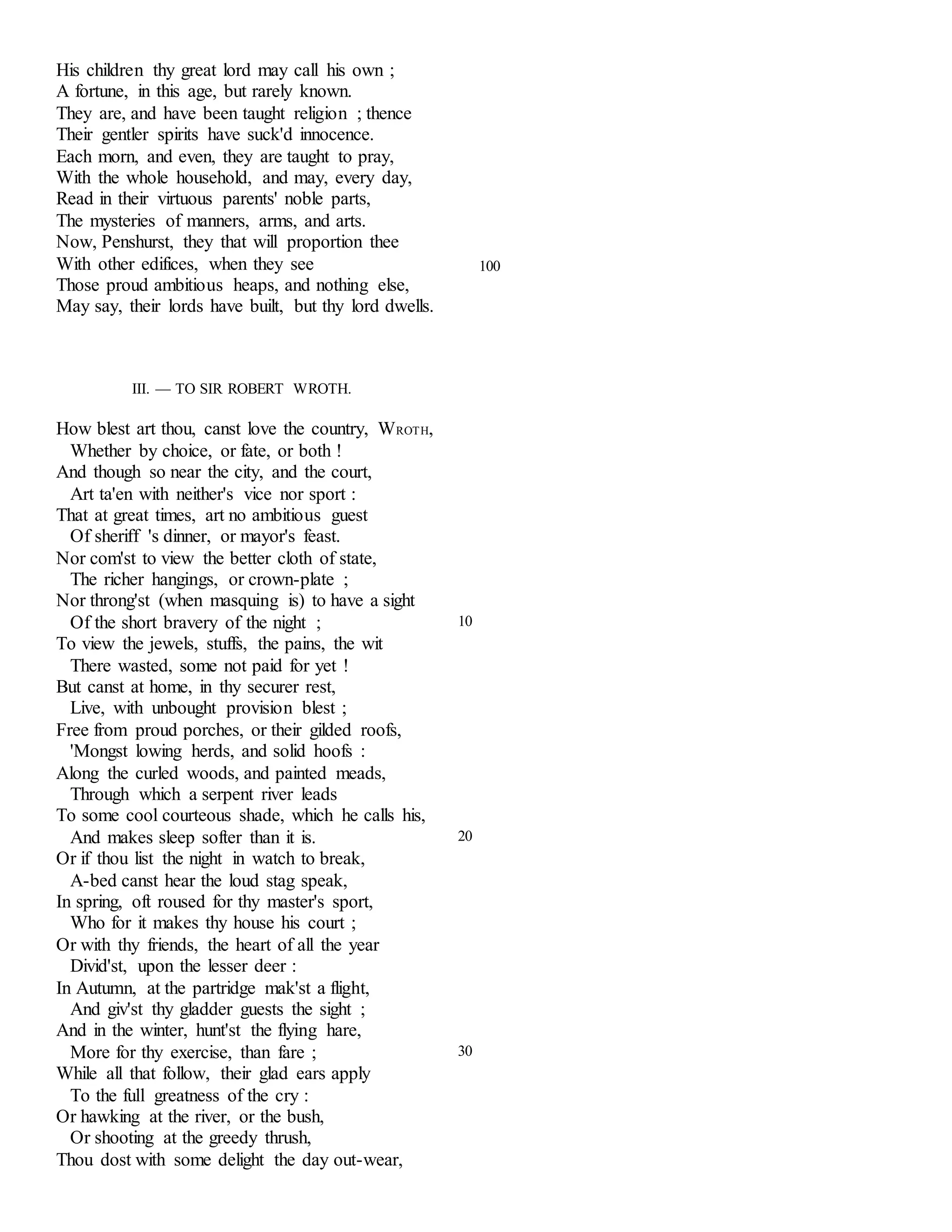

- The poem "To Celia" expresses a man's deep love and devotion for a woman named Celia through the use of metaphors and symbols.

- He compares his love for her to drinking wine or Jove's nectar, suggesting it intoxicates and sustains him. When she returns a wreath of roses he gave her, it shows she does not return his feelings.

- However, the man remains hopeful and persistent in his love, promising it will continue to grow like the roses and always be tied to her.

![this is a good poem i like it but not so much on the part when she sends him back the flowers she should of

kept them i would if i was her;]

by:melissa aka molly dolly

this is a good poem i like it but not so much on the part when she sends him back the flowers she should of

kept them i would if i was her;]

by:melissa aka molly dolly

I see this poem in a different sense. I do not see it as romantic or compassionate but slightly psychotic. He

talks about committing to her, and yet he has only just set eyes upon her across the room. She sends the

flower back, relaying the fact that she is not interested and yet all he notices is it now has her breath on it. She

may not have even intended to breathe on it but he looks past this and sees it as a clear sign his feelings are

reciprocated back to him from her. As the courtly tradition she is probably already married which could back

up why she sent the gift back. When i read this poem i just get the image of a man trying to hold the attention

of a woman he is attracted to across the room, and she is politely declining his offers. He never states anything

she does back to him. I just fail to see the romantic side to it.

This is a very sweet poem and it is my favourite too

In this poenm speaker is expressing his deep feelings and love for Celia,He wants the faithful love from his

frind tht's why he said" Drink to me with thine eyes and i will pledge with mine"He does not want to exchange

his glass of wine with jove's nector cup i.e the roman god (Jupitor) Jove's nector or the drink of god,Speaker

would give up the drink of the god for a drink from a cup which her lips merely have touched, but it’s not wine

he searches for. He simply wishes for his lovers love.

Then He sends her “a rosy wreath.He send them to devote her that they would not withered their and

remains fresh, but she send it back to him after breathing and since than roses are giving the smell of his

friend.Such a nice poem.charming tribute of love that age of love poems.

speaker has deep and compelling love for his love celia that he is willing to give up anything in particular in

exchange for Celia's compassion and love

This is a very sweet poem and it is my favourite too

In this poenm speaker is expressing his deep feelings and love for Celia,He wants the faithful love from his

frind tht's why he said" Drink to me with thine eyes and i will pledge with mine"He does not want to exchange

his glass of wine with jove's nector cup i.e the roman god (Jupitor) Jove's nector or the drink of god,Speaker

would give up the drink of the god for a drink from a cup which her lips merely have touched, but it’s not wine

he searches for. He simply wishes for his lovers love.

Then He sends her “a rosy wreath.He send them to devote her that they would not withered their and

remains fresh, but she send it back to him after breathing and since than roses are giving the smell of his

friend.Such a nice poem.charming tribute of love that age of love poems.

speaker has deep and compelling love for his love celia that he is willing to give up anything in particular in

exchange for Celia's compassion and love

my analysis for this poem is that the speaker has deep and compelling love for Celia that he is willing to give

up anything in particular in exchange for Celia's compassion and love. He had attempted to court her by

sending her roses but unfortunately Celia declines his offer and sent it back to him. But when the roses was

returnde, it no longer smell like it did but now it posess the fragrance and smell of thy beloved Celia. This love](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-4-2048.jpg)

![expressing our emotions. It's like powerful emotions are almost spiritual, and the soul just doesn't play by the

rules of vocabulary.

That doesn't mean you should give it a shot, though. Go ahead. You know you want to write a poem called "To

Fries with Mayo." But be sure to check out "To Celia" first. You might learn a thing or two from Ben Jonson on

how to express your passion in words.

Benjamin Sinclair "Ben" Johnson, CM OOnt (born December 30, 1961 in Falmouth, Jamaica), is a former

sprinter from Canada, who enjoyed a high-profile career during most of the 1980s, winning two Olympic

bronze medals and an Olympic gold, which was subsequently rescinded. He set consecutive 100 metres world

records at the 1987 World Championships in Athletics and the 1988 Summer Olympics, but he was disqualified

for doping, losing the Olympic title and both records.

Biography

Career background

Born in Falmouth, Jamaica, Johnson emigrated to Canada in 1976, residing in Scarborough, Ontario.

Johnson met coach Charlie Francis and joined the Scarborough Optimists track and field club, training at York

University. Francis was a Canadian 100 metres sprint champion himself (1970, 1971 and 1973) and a member

of the Canadian team for the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. Francis was also Canada's national sprint

coach for nine years.

Johnson's first international success came when he won two silver medals at the 1982 Commonwealth Games in

Brisbane, Australia. He finished behind Allan Wells of Scotland in the 100 m with a time of 10.05 seconds and

was a member of the Canadian 4x100 m relay team. This success was not repeated at the 1983 World

Championships in Helsinki, where he was eliminated in the semi-finals, finishing 6th with a time of 10.44.

At the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, he reached the 100 m final; after false starting, he won the

bronze medal behind Carl Lewis and Sam Graddy with a time of 10.22. He also won a bronze medal with the

Canadian 4x100 m relay team of Johnson, Tony Sharpe, Desai Williams and Sterling Hinds, who ran a time of

38.70. By the end of the 1984 season, Johnson had established himself as Canada's top sprinter, and on August

22 in Zurich, Switzerland, he bettered Williams' Canadian record of 10.17 by running 10.12.

In 1985, after eight consecutive losses, Johnson finally beat Carl Lewis. Other success against Lewis included

the 1986 Goodwill Games, where Johnson beat Lewis, running 9.95 for first place, against Lewis' third-place

time of 10.06. He broke Houston McTear's seven-year old world record in the 60 metres in 1986, with a time of

6.50 seconds.[1] He also won Commonwealth gold at the 1986 games in Edinburgh, beating Linford Christie for

the 100 m title with a time of 10.07. Johnson also led the Canadian 4x100 m relay team to gold, and won a

bronze in the 200 m.

On April 29, 1987, Johnson was invested as a Member of the Order of Canada. "World record holder for the

indoor 60-meter run, this Ontarian has proved himself to be the world's fastest human being and has broken

Canadian, Commonwealth and World Cup 100-meter records," it read. "Recipient of the Norton Crowe Award

for Male Athlete of the Year for 1985, 'Big Ben' was the winner of the 1986 Lou Marsh Trophy as Canada's top

athlete."

By the time of the 1987 World Championships, Johnson had won his four previous races with Lewis and had

established himself as the best 100 m sprinter. At Rome, Johnson gained instant world fame and confirmed this](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-9-2048.jpg)

![status when he beat Lewis for the title, setting a new world record of 9.83 seconds as well, beating Calvin

Smith's former record by a full tenth of a second.

After Rome, Johnson became a lucrative marketing celebrity. According to coach Charlie Francis, after

breaking the world record, Johnson earned about $480,000 a month in endorsements.[2] Johnson won both the

Lou Marsh Trophy and Lionel Conacher Award, and was named the Associated Press Athlete of the Year for

1987.

