Managerial accounting ii

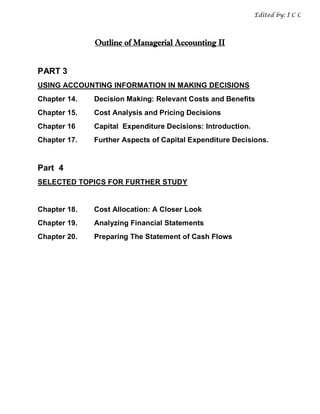

- 1. Edited by: I C C Outline of Managerial Accounting II PART 3 USING ACCOUNTING INFORMATION IN MAKING DECISIONS Chapter 14. Decision Making: Relevant Costs and Benefits Chapter 15. Cost Analysis and Pricing Decisions Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction. Chapter 17. Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions. Part 4 SELECTED TOPICS FOR FURTHER STUDY Chapter 18. Cost Allocation: A Closer Look Chapter 19. Analyzing Financial Statements Chapter 20. Preparing The Statement of Cash Flows

- 2. Chapter 14 Decision Making: Relevant Costs & Benefits Edited by: I C C CHAPTER 14 Decision Making: Relevant Costs and Benefits After completing this chapter, you should be able to: • Describe six steps in the decision-making process and the managerial accountant’s role in that process. • List and explain two criteria that must be satisfied by relevant information. • Identify relevant costs and benefits, giving proper treatment to sunk cost, opportunity costs, and unit costs. • Prepare analyses of various special decisions, properly identifying the relevant costs and benefits. Decision making is a fundamental part of management. Decisions about the acquisition of equipment, mix of products, methods of production, and pricing of products and services confront managers in all types of organizations. This chapter covers the role of managerial accounting information in a variety of common decisions, The Managerial Accountant’s Role in Decision Making The managerial accountant’s role in the decision-making process is to provide relevant information to the managers who make the decisions. Production managers typically make the decisions about alternative production processes and schedules, marketing managers make pricing decisions, and specialists in finance usually are involved in decisions about major acquisitions of equipment. Al of these managers require information pertinent to their decisions. The managerial accountant’s role is to provide information relevant to the decisions faced by managers throughout the organization. Thus, the managerial accountant needs a good understanding of the decisions faced by those managers. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 2

- 3. Chapter 14 Decision Making: Relevant Costs & Benefits Edited by: I C C Managerial Accountant Designs and implements Managers who make accounting information production, marketing, system and finance decisions Make substantive economic decisions affecting operations Steps in the Decision-Making Process Six steps characterize the decision-making process: 1. Clarify the decision problem. Sometimes the decision to be made is clear. For example, if a company receives a special order for its product at a price below the usual price, the decision problem is to accept or reject the order. But the decision is seldom so clear and unambiguous. Perhaps demand for a company’s most popular product is declining. What exactly is causing this problem? Increasing competition? Declining quality control? A new alternative product on the market? Before a decision can be made, the problem needs to be clarified and defined in more specific terms. Considerable managerial skill is required to define a decision problem in terms that can be addressed effectively. 2. Specify the criterion. Once a decision problem has been clarified, the manager should specify the criterion upon which a decision will be made. Is the objective to maximize profit, increase market share, minimize cost, or improve public service? Sometimes the objectives are in conflict, as in a decision problem where production cost is to be minimized but product quality must be maintained. In such cases, one objective is specified as the decision criterion- for example cost minimization. The other objective is established as a constraint- for example, product quality must not fall below standard. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 3

- 4. Chapter 14 Decision Making: Relevant Costs & Benefits Edited by: I C C 3. Identify the alternatives. If a machine breaks down, what are the alternative courses of action? The machine can be repaired or replaced, or a replacement can be leased. But perhaps repair will turn out to be more costly than replacement. Determining the possible alternative is a critical step in the decision process. 4. Develop a decision model. A decision model is a simplified representation of the choice problem. Unnecessary details are stripped away, and the most important elements of the problem are highlighted. Thus, the decision model brings together the elements listed above the criterion, the constraints, and the alternatives. 5. Collect the data. Although the managerial accountant often is involved in step 1 through 4, he is chiefly responsible for step 5. Selecting data pertinent to decisions is one of the managerial accountant’s most important roles in an organization. 6. Select an alternative. Once the decision model is formulated and the pertinent data are collected, the appropriate manager makes a decision. Obtaining Information: Relevance. Accuracy. And Timeline What criterion should the managerial accountant use in designing the accounting information system that supplies data for decision making? Three characteristics of information determine its usefulness. Relevance Information is relevant if it is pertinent to a decision problem. Different decisions typically will require different data. The primary theme of this chapter is how to decide what information is relevant to various common decision problems. Accuracy Information that is pertinent to a decision problem must also be accurate, or it will be 0f little use. This means the information must be precise. Conversely, highly accurate but irrelevant data are of no valve to a decision maker. Timeliness Relevant and accurate data are of valve only if they are timely, that is, available in time for a decision. Thus, timeliness is the third important criterion for determining the usefulness of information To summarize, the managerial accountant’s primary role in the decision- making process is twofold: 1. Decide what information is relevant to each decision problem. 2. Provide accurate and timely data, keeping in mind the proper balance between these often conflicting criteria. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 4

- 5. Chapter 14 Decision Making: Relevant Costs & Benefits Edited by: I C C Relevant Information What makes information relevant to a decision problem? Four considerations are important. Bearing .on the future: The consequences of decisions are borne in the future, not in the past. To be relevant to a decision, cost or benefit information must involve a future event. Different under Competing Alternative: Relevant information must involve costs or benefits that differ among the alternative. Costs or benefits that are the same across all the available alternatives have no bearing on a decision. Need for Predictions: Since relevant information involves future events, the managerial accountant must predict the amounts of the relevant costs and benefits. In making these predictions, the accountant often will use estimates of cost behavior based on historical data. There is an important and subtle issue here. Relevant information must involve costs and benefits to be realized in the future. However, the accountant’s predictions of these of these costs benefits often are based on data from the past. Unique versus Repetitive Decision: Unique decisions arise infrequently, or rely once. Compiling data for unique decisions usually requires a special analysis by the managerial accountant. The relevant information often will be found in many diverse places in the organization’s overall information system. In contrast, repetitive decisions are made over and over again, at either regular or irregular intervals. Importance of identifying Relevant Costs and Benefits Why is it important for the managerial accountant to isolate the relevant costs and benefit in a decision analysis? The reasons are twofold. First, generating information is a costly process. The relevant data must be sought, and this requires time and effort. By focusing on only the relevant information, the managerial accountant can simplify and shorten the data gathering process. Second, people can effectively use only a limited amount of information. Beyond this they experience information overload, and their decision-making effectiveness declines. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 5

