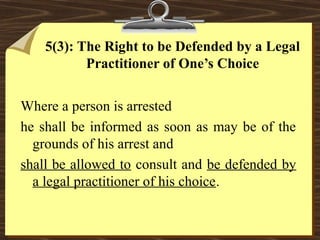

This document summarizes the rights of an arrested person under Article 5(3) and (4) of the Malaysian constitution. It discusses the three main rights: 1) the right to be informed of the grounds for arrest, 2) the right to consult a legal practitioner, and 3) the right to be defended by a legal practitioner of one's choice. It examines Malaysian case law that has interpreted and established limitations on these rights, such as allowing a reasonable delay before access to a lawyer to avoid interfering with police investigations. The document also discusses exceptions to these rights for enemy aliens under certain security laws.

![Arrest

Shabaan & Ors v. Chong Fook Kam & Anor [1969] 1 LNS

170.

Lord Devlin :

"An arrest occurs when a police officer states in terms that he

is arresting or when he uses force to restrain the individual

concerned.

It occurs also when by words or conduct he makes it clear

that he will, if necessary, use force to prevent the

individual from going where he may want to go.

It does not occur when he stops an individual to make

inquiries."](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-2-320.jpg)

![5(3): The right to be informed of the

grounds of arrest

The arrested person may be informed

orally of the grounds of his arrest.

Re P.E. Long @ Jimmy [1976] 2 MLJ 133](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-12-320.jpg)

![5(3): The right to be informed

‘Where a person is arrested he shall be

informed as soon as may be of the

grounds of his arrest.’

Abdul Rahman v Tan Jo Koh

[1968] 1 MLJ 205

cited

Christie v Leachinsky [1947] AC 573.

Immediately](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-13-320.jpg)

![5(3): The right to be informed

Aminah v Superintendent of Prison,

Pengkalan Chepa, Kelantan [1968] 1

MLJ 92

cited

Tarapade v State of West Bengal [1959]

SCR 212

" ...the words 'as soon as may be' …

means as nearly as is reasonable in

the circumstances of the particular

case".](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-14-320.jpg)

![5(3): The right to be informed

The rights stated in article 5 (3) should be applied

whenever a person is arrested under any law.

The Emergency (Public Order and Prevention of

Crime) Ordinance, 1969

IGP v Lee Kim Hoong [1979] 2 MLJ 291

KAM TECK SOON V TIMBALAN MENTERI

DALAM NEGERI MALAYSIA & ORS AND

OTHER APPEALS [2003] 1 MLJ 321](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-15-320.jpg)

![Existing Law

Assa Singh v MB of Johore

[1969] 2 MLJ 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-16-320.jpg)

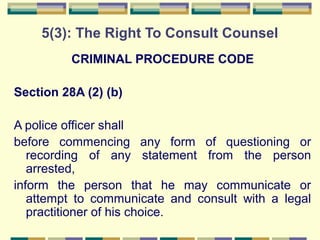

![5(3): The Right To Consult Counsel

Ramli bin Salleh [1973] 1 MLJ 54

Syed Agil Barakbah J.:

(1) The right of begins right from the day of his arrest even

though police investigation has not yet been completed.

(2) The right should be subject to certain legitimate

restrictions which necessarily arise in the course of police

investigation, the main object being be ensure a proper and

speedy trial in the Court of law.

(3) Such restrictions may relate to time and convenience of

both the police and the person seeking the interview and

should not be subject to any abuse by either party.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-20-320.jpg)

![Ramli bin Salleh [1973] 1 MLJ 54

Held:

The action of the respondent in this case in

restricting the learned counsel's application to

interview his client on the expiry of the detention

period is unreasonable.

It should therefore be understood that the police

must not in any way delay or obstruct such

interviews on arbitrary or fanciful grounds with a

view to deprive the accused of his fundamental

right.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-21-320.jpg)

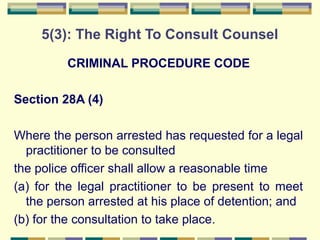

![5(3): The Right To Consult Counsel

Ooi Ah Phua [1975] 2 MLJ 198

Suffian LP

“ the right…begins from the moment of arrest

but…cannot be exercised immediately after

arrest.

