The study examined how a parenting class and parental work status affected adjustment to parenthood. Twenty parents attended the parenting class, while eight parents did not (the control group). The class covered various parenting topics. Participants completed surveys on parenting self-efficacy, stress, support, behaviors, and knowledge.

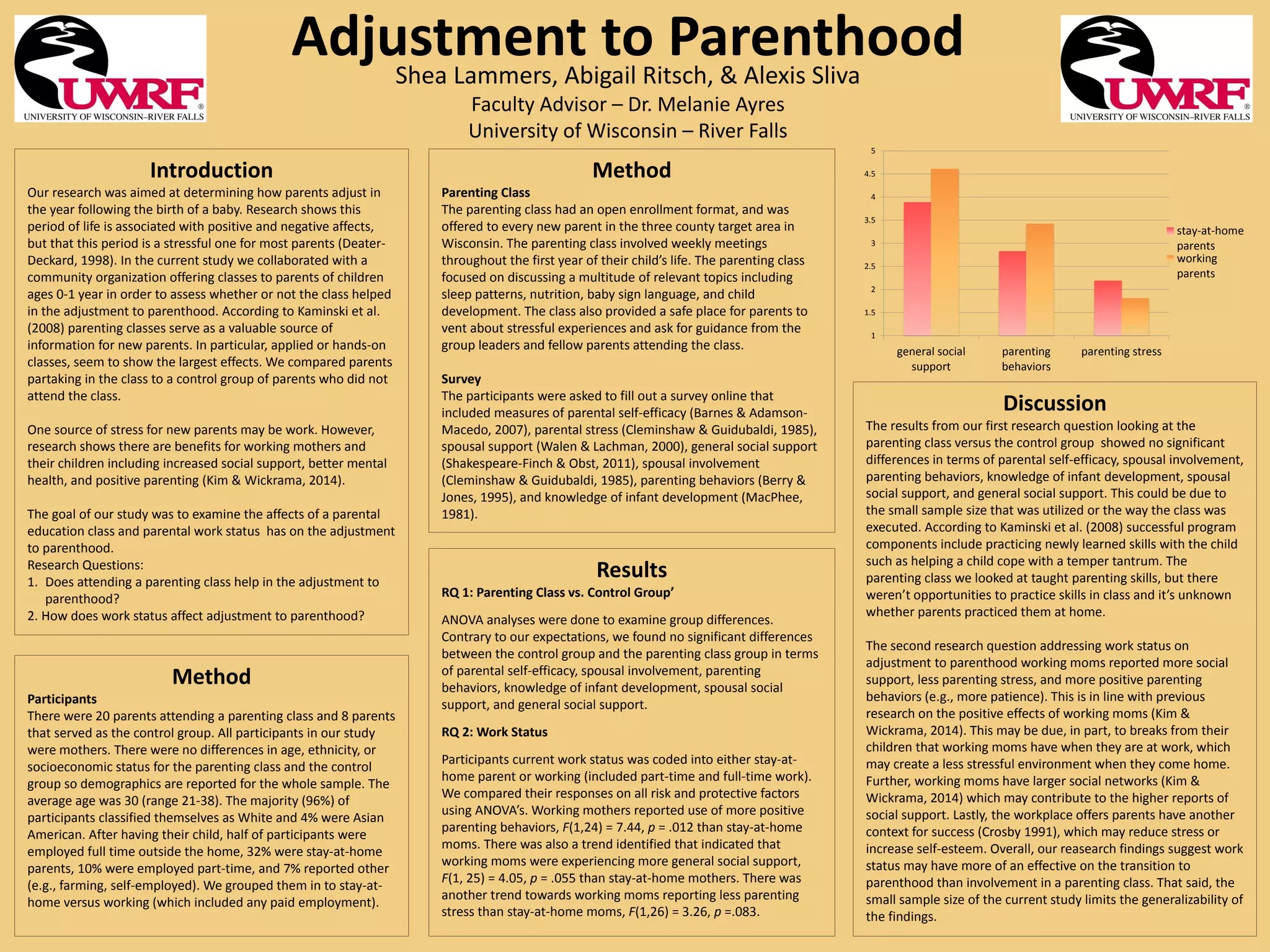

Results found no significant differences between the parenting class and control groups on adjustment factors. However, working mothers reported more positive parenting behaviors, greater social support, and less parenting stress than stay-at-home mothers. This suggests work status may impact adjustment to parenthood more than a parenting class, though sample size was small.