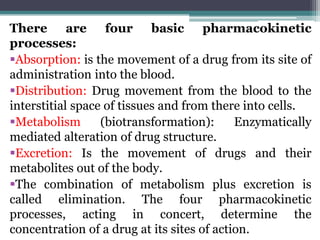

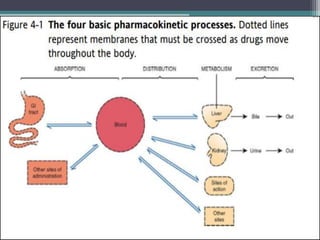

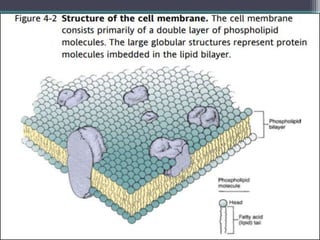

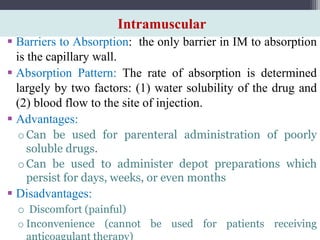

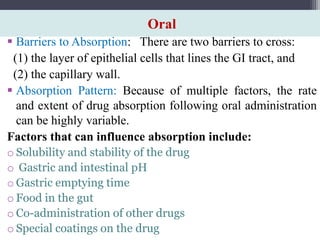

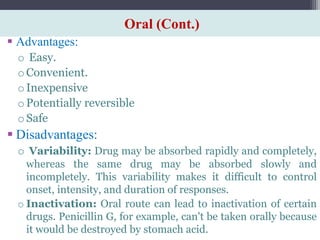

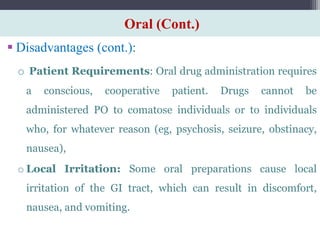

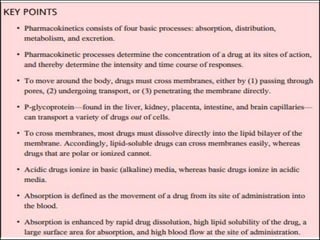

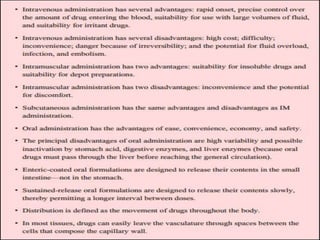

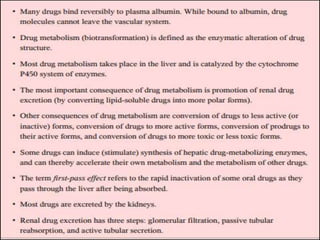

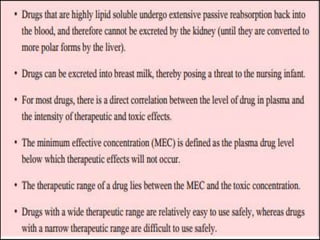

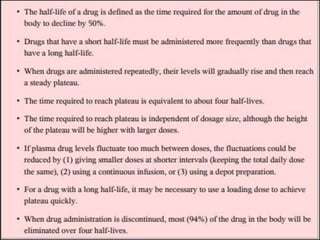

This document outlines key concepts in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. It discusses the 4 main processes that determine a drug's concentration over time in the body: absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Factors that influence each process are explained, such as how drug properties and route of administration impact absorption rate and extent. Common routes of administration like oral, intravenous, intramuscular are compared in terms of their advantages and disadvantages. The role of tissues, membranes, and drug properties in determining distribution is also covered.