- 6. Chapter 14 Decision Making: Relevant Costs & Benefits Edited by: I C C IDENTIFYING RELEVANT COSTS AND BENEFITS To illustrate how managerial accountants determine relevant costs and benefits, we will consider several decisions faced by management of Worldwide Airways. The airlines flies routes between the United States and Europe, between various cities in Europe, and between the United States and several Asian cities. Sunk Costs Sunk costs are costs that already have been incurred. They do not affect any future cost and cannot be changed by any current or future action. Sunk costs are irrelevant in decisions, as the following two examples show. Book value of Equipment: At Paris Airport, Worldwide Airways has three- year-old loader truck used to load in-flight meals onto airplanes. The box on the truck can be lifted hydraulically to the level of a jumbo jet’s side doors. The book value of this loader, defines as the asset’s acquisition cost less the accumulated depreciation to date, is computed as follows: Acquisition cost of older loader…………………..………….… $100,000 Less: Accumulated depreciation……………………..……...……$ 75,000 Book Value………………………………………………………$ 25,000 The loader has one year of useful life remaining, after which its salvage value will be zero. However, it could be sold now for $5,000. In addition to the annual depreciation of $5,000, Worldwide Airways annually incurs $80,000 in variable costs to operate the loader. These include the costs of operator labor, gasoline, and maintenances. A The Airway’s ramp manager at Paris Airport faces a decision about replacement of the loader. A new kind of loader uses a conveyor belt to move meals into an airplane. The new loader is much cheaper than the old hydraulic loader and costs less to operate. However, the new loader would be operable for only year before it would need to be replaced. Pertinent data about the new loader are as follows: Acquisition cost of new loader………………………..… $15,000 Useful life…………………………………………….…… 1 year Salvage value after one year……………………………….. 0 Annual depreciation………………………………..……… $15,000 Annual operating costs……………………………...………$45,000 Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 6

- 7. Chapter 14 Decision Making: Relevant Costs & Benefits Edited by: I C C The manager’s initial inclination is to continue using the old loader for another year. He exclaims, “We can’t dump that equipment now. We paid $100,000 for it, and we’ve only used it three years. If we get rid of that loader now, we’ll lose $20,000, less its current salvage value of $5,000, amounts to a loss of $20.000. Fortunately, the manager’s comment is overheard by the managerial accountant in the company’s Airport. He points out to the ramp manager that the book value of the old loader is a sunk cost. It cannot affect any future cost the company might incur. To convince the ramp manager that the accountant is right, he prepares the analysis shown below: EXHIBIT 14-2 Equipment Replacement Decision: Worldwide Airways Cost of Two Alternatives (a) (b) (c) Do not Replace Replace Old Old Differential Loaders Loaders Costs (1) Depreciation of old loader …………………………. $25,000 Sunk OR -0- Cost (2) Write-off of old loader’s book value …………… $25,000 (3) Proceeds from disposal of old loader …………. -0- (5,000) $5,000 Relevant (4) Depreciation (cost) of new loader ………………. -0- 15,000 (15,000) data (5) Operating costs ………………………………………….. 80,000 45,000 35,000 Total ………………………………………………………….. $105,000 $80,000 $25,000 Regardless, of which alternative is selected, the $25,000 book value of the old loader will be an expense or loss in the next year. If the old loader is kept in service, the $25,000 will be recognized as depreciation expense; otherwise, the $25,000 cost will be incurred by the company as a write-off of the asset’s book value. Thus, the current book value of the old loader is a sunk cost and irrelevant to the replacement decision. Notice that the relevant data in the equipment replacement decision are items (3), (4), and (5). Each of these items meets the two tests of relevant information: 1. The costs or benefits relate to the future 2. The costs or benefits differ between the alternatives The proceeds from selling the old loader, item (1), will be received in the future only under the “replace” alternative. Similarly, the acquisition cost (depreciation) of the new loader, item (4) is a future cost incurred only under Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 7

- 8. Chapter 14 Decision Making: Relevant Costs & Benefits Edited by: I C C the “replace” alternative. The operating cost, item (5), is also a future cost that differs between the two alternatives. Differential Costs: is shown in the above table by the column entitled Differential Cost. This column shows the difference for each item between the costs incurred under the two alternatives. The computation of differential costs is a convenient way of summarizing the relative advantage of one alternative over the other. Irrelevant Future Costs and Benefits At the headquarter, the manager of flight schedule, is in the midst of making a decision about Atlanta to Honolulu route. The flight is currently nonstop, but, he is considering a stop in San Francisco. He feels that the route would attract additional passengers if the stop is made, there would also be additional variable costs. His analysis is shown in the next table. EXHIBIT 14-4 Flight Route Decision: Worldwide Airways Revenue and Costs under Two Alternatives (a) (b) (c) Relevant or With Stop Irrelevant Nonstop in San Differential Route* Franciscso* Amount+ Relevant (1) Passenger revenue …………………………… $240,000 $258,000 $(18,000) Irrelevant (2) Cargo revenue ……………………………………. 80,000 80,000 -0- Relevant (3) Landing Fee in San Francisco ………………. -0- (5,000) 5,000 Relevant (4) Use of airport gate facilities ………………… -0- (3,000) 3,000 Relevant (5) Flight crew cost …………………………………… (2,000) (2,500) 5,00 Relevant (6) Fuel ……………………………………………………… (21,000) (24,000) 3,000 Relevant (7) Meals and services …………………………….. (4,000) (4,600) 600 Irrelevant (8) Aircraft maintenance …………………………. (1,000) (1,000) -0- Total revenue less costs ……………………. $292,000 $297,900 $5,900 *In columns (a) and (b) parentheses denote costs and numbers without parentheses are revenues. + In Column (c) parentheses denote differential items favoring option (b). The analysis indicates that the preferable alternative is the route that includes a stop in San Francisco. Notice that the cargo revenue (item 2) and the aircraft- maintenance cost (item 8) are irrelevant to the flight-route decision. Although these data do affect future cash flows, they do not differ between the two alternatives. All of the other data differ between the two alternatives. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 8

