Summary of the article (50) Research problem and research ques.docx

- 1. Summary of the article (50%) Critical evaluation of article (50%) Below are some of the ways you can critically evaluate the article: (choose one) Criteria for quantitative paper: reliability, internal validity, construct validity, and external validity. (Required if doing a quantitative paper) Criteria for qualitative paper: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. (Required if doing a qualitative paper) World Development Vol. 39, No. 12, pp. 2119–2131, 2011 � 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 0305-750X/$ - see front matter www.elsevier.com/locate/worlddev doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.04.016 Local Means in Value Chain Ends: Dynamics of Product and Social Upgrading in Apparel Manufacturing in Guatemala and Colombia SETH PIPKIN *

- 2. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA Summary. — This paper contributes to existing discussions of global value chains (GVC) and industrial upgrading by examining obser- vations from eight months of field research in Guatemala and Colombia, where upgrading firms have their own nationally distinct form of labor relations, despite producing the same products for the same overseas buyers. Analysis of these observations leads to the con- clusion that labor relations show significant leeway in relation to upgrading outcomes, and that local history merits more attention as a driver of management strategy. The paper concludes with a discussion of relevant theory and implications for future research. � 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Key words — global value chains, industrial upgrading, apparel manufacturing, Guatemala, Colombia, Latin America * I would like to thank first and foremost Judith Tendler, Hugo Beteta, the MIT Program on Human Rights and Justice, and the Institute for Work and Employment Research (IWER) for allowing me to work in the field and develop this project. Thanks are also due to Michael Piore, Richard Locke, Susan Silbey, Suzanne Berger, Andrew Schrank, David Weil,

- 3. Alberto Fuentes, Regina Abrami, Ben Rissing, Matthew Amengual, Salo Coslovsky, Roberto Pires, participants in the IWER seminar at MIT Sloan, as well as the anonymous reviewers from World Development for all of their feedback and help. For all of the support received in this work, responsibility for errors is solely my own. Final revision accepted: March 1, 2011. 1. INTRODUCTION Policy paradigms for development have reached a cross- roads. The power of financial globalization to ‘eclipse’ the power of nation-states has been both asserted and questioned (Berger, 2000; Evans, 1997), while the Washington Consensus seems to have fully fallen out of favor (Held, 2005; Kucszynski & Williamson, 2003; Rodrik, 2006). The search for alternative models is palpable. Such a project may not be accomplishable in a stroke, or even in total, but whatever research is under- taken on development today seems to carry the burden of con- tributing to a timely, perhaps as yet unknown theoretical paradigm to how to create growth in the developing world. One literature that grapples with, despite predating, the transition out of the Washington Consensus is known as the global value chains (GVC) approach. This literature has exam- ined development on the micro- and meso-level of firm inter- actions in production processes distributed across regions and nations. Its focus has generally been on the distribution of power among firms within ‘value chains’ of international-

- 4. ized production and how these exchanges impact the develop- mental outcomes of global capitalist competition, especially in manufacturing. The GVC literature also describes a process of ‘upgrading’ by which firms participate in higher-value por- tions of the overall value chain structure. This paper attempts to build on that literature in two ways: first, by adding nuance to its central concept of ‘upgrading’ and second, by showing how this increased scope for variation may be driven by local politics and institutions. The case for such conceptual elaboration will be made with the use of field data collected by the author on apparel export- ers in Guatemala and Colombia. This data set, which com- prises fourteen successful ‘upgraded’ firms (seven in each country), constitutes a sample representative of the most ad- vanced apparel exporters in Guatemala and Colombia. While these firms often produced the same goods for the same gen- eral pool of largely American buyers, they nevertheless achieved their enhanced competitiveness by increasing value added 1 through industrial relations systems that varied signif- icantly on the national level. In Guatemala, upgraders made paternalistic investments in the production workforce beyond 2119 all minimum standards to enhance their firms’ ability to turn out garments of very subtle design both quickly and in quan- tity. In Colombia, the same goal was reached by combining Taylorist production floor management with departments of specially hired fashion designers. Whether one works on the production floor in one system or the other implies signifi- cantly different impacts, both in terms of skill and distribu- tions of firm-level surplus. Three main factors—foreign trade relations, timing of the apparel export sector’s emergence within the context of development agendas, and differing na- tional patterns of socialization of business elites—show dis- tinct promise in accounting for the observed variation. This leads to the suggestion that future research on the develop-

- 5. mental impacts of value chain upgrading must take into thor- ough consideration local appropriations of market signals, particularly in terms of how the attention, priorities, and, therefore, efforts of managers are trained by locally idiosyn- cratic institutional influences. To tell this story, a review of the GVC literature will clarify how the findings of this paper suggest ‘room to maneuver’ in the relationship between a product’s value-added and working conditions, as well as how such variability relates in these cases to local history. After this, section three consists of a brief overview of the global dynamics of apparel commodity chains, with attention to Guatemala and Colombia’s capabilities and niches within that larger field. Section four details the different forms of upgrading observed through fieldwork in both coun- tries, with a focus on cases of individual firms and the partic- http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.04.016 2120 WORLD DEVELOPMENT ular practices that are constitutive of their ‘upgrading.’ In sec- tion five, differences in historical and institutional variables in the two countries will be discussed to illustrate why local his- tory seems to relate more closely to firms’ choices than do the standard explanations of the value chain literature. The final section will consider theoretical as well as practical implica- tions of this research. 2. GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS—RECENT FINDINGS AND THEORETICAL CONSTRAINTS Having proliferated now for nearly 20 years, work in the global value chains literature applies a flip-side version of Wal- lerstein’s world systems analysis to case studies of the various paths along which commodities travel on their route from raw materials to point of consumption (Bair, 2005; Wallerstein,

- 6. 1995). That is, following from the prompts of world systems analysis, it focuses on the distribution of power between firms on the same ‘commodity’ or ‘value chain,’ usually at the level of local ‘clusters’ of industrial production, which roughly par- allels the French concept of the filiére (Raikes, Jensen, & Pon- te, 2000). The ‘flipping’ occurs when, instead of placing developing countries in a largely agency-less scenario of the world system’s imposed core-periphery economic hierarchy, GVC authors conceptualize these global production chains as spaces in which actors can savvily jockey for position to achieve varying degrees of success in ‘moving up,’ or as the lit- erature puts it, ‘upgrading.’ The overall GVC literature has been ably summarized elsewhere (e.g., Bair, 2005; Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002; Ponte, 2002), but it is worth noting how the approach boils down to a few key elements of analysis. First, insofar as the GVC literature tackles the phenomenon of globalized production, a key analytical insight is that this “new” division of labor creates new imbalances, risks and opportunities for firms and their employees. As such, this lit- erature presumes that there will be various power asymmetries along the value chain, with the most important and com- monly-cited being the dynamic of the “buyer-driven” chain. According to Gereffi, in a ‘buyer-driven’ value chain, 2 buyers as lead firms will “undertake the functional integration and coordination of internationally dispersed activities” (Gereffi, 1999 p. 41), 3 leading to the conclusion that the key to upgrad- ing is for non-lead firms in developing countries to actively pursue “different kinds of buyer-seller links” (ibid. p.40) whose variety will ostensibly lead to a higher accumulation of firm capacities and thereby competitiveness. In this general context of asymmetry, “governance” emerges as another concept of primary importance. It is invoked in various ways to describe the rules by which Gereffi’s “integra- tion and coordination” take place. Gibbon, Bair, and Ponte

- 7. (2008) established a typology of approaches to governance, labeling Gereffi’s earlier approach to buyer-driven chains a “driving” approach. A second category, called “coordinating,” stems from the work of Gereffi et al. (2005), which employed transaction cost economics to focus on upgrading as a phe- nomenon best understood through the lens of commodity characteristics and a dyadic level of analysis. The third cate- gory offered is a “normalization” approach, in which the the- oretical lenses of French Conventionalism (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006), an approach to analyzing how mental mod- els of justification govern economic decisions, as well as Fou- cault’s approach to power via “governmentality” as a set of hegemonic assumptions (Foucault, Burchell, Gordon, & Mill- er, 1991), are seen as the key perspectives on upgrading as an outcome primarily of dominant discourses of scientific exper- tise, “best practices” and international standards. This distinc- tion is pertinent to this paper particularly insofar as norms and conventions appear to have quite a bit to do with the observed differences in approaches to upgrading, albeit while illustrating how a given GVC governance structure may in fact permit multiple “invoked models of practice” (Gibbon & Ponte, 2008) among its suppliers, provided the lead firm’s logistical needs are met. The processes of “buyer succession” and establishing gover- nance rules are key to the desired outcome from which GVC draws its main claim to relevance to practitioners of economic development: “upgrading.” Perhaps because of an inherent difficulty in combining market measures with broader con- cepts of power, upgrading is generally viewed as the most vex- ing concept in the literature (see e.g., Dussel Peters, 2008; Morrison et al., 2008). It has been defined by Gereffi as a mix of profitability and capital-/skill-intensity (Gereffi, 1999), by Humphrey and Schmitz as movements or changes in something like a “5 W’s” of the commodity (process, prod- uct, function, multi-chain) (Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002), and

