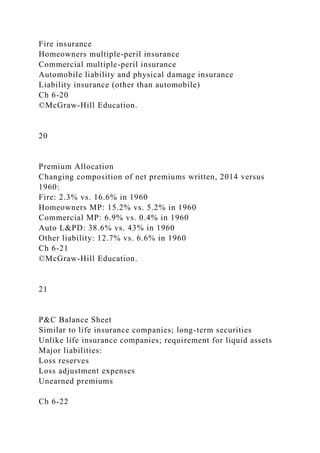

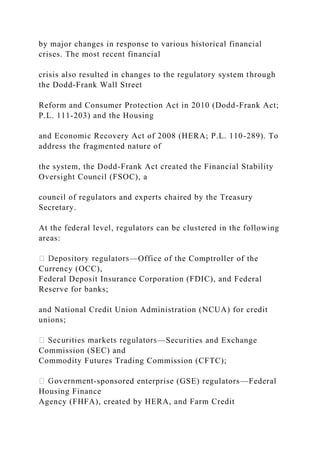

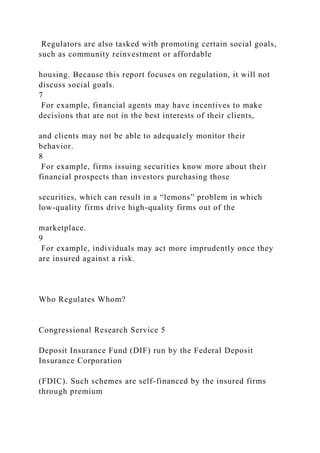

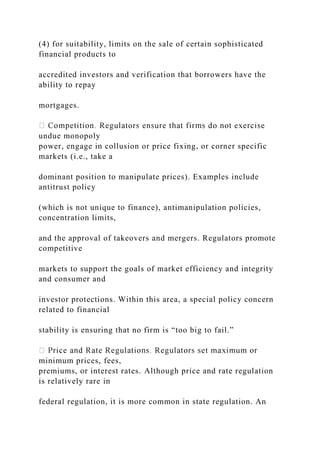

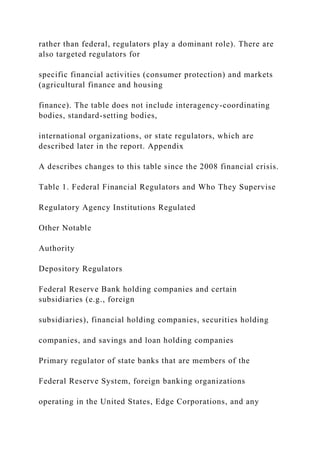

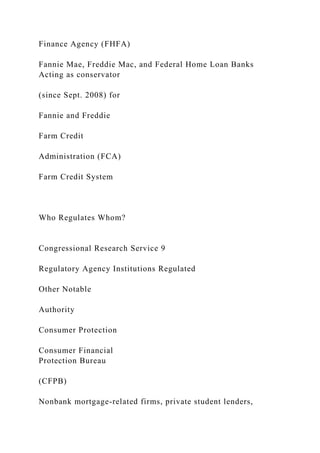

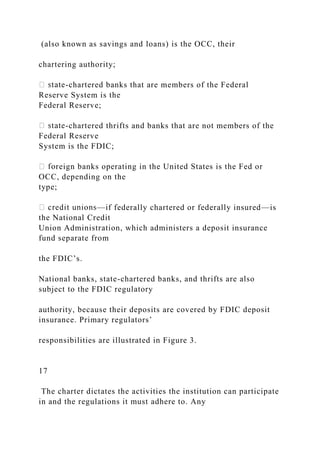

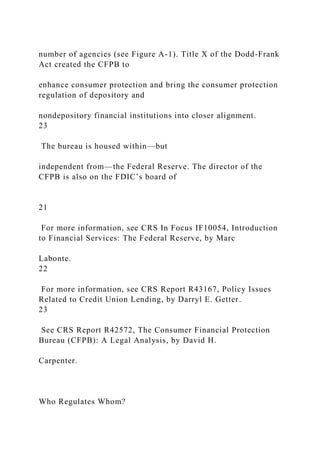

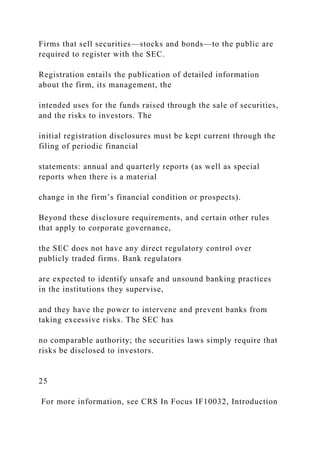

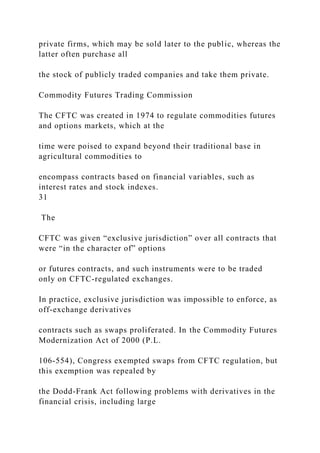

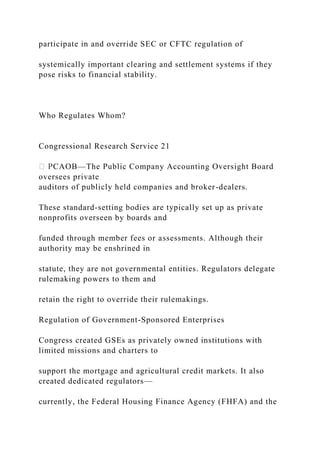

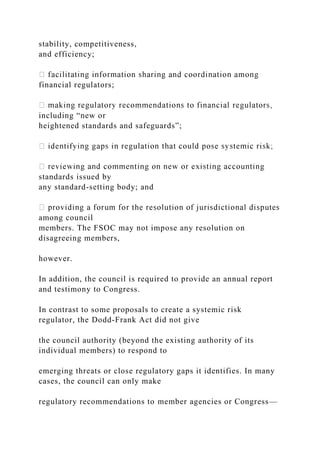

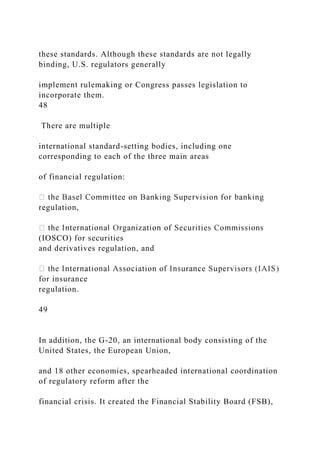

![Specialist in Agricultural

Policy

7-9664 [email protected] Farm credit

David

Perkins

Analyst in Macroeconomic

Policy

7-6626 [email protected] Banking

Gary

Shorter

Specialist in Financial

Economics

7-7772 [email protected] Securities

Baird Webel Specialist in Financial

Economics

7-0652 [email protected] Insurance

Eric Weiss Specialist in Financial

Economics](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assetandliabilitymanagementfin6102ferriterspring2018-221015032421-8db7f4ac/85/Asset-and-Liability-ManagementFin6102Ferriter-Spring-2018-docx-149-320.jpg)

![7-6209 [email protected] Housing finance

Martin

Weiss

Specialist in International

Trade and Finance

7-5407 [email protected] International finance

Author Contact Information

Marc Labonte

Specialist in Macroeconomic Policy

[email protected], 7-0640

Acknowledgments

This report was originally authored by former CRS Specialists

Mark Jickling and Edward Murphy.

mailto:[email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

mailto:[email protected]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assetandliabilitymanagementfin6102ferriterspring2018-221015032421-8db7f4ac/85/Asset-and-Liability-ManagementFin6102Ferriter-Spring-2018-docx-150-320.jpg)

![mailto:[email protected]

Name:

Spring 2019 FIN 6102

Please complete the following problems. Each problem is worth

5 points each. Maximum number of points available is 40.

1. You are looking to purchase a 25 year life insurance policy

for $150,000. The policy will pay annually at the end of the

year. The current market interest rate is 2.5%. What should the

annual payment per year be?

2. You have earned a pension worth $2,000 a month, you think

you will live and additional 15 years. The current prevailing

interest rate is 2% per year. What is the current market value of

your pension?

3. You are attempting to price a 25 year annuity due for your

insurance company. Payments of $3,500 for this annuity due

start at the beginning of each year. The investment team at your

company guarantees a return of 8%. What is the lowest price

your company should offer?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assetandliabilitymanagementfin6102ferriterspring2018-221015032421-8db7f4ac/85/Asset-and-Liability-ManagementFin6102Ferriter-Spring-2018-docx-151-320.jpg)