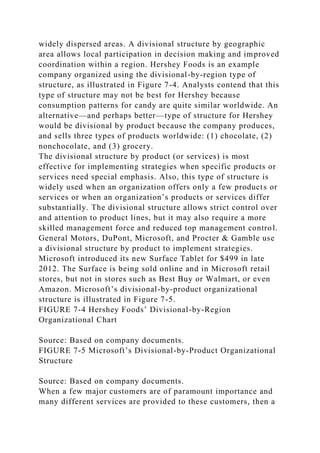

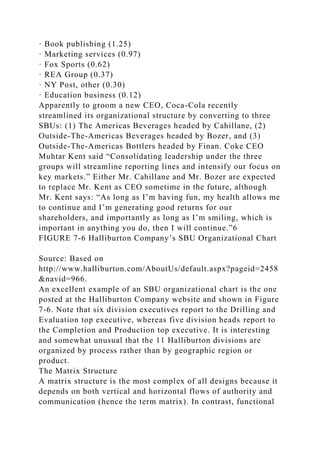

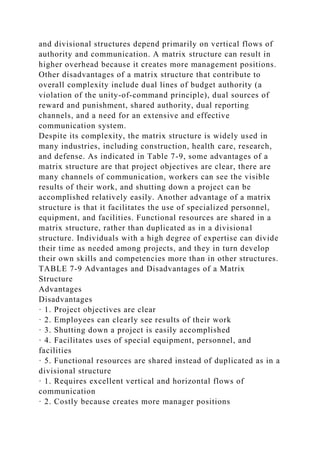

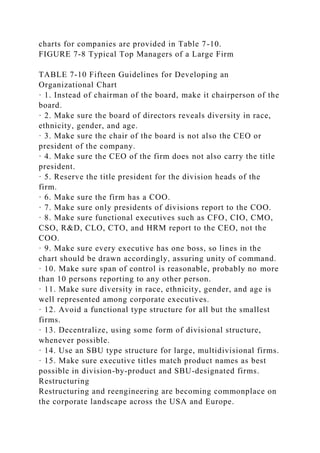

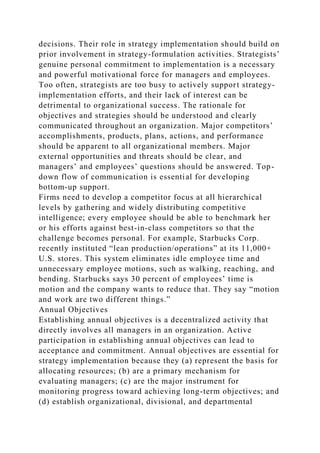

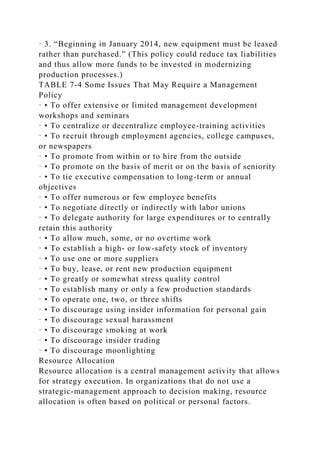

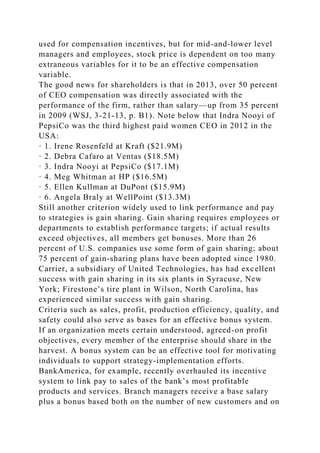

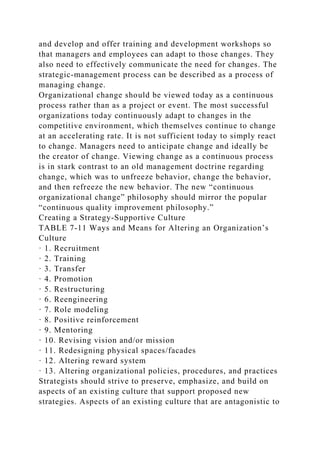

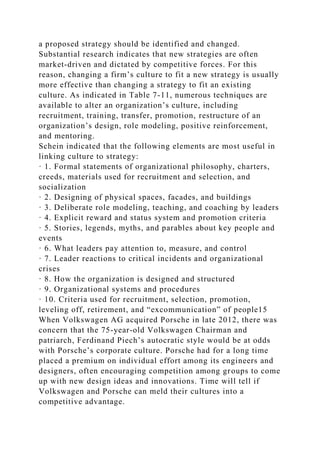

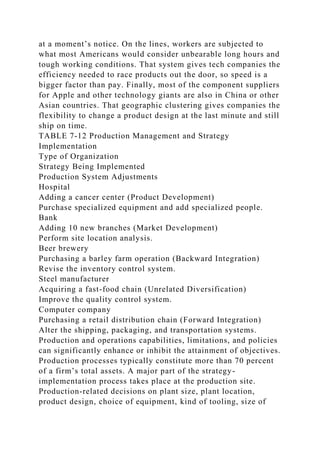

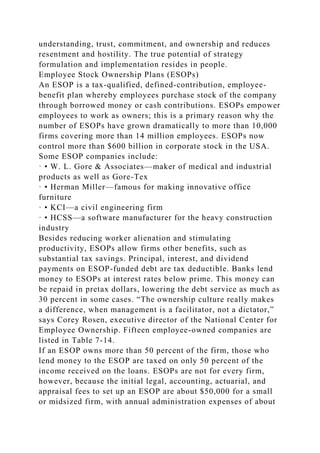

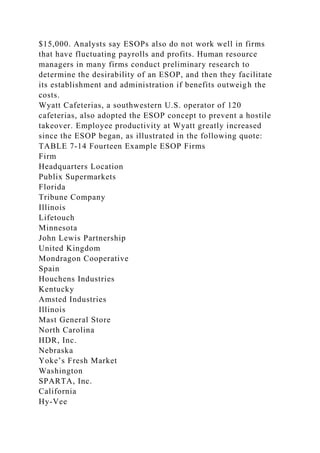

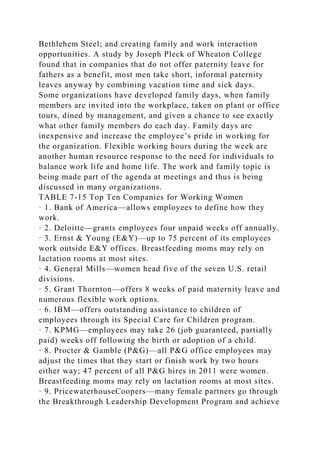

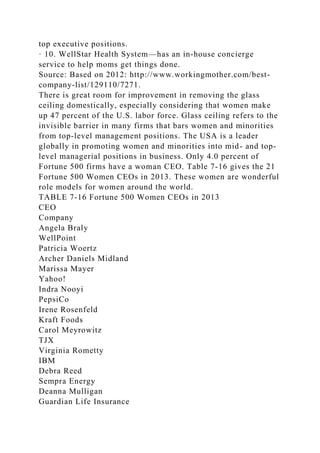

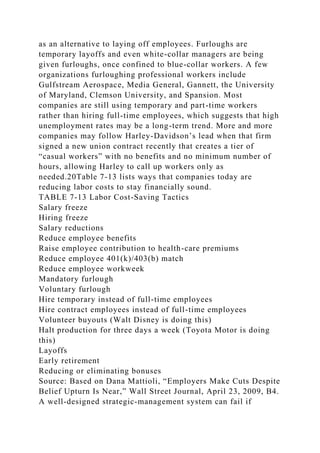