- 8. by a variety of others as simply unit price (Gereffi & Kor- zeniewicz, 1994; Schrank, 2004). Given the ambiguity and lack of consensus in the literature, I will offer a sample of firms that qualify in ways most repeatedly delineated by the literature (non-basic goods, enhanced logistical capacity) as having ‘up- graded.’ Regardless of the mechanism at play, GVC research is fre- quently constrained by the assumption that to upgrade, sup- pliers without market power must learn directly from their advanced-country buyers. This tendency appears frequently in the individual case studies that populate the GVC literature. Whether in light manufactures and agricultural exports in La- tin America and East Asia (Bair & Gereffi, 2001; Gereffi, 1999; Giuliani, Pietrobelli, & Rabellotti, 2005), or surgical instru- ments in Pakistan (Nadvi & Halder, 2005), the key variable is often the lead firm’s guiding hand in upgrading possibilities for developing-country suppliers. Thus even surprising cases of local collective action and innovation tend to appear as reactive, filling in voids left by capricious foreign buyers, as was apparently the case of the Sinos Valley footwear cluster in Brazil (Bazan & Navas-Aleman, 2004). The literature is not without examples of local contingencies complicating what might be called “buyer/product determin- ism.” A variety of recent publications have made mention of local historical legacies and institutions as influencing upgrad- ing outcomes (Gellert, 2003; Neidik & Gereffi, 2006; Pickles et al., 2006; Rothstein, 2005; Thomsen, 2007). In each case, a locally unique array of interests and resources led to devel- opmental outcomes not predictable by the buyer- or seller-dri- ven tendencies of the particular commodities being produced. Yet these examples have yet to seriously impact the theoretical model of GVC, and reviews of the literature reveal a need for further examination (Bair, 2005, 2008).

- 9. Concomitant with the tendency to conflate the back-and- forth of communicating and responding to buyer demand with all value chain activity is the tendency to leave firm-le- vel outcomes and developmental impacts (in terms of im- pacts on workers) undifferentiated. Yet past research shows that it is not enough to characterize the choice of firms as one between one where workers and employers win and a low road where both lose (Knauss, 1998). Usu- ally, if these issues are mentioned at all, they are noted as a lacuna in the GVC approach (Plankey Videla, 2005). This marks a second contribution of this paper: to contribute to the project of observing differential distributions of benefits from value chains (Kaplinsky, 2001) by connecting workplace LOCAL MEANS IN VALUE CHAIN ENDS 2121 results to firm learning as a process embedded in local institu- tional and political history. Of special note in the advancement of the above themes in relation to apparel are works by Lane and Probert (2009), Te- wari (2008), and Gibbon and Ponte (2009). These works show in a very detailed manner the importance of national and local institutions and development paradigms in structuring firms’ approaches to a given GVC governance system. This paper aims to contribute to the shared project of these works by focusing not only on national influences on value chain com- petition, but more specifically, on cases where the outcomes as regards buyers are controlled for but nonetheless the inter- nal production organizations diverge substantially. 3. THE APPAREL COMMODITY CHAIN (a) Characteristics salient to a development research agenda The apparel sector warrants continued development re-

- 10. search for at least two main reasons, increasing diffusion and local capacity building in developmental state-private sector relations. Regarding diffusion, apparel is an industry where less-developed nations’ portion of supply continues to grow. Since its early outsourcing after World War II (Rosen, 2002), apparel imports to the United States have ballooned to account for 60% of all domestic consumption (WTO, 2001) while continuing to expand into ever more sophisticated product niches (Tokatli, 2008). Cautioning against some opti- mists are observations that Latin American firms especially are considered to be a different story from the East Asian “full-package” and “Original Brand Manufacturer (OBM)” firms (Gereffi, 1999), having been cited as exhibiting a “false competitiveness” due to their reliance on trade benefits and quotas, not to mention geographic proximity to the US (Abernathy, Volpe, & Weil, 2006; Mortimore, 2003). Nonethe- less, even many critics of apparel as an ostensible “develop- ment driver” recognize it as a site for potentially important state capacity-building (Amsden, 1994; Schrank, 2004), mak- ing any variations observed in the building of local know- how within Latin America especially important. (b) Regional performance and the positions of Guatemala and Colombia Guatemala and Colombia’s apparel exporters have come from different pasts to relatively similar positions as exporters to the United States. In terms of size, Guatemala exports sig- nificantly more clothing to the United States, where almost 100% of all of its apparel exports are destined. As of July 2008, Guatemala’s apparel export sector comprised approxi- mately 114 firms and 68,444 workers (VESTEX, 2007). In Colombia, because firms commonly practice a mix of domestic and export production, perhaps one-third of its 80,000 apparel workers are producing output for the US, which is still Colom- bia’s largest single export market (though insurgent demand

- 11. has brought Venezuela to approximately the same portion of exports in recent years) (ASCOLTEX, 2006; DANE, 2005). For both countries, apparel alone is an important component of manufacturing and GDP: in Guatemala, it accounts for approximately 20% of its manufacturing activity and approx- imately 2.5% of GDP (BANGUAT, 2006; UN, 2010), while in Colombia, it represents approximately 10% of manufacturing GDP and 1.6% of national GDP (Proexport, 2008). In terms of the legal structure and ownership of producers in each country, Guatemala has had an in-bond tariff law (Decreto 29–89) in place since 1989, which allows producers to import inputs and export assembled products without tar- iffs. Colombia has free trade zone rules and other related laws to facilitate similar light manufacturing activities (USITC, 2004). The primary difference between the two has been Gua- temala’s inclusion in preferential trade agreements with the US, a key factor whose impact will be discussed further be- low. In Guatemala, a little less than 60% of apparel exporters are Korean-owned and operated (VESTEX, 2010). No such pat- tern exists in Colombia, where the legacy of this sector is far more domestically rooted. There is a vast literature on the importance of capital origins for development outcomes, par- ticularly on the tendency toward enclave economies (Amsden, 2001; Dos Santos, 1970 ch.5, Gallagher & Zarsky, 2007), and certainly such effects are to be observed in Guatemala, partic- ularly insofar as the country’s early closures after the end of the MFA quotas had even a higher proportion of Korean firms than was represented in the overall population (VES- TEX, 2005a); however, as will be discussed further below, the influence of Korean-owned maquiladoras has also been a significant resource in the learning processes of the most high-performing firms in the sector, some of which have in turn influenced many of the Korean firms themselves. As such,

- 12. their influence has not been fully typical of the enclave model. In terms of context for labor relations and unions, the coun- tries are considered by many as consistently two of the most highly labor-repressive states in the western hemisphere (ITUC, 2009). Since a period of “annihilation” largely at the hands of Guatemalan business elites and elements of the mil- itary in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Guatemalan unions have had extreme difficulties in developing coherent ap- proaches to organizing or workplace standards (Levenson- Estrada, 1994, p. 173, Fuentes, 1998). The Colombian policy scene, meanwhile, focuses far more of its labor policy toward “flexibilization” than strengthening unions, with little appar- ent change effected on this by the country’s efforts toward a free trade agreement with the United States (Lopez, 2009). And while the preferential trade relations that Guatemala has had with the US have provided an outlet for transnational activism in support of improved labor standards (Frundt, 1998), the impacts of these outside pressures on labor condi- tions in Guatemala have been spotty, ephemeral, and highly dependent upon how domestic interest groups contest reform and enforcement issues (Fuentes, 2007). In sum, as regards im- pulses driving the observed upgrading, and in particular, so- cial upgrading above minimum labor standards, little of it derives in any immediate way from national labor enforce- ment, unions, or transnational activism. Regarding what goods are exported and level of specializa- tion, the two countries are fairly similar. Tables 1A–1D illus- trate several important trends: first, in Guatemala, an increase in the value of goods exported to the US, as well as a hugely expanding apparel production base overall. By 2004, 4 Guate- mala’s highest-value item in its top five exports was men’s and boys’ cotton trousers, breeches, and shorts, a category largely comprised by denim jeans. Colombia shows both similarities and differences: its apparel sector in 1989 was much more

