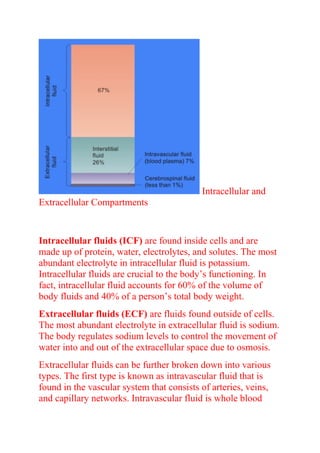

The document provides a comprehensive overview of fluids and electrolytes in medical surgical nursing, emphasizing the importance of homeostasis, the role of electrolytes in bodily functions, and factors influencing fluid and electrolyte balance. It covers aspects such as assessment, nursing interventions, diagnostic findings, fluid therapy, and the management of shock and infectious diseases. Understanding normal electrolyte ranges and their imbalances is crucial for nursing care to prevent serious health complications.