Following Johnson's defeat of Lewis in Rome, Lewis started trying to explain away his defeat. He first claimed

that Johnson had false-started, then he alluded to a stomach virus which had weakened him. Finally, without

naming names, Lewis said "There are a lot of people coming out of nowhere. I don’t think they are doing it

without drugs." This was the start of Lewis’ calling on the sport of track and field to be cleaned up in terms of

the illegal use of performance-enhancing drugs. While cynics noted that the problem had been in the sport for

many years, they pointed out that it didn’t become a cause for Lewis until he was actually defeated, with some

also pointing to Lewis's egotistical attitude and lack of humility. During a controversial interview with the BBC,

Lewis said:[3]

There are gold medallists at this meet who are on drugs, that [100 metres] race will be looked at for many years,

for more reasons than one.

Johnson's response was:

When Carl Lewis was winning everything, I never said a word against him. And when the next guy comes

along and beats me, I won’t complain about that either.

This set up the rivalry leading into the 1988 Olympic Games.

In 1988, Johnson experienced a number of setbacks to his running career. In February of that year he pulled a

hamstring, and in May he aggravated the same injury. Meanwhile in Paris in June, Lewis ran a 9.99. Then in

Zurich, Switzerland on August 17, the two faced each other for the first time since the 1987 World

Championships, Lewis won in 9.93, while Johnson finished third in 10.00. "The gold medal for the (Olympic)

100 meters is mine," Carl Lewis said. "I will never again lose to Johnson."[3]

Olympic win and subsequent disqualification

On September 24, 1988, Johnson beat Lewis in the 100m final at the Olympics, lowering his own world record

to 9.79 seconds. Johnson would later remark that he would have been even faster had he not raised his hand in

the air just before he finished the race.[4] However, Johnson's urine samples were found to contain stanozolol,

and he was disqualified three days later. He later admitted having used steroids when he ran his 1987 world

record, which caused the IAAF to rescind that record as well. Johnson and coach Francis complained that they

used doping in order to remain on an equal footing with the other top athletes on drugs they had to compete

against. In testimony before the Dubin inquiry into drug use, Francis charged that Johnson was only one of

many cheaters, and he just happened to get caught. Later, five of the finalists of the 100-meter race tested

positive for banned drugs or were implicated in a drug scandal at some point in their careers: Carl Lewis, who

was given the gold medal, Linford Christie, who was moved up to the silver medal and who went on to win

gold at the next Games, Dennis Mitchell, who was moved up to fourth place and finished third to Christie in

1992, and Desai Williams, Johnson's countryman who won a bronze medal at the Los Angeles Games in

1984.[5]

Johnson's coach, Charlie Francis, a vocal critic of the IOC testing procedures, is the author of Speed Trap,

which features Johnson heavily. In the book, he freely admits that his athletes were taking anabolic steroids, as](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-10-2048.jpg)

![he claims all top athletes at the time were, and also claims that Johnson could not possibly have tested positive

for that particular steroid since Johnson actually preferred furazabol. He thought stanozolol made his body "feel

tight".[6]

The Canadian reaction to 9.79 seconds

Canadians rejoiced in the reflected glory of winning the gold medal and breaking the world record.

Newspapers covered the occasion by concocting words such as "Benfastic" (Toronto Star, September 25, 1988)

to describe it. Two days later, Canadians witnessed the downfall of Johnson, when he was stripped of his gold

medal and world record. In the first week following the dethroning, Canadian newspapers devoted between five

to eight pages a day to the story. Some squarely placed the blame on Johnson, such as one headline right after

the exposure suggests: "Why, Ben?" (Toronto Sun, September 26, 1988).

Because of the Olympic scandal, The Canadian news agency, Canadian Press, named Johnson "Newsmaker of

the Year" for 1988.

The Dubin Inquiry

After the Seoul test, he initially denied doping, but, testifying before the 1989 Dubin Inquiry, a Canadian

government investigation into drug abuse, Johnson admitted that he had lied. Charlie Francis, his coach, told the

inquiry that Johnson had been using steroids since 1981.

In Canada, the federal government established the Commission of Inquiry Into the Use of Drugs and Banned

Practices Intended to Increase Athletic Performance, headed by Ontario Appeal Court Chief Justice Charles

Dubin. The Dubin Inquiry (as it became known), which was televised live, heard hundreds of hours of

testimony about the widespread use of performance-enhancing drugs among athletes. The inquiry began in

January 1989 and lasted 91 days, with 122 witnesses called, including athletes, coaches, sport administrators,

IOC representatives, doctors and government officials.

Comeback

In 1991, after his suspension ended, he attempted a comeback. He returned to the track for the Hamilton Indoor

Games in 1991 and was greeted by the largest crowd to ever attend an indoor Canadian track and field event.

More than 17,000 people saw him finish second in the 50 metres in 5.77 seconds.

He failed to qualify for the 1991 World Championships in Tokyo but made the Canadian Olympic team again in

1992 in Barcelona, Spain after finishing second at the Canadian Olympic trials to Bruny Surin.[7] He missed the

100 metre finals at the Olympics however, finishing last in his semi-final heat after stumbling out of the blocks.

In 1993, he won the 50 metres on February 7 in Grenoble, France, in 5.65 seconds, just 0.04 seconds shy of the

world record. However in January 1993, he was found guilty of doping at a race in Montreal - this time for

excess testosterone - and was subsequently banned for life by the IAAF. Federal amateur sport minister Pierre

Cadieux called Johnson a national disgrace, and suggested he consider moving back to Jamaica. Johnson

commented that it was "by far the most disgusting comment [he had] ever heard."[8] In April 1999, a Canadian

adjudicator ruled that there were procedural errors in Johnson's lifetime ban and allowed him to appeal. The

decision meant Johnson could technically run in Canada but nobody would compete against him. They would

be considered "contaminated" by the IAAF and could also face sanctions. On June 12, 1999, Johnson entered a

track meet in Kitchener, Ontario, and was forced to run alone, against the clock. He posted a time of 11.0

seconds. In late 1999, Johnson failed a drug test for the third time by testing positive for hydrochlorothiazide, a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-11-2048.jpg)

![banned diuretic that can be used to mask the presence of other drugs. Johnson had not competed since 1993 and

had arranged the test himself as part of his efforts to be reinstated.

Al-Saadi Gaddafi training stint

In 1999, Johnson made headlines again when it was revealed that he had been hired by Libyan leader Muammar

Gaddafi to act as a football coach for his son, Al-Saadi Gaddafi, who aspired to join an Italian football club. Al-

Saadi ultimately did join an Italian team but was sacked after one game when he failed a drug test. Johnson's

publicist in Canada had predicted in The Globe and Mail that his training of the young Gaddafi would earn

Johnson a Nobel Peace Prize.

Late 1990s and beyond

Johnson briefly acted as trainer for Argentine football legend Diego Maradona in 1997. This occurred at York

University, Toronto.[9]

In 1998, Johnson appeared in a charity race in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, where he raced against a

thoroughbred race horse, a harness racing horse and a stock car.[10] Johnson finished third in the race.

According to a 1998 article in Outside magazine, Johnson spent much of the latter part of the 1990s living

downstairs in the house he shared with his mother Gloria. He spent his leisure time reading, watching movies

and Roadrunner cartoons, and taking his mother to church. He lived in a spacious home in Newmarket,

Ontario's Stonehaven neighborhood. He claims to have lost his Ferrari when he used it as collateral for a loan

from an acquaintance in order to make a house payment.[11] Gloria died of cancer in 2004 and Johnson lived

with his sister afterwards.

Shortly after his leaving Libya, it was reported that Johnson had been robbed of $7,300 by a Romany gang in

Rome. His wallet was taken, containing $7,300 in cash, the proceeds of his pay for training Gaddafi. Johnson

gave chase, but was unable to catch them after they vanished into a subway station.[12]

In May 2005, Johnson launched a clothing and sports supplement line, the Ben Johnson Collection. The motto

for Johnson's clothing line was "Catch Me"; however, the clothing line never took off.[13]

In a January 1, 2006 interview, [14] Johnson claimed that he was sabotaged by a "Mystery Man"[15] inside the

doping-control room immediately following the 100m final in Seoul. He also stated that 40% of people in the

sports world are still taking drugs to improve their performance.

In March 2006, television spots featuring Johnson advertising an energy drink, "Cheetah Power Surge", started

to receive some airtime. Some pundits questioned whether Johnson was an appropriate spokesperson for an all

natural energy drink considering his history of steroid use.[16][17] One ad is a mock interview between Johnson

and Frank D'Angelo, the president and chief executive of D'Angelo Brands, which makes the drink, in which he

asks Johnson: "Ben, when you run, do you Cheetah?". "Absolutely," says Johnson. "I Cheetah all the time."[18]

The other commercial includes Johnson and a cheetah, the world's fastest land animal, and encourages viewers

to "go ahead and Cheetah."[18]

In August 2008, Johnson filed a $37 million lawsuit against the estate of his former lawyer Ed Futerman,

claiming Futerman made unauthorized payments from his trust account to pay bills and 20 percent commissions

to a hairdresser recruited by the lawyer to act as the sprinter's sports agent.

At present, Johnson lives in Markham, Ontario and spends much of his time with his daughter and

granddaughter. He also continues to coach. In 2010, he released his autobiography entitled Seoul to Soul.[13] In](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-12-2048.jpg)

![the self-published book, Johnson reviews his childhood in Jamaica, and his early bout with malaria. A Canadian

Press article described the book as "an unconventional sports autobiography."[19]

Ben Jonson was born around June 11, 1572, the posthumous son of a clergyman. He

was educated at Westminster School by the great classical scholar William Camden and

worked in his stepfather's trade, bricklaying. The trade did not please him in the least,

and he joined the army, serving in Flanders. He returned to England about 1592 and

married Anne Lewis on November 14, 1594.

Jonson joined the theatrical company of Philip Henslowe in London as an actor and

playwright on or before 1597, when he is identified in the papers of Henslowe. In 1597

he was imprisoned in the Fleet Prison for his involvement in a satire entitled The Isle of

Dogs, declared seditious by the authorities. The following year Jonson killed a fellow

actor, Gabriel Spencer, in a duel in the Fields at Shoreditch and was tried at Old Bailey

for murder. He escaped the gallows only by pleading benefit of clergy. During his

subsequent imprisonment he converted to Roman Catholicism only to convert back to

Anglicism over a decade later, in 1610. He was released forfeit of all his possessions,

and with a felon's brand on his thumb.

