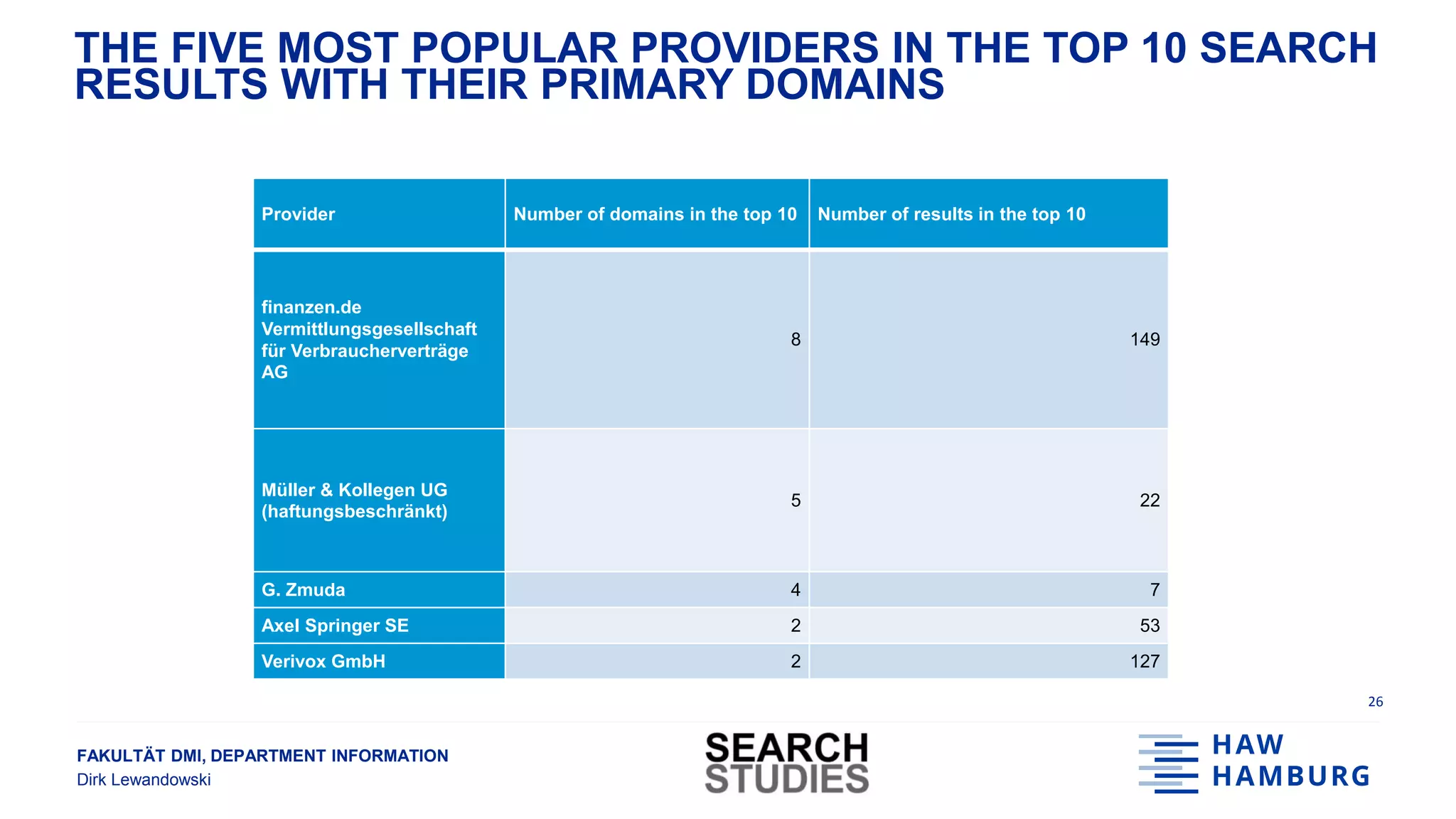

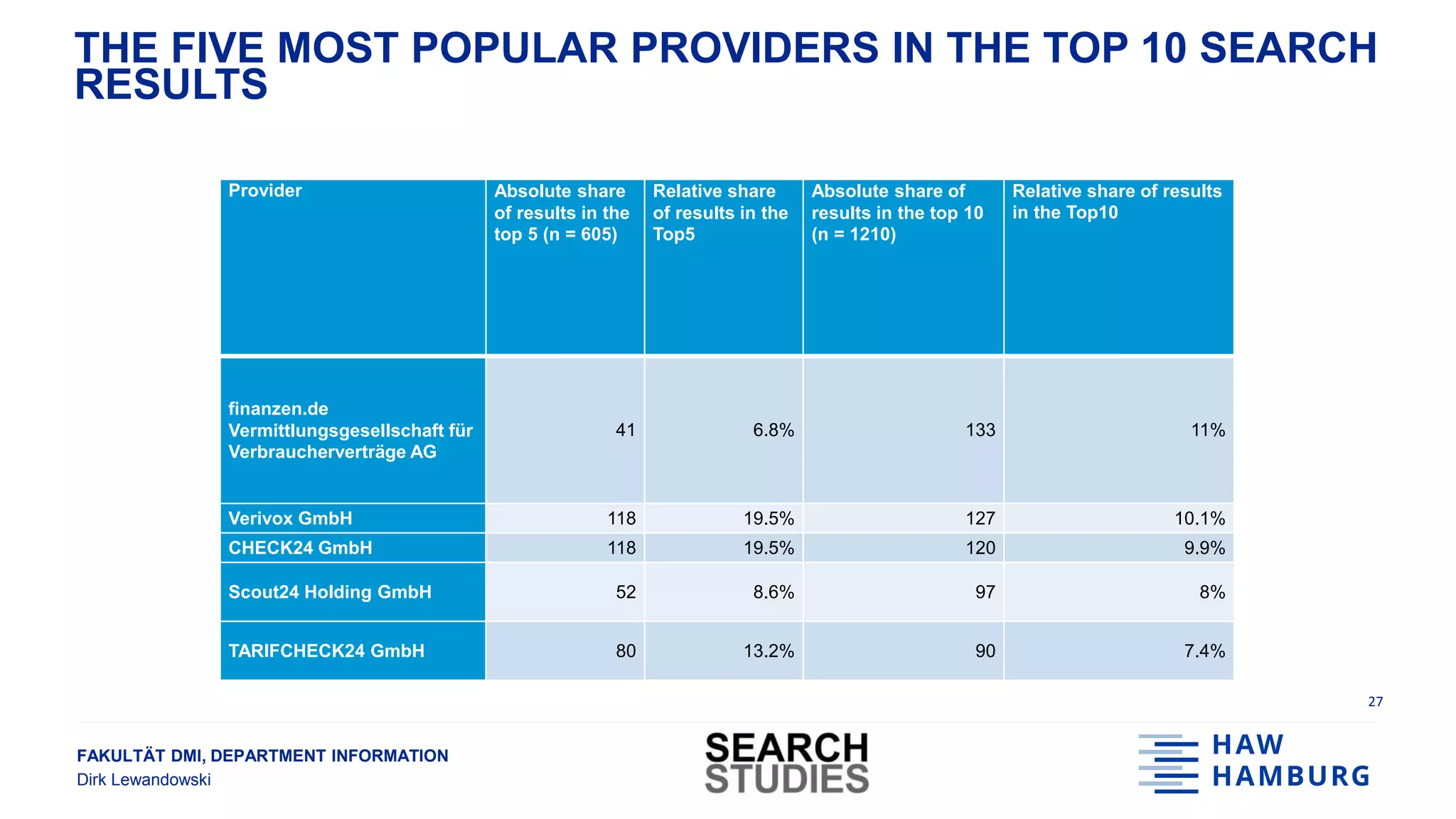

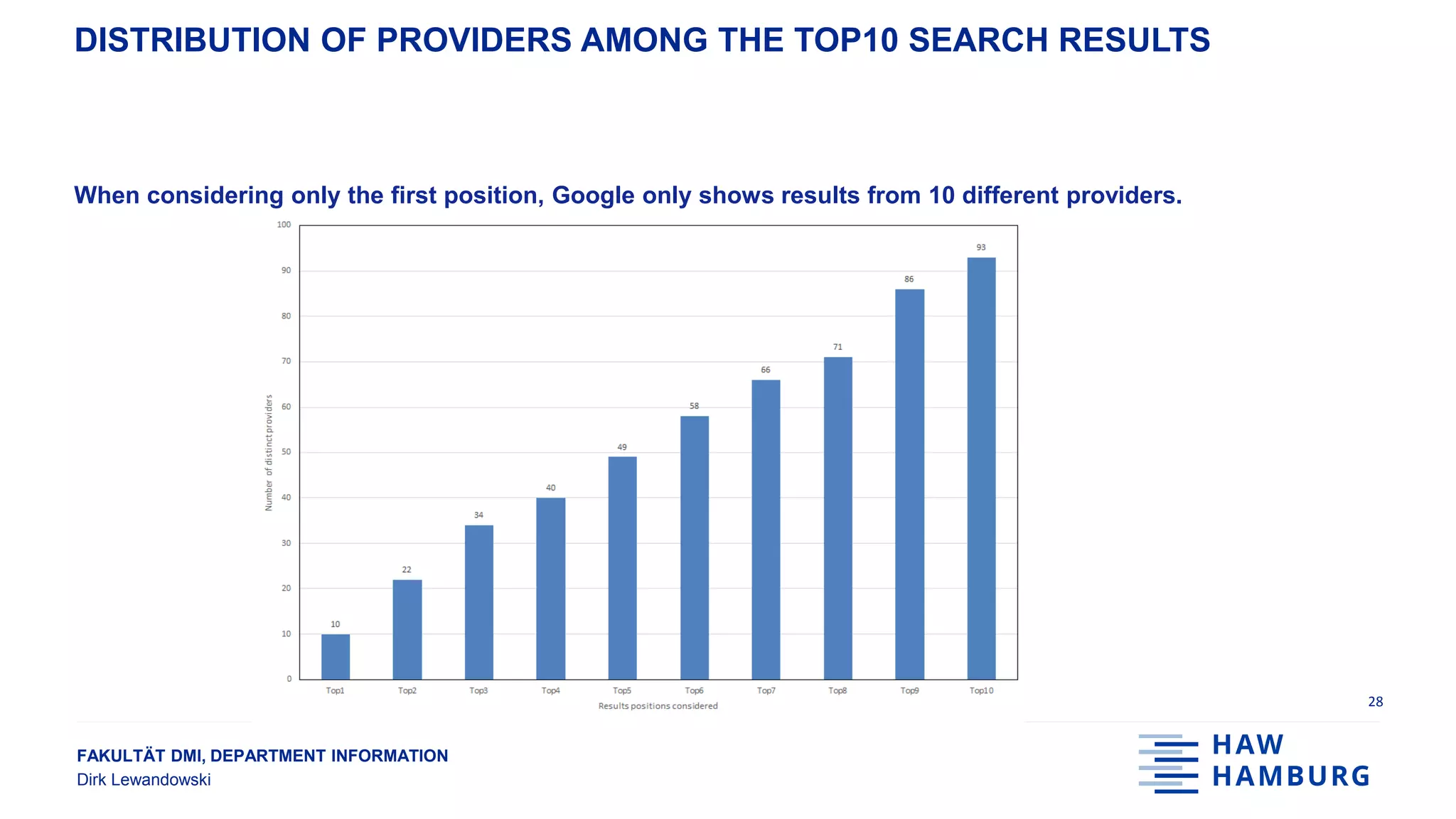