- 9. Chapter 14 Decision Making: Relevant Costs & Benefits Edited by: I C C Opportunity Costs Another decision confronting the manager of flight schedule is whether to add two daily round-trip flights between Atlanta and Montreal. His initial analysis of the relevant costs and benefits indicates that additional revenue from the flights will exceed their costs by $30,000 per month. Hence, he is ready to add the flights to the schedule. However, the Airways hanger manager in Atlanta, points out that the flight manager has overlooked an important consideration. The Airways currently has excess space in its hanger. A commuter airline has offered to rent the hangar space for $40,000 per month. However, if the Atlanta-to-Montreal flights are added to the schedule, the additional aircraft needed in Atlanta will require the excess hangar space. If worldwide Airways adds the Atlanta- to-Montreal flights, it will forgo the opportunity to rent the excess hangar space for $40,000 per month. Thus, the $40,000 in rent forgone is an opportunity cost of the alternative to add the new flights. An opportunity cost is the potential benefit given up when the choice of one action precludes a different action. The importance of opportunity costs, they are just as relevant as out-of-pocket costs in evaluating decision alternatives. In the Worldwide Airways case, the best action is to rent the excess warehouse space to the commuter airline, rather than adding the new flights. The analysis that supports this conclusion is shown below: EXHIBIT 14-5 Decision to Add Flights: Worldwide Airways (a) (b) (c) Do Not Add Add Differential Flights Flights Amount Additional revenue from new flights Less additional costs ………………………………………………… $30,000 -0- $30,000 Rental of excess hanger space …………………………………………………………….. -0- $40,000 (40,000) Total …………………………………………………………………………… $30,000 $40,000 $(10,000) It is a common mistake for people to overlook or underweight opportunity costs. The $40,000 hangar rental, which will be forgone if the new flights are added, is an opportunity cost of the option to add the flights. It is a relevant cost of the decision, and it is just as important as any out-of-pocket expenditure. Summary Relevant costs and benefits satisfy the following two criteria: 1. They affect the future 2. They differ between alternatives. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 9

- 10. Chapter 15 Cost Analysis & Pricing Decision Edited by: I C C CHAPTER 15 COST ANALYSIS AND PRICING DECISIONS AFTER COMPLETING THIS CHAPTER, YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO: • List and describe the four major influences on pricing decision. • Explain and use the economic, profiting-maximizing price model. • Set prices using cost-plus pricing formula. • Determine prices using the time and material pricing approach. • Set prices in special-order or competitive situations by analyzing the relevant. Setting the price for an organization’s product or services is one of the most important decisions a manager faces. It is also one of the most difficult, due to the number and variety of factors that must be considered. The pricing decisions arises in virtually all types of organizations. Manufacturers set prices for their goods they manufacture; merchandising companies set prices for their goods; service firms set prices for such services as insurances policies, train tickets, park admissions, and bank loans. Non-profit organizations often set prices. For example, government units price vehicle registration, park-use fees and utility services. Public utilities and TV cable companies face political considerations in pricing their products and services, since their prices often must be approved by a governmental commission. In this chapter, we will study pricing decisions, with the emphasis on the role of managerial accounting information. The setting for our discussion is Sydney Sailing Supplies (SSS), a manufacturer of sailing supplies and equipment located in Sydney, Australia. MAJOR INFLUECES ON PRICING DECISIONS Four major influences govern the prices set by Sydney Sailing Supplies: 1. Customer demand 2. Actions of competitors 3. Costs 4. Political, legal, and image related issues. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 10

- 11. Chapter 15 Cost Analysis & Pricing Decision Edited by: I C C Customer Demand The demands of customers are paramount importance in all phases of business operations, from the design of a product to the setting of its price. Product-design issues and pricing considerations are interrelated, so they must be examined simultaneously. For example, if customers want a high-quality sailboat, this will entail greater production time and more expensive raw material. The result almost certainly will be a higher price. On the other hand, management must be careful not to price its products out of the market. Discerning customer demand is a critically important and continuous process. Companies routinely obtain information from market research, such as customer surveys and test-marketing campaign, and through feedback from sales personnel. To be successful, SSS must provide the products its customers want at a price they perceive to be appropriate. Actions of competitors Although Sydney Sailing Supplies’ managers would like the company to have the sailing market to itself they are not so fortunate. Domestic and foreign competitors are striving to sell their products to the same customers. Thus, as SSS management designs products and sets prices, it must keep a watchful eye on the firm’ competitors. If a competitor reduces its price on sales of a particular type, SSS may have to follow suit to avoid losing its market share. Yet the company cannot follow its competitors blindly either. Predicting competitive reactions to its product-design pricing strategy is a difficult but important task for Sydney Sailing Supplies management. Costs The role of costs in price setting varies widely among industries. In some industries, prices are determined almost entirely by market forces. An example is the agricultural industries, where grain and meat prices are market-driven. Farmers must meet the market price. To make a profit, they must produce at a cost below the market price. This is not always possible, so some periods of loss inevitable result. In other industries, managers set prices at least partially on the basis of production costs. For example, cost-based pricing is used in the automobile, household appliance, and gasoline industries. Pricing are set by adding a markup to production costs. Managers have some latitude in determining the markup, so market forces influence prices as well. In public utilities, such as electricity and natural gas companies, prices generally are set by a regulatory agency of the state government. Production costs are of prime importance in justifying utilities rates. Typically, a public utility will make a request to the public. Utility Commission for a rate increase on the basis of its current and projected production costs. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 11

- 12. Chapter 15 Cost Analysis & Pricing Decision Edited by: I C C Balance of market Forces and Cost-Based Pricing: In most industries, both market forces and cost considerations heavily influence prices. No organization or industry can price its products below their production costs indefinitely. And no company’s management can set prices blindly at cost plus a markup with-out keeping an eye on the market. In most cases, pricing can be viewed in either of the following ways, How Are Prices Set? Prices are determined Prices are based on costs, subject to by the market, subject Market to the constraint that Costs the constraint that forces the reaction of costs must be covered in the long run. customers and competitors must be heeded. Political, Legal, and Image-Related Issues Beyond the important effects on prices of market forces and costs are a range of environmental consideration. In the legal area, managers must adhere to certain laws. The law generally prohibits companies from discriminating among their customers in setting prices. Also prohibited is collusion in price setting, where the major firms in an industry all agree to set their prices at high levels. Political considerations also can be relevant. For example, if the firms in an industry are perceived by public as reaping unfairly large profits, there may be political pressure on legislators to tax those profits differentially or intervene in some way to regulate the prices. ECONOMIC PROFIT-MAXIMIZING PRICING Companies are sometimes price takers, which mean their products’ prices are determined totally by the market. Some agricultural commodities and precious metals are examples of such products. In most cases, however, firms have Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 12

