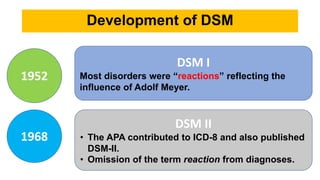

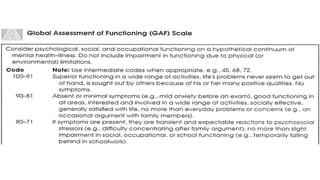

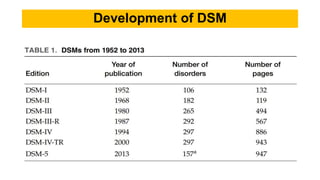

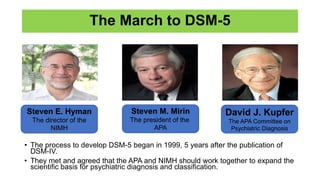

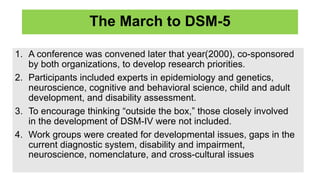

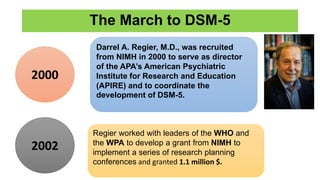

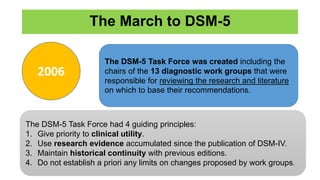

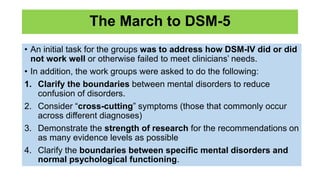

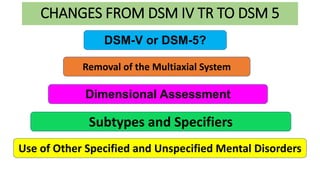

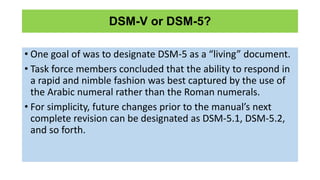

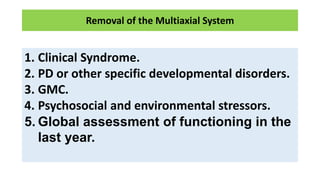

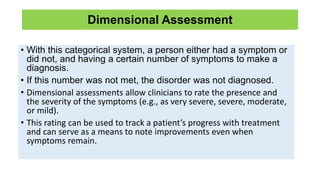

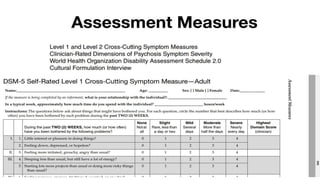

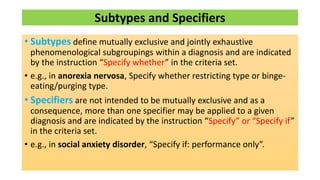

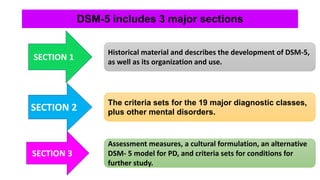

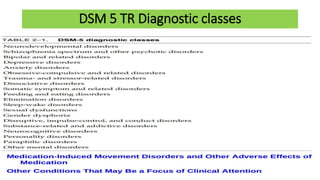

The document provides an overview of the development of the DSM diagnostic system from its origins in the 1920s to the current DSM-5. It discusses the key editions including DSM-I in 1952, DSM-II in 1968, DSM-III in 1980 which introduced a more empirical and reliable approach, and DSM-IV in 1994. It then summarizes the process of developing DSM-5 from 1999 to 2013, which placed greater emphasis on research and dimensional assessments. The document outlines some of the major changes between DSM-IV and DSM-5, including removing the multiaxial system, incorporating dimensional assessments, and revising subtypes and specifiers.