- 13. diversified than Guatemala’s, and to a degree remained so in 2004 (though both countries consolidated more towards their top export categories). Like Guatemala, Colombia has become a major exporter of casual pants and shirts for both genders to the United States, though Colombia has carved out a deeper niche in higher-fashion items such as men’s suits and women’s underwear and swimwear, with suits in particular a long-term specialty for Colombia (Morawetz, 1981). As we will see Table 1A. Top 5 Guatemalan apparel exports to the US, 1989 Product category Value exported to US Rank in Colombia’s top exports Rank as exporter to US Price per unita Percent total value of apparel exports to US 1. 348—W/G cotton trousers/slacks/shorts $28,637,452 1 13 $41.8 20.0 2. 347—M/B cotton trousers/breeches/shorts $23,154,763 4 12 $39.8 16.2 3. 340—M/B cotton shirts, not knit $11,729,009 5 21 $49.5 8.2 4. 359—Other cotton apparel (e.g., vests, swimwear, ties, overalls)b $ 6,139,824 32 12 $14.2 4.3 5. 339—W/G cotton knit shirts & blouses $ 4,823,937 3 33

- 14. $27.6 3.4 Total 52.1 a Units are 1 dozen unless otherwise indicated. b 1 unit = 1 kg. Table 1B. Top 5 Colombian apparel exports to the US, 1989 Product category Value exported to US Rank in Guatemala’s top exports Rank as exporter to US Price per unit Percent total value of apparel exports to US 1. 348—W/G cotton trousers/slacks/shorts $23,977,902 1 18 $67.6 15.2 2. 641—W/G man-made fabric not knit shirts & blouses $8,091,337 7 16 $98.5 5.1 3. 339—W/G cotton knit shirts & blouses $7,803,542 5 30 $29.2 5.0 4. 347—M/B cotton trousers/breeches/shorts $6,309,075 2 24 $49.6 4.0 5. 340—M/B cotton shirts, not knit $6,204,803 3 27 $55.5 3.9

- 15. Total 33.2 Table 1C. Top 5 Guatemalan apparel exports to the US, 2004 Product category Value exported to US Rank in Colombia’s top exports Rank as exporter to US Price per unit Percent total value of apparel exports to US 1. 339—W/G cotton knit shirts & blouses $729,630,106 12 1 $32.2 37.2 2. 348—W/G cotton trousers/slacks/shorts $248,372,231 2 5 $62.4 12.7 3. 338—M/B cotton knit shirts $216,923,956 3 8 $35.3 11.1 4. 347—M/B cotton trousers/breeches/shorts $164,547,320 1 5 $88.5 8.4 5. 648—W/G man-made fabric slacks/breeches/shorts $119,439,699 20 5 $46.5 6.1 Total 75.5 Table 1D. Top 5 Colombian apparel exports to the US, 2004 Product category Value exported to US Rank in Guatemala’s

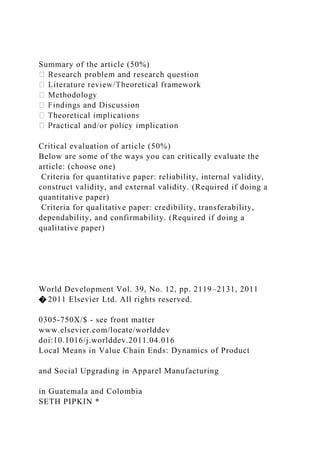

- 16. top exports Rank as exporter to US Price per unit Percent total value of apparel exports to US 1. 347—M/B cotton trousers/breeches/shorts $124,242,578 4 9 $82.1 19.5 2. 348—W/G cotton trousers/ slacks/shorts $87,934,302 1 25 $90.3 13.8 3. 338—M/B cotton knit shirts $39,321,330 3 30 $30.1 6.2 4. 433—M/B wool suit-type coats $33,138,539 33 4 $372.0 5.2 5. 352—Cotton underwear $32,862,782 26 22 $13.6 5.2 Total 49.9 2122 WORLD DEVELOPMENT below, these larger trends are mirrored in the population of upgraded firms in this paper’s sample. Given that the most important area in overlap for upgrad- ers between the two countries was found to be bluejeans, the reader can also refer to Figure 1 to see the comparability of Guatemala and Colombia vis-à-vis international competitors. These two countries clearly show a movement toward average higher price per unit than their Latin American peers, an interesting reversal given that Guatemala and Colombia were well below this regional average in 1989. This high perfor- mance, which is at most driven only in small part by local sourcing of materials, 5 suggests that these countries have suc- ceeded in carving out specialized product niches that many

- 17. regional competitors have not, reaching a level that resembles more the higher-on-the-chain Asian producers. Figure 1 also gives an example of how the repeal of the MFA in 2005 deliv- ered a shock to apparel prices, one that Guatemala and Colombia’s more specialized manufacturers have apparently managed to escape (though there have been impacts in volume). Figure 1. Mens and boys cotton trousers, breeches and shorts exported to the US, nominal US dollars. Source: OTEXA. LOCAL MEANS IN VALUE CHAIN ENDS 2123 Both Guatemala and Colombia are in similar respects ‘high achievers’ for their region; what they lack in volume output they both make up for in unexpectedly high unit prices, often on the exact same products. The discussion below of data gathered in the field shows that this has been achieved in each country through very different means. The remaining ques- tion, then, is what variables other than the good produced and factors specific to the lead firm on the chain might account for the different means by which firms have been observed to upgrade. 4. EMPIRICAL OBSERVATIONS OF DIFFERENCES IN UPGRADING (a) Methods The material described in the cases here originates from fieldwork performed by the author in 2005–06 in Guatemala, and 2007 in Colombia. Five months were spent in Guatemala across three visits, resulting in 68 interviews of 46 different individuals performed almost entirely in and around the cap- ital city, where over 90% of Guatemalan apparel export man- ufacturers are located (VESTEX, 2007). This work was

- 18. originally intended to serve as a standalone project, but the opportunity to study the same industry in Colombia emerged as an extension. Fieldwork in Colombia replicated the meth- ods utilized in Guatemala. In Colombia, observations were de- rived from 25 unique interviews performed over the summer of 2007, all taking place either in Bogotá or Medellı́n, Colom- bia’s two biggest cities, as well as its biggest sites for apparel and textile production. Interviews were semi-structured, usu- ally lasting from one to three hours. Respondents outside of firms included academics, employees of government ministries (including Ministries of Labor and Trade), employees of NGOs, USAID and the US State Department, union leaders, manufacturing workers, and directors and employees of busi- ness and trade associations. In Colombia, 9 of the 25 intervie- wees were not managers or employees of manufacturing firms, whereas in Guatemala, these various outsiders numbered 28 out of 46. Within firms, interviewees were usually either Gen- eral Managers or Directors of Production, but also sometimes included Directors of Human Resources and other upper-level management. General topics included basic factory character- istics (products, sources of capital, market niches), the dynam- ics of factory operations (including workforce characteristics), competitive and logistical challenges, and relationships with clients, suppliers, and governmental/other institutional actors. Firms interviewed in both countries were reached in one of two ways: by referral from multiple interviewees who could ex- plain why the firm was an example of upgrading, or by ran- dom phone call or meeting at a trade show, where the author attempted to attain a better sense of ‘median’ and sometimes smaller, more marginal firms in the sector. This al- lowed for a sample showing wide variation across producers from most to least advanced, while using principles of statisti- cally nonrepresentative stratified sampling (Trost, 1986) to get as deep as possible into variation among upgraders as the most advanced segment of the population.