- 13. Chapter 15 Cost Analysis & Pricing Decision Edited by: I C C some flexibility in setting prices. Generally speaking, as the price of a product or service is increased, the quantity demanded declines and vice versa. Total Revenue, Demand, and marginal Revenue Curves The trade-off between a higher price and a higher sales quantity can be shown in the shape of the firm’s total revenue curve, which graphs the functional relationship between total sales revenue and quantity sold. SSS total revenue curve for its two-person sailboat, the Wave Dater, is displayed as Fig (A) shown below. The total revenue curve increases throughout its range, but the rate of increase declines as monthly sales quantity increase. To see this, notice that the increase in total revenue when the sales quantity increases from zero to a units is greater than the increase in total revenue when the sales quantity increases from a units to b units. Closely related to the total revenue curve are two other curve, which are graphed in panel (B). The demand curve shows the relationship between the sales price and the quantity of units demanded. The demand curve decreases throughout its range, because any decrease in the sale price brings about an increase in the monthly sales quantity. The demand curve is also called the average revenue curve, since it shows the average price at which any particular quantity can be sold. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 13

- 14. Chapter 15 Cost Analysis & Pricing Decision Edited by: I C C Total Revenue, Demand, and Marginal Revenue Curve EXHIBIT 15-1 Total Revenue, Demand, and Marginal Revenue Curves Dollars Total revenue Curve is increasing throughout its range, but at a declining rate Quantity sold 0 a b per month (A) Total revenue curve Dollars per unit Demand (or average revenue) Marginal revenue Quantity sold per month (B) Demand (or average revenue) curve and marginal revenue curve Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 14

- 15. Chapter 15 Cost Analysis & Pricing Decision Edited by: I C C EXHIBIT 15-1 (CONTINUED) Total Revenue, Demand, and Marginal Revenue Curve Quantity Sold Per Unit Total Revenue Changes in Month Sales Price per Month Total Revenue 10 ………… $1,000 …………… $10,000 ………… $9,500 20 …………. 975 …………… 19,500 ………… 9,000 30 …………. 950 …………… 28,500 ………… 8,500 40 …………. 925 ………….. 37,000 ………… 8,000 50 …………. 900 …………… 45,000 ………… 7,500 60 …………. 875 …………… 52,500 Related to Related to Related to demand total revenue marginal revenue curve curve curve (C) Totaled price, quantity, and revenue data The marginal revenue curve shows the change in total revenue that accompanies a change in the quantity sold. The marginal revenue curve is decreasing throughout its range to show that total revenue increases at a declining rate as monthly sales quantity increases. A tabular presentation of the price, quality, revenue data for SSS is displayed in panel (C). Study this table carefully to see how the data relate to the graphs shown in panel A and B of the exhibit. No matter what approach a manager take to the pricing decision, a good understanding of the relationship will lead to better decisions. Before we can fully use the revenue data, however, we must examine the cost side of SSS business Total Cost and Marginal Cost Curve Understanding cost behavior is important in many business decisions, and pricing is no exception. How does total cost behave as the number of boats produced and sold by SSS changes? Panel (A) of displays the firm’s total cost curve, which graphs the relationship between total cost and the quantity produced and sold each month. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 15

- 16. Chapter 15 Cost Analysis & Pricing Decision Edited by: I C C Total cost increases throughout its range. The rate of increase in total cost declines as quantity increases from zero to c units. To verify this, notice that the increase in total costs when quantity increases from zero to a units is greater than the increase in total costs when quantity increases from a units to b units. The rate of increase in total costs increases as quantity increases from c units upward. To verify this, notice that the increase in total costs as quantity increases from c units to d units is less than the increase in total costs as quantity increases from d units to c units. Closely, related to the total cost curve is the marginal cost curve, which is graphed in panel (B). the marginal cost curve shows the change in total cost that accompanies a change in quantity produced and sold. Marginal cost declines as quantity increases from zero to c units; then it increases as quantity increases beyond c units. Price Elasticity The impact of price changes on sales volume is called price elasticity. Demand is elastic if a price increase has a large negative impact on sales volume, and vice versa. Demand is inelastic if price changes have little or no impact on sales quantity. Cross-elasticity refers to the extent to which a change in a product’s price affects the demand for other substitute products. For example, if SSS raises the price of its two-person sailboat, there may be an increase in demand for substitute recreational craft, such as small powerboats, canoes, or windsurfers. Measuring price elasticity and cross-elasticity is an important objective of market research. Having a good understanding of these economic concepts helps managers to determine the profit-maximizing price. ROLE OF ACCOUNTING PRODUCT COSTS IN PRICING Most managers base prices on accounting product costs, at least to some extent. There are several reasons for this. First, most companies sell many products or services. There simply is not time enough to do a thorough demand and managerial-cost analysis for every product or service. Managers must rely on a quick and straight forward method for setting prices, and cost-based pricing formulas provide it. Second, even though market considerations ultimately may determine the final product price, a cost-based pricing formula gives the manager a place to start. Finally, and most importantly, the cost of a product or service provides a floor below which the price cannot be set in the long run Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 16

- 17. Chapter 15 Cost Analysis & Pricing Decision Edited by: I C C Cost-Plus Pricing Price = cost + (markup percentage × cost) Cost-based pricing formulas typically have the follow general form. Such a pricing approach often is called cost-plus pricing, because the price is equal to cost plus a markup. Depending on how cost is defined, the markup percentage may differ. Several different definitions of cost, each combined with a different markup percentage, can result in the same price for a product or a service. The following table illustrates how SSS management could use several different cost-plus pricing formulas and arrive at a price of $925 for the Wave Darter. Cost-plus formula (1) is based on variable manufacturing cost. Formula (2) is based on absorption (or full) manufacturing cost, which includes an allocated portion of fixed cost manufacturing costs. Formula (3) is based on all costs; both variable and fixed costs of the manufacturing, selling, and administrative functions. Formula (4) is based on all variable costs, including variable manufacturing, selling, and administrative costs. Notice that all four pricing formulas are based on a linear representation of the cost function, in which all costs are categorized as fixed or variable. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 17