Jonson's second known play, Every Man in His Humour, was performed in 1598 by the Lord Chamberlain's Men at the

Globe with William Shakespeare in the cast. Jonson became a celebrity, and there was a brief fashion for 'humours'

comedy, a kind of topical comedy involving eccentric characters, each of whom represented a temperament, or humor, of

humanity. His next play, Every Man Out of His Humour (1599), was less successful. Every Man Out of His Humour and

Cynthia's Revels (1600) were satirical comedies displaying Jonson's classical learning and his interest in formal

experiment.

Jonson's explosive temperament and conviction of his superior talent gave rise to "War of the Theatres". In The Poetaster

(1601), he satirized other writers, chiefly the English dramatists Thomas Dekker and John Marston. Dekker and Marston

retaliated by attacking Jonson in their Satiromastix (1601). The plot of Satiromastix was mainly overshadowed by its

abuse of Jonson. Jonson had portrayed himself as Horace in The Poetaster, and in Satiromastix Marston and Dekker, as

Demetrius and Crispinus ridicule Horace, presenting Jonson as a vain fool. Eventually, the writers patched their feuding;

in 1604 Jonson collaborated with Dekker on The King's Entertainment and with Marston and George Chapman on

Eastward Ho.

Jonson's next play, the classical tragedy Sejanus, His Fall (1603), based on Roman history and offering an astute view of

dictatorship, again got Jonson into trouble with the authorities. Jonson was called before the Privy Council on charges of

'popery and treason'. Jonson did not, however, learn a lesson, and was again briefly imprisoned, with Marston and

Chapman, for controversial views ("something against the Scots") espoused in Eastward Ho (1604). These two incidents

jeopardized his emerging role as court poet to King James I. Having converted to Catholicism, Jonson was also the object

of deep suspicion after the Gunpowder Plot of Guy Fawkes (1605).

In 1605, Jonson began to write masques for the entertainment of the court. The earliest of his masques, The Satyr was

given at Althorpe, and Jonson seems to have been appointed Court Poet shortly after. The masques displayed his

erudition, wit, and versatility and contained some of his best lyric poetry. Masque of Blacknesse (1605) was the first in a

series of collaborations with Inigo Jones, noted English architect and set designer. This collaboration produced masques

such as The Masque of Owles, Masque of Beauty (1608), and Masque of Queens (1609), which were performed in Inigo

Jones' elaborate and exotic settings. These masques ascertained Jonson's standing as foremost writer of masques in the

Jacobean era. The collaboration with Jones was finally destroyed by intense personal rivalry.

Jonson's enduring reputation rests on the comedies written between 1605 and 1614. The first of these, Volpone, or The

Fox (performed in 1605-1606, first published in 1607) is often regarded as his masterpiece. The play, though set in Venice,

directs its scrutiny on the rising merchant classes of Jacobean London. The following plays, Epicoene: or, The Silent

Woman (1609), The Alchemist (1610), and Bartholomew Fair (1614) are all peopled with dupes and those who deceive

them. Jonson's keen sense of his own stature as author is represented by the unprecedented publication of his Works, in

folio, in 1616. He was appointed as poet laureate and rewarded a substantial pension in the same year.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-13-2048.jpg)

