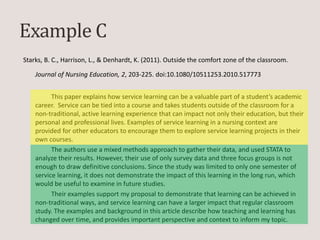

This document outlines steps for creating an annotated bibliography and evaluating academic articles. It discusses finding relevant sources, taking notes, citing sources, writing critiques, and reviewing critiques. It provides examples of article critiques and evaluates strengths and limitations. The document aims to help participants learn a strategic approach to critiquing articles and understanding what makes for a strong evaluation.