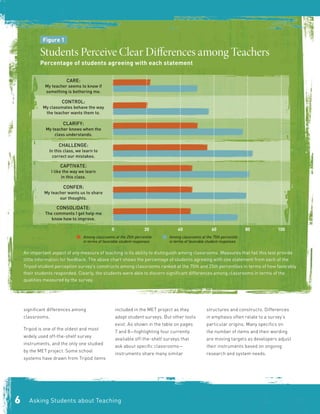

The document discusses the Measures of Effective Teaching (MET) project's report that examines the use of student perception surveys in evaluating teaching effectiveness and providing feedback to educators. It outlines the importance of designing surveys to accurately capture student experiences and emphasizes the need for reliable, valid instruments while addressing the challenges related to implementation. The report highlights the benefits of these surveys, including their predictive validity for student outcomes, and suggests strategies for effectively integrating them into teacher evaluation systems.