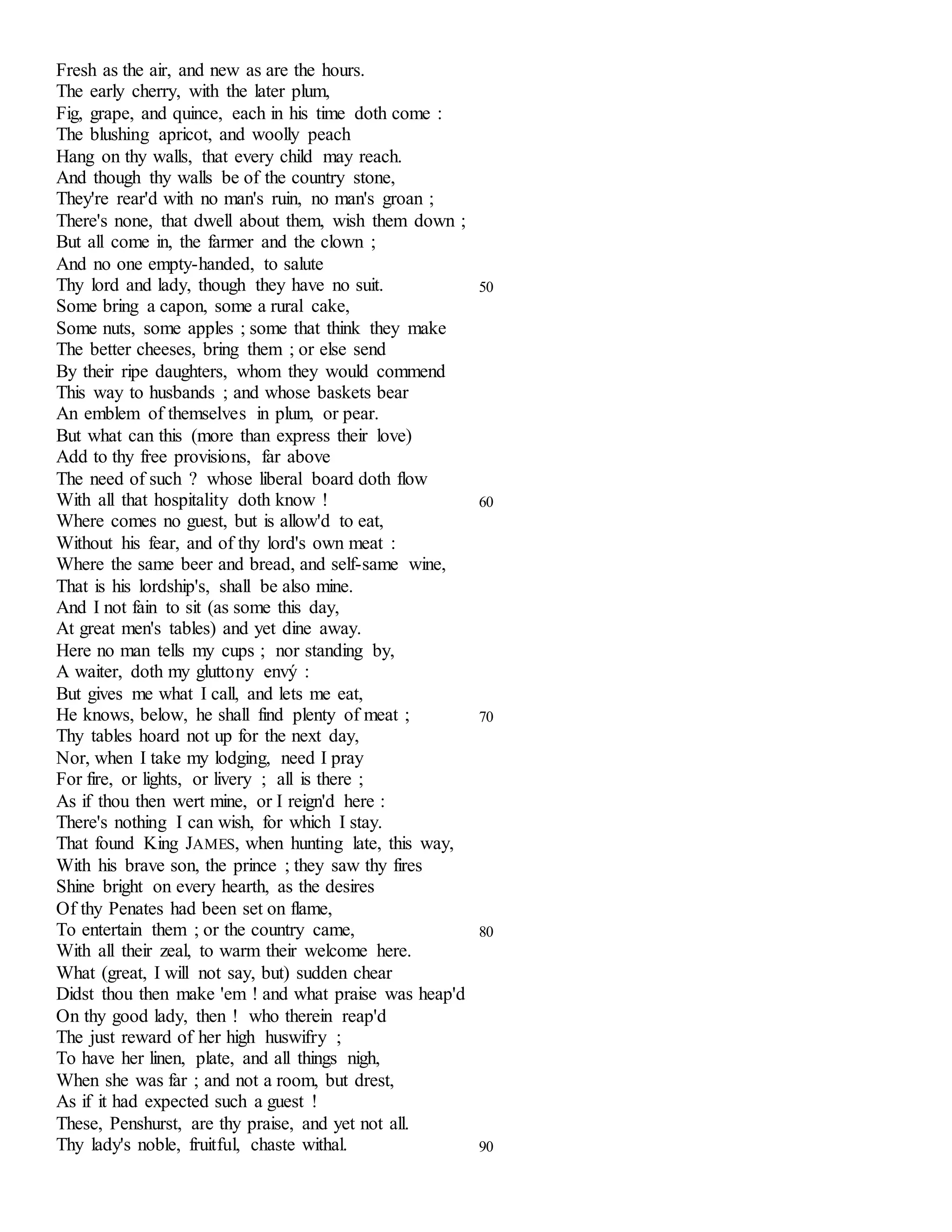

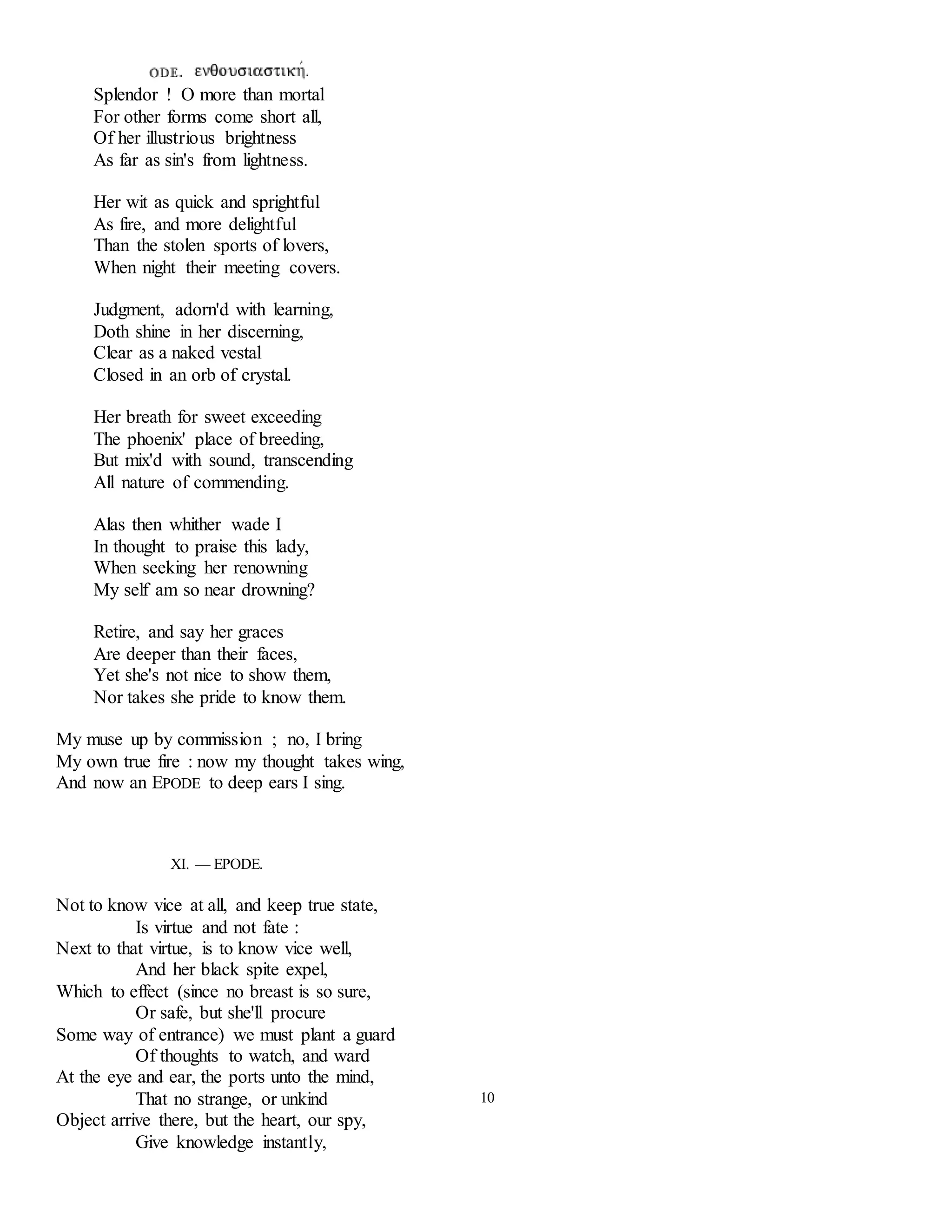

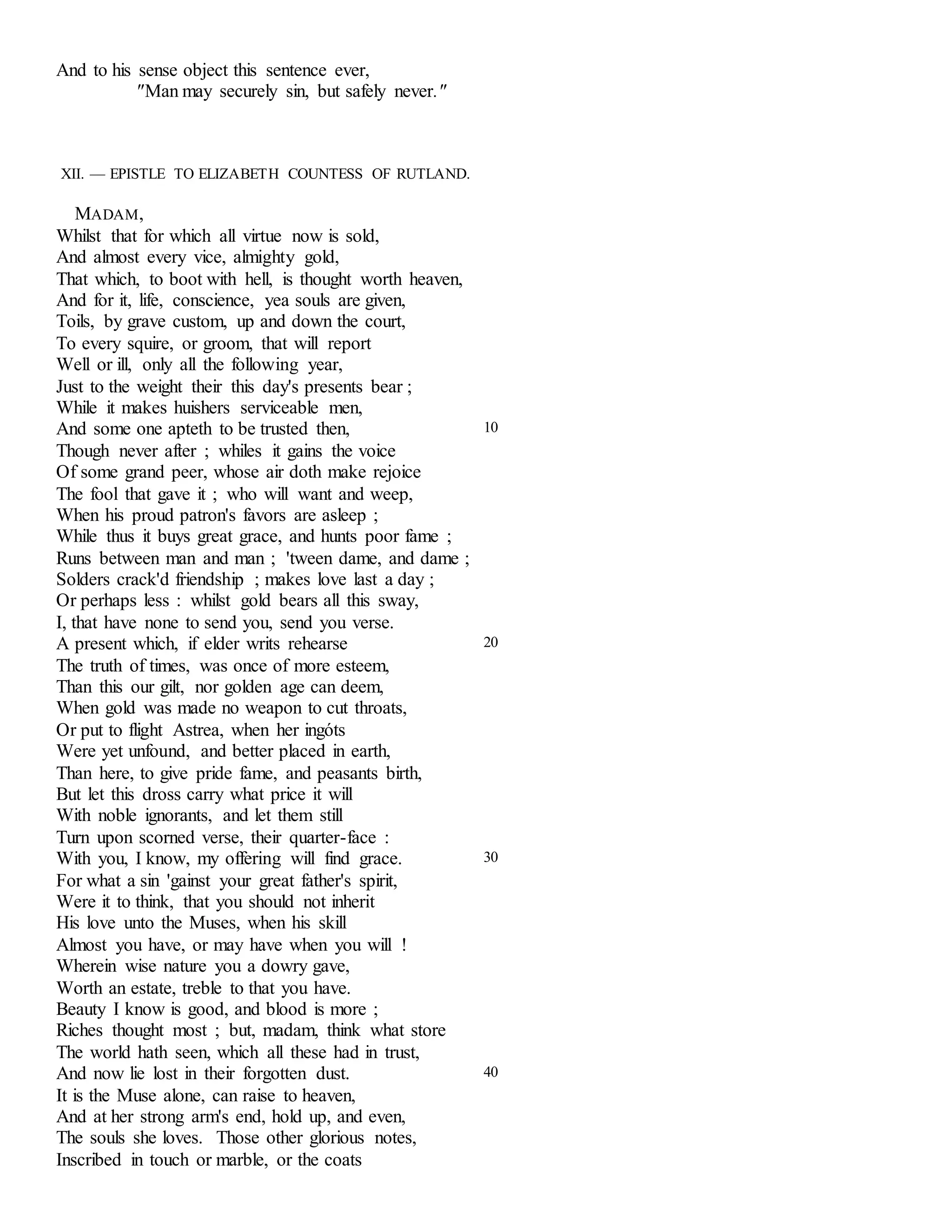

![I: To The Reader

II: To My Book

III: To My Bookseller

IV: To King James

V: On the Union

VI: To Alchemists

VII: On the New Hot-House

VIII: On a Robbery

IX: To All, To Whom I Write

X: To My Lord Ignorant

XI: On Something That Walks Somewhere

XII: On Lieutenant Shift

XIII: To Doctor Empiric

XIV: To William Camden

XV: On Court-Worm

XVI: To Brainhardy

XVII: To the Learned Critic

XVIII: To My Mere English Censurer

XIX: On Sir Cod the Perfumed

XX: To the Same. [Sir Cod the Perfumed]

XXI: On Reformed Gam'ster

XXII: On My First Daughter

XXIII: To John Donne

XXIV: To the Parliament

XXV: On Sir Voluptuous Beast

XXVI: On the Same

XXVII: On Sir John Roe

XXVIII: On Don Surly

XXIX: To Sir Annual Tilter

XXX: To Person Guilty

XXXI: On Banks the Usurer

XXXII: On Sir John Roe (II)

XXXIII: To the Same

XXXIV: Of Death

XXXV: To King James (II)

XXXVI: To the Ghost of Martial

XXXVII: On Cheveril the Lawyer

XXXVIII: On Person Guilty

XXXIX: On Old Colt

XL: On Margaret Ratcliffe

XLI: On Gipsy

XLII: On Giles and Joan

XLIII: To Robert Earl of Salisbury

XLIV: On Chuffe, Banks the Usurer's Kinsman

XLV: On my First Son

XLVI: To Sir Luckless Woo-All

XLVII: To the Same

XLVIII: On Mungril Esquire](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-18-2048.jpg)

