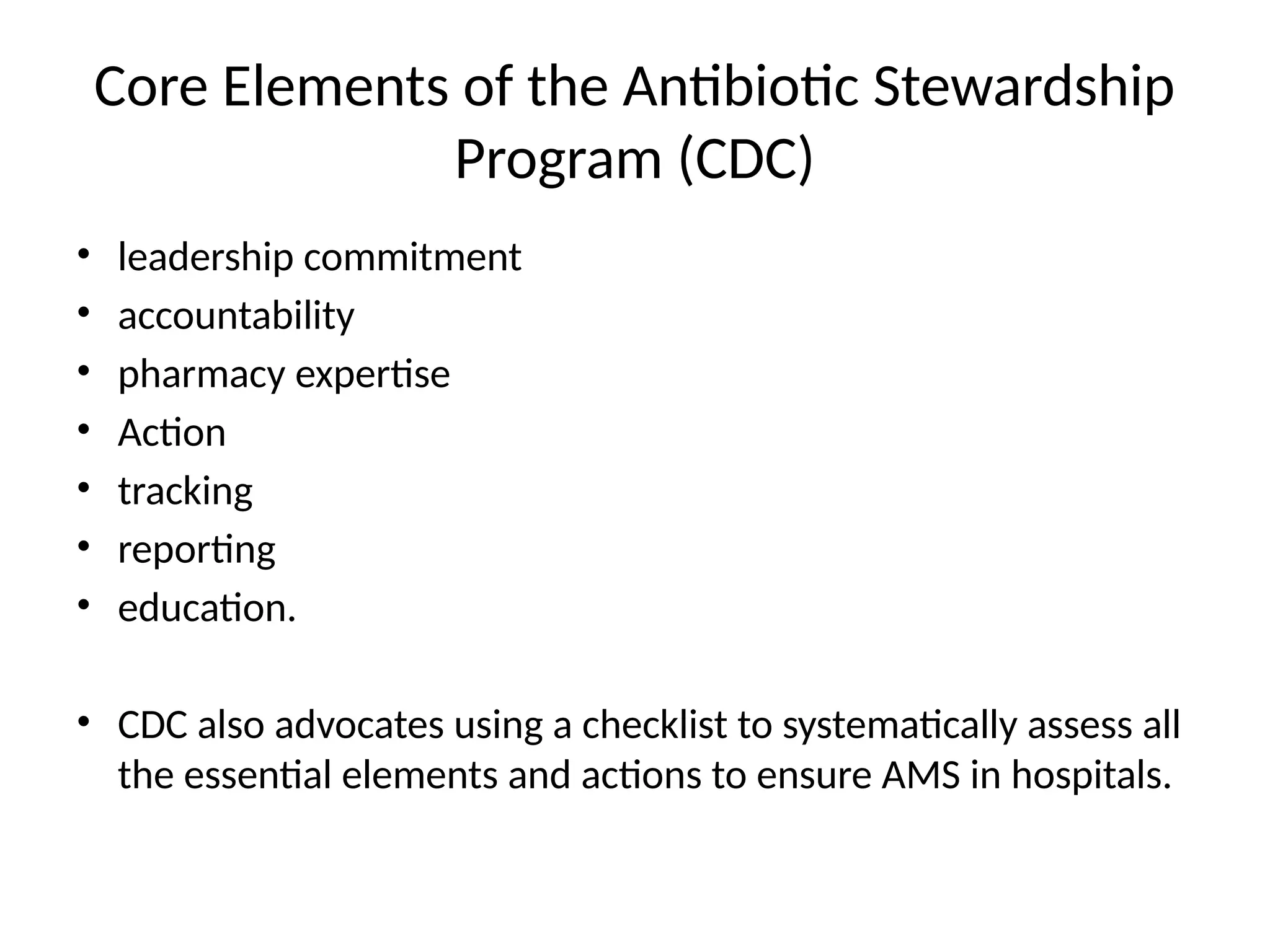

The document outlines antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) as a coordinated approach to optimize antimicrobial use, particularly in neonatal care, to combat rising antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and improve patient outcomes. It highlights the challenges in diagnosing and managing infections in neonates, along with the necessity for an effective AMS program to mitigate the risks associated with antibiotic use. Key strategies for implementing AMS and measuring its success are discussed, emphasizing the collaborative role of healthcare professionals in optimizing antimicrobial therapy.