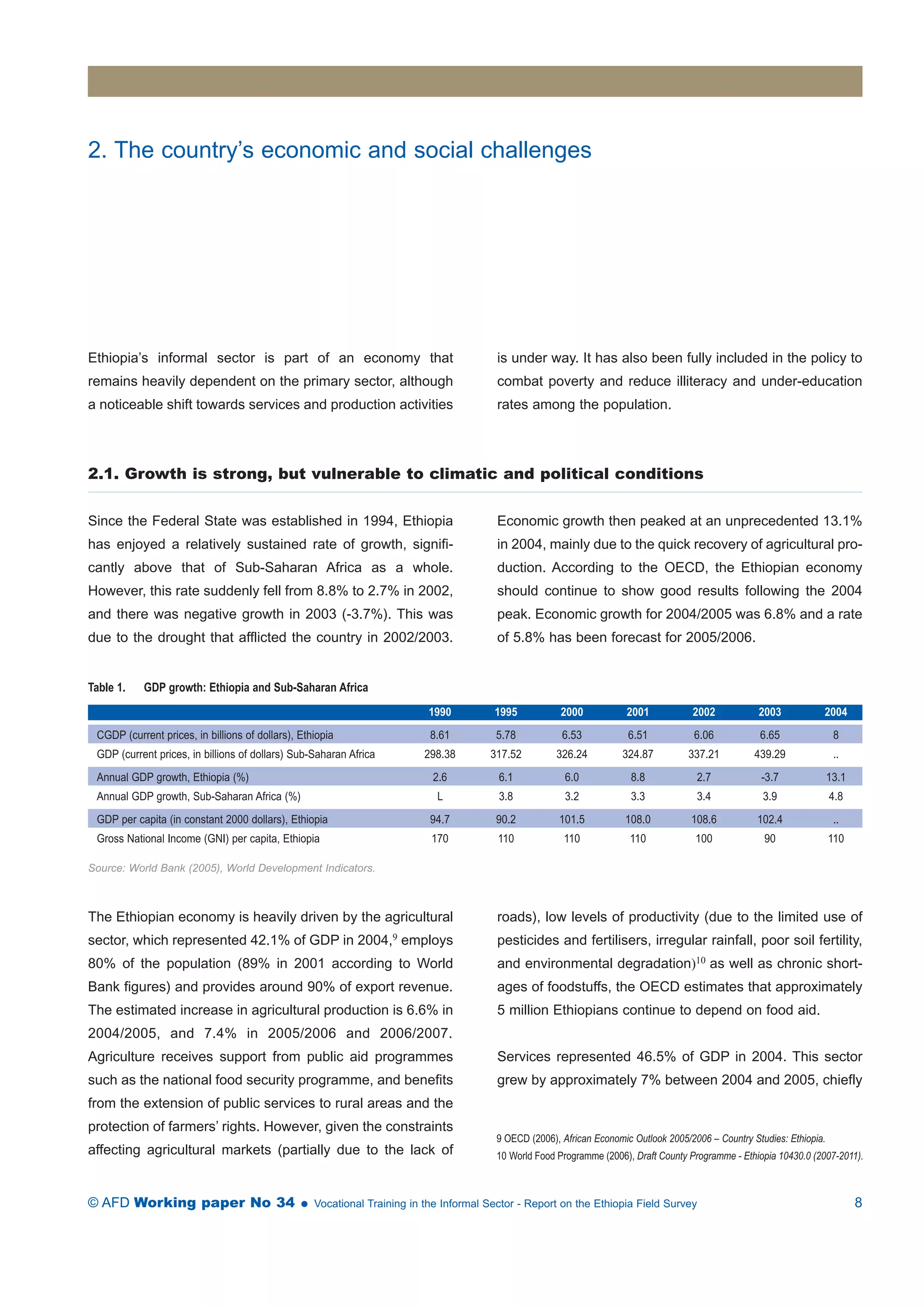

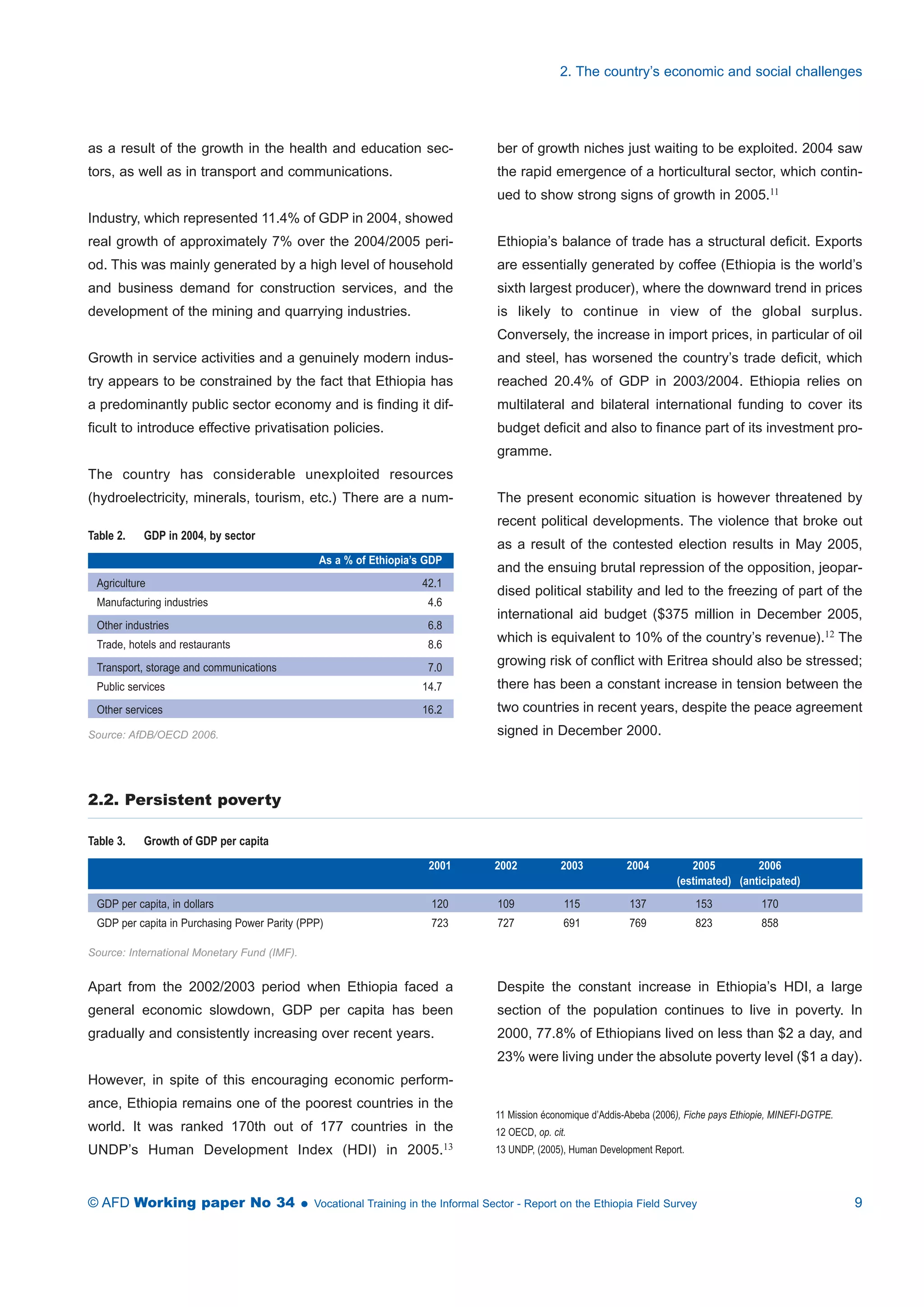

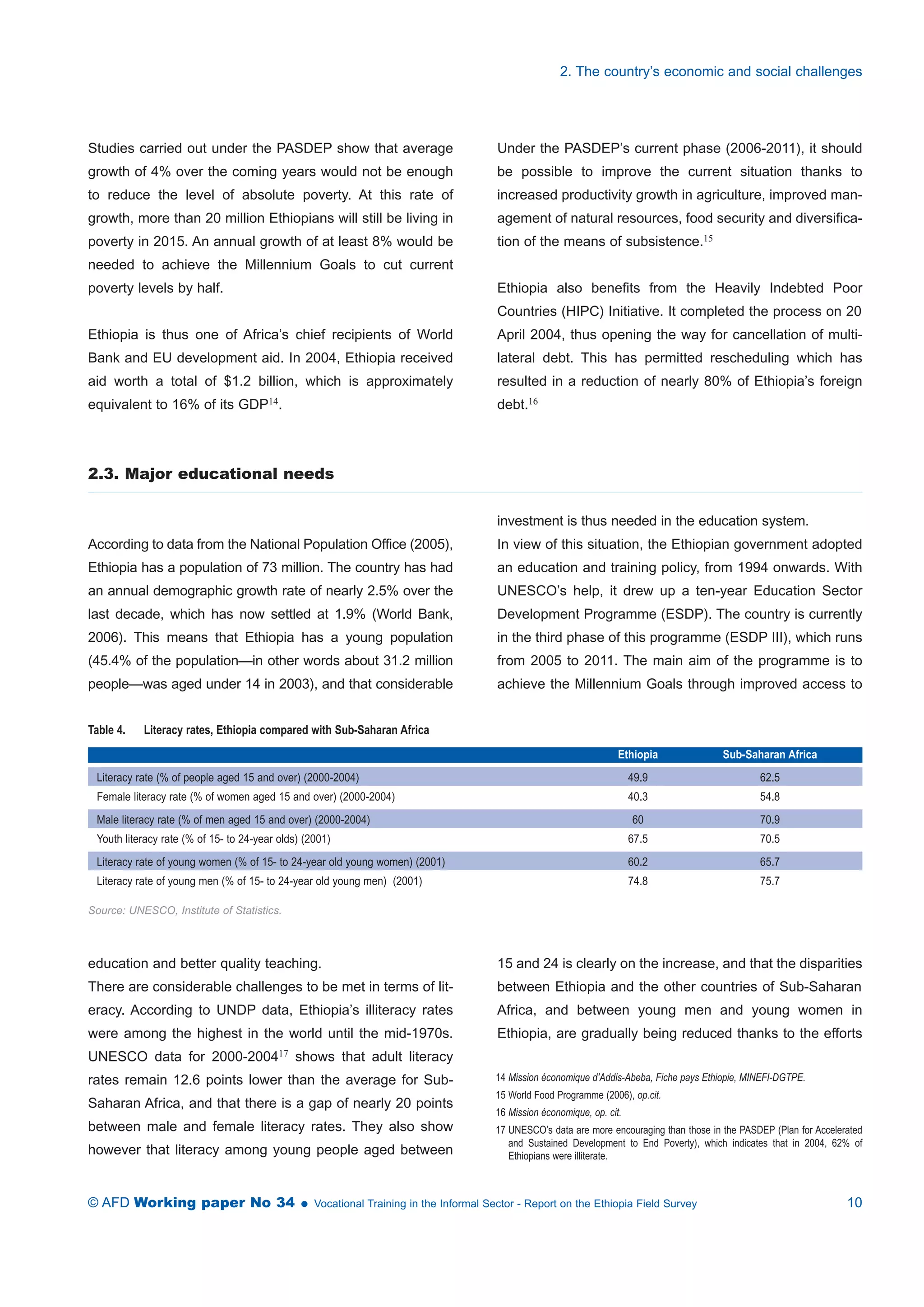

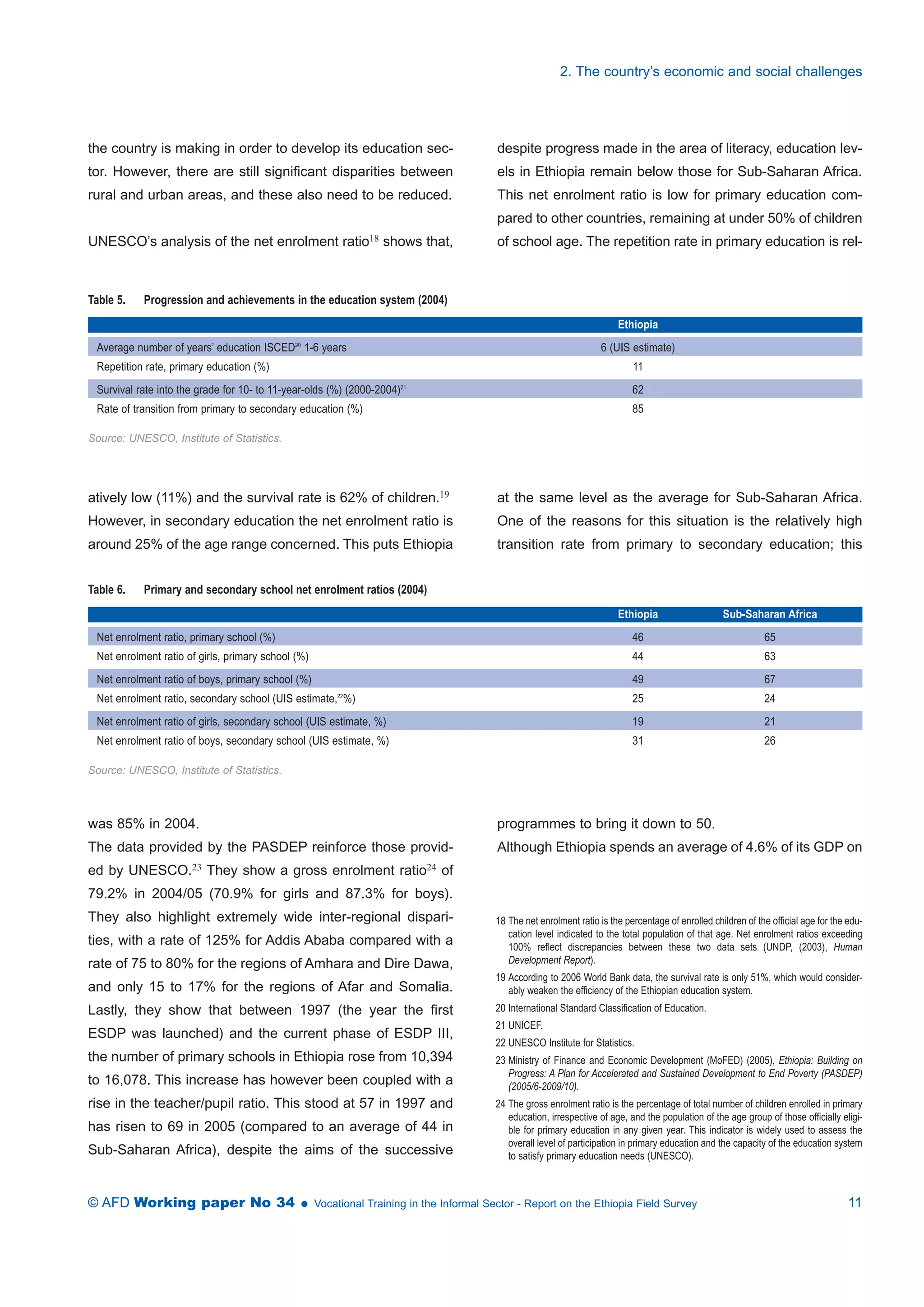