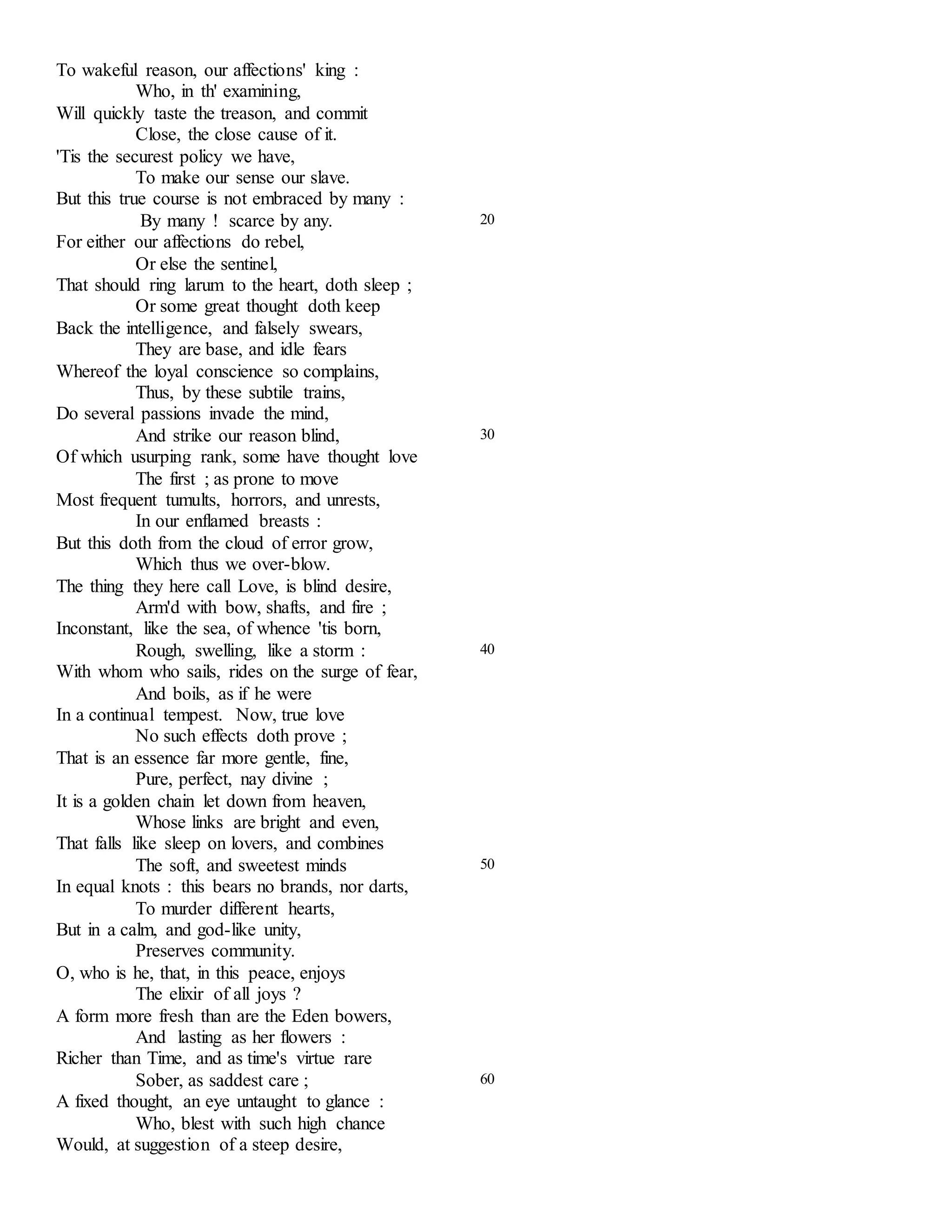

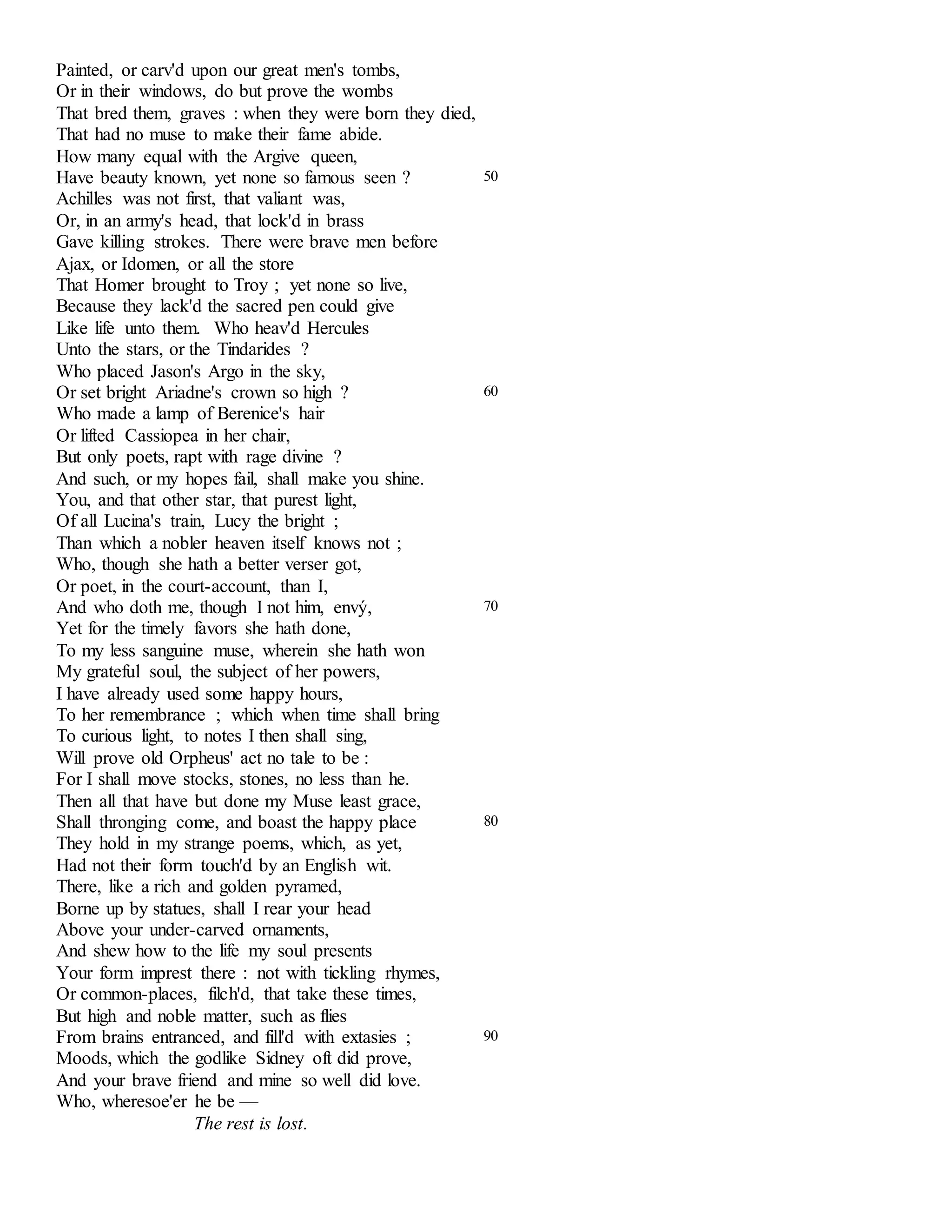

![XLIX: To Playwright

L: To Sir Cod

LI: To King James

LII: To Censorious Courtling

LIII: To Oldend Gatherer

LIV: On Cheveril

LV: To Francis Beaumont

LVI: On Poet-Ape

LVII: On Bawds and Usurers

LVIII: To Groom Idiot

LIX: On Spies

LX: To William Lord Mounteagle

LXI: To Fool, or Knave

LXII: To Fine Lady Would-Be

LXIII: To Robert Earl of Salisbury

LXIV: To the Same. Upon the Accession of the Treasurership to him. [Robt E. Salisbury]

LXV: To my Muse

LXVI: To Sir Henry Cary

LXVII: To Thomas Earl of Suffolk

LXVIII: On Playwright

LXIX: To Pertinax Cob

LXX: To William Roe

LXXI: On Court Parrot

LXXII: To Courtling

LXXIII: To Fine Grand

LXXIV: To Thomas Lord Chancellor

LXXV: On Lippe the Teacher

LXXVI: To Lucy Countess of Bedford

LXXVII: To One that Desired Me Not to Name Him

LXXVIII: To Hornet

LXXIX: To Elizabeth, Countess of Rutland

LXXX: Of Life and Death

LXXXVI: To the Same. [H. Goodyere]

LXXXIX: To Edward Allen (Alleyne)

XCIV: To Lucy, Countess of Bedford, with John Donne's Satires

CI: Inviting a Friend to Supper

CV: To Mary Lady Wroth

CXVIII: On Gut

CXX: An Epitaph on S [alathiel] P [avy]

CXXIV: Epitaph on Elizabeth, L.H.

CXXVIII: To William Roe

Complete - Luminarium Editions

I: Why I Write Not Of Love

II: To Penshurst

III: To Sir Robert Wroth

IV: To the World: A Farewell for a Gentlewoman, Virtuous and Noble](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-19-2048.jpg)

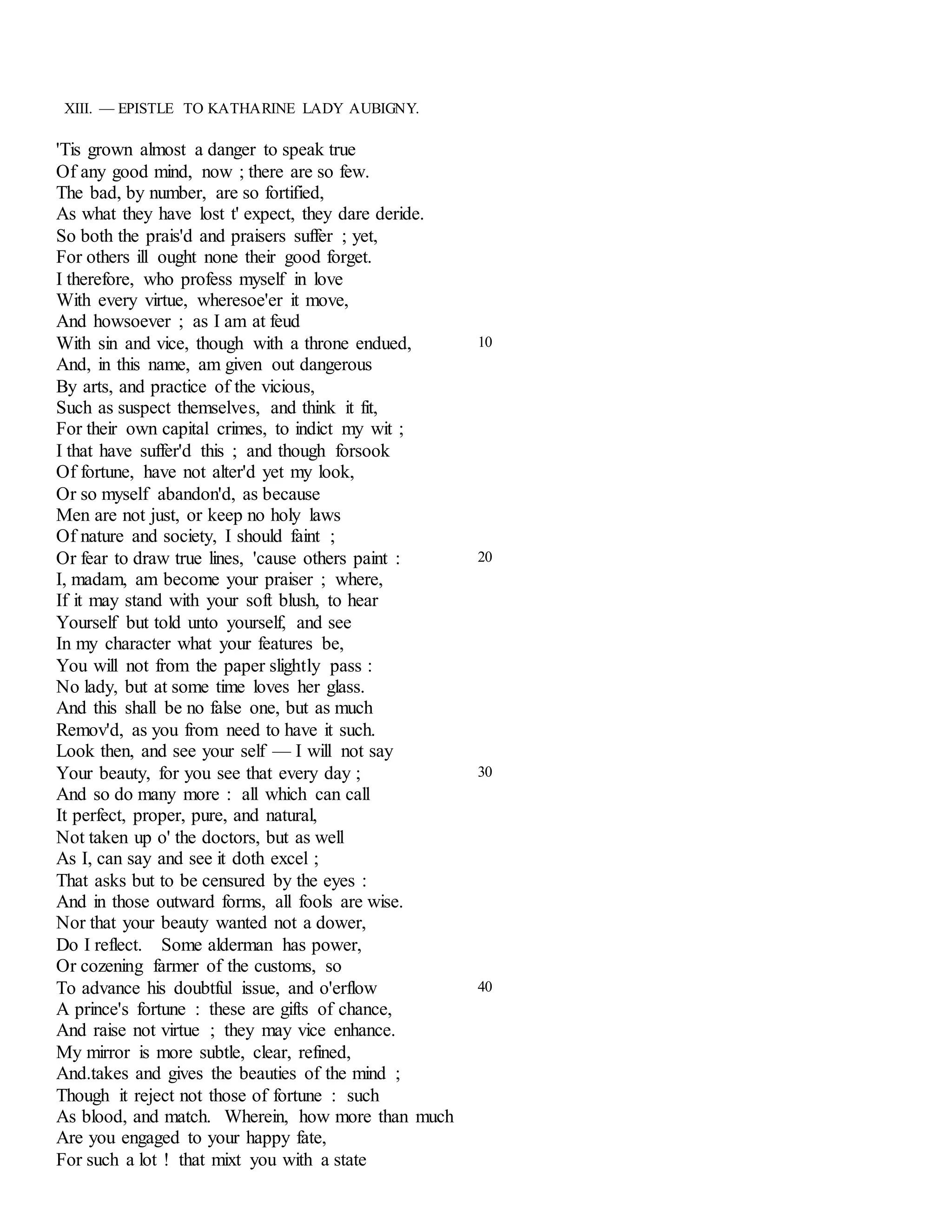

![V: Song To Celia ("Come my Celia, let us prove")

VI: To the Same ("Kiss me, Sweet")

VII: Song. That Women Are But Men's Shadows

VIII: Song. To Sickness

IX: To Celia ("Drink to me only with thine eyes")

X: Præludium ("And must I sing?")

XI: Epode ("Not to know vice at all")

XII: Epistle to Elizabeth, Countess of Rutland

XIII: Epistle to Katherine, Lady Aubigny

XIV: Ode to Sir William Sidney, on His Birthday

XV: To Heaven

Poems of Devotion

2. An Hymn to God the Father

3. An Hymn on the Nativity of My Savior

I: His Excuse for Loving Audio

II: How he saw Her

III: What he Suffered

IV: Her Triumph

V: His Discourse with Cupid

VI: Claiming a Second Kiss by Desert

VII: Begging Another

VIII: Urging her of a Promise

IX: Her Man described by her own Dictamen

X: Another Lady's Exception, present at the Hearing

Miscellaneous Poems

1. The Musical Strife. A Pastoral Dialogue

2. A Song [Oh, do not wanton with those eyes]

3. In the Person of Womankind. A Song Apologetic.

5. A Nymph's Passion

6. The Hour-Glass

7. My Picture Left in Scotland Audio

8. Against Jealousy

9. The Dream

10. An Epitaph on Master Vincent Corbet

11. On the Portrait of Shakspeare

12. To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare

14. To Mr. John Fletcher, Upon His "Faithful Shepherdess"

15. Epitaph on the Countess of Pembroke

17. Epitaph on Michael Drayton

19. To His Much and Worthily Esteemed Friend, the Author

20. To My Worthy and Honored Friend, Master George Chapman](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-20-2048.jpg)