- 19. In this paper, the cases of upgraders are all firms who have performed “product upgrading” in the sense of having moved past producing apparel basics. The forms of product upgrad- ing observed were often related to special finishes, washes and dyeing processes applied to garments, especially special chem- ical and manual processes applied to blue jeans (see Sec- tion 4d). Other forms of product upgrading included the use or even development of unique materials, such as wicking fab- rics for athletic use, very detailed embroidery work or addi- tional components (e.g., sequins) added to the basic garment, or the capacity to customize the images or words printed on a garment multiple times within one run of a gar- ment order. Some of these product upgrades would come in combinations, especially those involving washes/finishes/dyes and embroidery/specially added components. Furthermore, the upgraders discussed here demonstrate “process upgrading” insofar as they all offer some form of advanced efficiency or logistical management (whether in terms of full-package production, specialized inventory, “quick 2124 WORLD DEVELOPMENT turnaround” or “rapid replenishment” systems, or a combina- tion of these.) Insofar as “full package” involves a manufac- turer taking responsibility for sourcing and inventorying all components, as well as delivering to the buyer a finished garment that is ready to sell (Gereffi, 1999), all of the upgraders in this sample, with the exception of the Colombian garment- wash specialist Tecni-Lavados, qualify under that heading. These systems were all discussed during interviews, and were confirmed upon the researcher’s visit to the production floor. Almost any of the output of any one firm in the overall two-

- 20. country sample (with the possible exception of lingerie and men’s suits), stripped of any label of origin, could appear even to one knowledgeable in apparel manufacturing to have come from either country. To capture issues of power, influence, and sources of learn- ing, the interview process was used to capture firms’ reputa- tion, as measured by the opinions of outsiders such as buyer representatives/sourcing directors, employees of business asso- ciations, local and international scholars and government bureaucrats, and members of the local union, labor law, and/or non-government organization (NGO) community. Over the course of this research, if a preponderance of such outsiders described a company as “world-class,” illustrated how it is capable of competing with the most advanced Asian exporters, and/or cited unique practices that set a given firm apart from the general local population, this was considered reputational evidence of upgrading. However, if a firm, upon visit, did not show the basic product/process upgrading fea- tures described above, then it was not included in the sample. Thus, all of the upgraders in this sample produce beyond ba- sics, have established specialized logistical efficiencies, and have been described by outsiders with little or no incentive for promoting the company as showing extra-ordinary capa- bilities as compared with the local field of producers. In contrast to these traits, a non-upgrading firm would (a) produce only basic goods such as regular, cotton, unadorned tshirts, (b) require sourcing from a buyer (as opposed to oper- ating full-package), and (c) not display any significant func- tional or efficiency-related innovations, whether in logistical management or worker voice on the floor. There was strong consensus across all interviewees from all professional fields who the top ‘upgraders’ in the country were. In terms of inter- preting these findings, as Dion (1998) notes, these comparative observations are an appropriate dataset for the induction of

- 21. necessary conditions for value chain upgrading: as such, the lack of commonality in organizational strategies opens up fur- ther room in the literature for inquiry on the organizational antecedents of upgrading in garments. Furthermore, this paper offers a second set of inductions based on the interviews’ data on firm learning combined with secondary sources on related historical and institutional factors. Following these two points, the data offer a provocative null finding on upgrading choices (i.e., different organizational techniques offering equivalent market rewards), with induction of possible factors most influ- ential in the attention, priorities, and know-how of managers— namely, trade rules, local development priorities, and sites of management education and socialization. Table 2 outlines the salient observed characteristics of the fourteen upgraded firms in Guatemala and Colombia. Names of companies have been altered to preserve anonymity, which was required by internal review board rules and requested by many participants. (b) Upgrading firms in Guatemala In Guatemala, the key tendency among upgraders was to equate competitiveness with investments in the production floor. It is important to emphasize that these were not direct responses to requests from buyers—managers regularly de- scribed processes of how they worked to stay ahead of de- mand, and outsiders described firms’ organizational choices that were unprecedented in the local sector. For their part, buyers expressed satisfaction with the upgraded firms from which they sourced, but had little immediate notion of a dis- tinctly “Guatemalan” upgrading model. The distinctiveness of this model was evident in a variety of different areas, including healthcare, safety, and worker train- ing. Regarding health, many Guatemalan companies offered a surprisingly broad array of health services to workers without extra charge. The most advanced example of this was Bluej-

- 22. eans Mundial, which hired dedicated full-time staff in order to offer free eye care, gynecology, and social worker services to all employees, as well as pediatric services to their children. In the realm of workplace safety, companies such as Deporti- vas have taken it upon themselves to custom-design safety equipment such as fume hoods in an attempt to combine com- fort, safety, and mechanical efficiency, leading to what one prominent local labor NGO called a “culture of compliance,” that is, an active desire to meet the spirit of the laws, as op- posed to calculated evasions of sanction (Gunningham, Ka- gan, & Thornton, 2003 Ch. 5). While such design innovations are less common than health clinics and special- ized education resources, they are yet another illustration of the tendency of Guatemalan firms to view increased invest- ments and innovations oriented toward the production floor itself as a crucial aspect of competitiveness. Moreover, many of these firms went extremely far in developing a ‘local culture’ intended to enhance workers’ enthusiasm. Examples of this in- clude firm-supported soccer leagues, daily morning gospel mu- sic sessions, and social spaces designed with worker input. The specialized training and education went significantly above basic on-the-job training. While many of the firms’ training resources were apparel-specific, many also were not. Firms such as ChaquetaModa and Deportivas had made sig- nificant investments in literacy and general education, with Deportivas offering a form of high-school equivalency that is also tied to promotion options that extend into management. Beyond literacy, ChaquetaModa has come to offer classes in human relations, mechanical skills, computer-based plotter technology, first aid/workplace hazards, human resources, environmental training, leadership, nutrition, reproductive health, and recycling. In other cases, many training options have been offered by the national garment exporters’ associa- tion (VESTEX), which is discussed in Section 5c.

- 23. In contrast, in-house design was mostly absent in Guate- mala. Only one firm, Bluejeans Mundial, had its own design department. While the other firms generally did not have the capacity to create original garment designs, many were con- scious of the importance of design and collaborated with buy- ers—for example, to suggest modifications to a design that would make production cheaper without sacrificing quality. This was a service offered by nearly all of the Guatemalan firms, and managers frequently spoke of buyers making use of their firms’ advice on design adjustments. For most Guate- malan upgraders, it was clear that their path forward ran through at least specialized design consulting, if not original garment design itself. (c) Upgrading firms in Colombia In contrast to Guatemalan firms, Colombian firms seem to have developed a niche for themselves where competitive advantage stems primarily from capacity in garment design. Table 2. Characteristics of upgrading Firms in Guatemala and Colombia Companya Country #Workers Age (years) Owner-ship Product(s) Buyer(s)b Health Clinic &/or Extra health benefits Special-ized Ed/Training Physical health/safety improve-ments

- 24. In-house design Chaqueta-Moda GUA 950 9 USA Fashion winter jackets JC Penney, Burlington, Lord & Taylor, DKNY + + � � Polo-Amala GUA 3,000 20 as an exporter GUA Polo shirts, tshirts, infant clothing Direct-order catalogs � � � � Maxi Sports GUA 1,450 8 KOR t-shirts Wal-Mart, Target, K- Mart + � + � Bluejeans Mundial GUA 15,000 20 GUA Denim jeans Calvin Klein, Old Navy/ Gap, Levi’s, The Limited + + + + Hermanos de Fe GUA 420 18 GUA Denim jeans Dickies, Old Navy, Timberland, Target + + � � Deportivas GUA 1,000 10 GUA Perform-ance athletic

- 25. wear Nike, Rawlings, Under Armour � + + � Moda Universal GUA 8,000 10 KOR t-shirts, shorts, swimwear Old Navy, K-Mart, Gap, Wal-Mart + + + � Caballeros COL 500 25 COL Suits, shirts, shorts Perry Ellis, domestic retail chains (e.g., Tennis) � � � + Tecni-Lavados COL 250 18 COL Laundry services, mostly for denim Domestic garment exporters � � � +c DenimPais COL 3,800 14 COL Denim jeans Levi’s, Old Navy, Ralph Lauren, Hilfiger, Calvin Klein

- 26. � � � + Fiesta Jeans COL 1,400 35 COL Denim Jeans Levi’s, Gap � � � � Viajantes COL 290 25 COL Men’s shirts, polos, underwear Mostly Latin American supermarket chains � � � + Moda Clasica COL 1,300 29 COL Suits, denim jeans Polo, Oxford Industries � � � + Intimoda COL 1,030 20 COL Under-wear, lingerie, pajamas, t-shirts Sarah Lee, Vanity Fair � � � + Guatemala Total 5 5 4 1 Colombia Total 0 0 0 6 a All company names are fictionalized to maintain anonymity. b Lists of buyers are not exhaustive and may have changed since time of receiving information from the firm. c For this firm the design process involves the creation of novel washes/treatments for fabrics; these processes are intended to lend unique esthetic characteristics to a garment. L O C A