- 18. Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction Edited by: I C C CHAPTER 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: An Introduction AFTER COMPLETING THIS CHAPTER, YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO: • Explain the importance of the time value of money in capital-budgeting decisions. • Compute the future value and present value of cash flows occurring over several time periods. • Use the net-present value method and internal-rate-of-return method to evaluate an investment proposal. • Compare the net-present value and internal-rate-of-return method, and state the assumptions underlying each method. Managers in all organizations periodically face major decisions that involve cash flows over several years. Decisions involving the acquisition of machinery, vehicles, buildings, or land are examples of such decisions. Decisions involving cash inflows and outflows beyond the current year are called capital-budgeting decision. Managers encounter two types of capital-budgeting decisions. Acceptance-or-Rejection Decisions: These decisions occur when managers must decide whether or not they should undertake a particular capital investment project. In such a decision, the required funds are available or readily obtainable, and management must decide whether the project is worthwhile. For example, the controller for the city Mountainview is faced with a decision as to whether to replace one of the city’s oldest street-cleaning machines. The funds are available in the city’s capital budget. The question is whether the cost savings with the new machine will justify the expenditure. The analysis of acceptance-or-rejection decisions is the focus of this chapter. Capital-Rationing Decisions: in these decisions, managers must decide which of several worthwhile projects makes the best use of limited investment funds. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 18

- 19. Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction Edited by: I C C CONCEPT OF PRESENT VALVE Before we can study the capital-budgeting methods used to make decisions such as those faced in the city of Mountainview, we first must examine the basic tools used in those methods. The fundamental concept in a capital- budgeting decision analysis is the time value of money. Would you rather receive a $100 gift check from a relative today, or would you rather a receive letter promising the $100 in a year? Most of us would rather have the cash now. There are two possible reasons for this attitude. First, if we receive the money today, we can spend it on that new sweater now instead of waiting a year. Second, as an alternative strategy, we can invest the $100 received today at 10 percent interest. Then, at the end of one year, we will have $110. Thus, there is a time value associated with money. A $100 cash flow today is not the same as a $100 cash flow in one year, two years, or ten years. Component Interest: Suppose you invest $100 today (time o) at 10 percent interest for one year. How much will you have after one year? The answer is $110, as the following analysis shows. $100 $100+ (.10)($100) =$110 Time Time 0 1 year Time 1 The $110 at time 1(end of one year) is composed of two parts, as shown below: Principal. Time 0 amount…………………………………….. $100 Interest earned during year 1 (.10 X $100) ……………………. 10 Amount at time 1……………………………………………… $ 110 Thus, the $110 at time 1 consist of the $100 at time 0, called principal, plus the $10 of interest earned during the year. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 19

- 20. Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction Edited by: I C C Now suppose you leave your $110 invested during the second year. How much will you have at the end of two years? As the following analysis shows, the answer is $121 $100 $100 + (.10)($100) = $110 $110 + (.10)($110) = $121 Time Time 0 Year 1 Time 1 Year 2 Time 2 We can break down the $121 at time 2 into two parts as follows: Amount at time 1…………………………………………….….. $110 Interest earned during year 2 (.10 X $110) …………………. 11 Amount at time 2……………………………………….……… $ 121 Notice that you earned more interest in year 2 ($11) than you earned in year 1 ($10). Why? During year 2, you earned 10% interest on the original principal of $100 and you earned 10% interest on the year 1 interest of $10. When interest is earned on prior periods’ interest, we call the phenomenon compound interest. How about if your invested fund grow over five years period? Give an example….. As the number of years in an investment increases, it becomes more difficult to compute the future valve of the investment using the method shown above. Fortunately, the simplest formula shown below may be used to compute the future value of any investment. F = P (1+r) (1) Where P denotes principal r. denotes interest rate per year n. denotes number of years Using formula (1) to compute the future value after five years of your $100 investment, we have the following computation. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 20

- 21. Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction Edited by: I C C F = P(1+r) = $100(1 + .10) = $100(1.6105) = $161.05 The value of (1 + r) is called the accumulation factor. The values of (1 + r), for various combinations of r and n, are tabulated in separate tables at the of chapter.. Use formula (1) and the tabulated values in Table 1 to compute the future value after 10 years of an $800 investment that earns interest at the rate of 12% per year. Present value: In the discussion above, we computed the future value of an investment when the original principal is known. Now consider a slightly different problem. Suppose you know how much money you want to accumulate at the end of a five-year investment. Your problem is to determine how much your initial investment needs to be in order to accumulate the desired amount in five years. To solve this problem, we start with formula (1). F = P (1+ r) Now divide each side of the preceding equation by (1 + r) P=F 1…. (2) (1 + r) In formula (2), P denotes what is commonly referred to as the present value of the cash flow F , which occurs after n years when the interest rate is r, Let’s try out formula (2) on your investment problem, which we analyzed in the example earlier. Suppose you did not know the value of the initial investment required if you want to accumulate $16.05 at the end of five years in an investment that earns 10% per year. We can determine the present value of the investment as follows: 1 P=F ---------- (1+r) 1 = $161.05 ----------- ( 1 + .10) = $161.05 (..6209) = $100 Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 21

