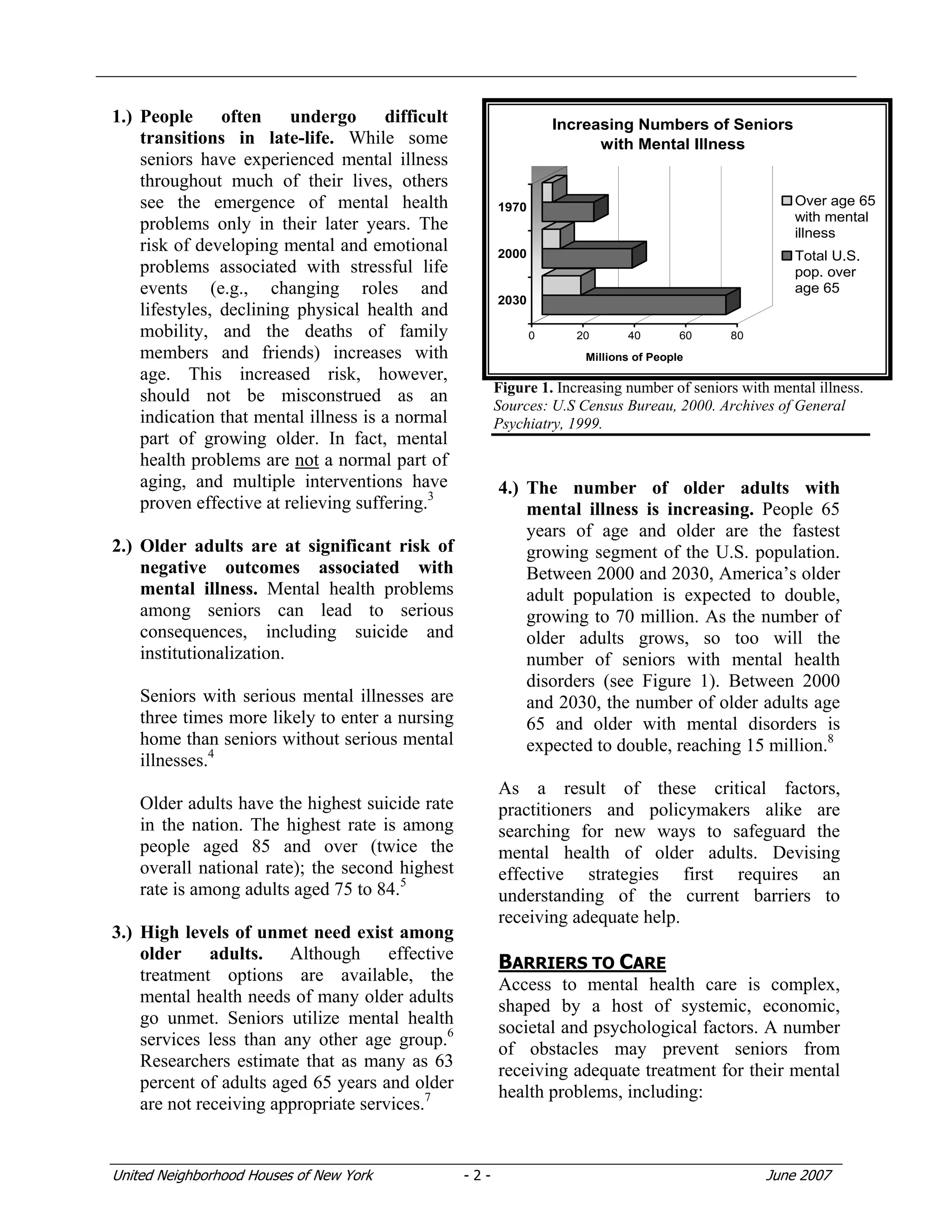

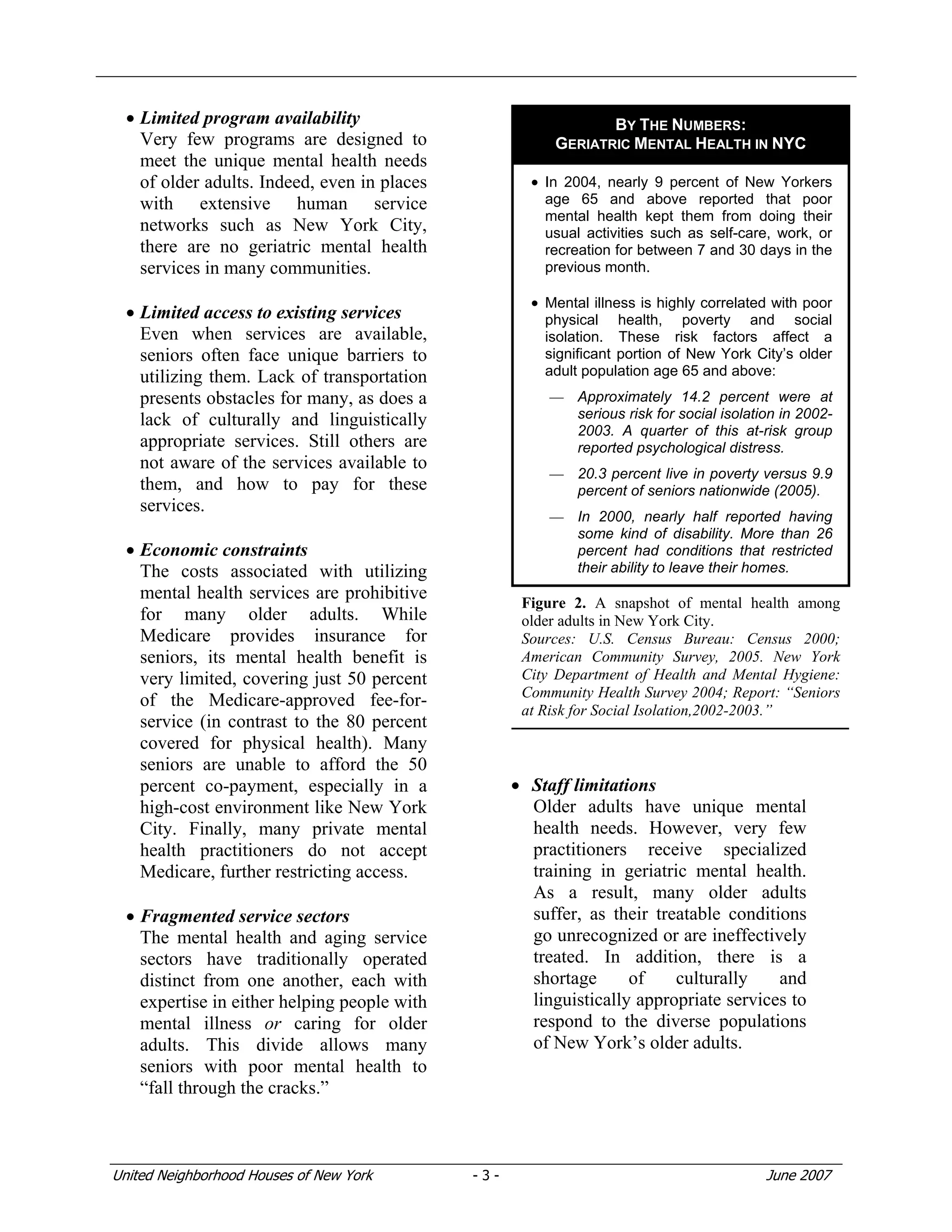

This document summarizes a report on meeting the mental health needs of older adults. It discusses the barriers older adults face in accessing mental health services and an emerging approach centered around expanding care options, community-based services, and integrating mental health and aging services systems. Promising programs in New York City that reflect this approach include social adult day care, co-locating mental health services at senior centers, and depression screening pilots.