This master's thesis explores students' ability to recognize and use pseudo-intransitive verbs in English sentences. Pseudo-intransitive verbs can be used as both transitive and intransitive verbs. The study aims to test if Serbian high school students who learned transitive and intransitive verbs in elementary school can identify pseudo-intransitive verbs. A survey was administered to third-year high school students to analyze their understanding of verb types and ability to use pseudo-intransitives. The results will indicate if pseudo-intransitives should be included in the English curriculum in Serbian schools.

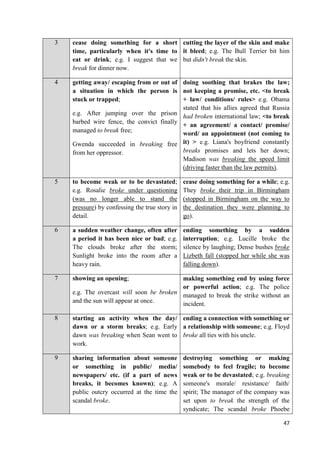

![7

M.A.K. Halliday based Systemic Functional Grammar by elaborating the works

created by his teacher J. R. Firth and the Prague school (a group of eminent linguists of the

early 20th

century). By exploring the purpose of a language, Halliday came to a conclusion

that text which is a product of written or oral communication refers to a language by means

that a person that speaks that language understands its message.6

The prior focus of Systemic

Functional Grammar is functional description and interpretation of a language, i.e. the usage

of a language. SFG provides useful interpretations of grammatical structures in terms of

different kinds of meaning, and has a well worked out model of language and context.7

Being

inspired by Louis Hjelmslev, Halliday sees text as a process that is defined as a part of system

of transitivity where: subject (noun) is described as participant – actor, agent and patient;

verb as process – action or state; prepositional phrase as circumstance – location; object

(noun) as participant - goal and patient; adjective as attribute – feature; etc.8

Therefore, according to the SFG terms, clauses that possess two participants - actor

and goal - are transitive clauses; and on the other hand, clauses that possess just one

participant - actor - are intransitive ones.9

Those clauses in which “someone does something“

and that are probed by asking “what did x do?“ are considered to be intransitive or middle. On

the contrary, clauses in which “someone does something and the doing involves another

entity“ are transitive. These clauses are probed by asking “what did x do to y?“10

In transitive

clauses, action is performed by an agent that acts deliberately being followed by a patient

who undergoes a change of state, or is affected in a precisely manner.

The verbs that are listed in dictionaries as transitive, such as: “decipher, depress,

stimulate”, are normally followed by direct object Complements (Cdo). Furthermore, verbs

labeled in the dictionary as intransitive tend to occur without an object Complement. There is

a problem if one tries to give a neat account of all this. The problem is that majority of verbs

in English (but not all) appear to be able to function both transitively and intransitively, or in

other words, with or without a Complement. For instance: in the following extract Cdo is

presented in italics in both a and b sentences:

a. […] some nerves stimulate an organ and others depress it;

b. […] some drugs stimulate while others depress.

(as we can see there is no Cdo in the sentence b.)11

6

Halliday M.A.K., Hasan, R.: Cohesion in English, Longman, London, 1976, Chapter 1; Halliday M.A.K:

Spoken and Written Language. Geelong, Vic: Deakin University Press, 1985.

7

Jones, H. Rodney and Lock, Graham: Functional grammar in the EFL classroom, PALGRAVE

MACMILLAN, 2011, P. 7

8

Matthiessen, M. I. M. Christian, Painter, Clare: Working with Functional Grammar: A Workbook, Arnold, 1997

9

Lock, Graham: Functional English Grammar: An introduction for second language teachers, Cambridge

University Press, 1996, p. 74

10

Eggins, Suzanne: An Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics: 2nd edition, Continuum, New York –

London, 2004, p. 216

11

Bloor, Thomas and Bloor, Meriel: The Functional Analysis of English: A Hallidayan Approach: second

edition, London: Distributed in United States of America by Oxford University Press Inc., New York, Arnold: A

member of the Hodder Headline Group, 2004, p. 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b5658d90-9c53-4d53-b715-309acc432e54-150810160532-lva1-app6891/85/1-12-320.jpg)

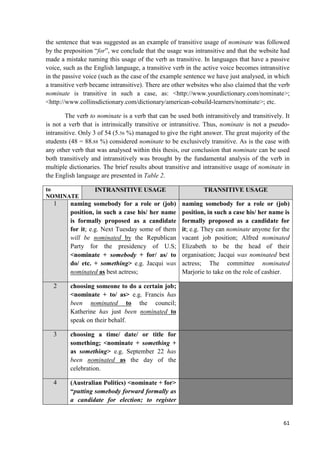

![8

Transitive and intransitive verbs according to SFG terms in clauses are presented in

the table below12

:

Actor and Process [intransitive] Action optionally extended to a Goal [transitive]

the troops attacked the troops attacked the capital

the guerillas hunted the guerillas hunted the militia

Glen kicked Glen kicked the ball

Advantages of Systemic Functional Grammar over traditional grammar:

- it includes the better part of the scope of linguistic;

- processing of a content includes context of a content as well;

- reliably interpret connection between grammar and experience of reality;

- it simultaneously deals with different linguistic functions; etc.13

Systemic Functional Grammar expands the horizons in terms of grammar of the

English language that was not included in traditional grammar. This scientific field critically

explores and reviews previous data about grammar. Besides determining pseudo-intransitives,

that is the topic of this research, SFG has determined and expanded notions of many other

grammar properties in all fields within traditional grammar. The following subchapter

describes characteristics of pseudo-intransitives.

2.1.3. PSEUDO-INTRANSITIVES

Regarding that these verbs are not the part of traditional grammar and that the majority

of educated people do not know of existence of such verbs, this research explored all existing

definitions and properties about this class of verbs. The aim is to develop a crystal clear

picture about these verbs.

We will start from the term pseudo-intransitives itself. The prefix “pseudo“ in pseudo-

intransitives derives from the Greek language. The actual translation of the Greek word

(ψευδής) is “false, lying, untrue“. It is used to label something that is false, fraudulent, or

pretending to be what is not.

12

J. R. Martin, Cristian M.I.M Matthiessen, Painter Clare, Working with Functional Grammar, Arnold, London,

1997, p. 122

13

Halliday M.A.K., Hasan Ruqaiya: Language, context and text: a social semiotic perspective, Oxford

University Press, USA, 1989; Halliday M.A.K., Matthiessen Christian M.I.M.: Construing Experience through

Meaning: A Language-based Approach to Cognition, Cassell, London, 1999.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b5658d90-9c53-4d53-b715-309acc432e54-150810160532-lva1-app6891/85/1-13-320.jpg)