- 28. 2126 WORLD DEVELOPMENT Although the Colombians were also full-package producers, these firms were a stark contrast to Guatemala’s in labor con- trol, industrial relations, and human resources practices. In Colombia, nearly all firms visited employed time-and-motion studies to manage worker productivity; none visited or inter- viewed displayed or made mention of any of the kinds of above-government minimum training, services, or benefits ob- served in Guatemala. These Colombian Managers could cite only a few specific, plausible outlets to responding to or getting ahead of the com- petition: substituting capital for labor, pushing productivity higher through time studies, and adding high value-added ser- vices such as garment design in order to better attract (and at- tract better) buyers. Absent was anything like the political and discursive framework in Guatemala that growth in apparel exporting was part of a social mission to move forward from civil war into an East Asia-like path of development. Given these differences, it is worth considering how equivalent va- lue-chain outcomes can be achieved in this case. (d) A note on market equifinality One of the crucial components of competitiveness in jeans production, particularly at the high end, is post-assembly washing and finishing. It involves putting the jeans through special operations, whether with chemicals or abrasive objects such as pumice stones, and usually involves a great deal of ex- tra handwork, for example, the application of Dremel tools, sandpaper, sandblasting, and other popular “destruction” methods intended to add an “authentic” quality to the gar- ment. Such practices are common in both countries. Very important to these processes is that they capture the subtlety

- 29. American and other consumers seek when they buy already worn-looking jeans. A minor change in the type of fading or abrasion applied to jeans can act as a different signifier of sub- culture for the wearer, and this very often factors into buying decisions. In Guatemala, managers of one firm became very animated describing the exacting esthetic demands of buyers, who might require that “the whiskers [radial lines of fading created on the front of the jeans] come alive,” or that fading be applied to the front watch pocket of a pair of jeans to con- vince others that the wearer is “a sex machine, he always keeps a condom in his pocket.” (These paraphrases made by the Guatemalan interviewees come from buyers who also com- monly source from Colombian firms.) It is within this difficult space for interpretation that we see room for firms to establish different means of controlling and investing in the production floor, as well as distributing skill throughout the firm to meet the same product expectations. These companies use fundamentally different organizational routines to replicate what are extremely idiosyncratic and dif- ficult-to-capture product attributes. There are at least two fac- tors deciding whether a firm will establish itself in this product niche. First is reputation: has the manufacturing firm estab- lished credibility on the basis of its aggregate output capacity, the sophistication of its previous work, and its demonstrated ability to provide goods at-cost and on-time? This is funda- mentally a question of track record as a supplier delivering or- ders that may be extraordinarily demanding in terms of quality, quantity, and time to delivery. Second, there is the is- sue of samples: whether through original designs or otherwise, this is the physical manifestation of a supplier’s know-how that buyers can tangibly scrutinize before placing an order. As interviews with brand and retail buyers in particular illus- trated, the frontier of competition in these value chain seg- ments—where Latin American producers create space to stand in the competition with Asia—is not only quick turn-

- 30. around, but a set of capacities in fashion and marketing that makes these firms start to look more like consultants in the anticipation of future, possibly fleeting demand than mere producers fulfilling orders. The remaining issue is what factors can drive organizational variation such as that observed in bluejeans producers across the two countries. Data from the field point overwhelmingly to an array of factors in local his- tory, and historical research deepens the plausibility of this explanation. 5. ACCOUNTING FOR THE DIFFERENCES In light of the state of the literature, the field observations described above show that there are important gaps to be ex- plored between the known mechanisms of value chain gover- nance and the differences observed in the organization of Guatemalan versus Colombian firms. Because buyers showed satisfaction with firms from both countries, sometimes for the same goods, it was necessary to look both across the inter- views of various actors for accounts of firm learning, as well as into the histories of these sectors in the context of national development trajectories, to gain more leverage on what could drive variation. The following three factors were induced as the most compelling. (a) Trade relations with the United States Although the GVC literature tends to cast government into a somewhat stereotypical role relegated to ‘background’ rules such as quality, labor, or environmental standards and laws (Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002), a strong exception to this re- gards whether developing-country firms are producing for par- ticular regional market segments, often under a preferential trade agreement. In the research that has focused on this topic, there is a strong consensus that regional trade agreements tightly bind producers and block them out of the highest va- lue-added segments of the value chain (Bair & Dussel Peters,

- 31. 2006; Dussel Peters, 2008; Gibbon, 2003). While this paper does not dispute the fact that preferential trade agreements usually follow a logic far more to the benefit of firms in the developed countries than those in the periphery (e.g., NAFTA and CAFTA’s logic of helping American textile producers to lower costs while tying their suppliers’ hands on the materials they source), the case of Guatemala’s upgraded factories shows clearly how these trade agreements can, perhaps even in spite of their formal stipulations, serve as occasions for working with limitations to produce success and innovation in the value chain. In the case of Guatemala, a now almost 30-year history of preferential trade agreements with the US forced manufactur- ers to focus on competitiveness as a shopfloor-based phenom- enon. That is, in the case of Guatemala and other Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI) beneficiaries, tariff-free status from 1983 to 2000 allowed only the most basic assembly operations (lar- gely sewing) to take place in the exporting country. Even after 2000, with the expansion of the CBI into the Caribbean Basin Trade and Promotion Act (CBTPA), and extension of tariff- free privileges to products where cut, make, trim, and finishing operations were performed in Central America, firms’ main source of differentiation was in how they managed production workers. It was not until the enactment of CAFTA in 2005 that every aspect of the production process, from textiles for- ward, could be performed in a Central American country 6 (Gelb, 2005; King & N., 2004; USTR, 2007; VESTEX, LOCAL MEANS IN VALUE CHAIN ENDS 2127 2005). Colombian firms, lacking this flotation device offered by the US to Guatemala and Central America, sought dry ground at the top of the value chain and attempted to institu-

- 32. tionalize competitiveness through garment design, an activity that was largely decoupled from the production floor. This helps to account for the space of attention, but not the practices that occupied that space. Managers of firms in Gua- temala could have, as a community, applied their collective genius to as-yet unheard-of innovations in a Taylorist direc- tion. Similar to Cammett’s observations of business associa- tion activity in Morocco and Tunisia (Cammett, 2005), the same set of material interests can be pursued by different means, depending on a group’s process of constructing the ide- ational frame that they use to pursue these interests. The fol- lowing factors are suggestive of differences on the “idea” part of the equation. (b) Timing and relationship of industry emergence to national development priorities In Colombia, the story of apparel and manufactures in gen- eral dates much farther back, and shows much more continu- ity than in Guatemala. While Colombia has had extensive experience in the modern manufacture of apparel and tex- tiles—to the point where textile companies, emerging early in the 20th century, formed some of the largest and most mod- ernizing corporations in the country (Montenegro, 2002)— Guatemala hardly shifted its focus on agriculture and primary product exports from colonial times into the late 20th century. And although Colombia was itself a very coffee-dependent country, its longstanding practice of import substitution industrialization (ISI) has no comparable equivalent in Guate- mala. Furthermore, while Colombia is popularly known as a country of violence and upheaval, it was one of the most eco- nomically stable Latin American countries after World War II, and arguably the only major economy in the region to avoid experiencing the 1980s as a ‘lost decade’ for economic growth (Edwards, 2001). As such, Colombia did not have to undergo