- 22. Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction Edited by: I C C Thus, as we knew already, you must invest $100 now in order to accumulate $161.05 after five years in an investment earning 10 percent per year. The present value of $100 and the future value of 161.05 at time 5 are economically equivalent, giver that the annual interest rate is 10 percent. If you are planning to invest the $100 received now, then you should be indifferent between receiving the present value of $100 now receiving the future value of $161.05 at the end five years. When we used formula (2) to compute the present valve of the $161,05 cash flow at time 5, we used a process called discounting. The interest rate used when we discount a future cash flow to compute its present value is called the discount rate. The value of 1/(1 + r), which appears in formula (2), is called discount factor. Discount factors, factor, for various combinations of r and n, are tabulated in table 3. Suppose you want to accumulate $18,000 to buy a new car in four years, and you can earn interest at rate of 8 percent per year on an investment you make now. How much do you need to invest now? Use formula (2) and the discount factor in Table 3 to compute the present value of the required $18,000 amount needed at the end of four years. Present Value of a Cash-flow Series: the present value problem we just solved involved only a single future cash flow. Now consider a slightly different problem. Suppose you just won $5,000 in the state lottery. You want to spend some of the cash now, but have decided to have save enough to rent a beach during spring break of each of the next three years. You would like to deposit enough in a bank account now so that you can withdraw $1000 from account at the end of each of the next three years. The Money in the bank account will earn 8 percent per year. The question, then, is how much do you need to deposit? Another way of asking the same question is, what is the of a series of three $1000 cash flows at the end of each of the next three years, given that the discount the discount rate is 8 percent.? Present Value? $1,000 $1,000 $1,000 ._____________._____________._____________.______________ Time 0 1 2 3 One way to figure out the answer to the question is to compute the present value of each of the three $1,000 cash flows and add the three present value amounts. We can use formula (2) for these calculations as shown in the panal Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 22

- 23. Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction Edited by: I C C A ………. Notice that the present value of each of the $1,000 cash flows is different, because the timing of the cash flows is different. The earlier the cash flow will occur, the higher is its present value. In looking the example, we obtained the $2,577 total present value by adding three present value amounts. Each of these amounts is the result of multiplying $1,000 by a discount factor. Notice that we can obtain the same final results by adding the three discount factors first, and then multiplying by $1,000. This approach is taken in the example panel B…… The sum of the three discount factors is called an annuity discount factors, because a series of equivalent cash flows is called an annuity. Annuity discount factors for various combinations of r and n are tabulated in Table 4. Now let’s verify that $2,577 is the right amount to finance your three spring-break vacations. Example C shows how your bank account will change over the three-year period as you earn interest and then withdraw $1,000 each year. Future Value of Cash-Flow Series: To complete our discussion of present value and future value concepts, let’s consider the series of $1000 rental payments. Suppose the owner invested each $1000 rental payment in a bank account that pays 8 percent interest per year. How much will the owner accumulate at the end the three-year period? An equivalent question is, what is the future value of the three-year series of $1000 cash flows, given an annual interest rate of 8 percent? Example 5a answers the question in two ways. First, three separate future-value calculations are made using formula (1). Notice that the $1000 cash flow at time 1 is multiplied by (1.08)3, since it has two years to earn interest. The $1000 cash flow at time 2 has only one year to earn interest, and the time 3 cash flow has no time to earn interest. Second, the three-year annuity accumulation factor is used. This factor is the sum of the three accumulation factors used in the first part. The annuity accumulation factors for various combinations of r and n are tabulated in Table 2. Using the Table correctly: when using the tables in the appendix to solve future-value and present-value problems, be sure to select the correct table. Table 1 is used to find the future value of a single cash flow, and Table 3 is used to find the present value of a single cash flow. Table 2 is used in finding the future value of a series of identical cash flow. Be careful not to confuse future value with present value or to confuse a single cash flow with a series of identical cash flows. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 23

- 24. Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction Edited by: I C C DISCOUNTED-CASH-FLOW ANALYSIS With our review of future-value and present-value tools behind us, we can return to the main issue of how to evaluate capital-investment projects. Our discussion will be illustrated by several discussions made by the Mountainreview city government. The controller of Mountainreview routinely advises the mayor and city council on major capital-investment decisions. Currently under consideration is the purchase of a new street cleaner. The controller has estimated that the city’s old street-cleaning machine would last another five years. A new street cleaner, which also would last for five years, can be purchased for $50,470. It would cost the city $14,000 less each year to operate the new equipment than it costs to operate the old machine. The expected cost savings with the new machine are due to lower expected maintenance costs. Thus, the new street cleaner will cost $50,470 and save $70,000 over its five-year life ($70,000 = $14,000 savings per year). Since the $70,000 in cost savings exceeds the $50,470 acquisition cost, one might be tempted to conclude that the new machine should be purchased. However, this analysis is flawed, since it does not account for the time value of money. The $50,470 acquisition cost will occur now, but the cost savings are spread over a five-year period. It is a mistake to add cash flows occurring at different points in time. The proper approach is to use discounted-cash-flow analysis, which takes account of the timing of the cash flows. There are two widely used methods of discounted-cash-flow analysis: the net-present-value method and the internal-rate-of-return method. Net-Present-Value Methods The following four steps comprise a net-present-value analysis of an investment proposal. 1. Prepare a table showing the cash flows during each year of the proposed investment. 2. Compute the present value of each cash flow, using a discount rate that reflects the cost of acquiring investment capital. This discount rate is often called the hurdle rate or minimum desired rate of return. 3. Compute the net present value, which is the sum of the present values of the cash flows. 4. If the net present value (NPV) is positive, accept the investment proposal. Otherwise, reject it. Example 6 displays these four steps for the Mountainview controller’s street- cleaner decisions. In step (2) the controller used a discount rate of 10%. Notice that the cost savings are $14,000 in each of the years 1 through 5. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 24

- 25. Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction Edited by: I C C Thus, the cash flows in those years comprise a five-year, $14,000 annuity. The controller used the annuity discount factor to compute the present value of the five years of cost savings. The net-present-value analysis indicates that the city should purchase the new street cleaner. The present value of the cost savings exceeds the new machine’s acquisition cost. Net-Present-Value Method Mountainview City Government Purchase of Street Cleaner (r = .10, n = 5) Step 1 Time 0 Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Time 4 Time 5 Acquisition Cost $(50,470) Annual cost savings $14,000 $14,000 $14,000 $14,000 $14,000 Step 2 Present value of annuity = $14,000(3.791) Annuity discount factor for r = .10 And n = 5 from Table 4 Present Value $(50,470) $53,074 Step 3 Net Present Value $2,604 Step 4 Accept proposal, since net present value is positive Internal-Rate-of-Return Method An alternative discounted-cash-flow method analyzing investment proposals is the internal-rate-of-return method. An asset’s internal-rate-of-return is the true economic return earned by the asset over its life. Another way of stating the definition is that an asset’s internal rate of return (IRR) is the discount rate that would be required in a net-present-value analysis in order for the asset’s net present value to be exactly zero. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 25