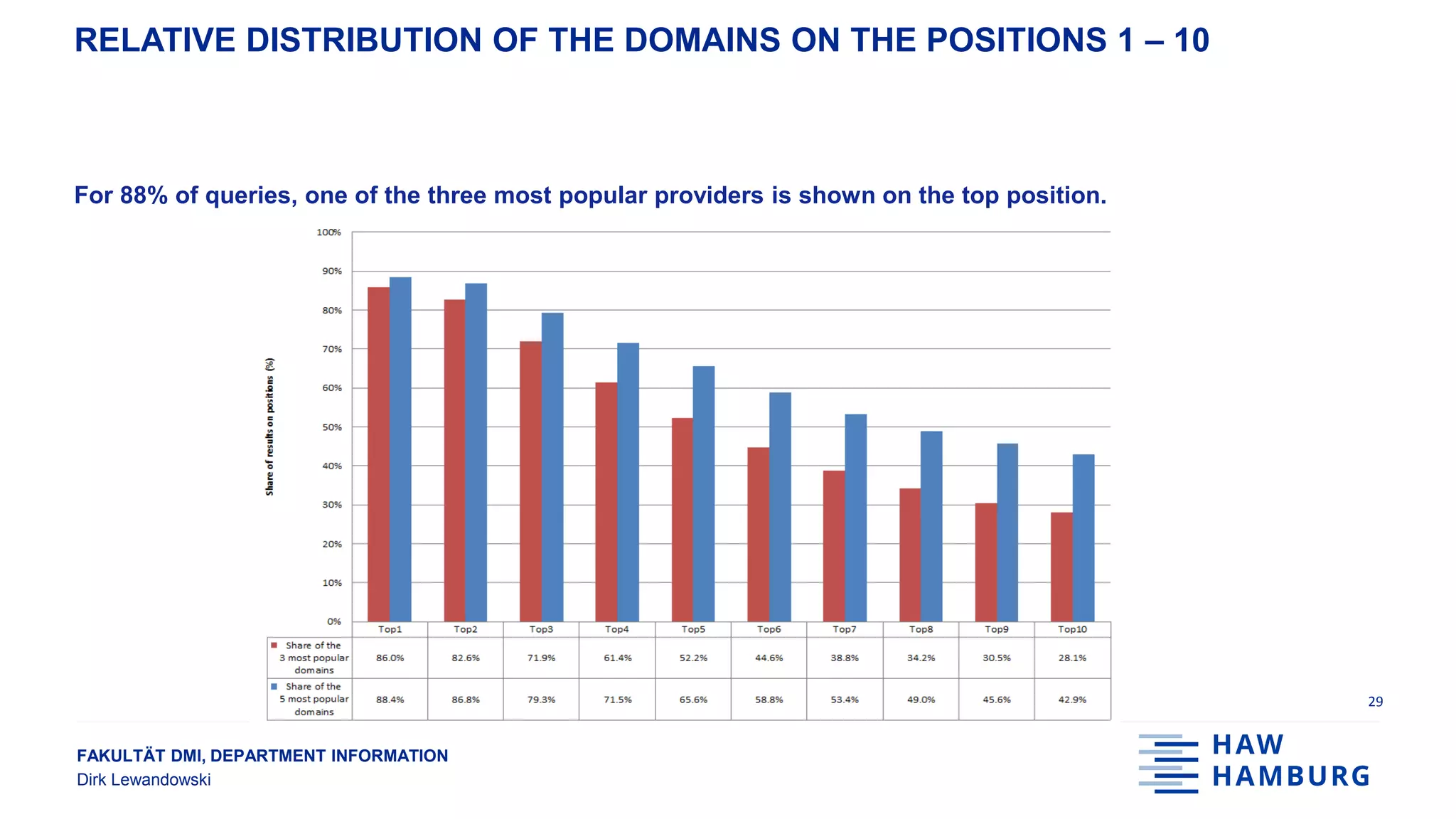

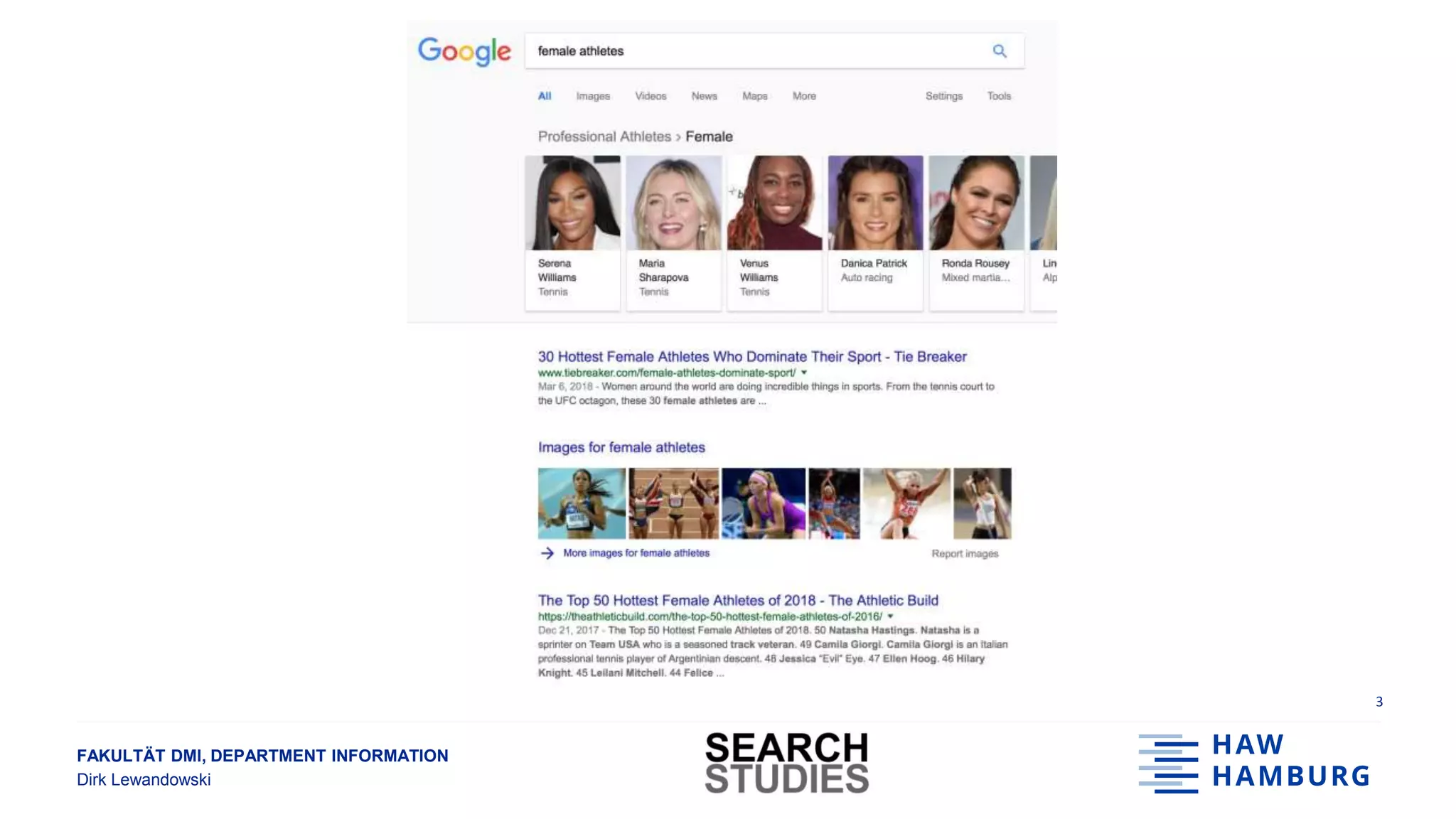

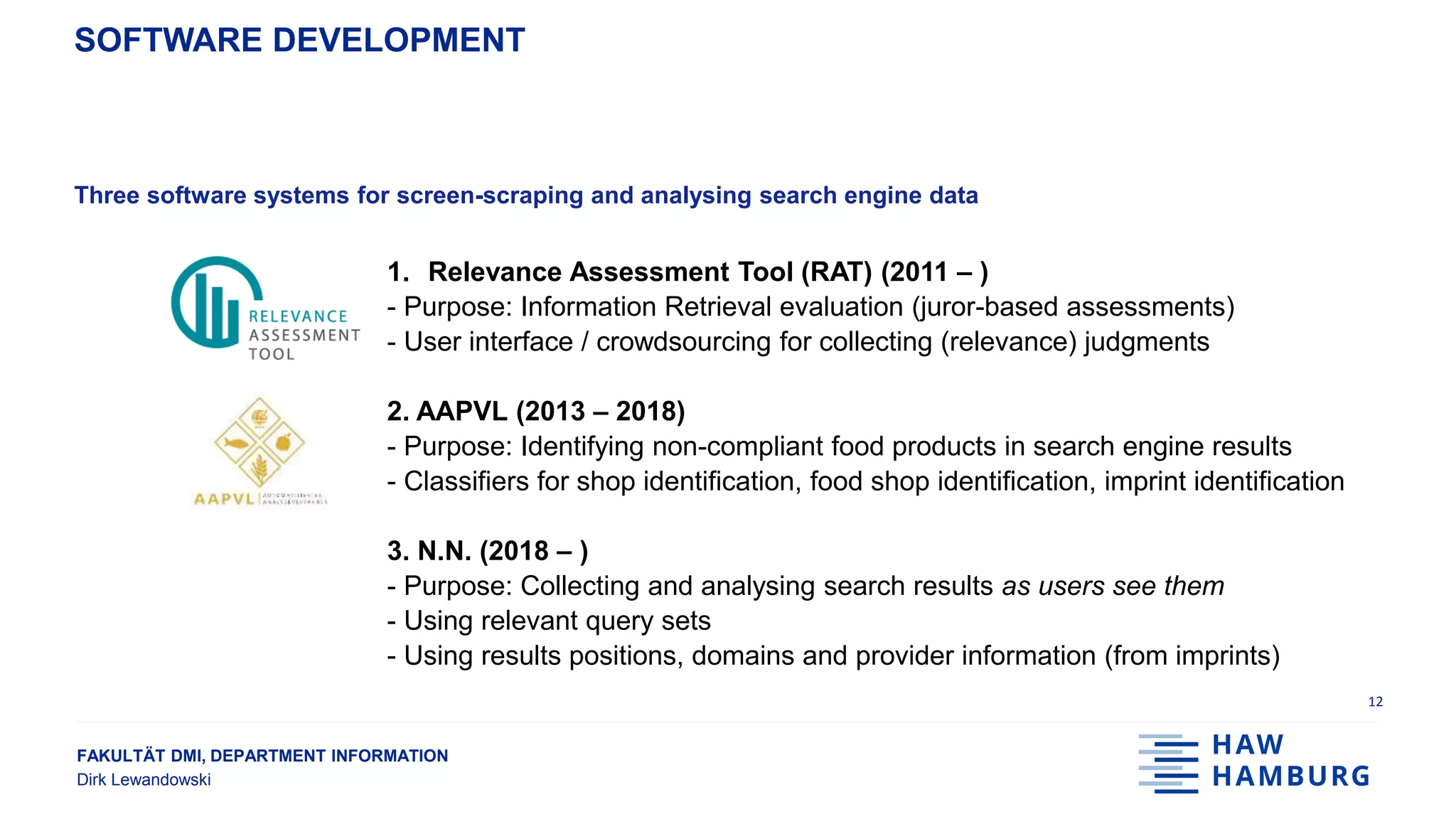