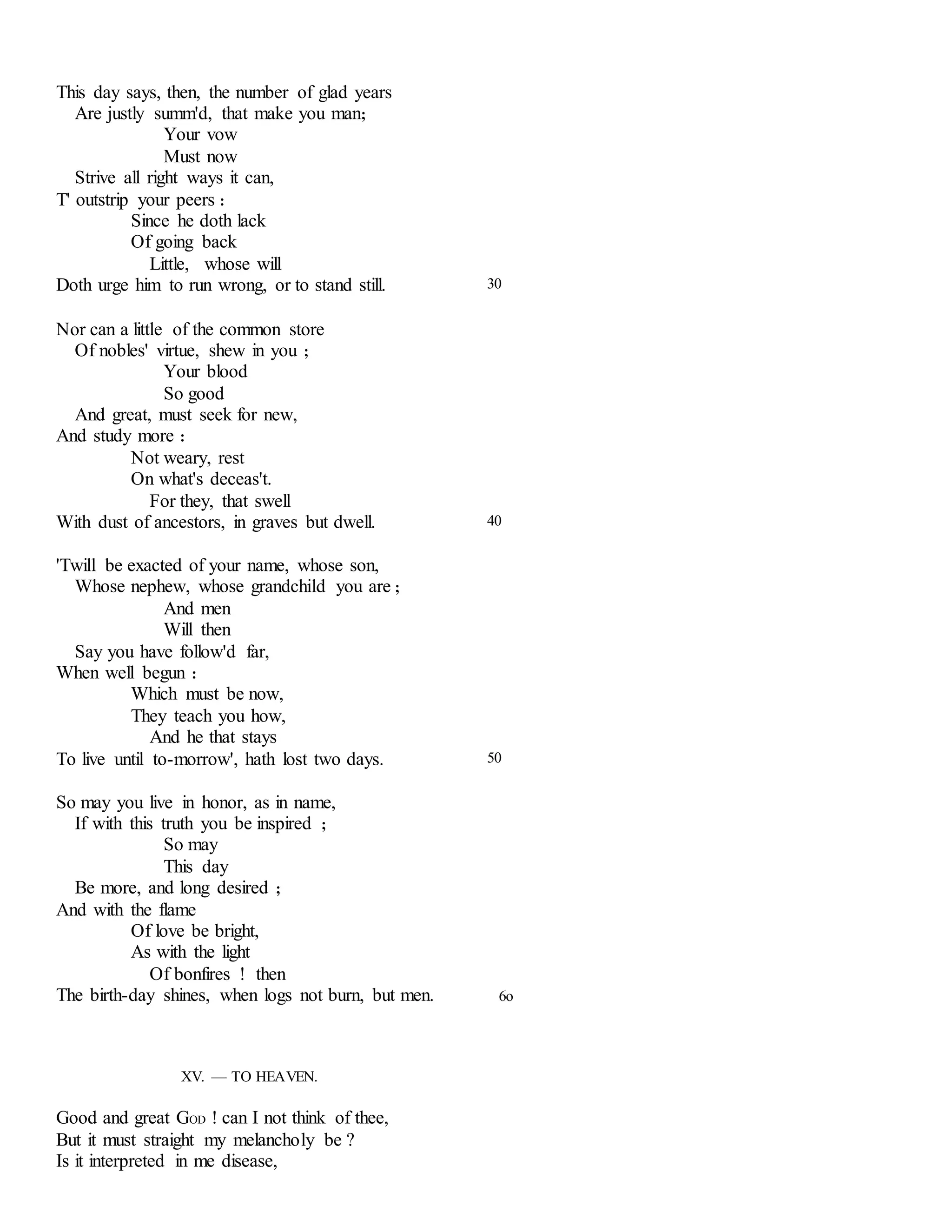

![23. Epigram. In Authorem. [re: Nicholas Breton]

25. To the Author [re: Thomas Wright]

26. To the Author [re: T. Warre]

36. An Elegy [By those bright eyes]

39. An Elegy [Though beauty be the mark of praise]

41. An Ode to Himself [Where dost Thou careless lie]

42. The Mind of the Frontispiece to a Book

44. An Ode [High-spirited friend]

46. A Sonnet, to the Noble Lady, the Lady Mary Worth [I that have been a lover]

47. A Fit of Rhyme against Rhyme

57. An Elegy [To make the doubt clear]

59. An Elegy [Since you must go]

60. An Elegy [Let me be what I am]

68. An Epigram, to the Honored Countess of * * *

69. On Lord Bacon's Birthday

77. An Epitaph on Henry Lord La-ware

87. A Pindaric Ode [To the Immortal Memory and Friendship of that Noble Pair....]

92. To the Right Honorable Hierome, Lord Weston

93. Epithalamion ; Or, A Song

100. An Elegy on the Lady Jane Pawlet, Marchioness of Winton

To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare

Ode to Himself upon the Censure of his "New Inn"

"This is Mab, the mistress-fairy" (The Particular Entertainment of the Queen and Prince at Althrope)

"Of Pan we sing" (Pan's Anniversary)

"Slow, slow, fresh fount" (Cynthia's Revels)

"Oh, that joy so soon should waste" (Cynthia's Revels)

"Queen, and huntress, chaste and fair" (Cynthia's Revels)

"If I freely may discover" (The Poetaster)

"Swell me a bowl" (The Poetaster)

"Still to Be Neat" (Epicoene, or the Silent Woman)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-21-2048.jpg)

!["Though I Am Young and Cannot Tell" (The Sad Shepherd)

"The faery beam upon you" (The Gypsies Metamorphosed)

"To the old, long life and treasure" (The Gypsies Metamorphosed)

"So breaks the sun earth's rugged chains" (The Irish Masque)

Plays

The Alchemist - Project Gutenberg

Bartholomew Fair - UMichigan

The Case is Altered - Holloway Pages

Catiline - Holloway Pages

Cynthia's Revels - Project Gutenberg

The Devil is an Ass - Holloway Pages

Eastward Ho - Holloway Pages

Epicoene - Project Gutenberg

Every Man in His Humour - Project Gutenberg

Every Man Out of His Humor - Luminarium Editions

The Magnetic Lady - Holloway Pages

Mortimer his Fall (Fragment) - Holloway Pages

New Inn - Holloway Pages

The Poetaster - Project Gutenberg

The Sad Shepherd, or a Tale of Robin Hood - Univ. of Rochester

Sejanus - Project Gutenberg

The Staple of News - Holloway Pages

A Tale of a Tub - Holloway Pages

Volpone, or The Fox - Project Gutenberg

Volpone, or The Fox - Full Manuscript Image Facsimile at SCETI

Masques

A Challenge at Tilt - Holloway Pages

The Fortunate Isles, and Their Union - GB

The Golden Age Restored (1616) - Luminarium Editions

Gypsies Metamorphosed - Google Books

The Irish Masque - Holloway Pages

Love Freed from Ignorance and Folly - Holloway Pages

Love Restored (1612) - Luminarium Editions

Masque of Augurs - Google Books

The Masque of Hymen (aka Hymenæ) (1606) - Luminarium Editions

The Masque of Owls - Google Books

[Excerpt]

Masque of Queens (1609) - Holloway Pages

Mercury Vindicated from the Alchemists (1615) - Luminarium Editions

Neptune's Triumph for the Return of Albion - Google Books

News from the New World - Dartmouth](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-22-2048.jpg)

![Oberon, the Fairy Prince (1611) - Luminarium Editions

The Queen's Masques

The Masque of Blackness (1605) - Luminarium Editions

The Masque of Beauty (1608) - Renascence Editions

Pan's Anniversary - Google Books

Prince Henry's Barriers - Holloway Pages

Time Vindicated to Himself & To His Honours - Google Books

Timber: Or, Discoveries - Project Gutenberg

Timber: Or Discoveries

Excerpt from Timber: Or Discoveries

Another Excerpt from Timber: Or Discoveries [Bacon]

Another Excerpt from Timber: Or Discoveries [Bacon 2]

Another Excerpt from Timber: Or Discoveries [Shakespeare]

Two Jonson Poems in Russian

These essays are not intended to replace library research. They are here to show

you what others think about a given subject, and to perhaps spark an interest or an

idea in you. To take one of these essays, copy it, and to pass it off as your own is

known as plagiarism—academic dishonesty which will result (in every university

I've heard tell of) in suspension or dismissal from the university. Not only are your

professors as technology-savvy as you are, they will not tolerate theft of another's

intellectual efforts.

Nota bene:

Background and code copyright ©1996-2010 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

=Student Essay

THE PLAYS:

Dissertation: "Falling to a devilish exercise": Magic and Spectacle on the Renaissance Stage - Shayne Confer

Dissertation: Health Imagery and Rhetoric in the Major Comedies of Ben Jonson - Leona F. Dale [.pdf]

Thesis: Dramatic Functions of Costuming in Plays by Ben Jonson - Emmett W. Cook [.pdf]

The Trickster-figure in Jacobean City Comedy - William R. Dynes

Stuart Civic Pageants and Textual Performance - David M. Bergeron](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-23-2048.jpg)

![The Alchemist

Thesis: Counterpoint: Its Use in Ben Jonson's The Alchemist - Gary Nored [.pdf]

Thesis: "There's Magic in the Web of It": White and Black Magic in Jonson, Marlowe and Shakespeare - Marnie Findlater [.pdf]

Suspense is Believing: The Reality of Ben Jonson's The Alchemist - Donald Beecher

Jonson's Satire of Puritanism in The Alchemist - Jeanette D. Ferreira-Ross [.pdf]

The Repudiation of the Marvelous: Jonson's The Alchemist and the Limits of Satire - Ian McAdam [.pdf]

From Costiveness to Comic Relief: Purgation in The Alchemist - Tony Perrello

The Alchemist and the Emerging Adult Private Playhouse - Anthony J. Ouellette

Explication of the Opening of The Alchemist - Nathan Cervo

Erasmus's 'Beggar Talk' and Jonson's Alchemist - Eric Sterling and Robert C. Evans

Imagining Alchemists and Magicians in New Atlantis, The Tempest, and The Alchemist - David Hurley

Dynamic Linguistic and Artistic Patterns in Jonson's The Alchemist - Amra Raza [.pdf]

Bartholomew Fair

'A more familiar straine': Puppetry and Burlesque, or, Translation as Debasement in Ben Jonson's Bartholomew Fair - Rui

Carvalho Homem [.pdf]

The Use of Booths in the Original Staging of Jonson's Bartholomew Fair - Gabriel Egan [.pdf]

The Puritan Dialectic of Law and Grace in Bartholomew Fair - Ian McAdam

Bartholomew Fair and Jonsonian Tolerance - G.M. Pinciss

The Law versus the Marketplace: Spontaneous Order in Jonson's Bartholomew Fair - Paul A. Cantor [.pdf]

The (Self)-Fashioning of Ezekiel Edgworth in Jonson's Bartholomew Fair - Jean MacIntyre

Ben Jonson's 'Civil Savages' - Rebecca Ann Bach

Jonson at the Fair: A Playwright's Career in Review - David Reinheimer

Ben Jonson Unmasked - Kathleen A. Prendergast

The Widow Hunt on the Tudor-Stuart Stage - Ira Clark

Epicoene

Thesis: Men Disguised as Women in Elizabethan Drama - Marion S. Karr [.pdf]

