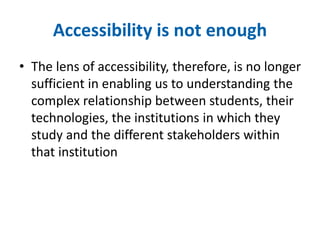

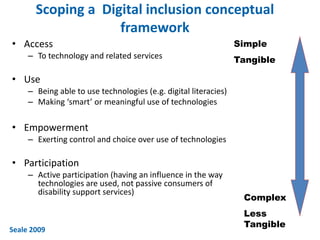

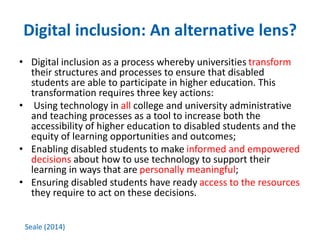

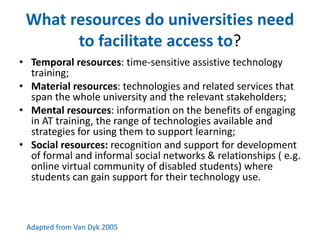

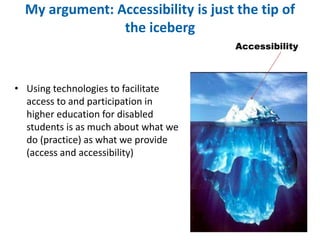

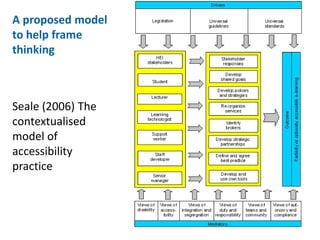

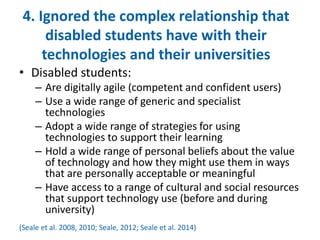

This document summarizes a keynote presentation about universities' role in promoting inclusion of disabled students through technology. The presentation argues that accessibility is not enough, and digital inclusion is a better framework. It acknowledges that disabled students have complex relationships with technologies, use them in many ways, and universities must consider diverse stakeholders and practices to fully include disabled students. A digital inclusion approach transforms university structures and processes to ensure disabled students can participate in higher education through meaningful technology use and access to necessary resources.

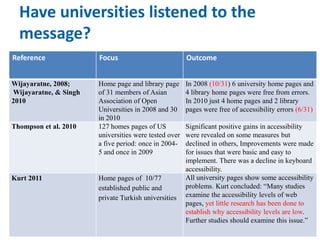

![Example: Beliefs about technology

stigmatising disabled students

Nick: I wouldn't use voice dictation software in public. I'd feel to

self-conscious.

Reena: I have to say that if I’d got that technology, I would use it

at home. I wouldn’t use it in the lab. […]But with technology, I

still think there’s a stigma to it. If I did have assistive

technology I would use it on my home computer. There’s no

way I would use a lot of it in the lab because I wouldn’t want

that stigma on me like that thing – which is bad, but it’s how

people are.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icits2014keynotejaneseale-140917162729-phpapp01/85/Accessibility-is-not-enough-26-320.jpg)

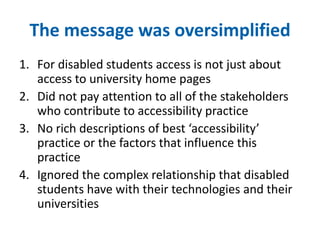

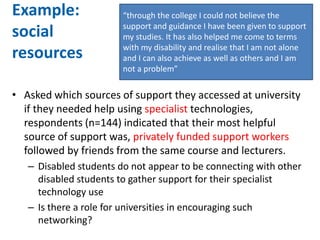

![Example: difficulties engaging in AT

training

Factors Example

Flexibility It was difficult because he had quite a lot that he had to do. And with

being a part-time student they don’t necessarily understand that you’re

working [..] he would want mornings and I couldn’t possibly take time

off work, he can’t come in the evenings. It was just untidy and by the

time I'd see him again in a months' time, well I’d completely forgotten

what he taught me, so it didn’t work, it just didn’t work.[22]

Timeliness The lengthiness of the DSA process made me feel a little behind so

this should be addressed. Maybe identified prior to starting so the

process can be underway before lectures start. Also then I could have

learnt the technology before sessions start so I am ready to go.[17]

Duration Whereas the guys who installed it a. they were very technology

minded as well but they also did it in four-hour blocks and it’s like, by

the end of two hours, I’ve taken in enough and everything else went

out of my head.[7]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icits2014keynotejaneseale-140917162729-phpapp01/85/Accessibility-is-not-enough-31-320.jpg)