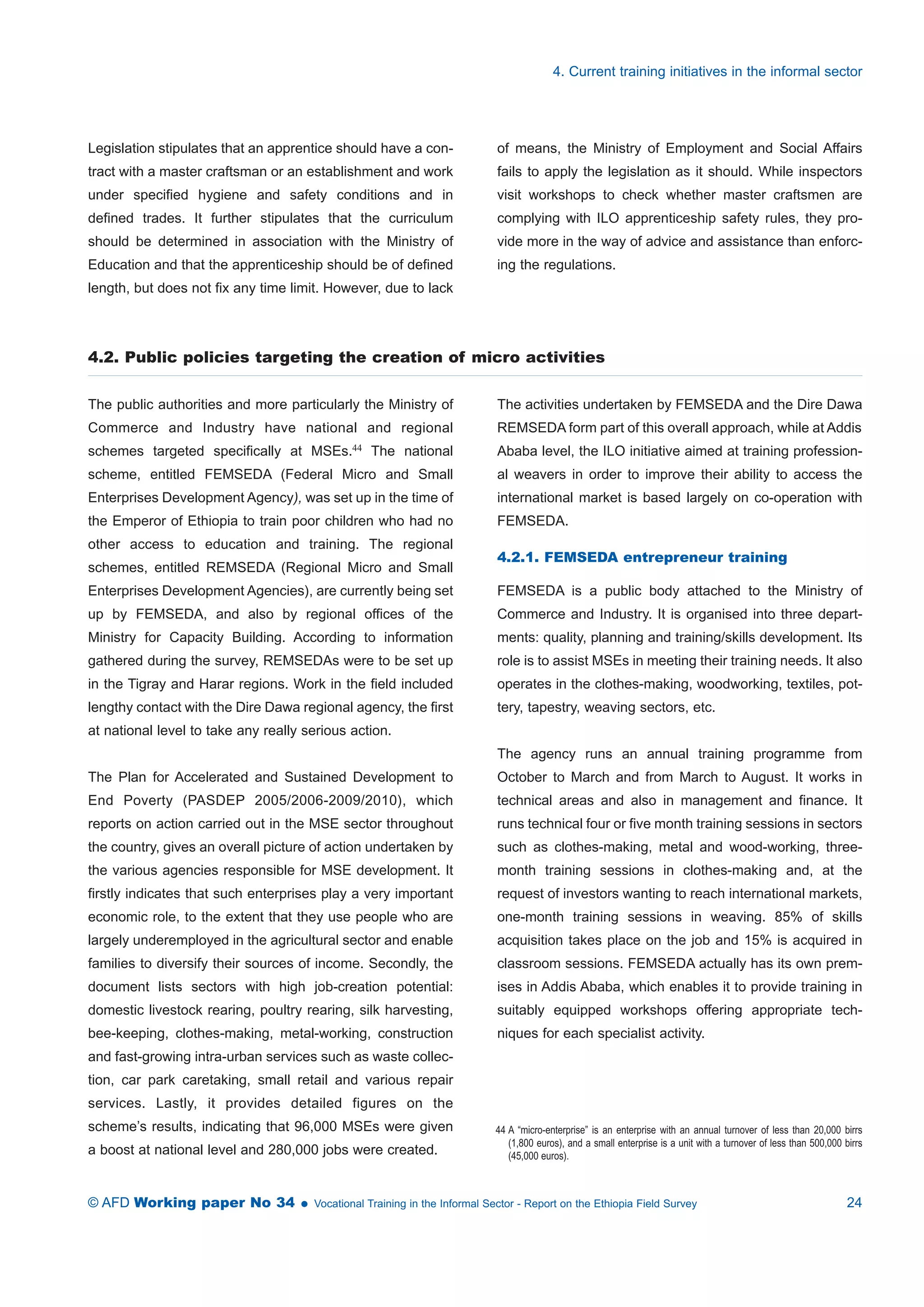

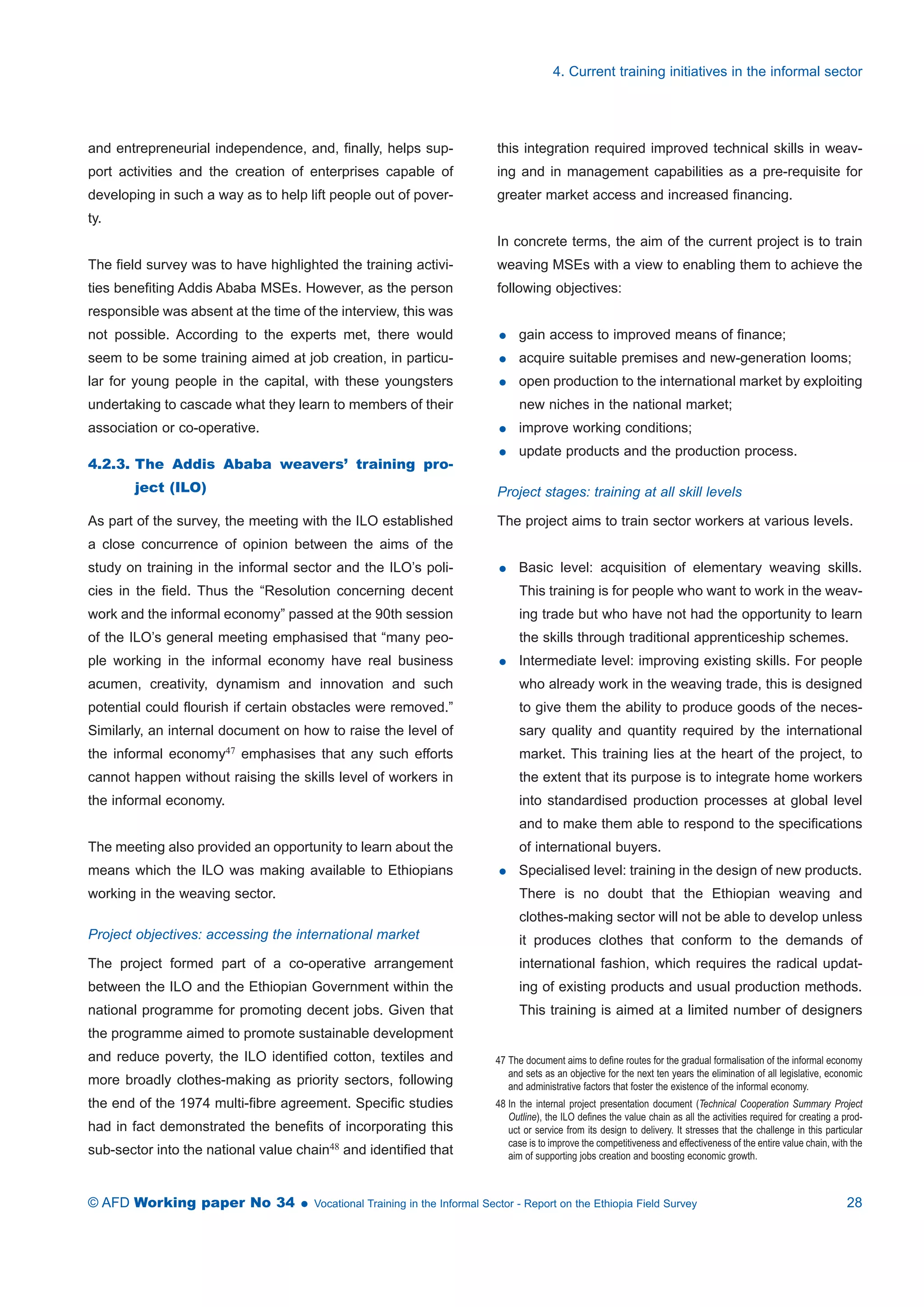

The document summarizes a field survey report on vocational training in Ethiopia's informal sector. It notes that Ethiopia is undertaking an ambitious reform of its education and training system to better respond to economic needs and integrate formal, non-formal and informal training. However, fully including the informal sector is challenging as officials have differing views of its size and role. The reform aims to establish centers that recognize skills from various sources, but must first acknowledge realities of the informal economy and involve existing stakeholders to be effective. While the reform offers opportunities, its success requires focusing on developing what already exists in the informal sector rather than just pursuing its own training agenda.