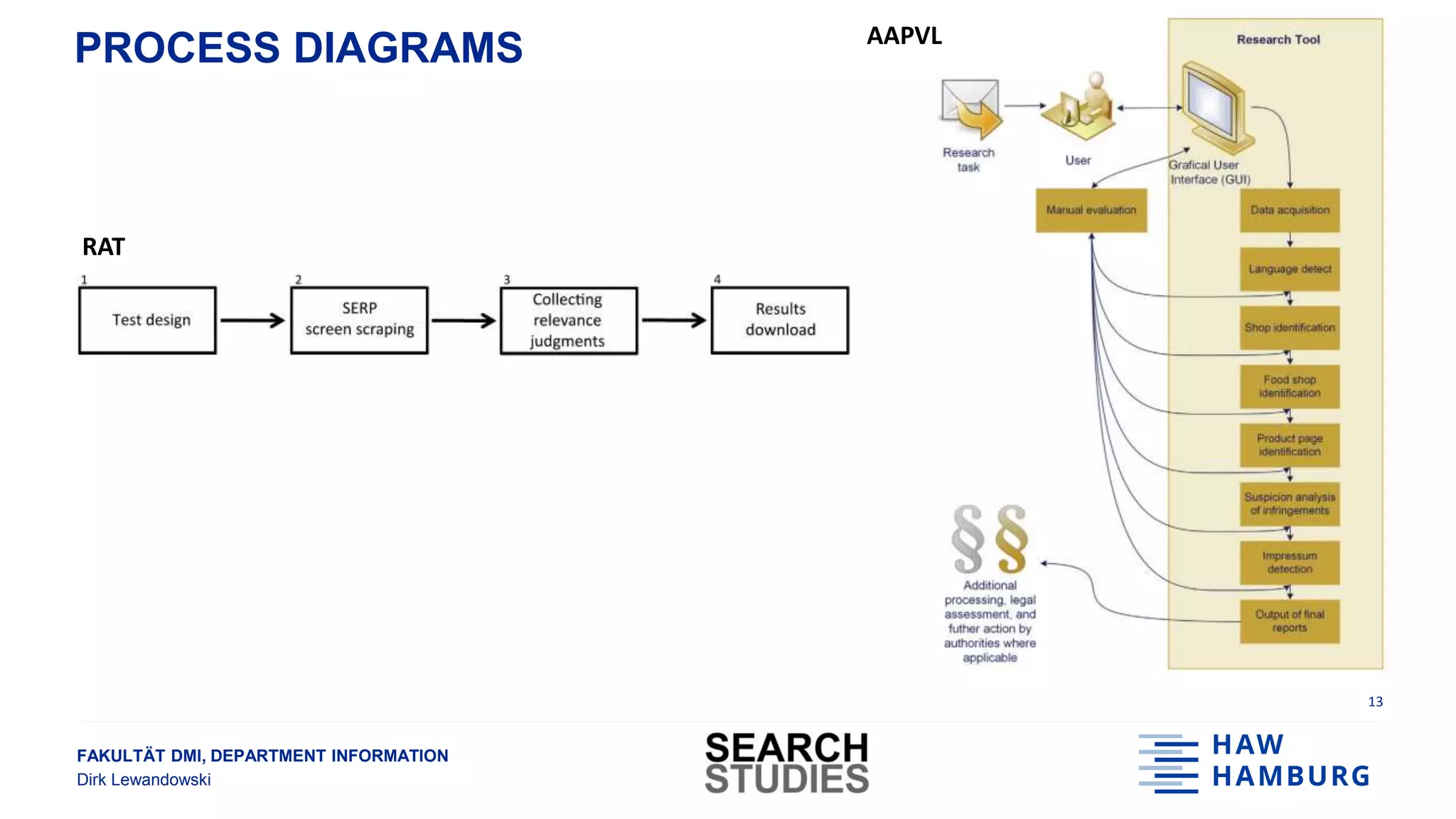

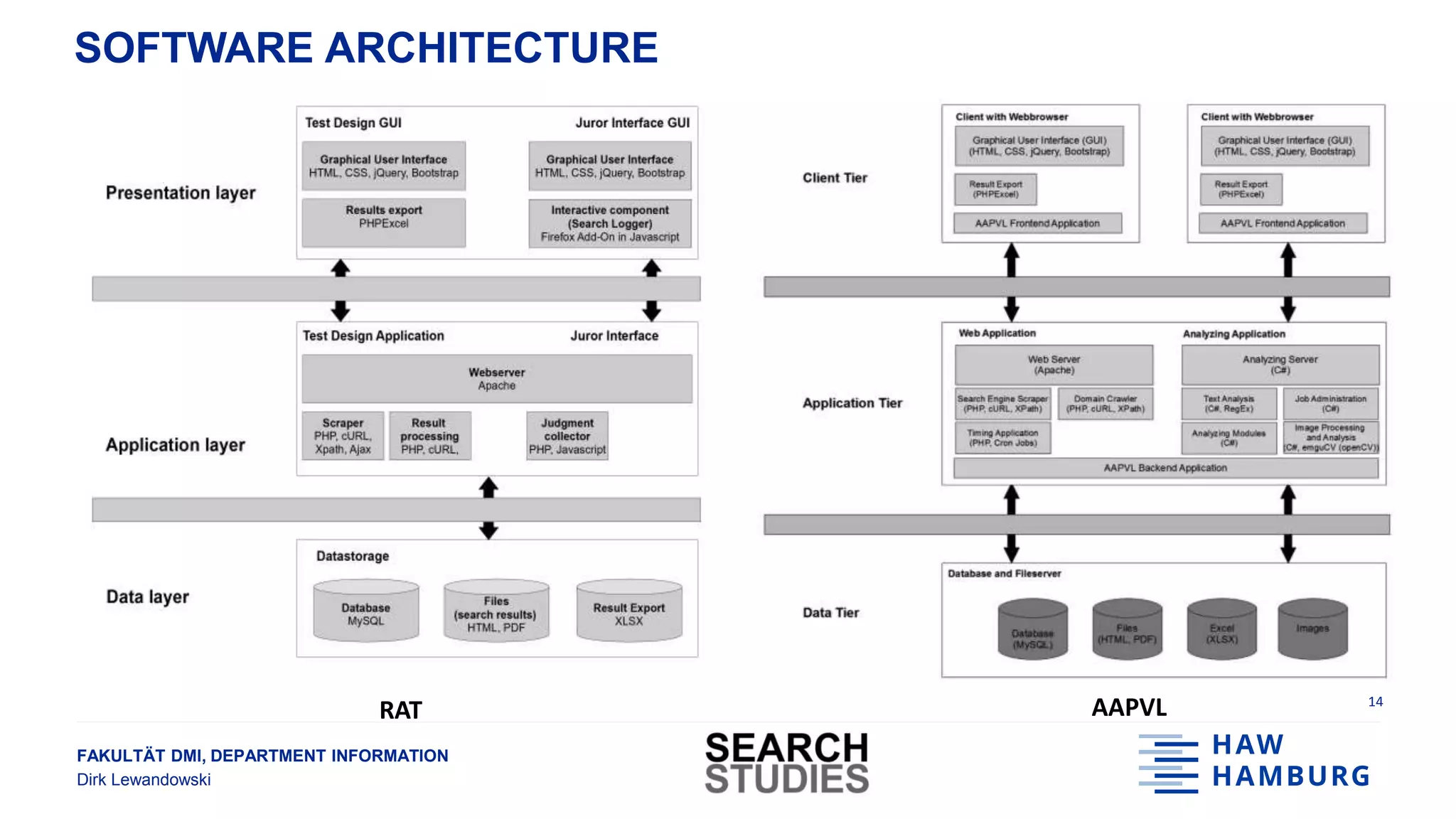

This document summarizes a presentation on analyzing search engine data for socially relevant topics. It discusses collecting search results data at scale by automatically querying search engines and scraping results pages. A case study on insurance comparisons is presented where over 20,000 search results were analyzed for 121 queries. The results showed that a small number of domains and providers dominated the top search positions. Limitations and future work are also outlined.