- 33. market liberalization with the same urgency as its regional counterparts during this period. Although national policy had taken steps away from an import substitution model as early as the 1960s (Bushnell, 1993, p. 235), Colombia’s charter membership in the Andean Group 7 essentially bound it to a set of highly protective policies that shunned foreign invest- ment and encouraged domestic production over exports (Ber- ry & Thoumi, 1977; Edwards, 2001). In the specific area of apparel manufacturing for export to the US, Morawetz shows that Colombia’s sector dates back at least to the late 1960s, but was largely ignored as an object of policy, overshadowed as it was by coffee and textiles (Morawetz, 1981). In essence, for Colombia in the late 1980s and 1990s, apparel exporting never represented a locus of significant economic or social transformation—if anything, textiles and apparel were repre- sentative of a stale economic growth paradigm. To the extent that there was ever economic diversification in modern Guatemala, it was mostly in “non-traditional” agri- cultural exports such as fruit, winter vegetables, and ornamen- tal plants (UNCTAD, 2010, p. 19). This trend, mixed with the intensification of civil conflict in the late 1970s and early 1980s (and its attendant repulsion of foreign capital), resulted in an effective de-industrialization in the 1980s, though there had not been very much industrial development to dismantle up to that point. In the early-to-mid 1980s, the Guatemalan econ- omy was hollowing out with several years of overall negative GDP growth (BANGUAT, 2006), a 60% decrease in real pub- lic investment (ibid.), overall exports decreasing by about 35%, massive displacement of rural populations into the capital city, and capital flight (Jonas, 1991). The apparel export industry became a device for reversing many of these negative trends. The ostensible goals of an ap- parel export sector—for business and political elites, and even for civil society groups who were nevertheless wary of other

- 34. possible effects—were domestic capital diversification, attrac- tion of foreign investment, and the integration and employ- ment of the new urban poor who had been displaced from the countryside (AVANCSO, 1994). Time and again, intervie- wees from inside and outside of the companies spoke of the purpose of business and competition in terms of a narrative of recovery, growth, and rejuvenation from their Civil War. Managers cited these as reasons why they experimented in cre- ating health clinics, or their choice in extensive education ef- forts as a means of heightening the logistical efficacy of the firm. Observers from the US State Department and local labor law community pointed to a generational divide wherein busi- ness managers who took the reins after the tumult of the late 70s/early 80s adopted different goals from their predecessors— that is, rather than completely follow Guatemala’s tradition of an agrarian economy of such inequality as to practically guar- antee class conflict (Brockett, 1998), they sought a model by which mutual gains for the elites and masses could be found. Observers and factory managers in Colombia, in contrast, had virtually no larger social imperative coloring their stories of how they compete. Finally, Guatemala’s export-oriented model, in combination with its preferential access to the US market, facilitated the preponderance of Korean investment observed there. The Korean influence on Guatemalan maquilas has been rather complex: for example, during field research, inspectors from the Ministry of Labor observed that some of these firms, in the early years of Guatemala’s maquiladora experience, were among the worst offenders on labor issues. Yet these same inspectors, along with members of NGOs and the labor law community, all observed that these firms had been socialized by their business peers and government institutions into a more “Guatemalan” style of management, sometimes eventu- ally becoming model compliers with the labor code. Further- more, many of the high-performance techniques—for

- 35. example, bundling and cell-based floor models, or advanced functions of quality control and fabric dyeing—were absorbed by Guatemalan-owned firms from their Korean peers. This happened through hiring Korean managers, or at times, through contact at the nexus point of the local business asso- ciation (VESTEX). As such, the implications for Korean own- ership extend beyond the logic of Korean HQs reserving the highest value-added functions for themselves and triangulat- ing production between Guatemala and other locales. Rather, both Korean and Guatemalan firms based in Guatemala hybridized each other’s styles and tools to a surprising degree, something that would not have likely happened had Guate- mala introduced its apparel export strategy under a protected model like Colombia’s. (c) Education and socialization of national business elites During field research, interviewees discussed two important streams of training and education that have specifically im- pacted business elites’ approaches to upgrading. First, there is education and work experience abroad. Based on the firms surveyed in this research, it was far more common for managers in Guatemala to have either spent time working in or to have originally come from another country. Of upgrad- ing firms interviewed in Guatemala, nearly all managers of 2128 WORLD DEVELOPMENT nationally-owned firms 8 had studied or worked in the US at some point; three other firms had managers from other coun- tries (South Korea and the Philippines). In Colombia, all of the firm managers were Colombian and described their profes- sional backgrounds as taking place in-country. When asked about their tinkerings and often novel work-

- 36. floor practices/HR policies, managers in Guatemala usually cited their work experiences abroad. We see examples of this in firms such as Deportivas, where the General Manager’s engineering experience abroad prompted him to spend time with workers on the line and apply his observations and work- ers’ feedback to new, in-house inventory and software systems; or one of the owners of Hermanos de Fe, whose time working for a fashion company in Los Angeles influenced their early and heavy investment in jeans washes, rare for a firm of their size; or also the General Manager of ChaquetaModa, a Filip- ina whose prior experience in industrial engineering informed a custom approach to their modular production system, as well as the firm’s prioritization of an almost unheard-of amount of trainings for line operators. Regarding prior education, in Colombia, where the domes- tic higher education resources are much greater, 9 business elites are more likely to move through their careers without stepping outside of a local paradigm of thinking on business competition and industrial relations. In Guatemala, where more business owners seek their educations abroad, there is an exposure to a wider variety of labor market structures, forms of business competition, and paths to increasing pro- ductivity. These broader influences have in turn helped shape the sec- ond stream of influence, that of business associations. Guate- mala and Colombia have two very different industry associations which focus on apparel exports—VESTEX in Guatemala, and INEXMODA in Colombia. Because of its origins as the national apparel export quota office under the MFA, VESTEX by default had ties to all of the exporters in the country. When it became clear in 1995 that the MFA would come to an end, VESTEX decided to transform itself into an organization that would support the industry as it transitioned out of a quota-protected framework. As one of

- 37. the subcommissions of a national non-traditional exporters’ association (AGEXPRONT), it came to quickly outstrip the dimensions of the larger organization, coordinating national conferences and eventually hiring 19 full-time staff members, in contrast to an average of one or two employees on other AGEXPRONT subcommittees. This prominence has also led to political influence, with former VESTEX administrators receiving appointments as Ministers and Vice-Ministers in the Presidential Cabinet, usually in the Ministry of the Economy. One of the main outcomes of VESTEX’s organizational transformation efforts was its full-package training programs, which between the start of 1999 and the end of 2005 trained employees from nearly 40 different firms in a 13-module course covering such topics as risk analysis, costing, marketing, and supply chain management. Its method for curriculum design was based almost entirely on accumulating the knowledge of local lead firms that were already full-package producers (who are also its charter members, and whose managers sit on the VESTEX board), as well as having many of them serve as teachers in its training workshops. VESTEX’s model for full-package training has been replicated to varying degrees of intensity and success in other thematic areas, such as secu- rity, computer plotting, and most recently, garment design. More recently, VESTEX has transferred the implementation of most of its courses to the national training institute (INTE- CAP). Nonetheless, VESTEX’s model, which involves organi- zational staff working on-site in factories, tends to be more hands-on than that of INEXMODA, which largely serves as a broker of demand information between foreign markets and domestic firms. In focusing on international trade fairs and the publication of fashion design manuals, INEXMODA gave extra weight to the tendency in Colombia to focus on fashion as the route to higher value added. 6. LOCAL MEANS IN VALUE CHAIN ENDS: RULES, RESOURCES, AND IDEAS

- 38. The goals of the above exposition were: (1) to establish that Guatemalan and Colombian apparel firms have developed nationally distinct methods of upgrading in a context of mar- ket equifinality or near-equifinality, and (2) to develop propos- als regarding possible extra-chain influences on these outcomes. These proposals refer to differences in local history, and they suggest that the differences in outcome are strongly tied to how rules do or do not fix managers’ attention to cer- tain spaces, as well as what practices they are prepared to en- act in those spaces. In terms of future prospects for the Guatemalan and Colombian apparel industries, a few points beyond the usual caveat of unpredictability (especially given both the history of the apparel industry and current volatility in global de- mand) can be made: first, that Guatemala and Colombia, in achieving similar value chain ends through different organiza- tional means, have each developed a strong core of upgraders who understand that they must anticipate the needs of their buyers through logistically nimble and efficient delivery of hard-to-replicate, complex garments. The upgraders in the sample presented here are among the best-prepared firms to take advantage of any future demand for these capacities. Relative strength notwithstanding, there are important open questions as to the long-term future growth trajectories of these industries, and consequently, what lessons these cases have for firm- and state-level capacity-building. Guatemala’s industry seems to be settling into a smaller core of firms where the low-cost, non-upgraded firms are disappearing. This could call into question the overall visibility of Guatemala as a des- tination for sourcing, apart from the immediate performance of remaining suppliers. Furthermore, while the story of VES- TEX holds intriguing possibilities for training firms, it is cur- rently unclear what VESTEX members and their many friends