Dumb Reading: The Noise of the Mute in Jonson's Epicene - Adrian Curtin

Jonson's Gossips and the Stuart Family Drama - Kristen McDermott

"Things like truths, well feigned": Mimesis and Secrecy in Jonson's Epicoene - Reuben Sanchez

"On forfeit of your selves, think nothing true": Self-Deception in Ben Jonson's Epicoene - J. A. Jackson

Masculine Silence: 'Epicoene' and Jonsonian Stylistics - Douglas Lanier

Refashioning Society in Ben Jonson's Epicoene - Marjorie Swann

The Classical Context of Ben Jonson's "other youth" - Bruce Boehrer

Cross Dressing with a Difference: The Roaring Girl and Epicoene - David Cope

Epicoene's Cosmetic Contingencies - Mary E. Brooks and Jenna H. Sharp

Every Man Out of His Humour

Jonson's Every Man Out and Commentators on Terence - Matthew Steggle

New Inn

'Wardrobe Stuffe': Clothes, Costume and the Politics of Dress in Ben Jonson's The New Inn - Julie Sanders

Some Uses for Romance: Shakespeare's Cymbeline and Jonson's The New Inn - Andrew Stewart

Ben Jonson's 'Civil Savages' - Rebecca Ann Bach

The Poetaster](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-24-2048.jpg)

![Undergrad Thesis: Gallimaufray and Hellebore: Spenser and Jonson in Dialogue with the Past - Ruth M. McAdams [.pdf]

The Pleasures of Restraint: The Mean of Coyness in Cavalier Poetry - Joshua Scodel

Ben Jonson Unmasked - Kathleen A. Prendergast

Sejanus

Thesis: Complexity of Character in Jonson's Sejanus - Jennifer D. Jones [.pdf]

Censorship and Representation in The Stuart Era: Three Roman Plays - David Cope [.pdf]

Jonson and the Neo-Classical Rules in Sejanus and Volpone - David Faley-Hills

Volpone

The Intertextualities of Ben Jonson's Volpone - James Tulip [.pdf]

Instances of Verbal Fraud in Jonson's Volpone - Elsa Simões Lucas Freitas [.pdf]

Volpone and the Ends of Comedy - Ian Donaldson [.pdf]

The Circle Pattern in Ben Jonson's Volpone - Jesús Cora Alonso [.pdf]

Volpone as a Non–Comedy - Farida Chishti [.pdf]

The Progress of Trickster in Ben Jonson's "Volpone" - Don Beecher

"In his gold I shine": Jacobean Comedy and the Art of the Mediating Trickster - Alizon Brunning

Jonson's Volpone and Dante - Christopher Baker and Richard Hart

Ben Jonson's Beastly Comedy: Outfoxing the Critics, Gulling the Audience in Volpone - Clifford Davis

In Changèd Shapes: The Two Jonsons' Volpones and Textual Editing - Karen Pirnie

The Setting of "Volpone" - Ralph A. Cohen

"Volpone"and the Old Comedy - P. H. Davison

Jonson and the Neo-Classical Rules in Sejanus and Volpone - David Faley-Hills

Unity of Theme in Volpone - Dorothy E. Litt

Volpone's "Sport" and the Structure of Jonson's Volpone - James D. Redwine, Jr.

Volpone: The Art of Deception - Miranda Johnson-Haddad

Jonson's Romish Foxe: Anti-Catholic Discourse in Volpone - Alizon Brunning

Ben Jonson Unmasked - Kathleen A. Prendergast

Volpone and Stage Androgyny in the English Renaissance - Celeste Collins

Volpone: Jonson's Experimentation with Comedy - Michael Williams

Antitheatricalism in Light of Ben Jonson's Volpone - Joel Culpepper

Shakespeare's Othello Compared to Jonson's Volpone - Jason

Other Plays

"Away, Stand off, I say": Women's Appropriations of Restraint and Constraint in

The Birth of Merlin and The Devil is an Ass - Sarah E. Johnson

'The top of woman! All her sex in abstract!': Ben Jonson

Directs the Boy Actor in The Devil is an Ass - Regina Buccola

The Appropriation of Pleasure in The Magnetic Lady - Helen Ostovich

MASQUES & ENTERTAINMENTS:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-25-2048.jpg)

!["The English Masque" - Felix E. Schelling mus t

Dissertation: Courtly Psychosis: The Rhetoric of Preferment in the Court Masque - Moira E. Phillips [.pdf]

Jonson's Masque Markets and Problems of Literary Ownership - Alison V. Scott

"But why do I describe what all must see?": Verbal Explication in the Stuart Masque - Agnieszka

Kolodziejska [.pdf]

Performing Love in Ben Jonson's Masques - Chris Hill [.pdf]

"Native Dyes": Race and Politics in the Jacobean Masque - Weidner & Walravens

Beyond the Emblem: Alchemical Albedo in Ben Jonson's The Masque of Blackness - Rafael Vélez Núñez

Emblems of Darkness: Othello (1604) and the Masque of Blackness (1605) - Manuel José Gómez Lara

Performing Devotion in The Masque of Blacknesse - Molly Murray

Beauty and the Beast: Images of Whiteness and Blackness from Jonson's The Masque of Blackness (1605) to

Richard Brome's The English Moor, or The Mock-Marriage (1637) - Athéna Efstathiou-Lavabre

Jonson's Gossips and the Stuart Family Drama - Kristen McDermott

The Three Faces of the Goddess in Ben Jonson's Masque of Queens - Maria Salomé Figueirôa Navarro

Machado

Amazon Reflections in the Jacobean Queen's Masque - Kathryn Schwarz

Culture de cour et idéologie: de l'usage de la pastorale dans le masque Pans Anniversarie de Ben Jonson -

Guillaume Forain [.pdf]

The Performing Heir in Jonson's Jacobean Masques - Jean E. Graham

The Problem in the Middle: Liminality in the Jonsonian Masque - Gregory A. Wilson

The Rhetoric of Place in Ben Jonson's 'Chorographical' Entertainments and Masques - Thomas Worden

Restoring Astraea: Jonson's Masque for the Fall of Somerset - Martin Butler and David Lindley

Marketing Luxury at the New Exchange: Jonson's Entertainment at Britain's Burse and the Rhetoric of Wonder

- Alison V. Scott

THE POETRY:

The Poetry of Ben Jonson - G. A. E. Parfitt

The Tone of Ben Jonson's Poetry - Geoffrey Walton

Ben Jonson's Poetry: Pastoral, Georgic, Epigram - Harris Friedberg

Ben Jonson and the Story of Charis - Ian Donaldson [.pdf]

Troping prostitution: Jonson and "The Court Pucell" - Victoria E. Price

'This truest glass': Ben Jonson's Verse Epistles and the Construction of the Ideal Patron - Colleen Shea

Literature as Equipment for Living: Ben Jonson and the Poetics of Patronage - Robert C. Evans

Stoicism and Plain Style in Ben Jonson: An Analysis of Some of His Verse Epistles - José María Pérez

Fernández

Liberty and History in Jonson's Invitation to Supper - Robert Cummings

A Case for the Epigram: Ben Jonson's "Inviting a Friend to Supper" - Meredith Goulding [.pdf]

"On the Famous Voyage": Ben Jonson and Civic Space - Andrew McRae

Horatian satire in Jonson's "On the Famous Voyage" - Bruce Boehrer

In the Person of Womankind: Female Persona Poems by Campion, Donne, Jonson - Pamela Coren

Ben Jonson and the 'Traditio Basiorum': Catullan imitation in 'The Forrest' 5 and 6 - Bruce Boehrer

Ben Jonson's 'On My First Son' and the Common Prayer Catechism - Jonquil Bevan](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-26-2048.jpg)

![Microhistory and Cultural Geography: Ben Jonson's "To Sir Robert Wroth" and the Absorption of Local

Community in the Commonwealth - Martin Elsky

Pirating Spain: Jonson's Commendatory Poetry and the Translation of Empire - Barbara Fuchs

"Man to man": Self-fashioning in Jonson's "To William Pembroke" - William Kolbrener

Ben Jonson's Poems: Notes on the Ordered Society - Hugh MacLean

"There are no accidents": Ben Jonson's construction of "Poet" - Joshua Messer

"To Penshurst"

Guess Who's Coming to Dinner? Reinterpreting Formalism and the Country House Poem - Heather Dubrow

Appropriating and Attributing the Supernatural in the Early Modern Country House Poem - A. D. Cousins and

R. J. Webb

From Common Wealth to Commonwealth: the Alchemy of "To Penshurst" - Hugh Jenkins

Sacramental Dwelling with Nature: Jonson's "To Penshurst" and Heidegger's "Building Dwelling

Thinking" - William E. Rogers [.pdf]

Landscape and Property in Seventeenth-Century Poetry - Andrew McRae [.pdf]

Poetry and Place in Drayton and Jonson - Canice J. Egan, S. J. [.pdf]

Ben Jonson and the Good Society - Jeffrey Hart [.pdf]

THE PROSE:

The Prose of Poets: Ben Jonson - Francis Thompson

JONSON & SHAKESPEARE:

Jonson's Ode to Shakespeare: What Was He Actually Saying? - Stephanie Hopkins Hughes[.pdf]

Afterlife: Jonson's "To the Memory... of Shakespeare" - Crystal Bartolovich

Mildmay Fane on Jonson and Shakespeare - Joseph T. Roy, Jr., and Robert C. Evans

Some Uses for Romance: Shakespeare's Cymbeline and Jonson's The New Inn - Andrew Stewart

Emblems of Darkness: Othello (1604) and the Masque of Blackness (1605) - Manuel José Gómez Lara

Disorder in the House of God: Disrupted Worship in Shakespeare and Others - Bruce Boehrer

Ben Jonson and The First Folio - W. Lansdown Goldsworthy

JONSON & THE CLASSICS:

Dissertation: Ben Jonson's Horatian Theory and Plautine Practice - D. Audell Shelburne [.pdf]

Jonson and the Classics - Stephen Dailly

Jonson's Stoic Politics: Lipsius, the Greeks, and the "Speach According to Horace" - Robert C. Evans

Horatian satire in Jonson's "On the Famous Voyage" - Bruce Boehrer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-27-2048.jpg)

![Jonson, Translation, and Horatian Lyric - Daniel Hooley

Ben Jonson and the 'Traditio Basiorum': Catullan imitation in 'The Forrest' 5 and 6 - Bruce Boehrer

Jonson's Every Man Out and Commentators on Terence - Matthew Steggle

Stoicism and Plain Style in Ben Jonson: An Analysis of Some of His Verse Epistles - José María Pérez

Fernández

"Powdered with Golden Rain": The Myth of Danae in Early Modern Drama - Julie Sanders