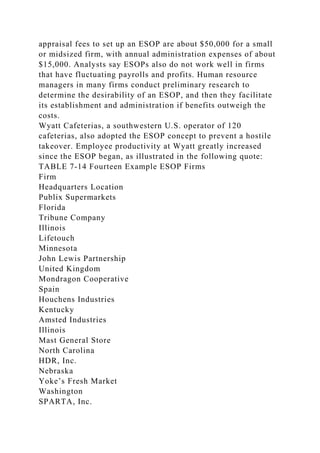

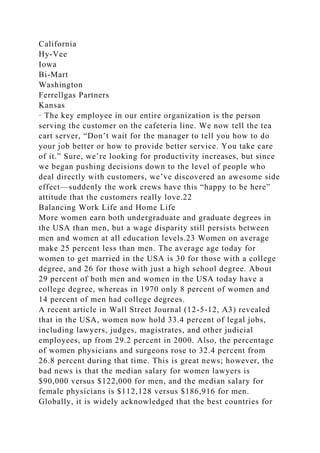

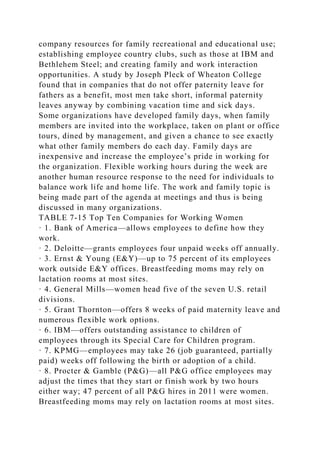

The document outlines strategies for effective management and operations, emphasizing the importance of organizational structure in strategy implementation. It discusses various structures such as functional, divisional, and matrix designs, highlighting their advantages and disadvantages in supporting business goals. The chapter aims to enhance understanding of how these structures influence employee commitment and performance in achieving strategic objectives.