- 39. in government are learning from the past 20–30 years of appa- rel manufacturing in Guatemala; many believe that the most important policy issues facing the industry are keeping mini- mum wage flat (Quiñones, 2008), which obviously does not emphasize the kind of workfloor investments observed and interpreted above. If VESTEX’s preoccupation with wages prevails over a focus on sophisticated human resources and training methods, then Guatemala could converge further with Colombia, stratifying the production of value-added within the firm and leaving the situation of floor workers clo- ser to a generic global standard for apparel. However, if cor- rect in its characterization and analysis, this paper suggests another route: namely, further investment in resources and techniques to build quality, skill, efficiency, and product uniqueness into the basic work process through worker train- ing, education and welfare, a la a high-performance work sys- tems approach (Applebaum, Bailey, Berg, & Kallenberg, 2000; Osterman, 1994). Certainly, given the extreme competitiveness of wages globally, it stands to reason that VESTEX and its members could benefit from seeking policy support on areas other than this. LOCAL MEANS IN VALUE CHAIN ENDS 2129 In contemporary research, we see strains in both political science and sociology where the separate impulse of ideas helps to explain outcomes in the political economy (Blyth, 2002; Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006; Hall, 1993; Somers, 1992). In a large cross-national, cross-industry survey of firm-level competitive strategies, Berger also discusses the no- tion of ‘dynamic legacies,’ which represent an accumulation of local experiences, as producing surprising variety in competi- tion under conditions of globalization (Berger, 2006). All of these suggest a highly agency-oriented version of competition, where experiences and ideas serve as markers in actors’ minds,

- 40. allowing them to creatively (and idiosyncratically) interpret what their interests mean, and how they are best served. This extension of the paper’s theoretical ambit into the realm of ideas is rooted in the observation that the mate- rial factors discussed above could have influenced outcomes in many different directions. Granted, an empirical test among Central American countries (who would have had more similar histories in apparel manufacturing, as well as trade relations with the US) would have enabled better precision in terms of isolating the impacts of local political and institutional factors. Nonetheless, the window offered onto upgrading by producers of similar goods in countries with somewhat more divergent industrial histories will hopefully in its own way further the GVC literature’s worthwhile efforts of articulating coherent alternatives to The Washington Consensus’ laissez-faire approach to devel- opment. In particular, the work detailed in this paper sug- gests that future research assess contingency in upgrading as co-produced by buyer demands, legal incentives, and the interpretive backgrounds of local managers. For with- out taking such considerations, much of the developmental possibility of the value chain may remain invisible to the observer. NOTES 1. “Value-added” is usually more referred to in the literature at a conceptual level, rather than operationalized in empirical observation (Gereffi, Humphrey, & Sturgeon 2005; Kogut, 1985; Morrison, Pietrobelli, & Rabellotti, 2008). In this paper, as will be discussed further below, value added will be tracked by unit price, particularly for the close analysis of bluejeans, which involves similarly-sourced materials.

- 41. 2. The notion of value chains as largely either ‘buyer-‘ or ‘producer- driven’ rests largely on a distinction between industries as either ‘labor-‘ or ‘capital-intensive.’ A buyer-driven chain would be labor- intensive, mean- ing that market entry for producers is relatively easy and therefore tips power in favor of buyers (Gereffi, 1999). 3. This is in contrast to a ‘producer-driven’ value chain, where manufacturers, as opposed to branders/marketers/retailers, are the coor- dinators of internationalized production (Gereffi, 1999). 4. Although Guatemalan and Colombian apparel exports to the US decreased absolutely after 2004, the internal trends of value- added and specialization have largely continued. It would distract from the purpose of this paper to try to interpret data where there was extreme volatility in supply (post-2005) or demand (post-2008) patterns. The more specific year-by-year example of Men’s and Boys’ Trousers should help illustrate the distorting effects of the end of the MFA. 5. The minor role of local sourcing is borne out both by interviews and the available data; in terms of the upgrading firms, owners from both countries professed that their more expensive, high-value-added products

- 42. required materials that local producers were not capable of providing. And although there is no way to discern in the available data the uses toward which imported vs. domestically-produced textiles are being applied, about half of all textiles used in Colombian domestic garment manufacturing are imported (ASCOLTEX, 2006). Furthermore, based on managers’ reports, it stands to reason that exporters use a higher proportion of imported materials than those who produce for a domestic market that is generally less exacting in this regard. Similarly, in Guatemala, the most recent estimate from the local apparel and textile manufacturers’ association (VESTEX), stated that less than 5% of all sourcing materials used in apparel exports were from Guatemala (Paz Antolı́n, 2002). 6. CAFTA was ratified in the United States in 2005. In 2006, it passed in El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Guatemala, in that order. In 2007, the Dominican Republic and Costa Rica enacted the agreement. Panama chose instead to pursue a bilateral free trade agreement, which has yet to be completed. While the ‘yarn-forward’ rule is the general principle of CAFTA, there are certain exceptions where materials can originate from outside the CAFTA area, including pocket and

- 43. lining materials, as well as elastics. 7. The Andean Group was a common market project founded in 1969 between Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and later, Venezuela. The Group still exists, though without Chile and Peru as members. 8. The managers of Bluejeans Mundial, Hermanos de fe, and Deportivas. 9. In Colombia, as of 2005, the national population was just under 45 million (World Bank 2008), and there were 276 institutions of higher education, 81 of which were public (Ministerio de Educacion, 2005). Just under 840,000 students attended these schools (SNIES, 2005) In Guate- mala, the most recent data available dates from 1999, when there were 9 institutions of higher education nationwide serving approximately 152,000 students in a nation of just below 11 million (Funes, 2001; World Bank, 2008). REFERENCES Abernathy, F., Volpe, A., & Weil, D. (2006). The future of the apparel and textile industries: Prospects and choices for public and private actors. Environment and Planning A, 38(12), 2207–2232. Amsden, A. (1994). The textile industry in Asian

- 44. industrialization: A leading sector institutionally?. Journal of Asian Economics, 5(4), 573–584. Amsden, A. (2001). The rise of ‘The Rest’: Challenges to the west from late-industrializing ECONOMIES. New York: Oxford University Press. Applebaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., & Kallenberg, A. L. (2000). Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ASCOLTEX (2006). “2006.” [A statistical compendium produced inter- nally but provided to the author by La Asociación Colombiana de Productores Textiles.]. AVANCSO (Asociacion Para el Avance de las Ciencias Sociales) (1994). El Significado de la Maquila en Guatemala. Guatemala City: AVAN- CSO. 2130 WORLD DEVELOPMENT Bair, J. (2005). Global capitalism and commodity chains: Looking back, going forward. Competition & Change, 9(2), 153–180. Bair, J. (2008). Analysing global economic organization:

- 45. Embedded networks and global chains compared. Economy and Society, 37(3), 339–364. Bair, J., & Dussel Peters, E. (2006). Global commodity chains and endogenous growth: Export dynamism and development in Mexico and Honduras. World Development, 34(2), 203–221. Bair, J., & Gereffi, G. (2001). Local clusters in global chains: The causes and consequences of export dynamism in Torreon’s blue jeans industry. World Development, 29(11), 1885–1903. Banco de Guatemala (BANGUAT) (2006). “Sistema de Cuentas Nacio- nales (Año Base 1958)” http://banguat.gob.gt/inc/main.asp?i- d=1783&aud=1&lang=1. Bazan, L., & Navas-Aleman, L. (2004). The underground revolution in the SInos valley: A comparison of upgrading in global and national value chains. In H. Schmitz (Ed.), Local enterprises in the global economy: Issues of governance and upgrading (pp. 110–139). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. Berger, S. (2000). Globalization and politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 43–62. Berger, S. (2006). How we compete: What companies around

- 46. the world are doing to make it in today’s global economy. New York: Random House. Berry, A., & Thoumi, F. (1977). Import substitution and beyond: Colombia. World Development, 5(1/2), 89–109. Blyth, M. (2002). Great Transformations: Economic ideas and institutional change in the twentieth century. New York: Cambridge University Press. Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2006). On justification: Economies of worth. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Brockett, C. D. (1998). Land, power and poverty: Agrarian transformation and political conflict in Central America (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO and Oxford: Westview Press. Bushnell, D. (1993). The making of modern Colombia: A nation in spite of itself. Berkeley: University of California Press. Cammett, M. (2005). Fat cats and self-made men: Globalization and the paradoxes of collective action. Comparative Politics, 37(4), 379–400. DANE (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadı́stica, Colom- bia) (2005). http://www.dane.gov.co.