Jonson's Volpone and Dante - Christopher Baker and Richard Hart

The Classical Context of Ben Jonson's "other youth" - Bruce Boehrer

JONSON & OTHER AUTHORS:

Erasmus's 'Beggar Talk' and Jonson's Alchemist - Eric Sterling and Robert C. Evans

Jonson, Marlowe, and Epigram 77 - John Baker

Poetry and Place in Drayton and Jonson - Canice J. Egan, S. J. [.pdf]

Writing in Service: Sexual Politics and Class Position in the Poetry of Aemilia Lanyer and Ben Jonson - Ann

Baynes Coiro

'I Exscribe Your Sonnets': Jonson and Lady Mary Wroth - R.E. Pritchard

"But Worth pretends": Discovering Jonsonian Masque in Lady Mary Wroth's Pamphilia to Amphilanthus -

Anita M. Hagerman

"The strangest pageant, fashion'd like a court": John Donne and Ben Jonson to 1600 -- Parallel Lives - William

F. Blissett

Poetomachia and The Early Jonson: The Aesthetics of Topical Satire - David Cope

"Honesty and vulgar praise": The Poet's War and the Literary Field - Edward Gieskes

In the Person of Womankind: Female Persona Poems by Campion, Donne, Jonson - Pamela Coren

Jonson and Carew on Donne: Censure into Praise - John Lyon

Carew's response to Jonson and Donne - Scott Nixon

"By Lucan driv'n about": A Jonsonian Marvell's Lucanic Milton - Andrew Shifflett

'A silenc'st bricke-layer': An Allusion to Ben Jonson in Thomas Middleton's 'Masque.' - Jerzy Limon

Thomas Hobbes in Ben Jonson's 'The King's Entertainment at Welbeck' - A. P. Martinich

A "Double Portion of his Father's Art": Congreve, Dryden, Jonson and

The Drama of Theatrical Succession - Harold Weber

Collaborating with the Forebear: Dryden's Reception of Ben Jonson - Jennifer Brady

The Spanish Match Through the Texts: Jonson, Middleton, and Howell - F. Javier Sánchez Escribano

The Court Drama of Ben Jonson and Calderón - José Manuel González Fernández de Sevilla

Ben Jonson y Cervantes - Yumiko Yamada

Ben Jonson and Cervantes - Yumiko Yamada

GENERAL & MISCELLANEOUS:

T. S. Eliot's 1920 Essay on Ben Jonson

A Study of Ben Jonson - Algernon Charles Swinburne](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-28-2048.jpg)

![Revaluating Ben Jonson - Laurence Raw

Jonson the Master: Stones Well Squared - Fred Inglis

Tradition and Ben Jonson - L. C. Knights

Thesis: The Influence of Ben Jonson upon Ben Jonson - Leona F. Dale [.pdf]

Chapter 1 of Ben Jonson and Possessive Authorship - Joseph Loewenstein [.pdf]

Marking his Place: Ben Jonson's Punctuation - Sara van den Berg

The Poet of Labor: Authorship and Property in the Work of Ben Jonson - Bruce Thomas Boehrer

'Ut Pictura Poesis': Jonson and the Painted Subject - Gary Ettari [.pdf]

Invading Interpreters and Politic Picklocks: Reading Jonson Historically - Ian Donaldson [.pdf]

Ben Jonson and the Jonsonian Afterglow: Imagemes, Avatars, and Literary Reception - Anthony W.

Johnson [.pdf]

Ben Jonson's 1616 Folio: A Revolution in Print? - Lynn S. Meskill [.pdf]

Ben Jonson and His Folio - Clifford Stetner

Jonson and the Motives of Print - Richmond Barbour

Ben Jonson's Head - Jeffrey Masten

Biographical

Biography - Encyclopedia Britannica

Biography - Matt Steggle, Literary Encyclopedia

Biography - Theatre Database

Biography - The Columbia Encyclopedia

Biography - Theatrehistory.com

Biography - Britain Express

Biography - UVictoria

The Cambridge History of English and American Literature

in 18 Volumes (1907–21).

Ben Jonson - Ashley H. Thorndike

Ben Jonson’s character and friendships

Early life

Production of Every Man in His Humour

Maturity; Prosperity

Later years

Eminence in letters

Epigrams; The Forest

Underwoods

The Sad Shepherd

Early Plays](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-29-2048.jpg)

![ His Programme of Reform; Every Man in His Humour

Every Man out of His Humour

His Tragedies

Volpone; Epicoene

The Alchemist

Bartholomew Fayre

His later Comedies

His place in Literature

Marston's quarrel with Jonson: Assaults and Counter-assaults - W. Macneile Dixon

End of the quarrel - W. Macneile Dixon

Massinger's literary models: Shakespeare, Fletcher, Jonson - Emil Koeppel

General characteristics of the Jacobean and

Caroline Drama: the central position of Jonson - Rev. Ronald Bayne

The Pupils of Jonson: Nathaniel Field - Rev. Ronald Bayne

Field’s debt to Jonson - Rev. Ronald Bayne

Masque and Pastoral - Rev. Ronald Bayne

Ben Jonson’s Masques - Rev. Ronald Bayne

Rapid increase of dramatic elements in Jonson’s Masques - Rev. Ronald Bayne

Jonson’s later work in this field - Rev. Ronald Bayne

Ben Jonson’s The Sad Shepherd - Rev. Ronald Bayne

Ben Jonson’s Timber - Harold V. Routh

Jacobean and Caroline Criticism. Ben Jonson - J. E. Spingarn

Jonson’s literary“portraits” - J. E. Spingarn

Cavalier Lyrists. Influence of Jonson. - F. W. Moorman

Miscellaneous Metric: Jonson and Others - George Saintsbury

Perceptive Prosody: Jonson and Dryden - George Saintsbury

Images

Title-page of "Eastward Ho" (1605) - Columbia University

Title-page of The Workes of Beniamin Jonson, 1616. [114k]

Title-page of Jonson's Workes, 1640 - University of Sydney

Jonson miniature - Folger Library

Jonson's Signature - Folger Library

Engraving of Jonson from the 1692 Workes - Holloway Pages

Portrait of Jonson - Britannica

Jonson portrait - SAC LitWeb

The Grave of Ben Jonson

The Robert Vaughan portrait of Ben Jonson with an epithet by Dryden [91k]

Title-page of Every Man Out of His Humour, 1600. [54k]

Beardsley's illustration for Volpone,1898. [36k]

Pages from "Every Man Out of his Humour" (1616) - Columbia University

Actor List from "Sejanus, his Fall" - Columbia University

Title-page of Tragedies and Comedies (1633) [33k]

Inigo Jones: House of Fame Set Drawing [51k]

Oberon's Palace from "The Masque of Oberon"

Oberon's Palace from "The Masque of Oberon" (image 2) [231k]

Inigo Jones: Oberon from "The Masque of Oberon" [69k]

Satyrs and Fays from "The Masque of Oberon" [164k]

Inigo Jones: Female masquer [203k]

Inigo Jones: Male masquer [138k]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-30-2048.jpg)

![Inigo Jones Costume Plate from "Masque of Queens" [96k]

Inigo Jones: Daughter of Niger from "Masque of Blackness" (1605) [91k]

On Volpone

Study Questions forVolpone - Prof. Philip Mitchell

Study guide to Volpone - Prof. Theresa M. DiPasquale

Notes on Volpone - Prof. Arnie Sanders

Monstrous Characters in Volpone - Dr. Desmet, UGA

Discussion of Monsters in Volpone - English 434/ Dr. Desmet, UGA

Venice in Volpone - Jason

Miscellaneous

List of Jonson's Works - David Lewis

The Ben Jonson Journal

Study guide to Masque of Blacknesse - Theresa M. DiPasquale

Money Jonson - Jennifer W. Spirko

SAC LitWeb Jonson Page - Roger Blackwell Bailey

The Ben Jonson page - Matt Steggle

Oberon: Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones - UVictoria

Indigo "To Penshurst" - Prof. Clare Kinney

The Alchemy of Human Relations in Ben Jonson's The Alchemist - Dr. Desmet, UGA

The Alchemy of Human Relations in Ben Jonson's The Alchemist (PartII) - Dr. Desmet, UGA

On Jonson and Bacon - Martin Pares

On the presentation of The Masque of Beauty

Information on the Vaughan portrait

Herrick's poems on Ben Jonson

Carew's To Ben Jonson Upon Occasion of His Ode of Defiance

Frank's Creative Quotations from Ben Jonson

The Ben Jonson Journal

First Volume of "The Ben Jonson Journal" Published

A Digital Catalogue of Watermarks and Type Ornaments Used by WilliamStansby

in the Printing of THE WORKES OF BENIAMIN JONSON (London, 1616)

A Student's Bibliography for Jonson - Southwest Texas Community College

To buy a book from Amazon.com (US) just click on the title.

To buy a book from Amazon.co.uk (UK) use link under description (if available).

Biographical

Ben Jonson : A Life

by David Riggs

Paperback Reprint edition](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-31-2048.jpg)

![Bibliographical

Ben Jonson : A Quadricentennial Bibliography,

Nineteen Hundred and Forty-Seven Thru Nineteen

Hundred and Seventy-Two

by Dewey Heyward Brock

Hardcover

Scarecrow Pr, July 1974

Other

Critical Essays on Ben Jonson

(Critical Essays on British Literature)

by Robert N. Watson (Editor)

Hardcover

G K Hall, November 1997

"The essays are written by distinguished

commentators at both ends of the chrono-logical

range, from the 16th to the 20th

centuries. Together they provide the best

early case study of English literary

criticism." —Amazon.com

Full Description

Ben Jonson's Antimasques : A History of Growth and Decline

by Lesley Mickel

Hardcover

Ashgate Publishing Company; March 1999

"[D]iscusses in detail those court entertainments which

contributed significantly to the genre's evolution and

development. Her approach is innovative in that she

examines these works in relation to Jonson's poetry

and dramatic works. This reveals some idea of the way

in which Jonson perceived the relationship between

satire and panegyric, as well as highlighting the related,

if oppositional, views of state power which he expresses

in the Roman plays and in the masques."

—Amazon.co.uk

Full Description

Table of Contents

Order it from Amazon.co.uk

Jonson and the Contexts of His Time

by Robert C. Evans

Hardcover

Bucknell Univ Pr, May 1994

"By examining specific works, particular

historical circumstances, and complex](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asongtoselia-141124090445-conversion-gate01/75/A-song-to-selia-36-2048.jpg)