- 26. Chapter 16 Capital Expenditure Decisions: Introduction Edited by: I C C What is the internal rate of return on Mountainreview’s proposed street- cleaner acquisition? Recall that the asset has a positive net present value, given that the city’s cost of acquiring investment capital is 10 present. Would you expect the asset’s IRR to be higher or lower than 10 percent? Think about this question intuitively. The higher the discount rate used in a net-present-value analysis, the lower the present value of all the future cash flows will be. This is true because a higher discount rate means that it is even more important to have the money earlier instead of later. Thus, a discount rate higher than 10 percent would be required to drive the new street cleaner’s net present value down to zero. Finding the Internal Rate of Return: How can we find this rate? One way is trail and error. We could experiment with different discount rates until we find the one that yields a zero net-present value. We already know that a 10 percent discount rate yields a positive NPV. Let’s try 14 percent. Discounting the five-year, $14,000 cost-savings annuity at 14 percent yields a negative NPV of $2,408. (3.433)($14,000) - $50,470 = ($2,408) Annuity discount factor for r = 14 and n = 5. (From Table 4 ) What does the negative NPV at a 14 percent discount rate mean? We increased the discount rate too much. Therefore, the street cleaner’s internal rate of return must lie between 10 percent and 14 percent. Let’s try 12 percent: (3,605)($14,000) - $50,470 = 0 Annuity discount factor for r = 14 and n = 5. (From Table 4 ) That’s it. The new street cleaner’s internal rate of return is 12 percent. With a 12 percent discount factor, the investment proposal’s net present value is zero, since the street’s cleaner’s acquisition cost is equal to the present value of the cost savings. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 26

- 27. Chapter 17 Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions Edited by: I C C CHAPTER 17 COST ALLOCATION: A CLOSER LOOK After completing this chapter, you should be able to: Allocate service department costs using the direct method, step-down method, or reciprocal-service method. Use the dual approach to service department cost allocation Explain the difference between two-stage cost allocation with departmental overhead rates and activity-based costing. Describe the purposes for which joint cost allocation is used and those for which it is not. In earlier chapters we studied cost allocation and explored its role in an organization’s overall managerial- accounting system. We also examined several purposes of cost allocation. The goal of cost allocation is to ensure that all costs incurred by the organization ultimately are assigned to its products or services. In addition to that, the allocation of all costs to departments serve to make departmental managers aware of the costs incurred to produce services their department use. This chapter is divided into two sections, each of which explores a particular cost allocation topic in greater detail. These are: • Service department cost allocation • Joint product cost allocation Service Department Cost Allocation A service department is a unit in an organization that is not involved directly in producing the organization’s goods or services. However, a service department does provide a service that enables the organization’s production process to take place. For example, the Maintenance Department in an automobile plant does not make automobiles, but if it did not exist, the production process would stop when the manufacturing machines broke down. Service departments are important in nonmanufacturing organizations also. For example, a hospital’s Personnel Department is responsible for staffing the Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 27

- 28. Chapter 17 Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions Edited by: I C C hospital with physicians, nurses, lab technicians, and other employees without it the hospital would have no staff to provide medical care. A service department such as the Maintenance Department or the Personnel Department must exist in order for an organization to carry out its primary function. Therefore, the cost of running a service department is part of the cost incurred by the organization in producing goods or services. To see how service department cost allocation fits into the overall picture of product and service costing, it may be helpful to review the following three types of allocation processes: 1. Cost distribution. Cost in various cost pools are distributed to all departments, including both service and production departments. 2. Service department cost allocation. Service department costs are allocated to production departments 3. Cost application. Costs are assigned to the goods or services produced by the organization. It is the second type of allocation process listed above that we are focusing on now. The context for our discussion is Riverside Clinc. The clinc is organized into three service departments and two direct-patient- care departments as shown below. Since the clinic is not a manufacturing organization, we refer to direct-patient-care departments instead of production departments. These two departments, Orthopedics and Internal Medicine, directly provide the health care that is the clinc’s primary objective. Thus, the clinc’s direct-patient-care departments are like the production departments in a manufacturing firm. Organization Chart for Riverside Clinc EXHIBIT 1 Patient Personnel Admin/Acc. Records Department Department Service Department Departments Direct-patient-care Orthopedics Internal Department Department Medicine Department Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 28

- 29. Chapter 17 Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions Edited by: I C C Notice that the Personnel Department and the Administration and Accounting Department provide services to each other. When this situation occurs, the two service departments exhibit reciprocal services. EXHIBIT TWO provides some of the details of our illustration is consumed of service department cost allocation. Panel A shows the proportion of each of the departments using its services. Panel B shows the allocation bases, which are used to determine the proportion shown in panel A. Patient Records: The service output of the Patient Records Department is consumed only by the Orthopedic and Internal Medicine Department. Annual patient load is the allocation base used to determine that 30 percent of the Patient Records Department’s services were consumed by Orthopedics and 70 percent by Internal Medicine. Personnel: The Personnel Department serves each of the clinic’s other departments, including the other two service departments and the direct- patient-care departments. The allocation base used to determine the proportions of the Personnel Department’s. For example, 5 percent of the clinic’s employees (excluding those in the Personnel Department) work in the Patient Records Department. Administration and Accounting: This service department provides services only to the Personnel Department, the Orthopedics Department, and the Internal Medicine Department. A variety of services only to the Personnel Department, Orthopedics Department, and the Internal Medicine Department. A variety of services are provided, such as computer support, patient billing, and general administration. Since larger amounts of these services are provided to larger using departments, departmental size is the allocation base used to determine the proportion of service output consumed by each using department. EXHIBIT 2: Provision of Services by Service Departments User of Services Provider of Services Patient Recoder Personnel Administration Accounting Service Patient Recoder - 5% - Departments Personnel - - 5% Administration - 20% - Accounting Direct-care Orthopedics 30% 25% 35% departments Internal Medicine 70% 50% 60% (A) Percentage of Service output consumed by using departments Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 29