A balance has to be struck between

the right of the arrested person to consult his

lawyer on the one hand and

on the other the duty of the police to protect the

public from wrong-doers by apprehending

them and collecting whatever evidence exists

against them.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-22-320.jpg)

![Ooi Ah Phua v Officer in Charge, Criminal

Investigations, Kedah/Perlis

[1975] 2 MLJ 198

The Federal Court held that

a delay of ten days

between arrest and access to counsel

was lawful.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-23-320.jpg)

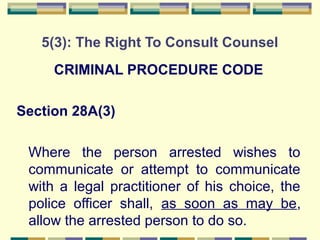

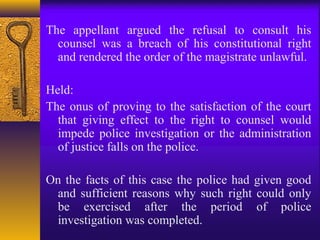

![Hashim bin Saud [1977] 2 MLJ 116

The appellant had been arrested on suspicion of

being involved in the theft of an electric generator.

After being questioned he was produced before a

magistrate and ordered to be detained under

section 117 of the CPC.

An application was made for a lawyer to visit the

appellant but this was not immediately granted.

He could only see the appellant on a subsequent date

when the investigations were expected to be

completed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-24-320.jpg)

![5(3): The Right To Consult Counsel

The effect of unlawful denial of the right under article 5 (3).

Ooi Ah Phua

[1975] 2 MLJ 198

NASHARUDDIN BIN NASIR V KERAJAAN MALAYSIA

& ORS

[2002] 6 MLJ 65

Mohamad Ezam bin Mohd Noor v Ketua Polis Negara &

other appeals

[2002] 4 MLJ 449](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-30-320.jpg)

![Re. GG Ponnambalam [1969] 2

MLJ 263

It is argued that the article gave the accused

person the right to be defended by a legal

practitioner of his choice.

The learned CJ rejected the argument.

Until the person is admitted, no qualified person

is a legal practitioner under Art. 5.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-32-320.jpg)

![D’Cruz v AG, Malaysia & Anor

[1971] 2 MLJ 130

The right given under Art. 5 cannot be read as

extending to any legal practitioner anywhere in the

world regardless whether or not he is qualified to

practise here.

The right given to the arrested person in the article

must be limited to the choice of legal practitioners

who are qualified to practise under our law.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-33-320.jpg)

![CHERIE BOOTH QC V. ATTORNEY

GENERAL, MALAYSIA & ORS [2006] 4

CLJ 224

PEGUAM NEGARA & ORS v. GEOFFREY

ROBERTSON [2002] 2 CLJ 493](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-35-320.jpg)

![5(3): Legal Practitioner of One’s Choice

Mohamed bin Abdullah v PP [1980] 2 MLJ 201

The question is whether the Court could proceed with

the trial in the absence of Counsel and if not whether

the trial was a nullity.

Held:

It is wrong to say that a litigant is entitled to be

represented by the Counsel of his choice.

The true statement is that he is entitled to be

represented by the Counsel of his choice if that

Counsel is willing and able to represent him.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-36-320.jpg)

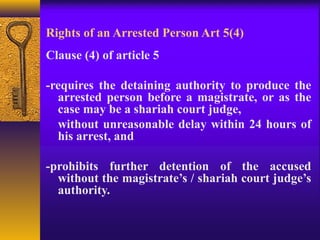

![5(4) : The right to be Produced Before a Magistrate

Aminah v Superintendent of Pudu Prison,

Pengkalan Chepa, Kelantan [1968] 1

MLJ 92

“Article 5 clearly meant to apply to arrests

under any law whatsoever in this

country”.

The Federal Court agreed to “read into” the

RRE Article 5 (3) and (4) as permitted

by article 162(6)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-40-320.jpg)

![5(4) : The right to be Produced Before a Magistrate

The position later changed after the clause

was amended.

Para 2 of (4) in Article 5.

Loh Kooi Choon v Govt of Malaysia [1977] 2

MLJ 187](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-41-320.jpg)

![5(4) : The right to be Produced Before a Magistrate

Exception

Chong Kim Loy v The Menteri Dalam Negeri,

Malaysia [1989] 3 MLJ 121

He was arrested under S. 3 of the Dangerous Drugs (Special

Preventive Measures) Act 1965 and later detained under

the law.

It was argued that there had been a contravention of Article

5(4) of the Constitution as the applicant had not been

produced before a Magistrate within 24 hours after his

arrest and detention at the police station.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/article5-rightsunderarticle534-141002182008-phpapp02/85/Article-5-rights-under-article-5-3-4-42-320.jpg)