- 47. Dion, D. (1998). Evidence and inference in comparative case study. Comparative Politics, 30(2), 127–145. Dos Santos, T. (1970). The structure of dependence. The American Economic Review, 60(2), 231–236. Dussel Peters, E. (2008). GCCs and development: A conceptual and empirical review. Competition and Change, 12(1), 11–27. Edwards, S. (2001). The economics and politics of transition to an open market economy: Colombia. Paris: OECD. Foucault, M., Burchell, G., Gordon, C., & Miller, P. (Eds.) (1991). The foucault effect: Studies in governmentality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Evans, P. (1997). The eclipse of the state? reflections on stateness in an era of globalizations. World Politics, 50(1), 62–87. Frundt, H. J. (1998). Trade conditions and labor rights: US initiatives, Dominican and Central American responses. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. Fuentes, H. (1998). Guatemala: Futuro del Sindicalismo, Sindicalismo del Futuro. Guatemala: Magna Terra Editores.

- 48. Fuentes, A. (2007). A Light in The Dark: Labor Reform in Guatemala During the FRG Administration, 2000-2004. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. Funes, M. (2001). “Educación Superior en Guatemala.” Theorethikos, 5(2), http://www.ufg.edu.sv/ufg/theorethikos/contenido.htm . Last accessed July 11, 2008. Gallagher, K., & Zarsky, L. (2007). The enclave economy: Foreign investment and sustainable development in mexico’s silicon valley. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Gelb, B.A. (2005). “CRS Report for Congress: DR-CAFTA, Textiles, and Apparel.” Congressional Research Service, Order Code RS22150, http://www.house.gov/spratt/crs/RS22150.pdf. Gellert, P. L. (2003). Renegotiating a timber commodity chain: Lessons from Indonesia on the political construction of global commodity chains. Sociological Forum, 18(1), 53–84. Gereffi, G. (1999). International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. Journal of International Economics, 48(1), 37–70.

- 49. Gereffi, G., & Korzeniewicz, M. (Eds.) (1994). Commodity chains and global capitalism. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104. Gibbon, P. (2003). The African growth and opportunity act and the global commodity chain for clothing. World Development, 31(11), 1809–1827. Gibbon, P., Bair, J., & Ponte, S. (2008). Governing global value chains: An introduction. Economy and Society, 27(3), 315–338. Gibbon, P., & Ponte, S. (2008). Global value chains: from governance to governmentality?. Economy and Society, 37(3), 365–392. Gibbon, P., & Ponte, S. (2009). Trading down: Africa, value chains, and the global economy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2005). Upgrading in global value chains: Lessons from Latin American clusters. World Develop- ment, 33(4), 549–573. Gunningham, N., Kagan, R. A., & Thornton, D. (2003). Shades of green: Business, regulation, and environment. Stanford, CA: Stanford

- 50. Univer- sity Press. Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296. Held, D. (2005). At the global crossroads: The End of the Washington consensus and the rise of global social democracy?. Globalizations, 2(1), 95–113. Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2002). How does insertion in global value chains Affect upgrading in industrial clusters?. Regional Studies, 36(9), 1017–1027. ITUC (International Trade Union Confederation) (2009). “Annual Survey of Violations of Trade Union Rights.” http://survey09.ituc- csi.org/ survey.php?IDContinent=0&Lang=EN Last accessed February 27, 2011. Jonas, S. (1991). The battle for Guatemala: Rebels, death squads, and US power. Boulder: Westview Press. Kaplinsky, R. (2001). Globalisation and unequalisation: What can be learned from value chain analysis?. In O. Morrissee, & I.

- 51. Filatotchev (Eds.), Globalisation and trade: Implications for exports from margin- alized economies (pp. 117–146). London: Frank Cass. King, Jr., N. (2004). “Stitch in time: As US quotas fall, Latin pants makers seek leg up on Asia.” The Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2004, Page A1. Knauss, J. (1998). Modular mass production: High performance on the low road. Politics and Society, 26(2), 273–296. Kogut, B. (1985). Designing global strategies: Comparative and compet- itive value-added chains. Sloan Management Review, 2(4), 15– 28. Kucszynski, P. P., & Williamson, J. (2003). After the Washington consensus: Restarting reform and growth in Latin America. Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics. Lane, C., & Probert, J. (2009). National capitalisms, global production networks: Fashioning the value chain in the UK, USA and Germany. New York: Oxford University Press. Levenson-Estrada, D. (1994). Trade unionists against terror: Guatemala City, 1954–1985. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

- 52. Lopez, C. (2009). “Sindicalismo y Libre Comercio.” El Tiempo: Bogotá. http://media.eltiempo.com/opinion/columnistas/claudialpez/sind ical- ismo-y-libre-comercio_4804348-1 Last accessed Nov. 11, 2010. Ministerio de Educacion Nacional, Republica de Colombia (2005). “Estadı́sticas del Sector.” http://menweb.mineducacion.gov.co/ info_sector/estadisticas/superior/index.html Last accessed July 11, 2008. Montenegro, S. (2002). El arduo tránsito hacia la modernidad: historia de la industria textı́l colombiana durante la primera mitad del siglo XX. Medellı́n: Grupo Editorial Norma, Clı́o. Morawetz, D. (1981). Why the emperor’s new clothes are not made in Colombia. New York: Oxford University Press. Morrison, A., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2008). Global value chains and technological capabilities: A framework to study learning and innovation in developing countries. Oxford Development Studies, 36(1), 39–58. Mortimore, M. (2003). “Illusory competitiveness: The garment assembly model in the Caribbean Basin.” United Nations University Institute for

- 53. New Technologies Discussion Paper Series #2003-11. Nadvi, K., & Halder, G. (2005). Local clusters in global value chains: Exploring dynamic linkages between Germany and Pakistan. Entre- preneurship and Regional Development, 17(5), 339–363. http://banguat.gob.gt/inc/main.asp?id=1783&aud=1&l ang=1 http://banguat.gob.gt/inc/main.asp?id=1783&aud=1&l ang=1 http://www.dane.gov.co http://www.ufg.edu.sv/ufg/theorethikos/contenido.htm http://www.house.gov/spratt/crs/RS22150.pdf http://survey09.ituc- csi.org/survey.php?IDContinent=0&Lang=EN http://survey09.ituc- csi.org/survey.php?IDContinent=0&Lang=EN http://media.eltiempo.com/opinion/columnistas/claudialpez/sind icalismo-y-libre-comercio_4804348-1 http://media.eltiempo.com/opinion/columnistas/claudialpez/sind icalismo-y-libre-comercio_4804348-1 http://menweb.mineducacion.gov.co/info_sector/estadisticas/sup erior/index.html http://menweb.mineducacion.gov.co/info_sector/estadisticas/sup erior/index.html LOCAL MEANS IN VALUE CHAIN ENDS 2131 Neidik, B., & Gereffi, G. (2006). Explaining Turkey’s emergence and sustained competitiveness as a full-package supplier of apparel. Environment and Planning A, 38(12), 2285–2303. Osterman, P. (1994). How common is workplace transformation

- 54. and who adopts it?. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 47(2), 173– 188. OTEXA (Office of Textiles and Apparel) (2009). “Trade Data.” http:// otexa.ita.doc.gov/msrpoint.htm Last Accessed April 30, 2009. Paz Antolı́n, M.J. (2002). Desvistiendo la maquila: Interrogantes sobre el desarrollo de la maquila en Guatemala – una approximación a los conceptos de valor agregado y paquete completo. Proyecto Regional de la Maquila para Centroamérica y la República Dominicana, Serie: Hacı́a Estrategı́as Sindicales Frente a la Maquila, No. 2. Guatemala. Pickles, J. et al. (2006). Upgrading, changing competitive pressures, and diverse practices in the East and Central European apparel industry. Environment and Planning A, 38(12), 2285–2303. Plankey Videla, N. (2005). Following suit: An examination of structural constraints to industrial upgrading in the third world. Competition & Change, 9(4), 307–327. Ponte, S. (2002). The ‘latte revolution’? regulation, markets and con- sumption in the global coffee chain. World Development, 30(7), 1099–1122.