- 30. Chapter 17 Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions Edited by: I C C Service Department Allocation base Patient Records…………………………………………. Annual patient load Personnel ……………………………………………….. Number of employee Adminstration and Accounting ………………..……….. Size of Department (sq.m space) (B) Allocation bases Service Variable Cost Fixed Cost Total Cost to Be Departments Allocated Patient Recoder $24,000 $76,000 $100,000 Personnel 15,000 45,000 60,000 Administration Accounting 47,500 142,500 190,000 TOTAL $86,500 $263,500 $35,000 (C) Service department costs There are two widely used methods of service department cost allocation, the direct method and step-down method. These methods are discussed and illustrated next, using the data for Riverside Clinic. Direct Method Under the direct method, each service department’s costs are allocated among only the direct-patient-care that consume part of the service department’s output. This method ignores the fact that some service departments provide services to other service departments. Thus, even though Riverside Clinic’s Personnel Department provides services to two other service departments, none of its costs are allocated to these departments. Exhibit – 3 presents Riverside Clinic’s service department cost allocation under the direct method. Notice that the proportion of each service department’s costs to be allocated to each direct-patient-care department is determined by the relative proportion of the service department’s output consumed by each direct-patient-care department (see exhibit 2) Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 30

- 31. Chapter 17 Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions Edited by: I C C Step-Down Method As stated above, the direct method ignores the provision of services by one service department to another service department. This shortcoming is overcome partially by the step-down method of service department cost allocation. Under this method, the managerial accountant first chooses a sequence in which to allocate the service department’s costs. A common way to select the first service department in the sequence is to choose the one that serves the largest number of other service departments. The service departments are ordered in this manner, with the last service department being the one that serves the smallest number of other service departments. Then the managerial accountant allocates each service department’s costs among the direct-patient- care departments and all of the other service departments that follow it in the sequence. Note that the ultimate cost allocations assigned to the direct- patient-care departments will differ depending on the sequence chosen. Exhibit 3: Direct Method of Service Department Cost Allocation: Direct-Patient-Care Departments Using Service Provider of Cost to be Orthopedics Internal medicine Service Allocated Proportion Allocated Proportion Allocated Patient Records $100,000 3/10 $ 30,000 7/10 $ 70,000 Personnel 60,000 25/75 20,000 50/75 40,000 Administration and Accounting 190,000 35/95 70,000 60/95 120,000 TOTAL $350,000 $ 120,000 $230,000 Grand Total = $350,000 The step-down method is best explained by way of an illustration. Riverside Clinic’s Personnel Department serves two other service departments: Patient Records, and Administration and Accounting. The Administration and Accounting Department serves only one other service department: Personnel. Finally, the Patient Records Department serves no other service department. Thus, Riverside Clinic’s service department sequence is as follows: Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 31

- 32. Chapter 17 Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions Edited by: I C C (1) (2) (3) Personnel Administration Patient And Accounting Records In accordance with this sequence, each service department’s costs are allocated to the other departments as follows: Cost Allocated from To these Departments This Service Department Personnel……………………………………… - Administration/Accounting • Patient Records • Orthopedics • Internal Medicine Administration/ Accounting …………………. - Orthopedics • Internal Medicine Patient Records ………………………….…... - Orthopedics • Internal Medicine Note that even though Administration and Accounting serves Personnel, there is no cost allocation in that direction. This results from Personnel’s placement before Administration and Accounting in the allocation sequence. Moreover, no costs are allocated from Patient Records to either of the other service departments, because Patient Records does not serve those departments. Exhibit-4 presents the results of applying the step-down method at Riverside Clinic. First, the Personnel Department’s $60,000 in cost is allocated among the four departments using its services. Second, the cost of the Administration and Accounting Department is allocated. The total cost to be allocated is the department.s original $190,000 plus the the $12,000 allocated from the Personnel Department. The new total of $202,000 is allocated to the Orthopedics and Internal Medicine Departments according to the relative proportions in which these two departments use the services of the Adminstration and Accounting Department. Finally, the Patient Records Department’s cost is Allocated. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 32

- 33. Chapter 17 Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions Edited by: I C C Exhibit-4. Step-Down method of Service Department Cost Allocation: Riverside Clinic Service Departments Direct-Patient-Care Deparments Personnel Administration/ Patient Orthopedic Internal Accounting Records Records Costs prior $190,000 to allocation $60,000 $100,000 Allocation of Personnel $60,000 12,000 (20/100) $3,000 $15,000 (25/100) $30,000 (50/100) Department costs (5/100) Allocation of Administration/Acc. $202,000 $74,421 (35/95) $127,579 (60/95) Department costs Allocation of Patient Records $103,000 $30,900 (30/100) $72,100 (70/100) Department costs Total cost allocated to each department $120,321 $229,679 Total cost allocated to direct-patient-care departments = $ 350,000 SECTION TWO: Joint Product Cost Allocation A joint production process results in two or more products, which are termed joint products. The cost of the input and the joint production process is called a joint product cost. The point in the production process where the individual products become separately identifiable is called the split-off point. To illustrate, International Chocolate Company produces cocoa powser and cocoa butter by processing cocoa beans in the joint production process shown exhibit-5. As the diagram shows, cocoa beans are processed in 1-ton batches. The beans cost $500 and the joint process costs $600, for a total joint cost of $1,100. The process results is 1,500 kgs of cocoa butter and 500 kgs of cocoa powder. Each of these two joint products can be sold at the split-off point or processed further. Cocoa butter can be separately processed into the instant cocoa mix. …. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 33

- 34. Chapter 17 Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions Edited by: I C C Cocoa butter Separable Tanning cream sales value: process sales value: $750 for costing $3,000 for 500 1,500 kgs $1,560 kgs Cocoa beans costing $500 Joint production per 1 ton process costing Cocoa Separabl Instant cocoa batch $600 per ton powder sales e process mix sales value: $500 costing value: $2,000 for 500 kgs $800 for 500 kgs Total joint cost: $1,100 per 1 ton batch Physical-Units Method: This method allocates joint product costs on the basis of some physical characteristic of the joint products at the split-off point. Panal A of exhibit 6 illustrates this allocation method for International Chocolate Company using the weight of the joint products as the allocation basis. Relative-Sale-Value Method: This approach to joint cost allocation is based on the relative sales value of each joint product at the split-off point. In the International Chocolate Company illustration, these joint products are cocoa butter and cocoa powder. This method is illustrated in Exhibit 6 (panel B) Net-Realizable-value Method: Under this method, the relative value of the final products is used to allocate the joint cost. International Chocolate Company’s final products are tanning cream and instant cocoa mix. The net realizable value of each final product is its sales value less any separable costs incurred after the split-off point. The joint cost is allocated according to the relative magnitudes of the final product’s net realizable values. Panel C of Exhibit 6 illustrates this allocation method. Notice how different the cost allocations are under the three methods, particularly the physical-units method. