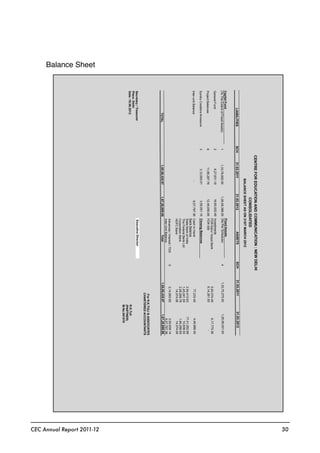

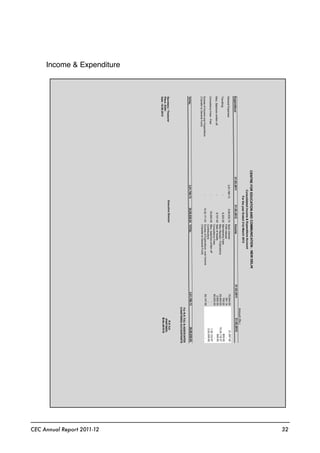

The document is the 2011-12 annual report of the Centre for Education and Communication (CEC). It discusses CEC's work over the past year on issues related to labour rights and livelihoods, with a focus on marginalized groups. Some of the key areas covered include sustainable livelihoods for small tea growers, changing labour dynamics in global supply chains, child labour issues, labour rights in special economic zones, taxation and social security policies, and the Maruti Suzuki workers' struggle. The report was prepared by Pallavi Mansingh and Divya Devan. It includes the executive director's note, details of various projects, financial information, and the governing board members.