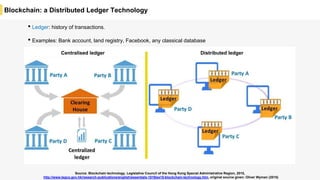

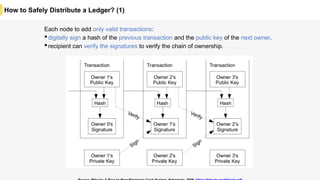

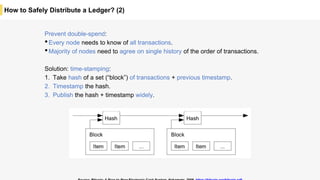

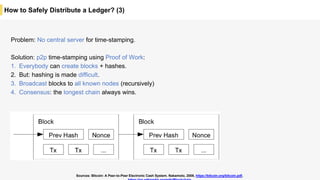

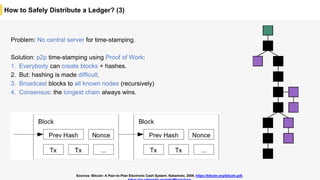

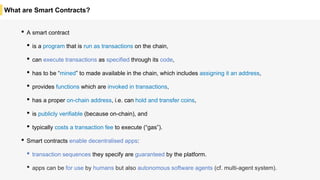

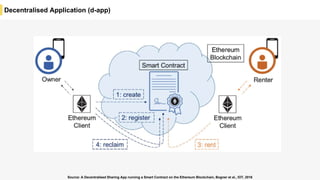

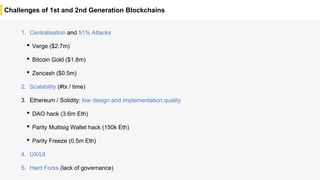

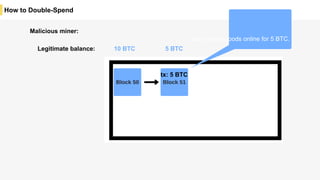

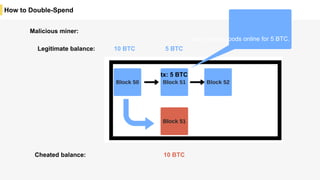

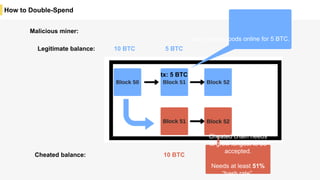

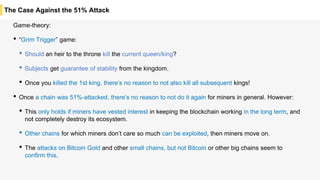

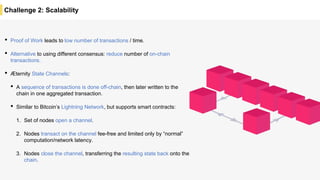

Blockchain is a distributed ledger technology that allows for the safe distribution of a ledger across multiple nodes. It works by having each transaction digitally signed and added in a "block" along with a proof of work. This prevents double spending and allows nodes to reach consensus on the transaction history without a centralized authority. Smart contracts enable decentralized applications to run transactions automatically according to the program. However, first generation blockchains face challenges around centralization, scalability, and smart contract quality. New solutions aim to address these through alternative consensus methods, off-chain transactions, and designed smart contract languages.