![FAKULTÄT DMI, DEPARTMENT INFORMATION

Dirk Lewandowski

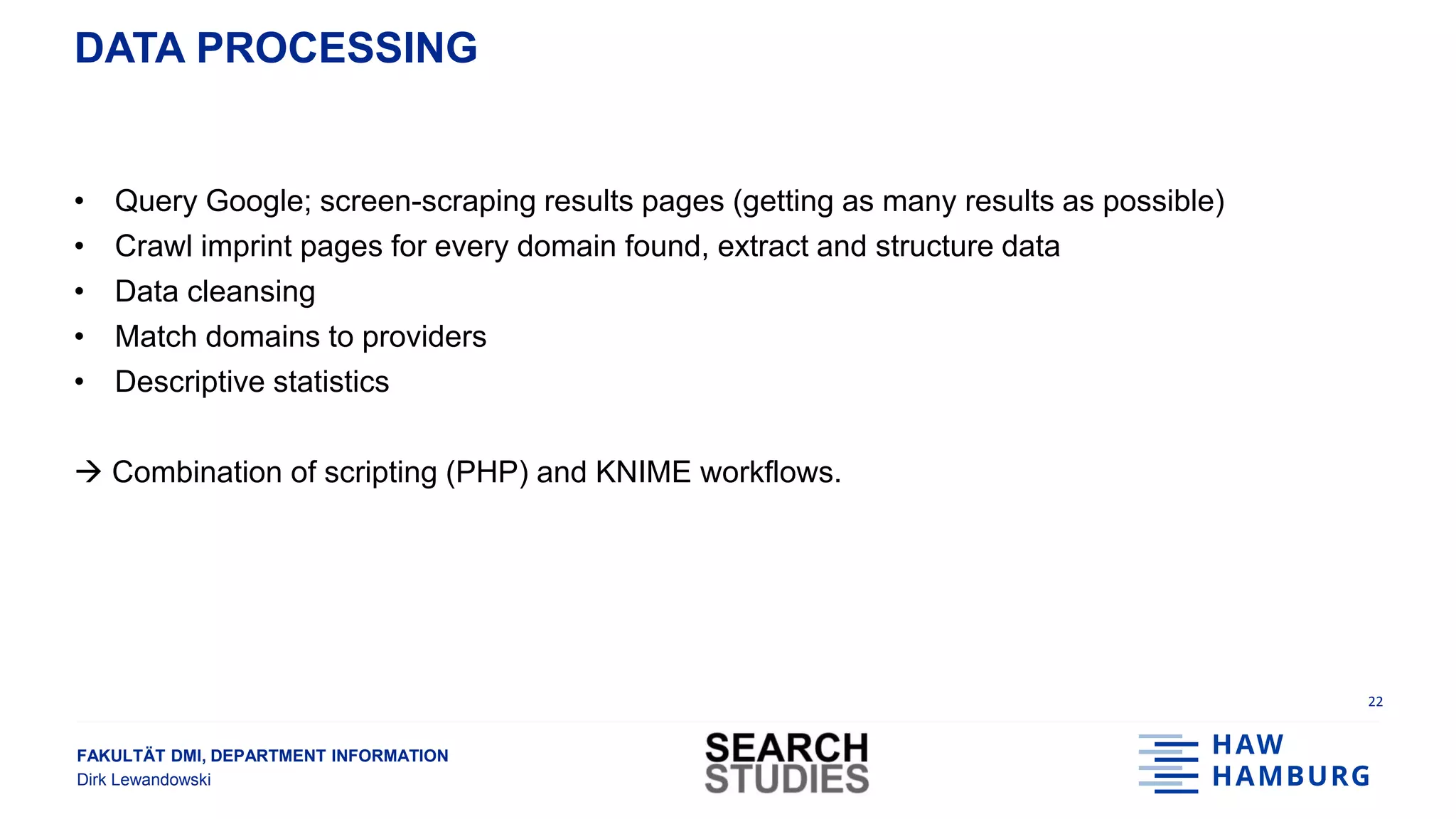

DATA SET

• Number of queries: 121

• Number of search results: 22,138

• Results per query: 183 [1, 298]

• Number of different domains: 3,278

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20180919gesislewandowski-180928131610/75/Analysing-search-engine-data-on-socially-relevant-topics-24-2048.jpg)

![FAKULTÄT DMI, DEPARTMENT INFORMATION

Dirk Lewandowski

RESULTS SUMMARY

25

● 116 different domains in top 10 results [10; 1210]

● 93 different providers in top 10 results, i.e., some providers have more than one domain

● The 5 most popular providers account for 47% of top 10 results (and 67% of top 5 results)

Two thirds of top 5 results are from only five different providers](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20180919gesislewandowski-180928131610/75/Analysing-search-engine-data-on-socially-relevant-topics-26-2048.jpg)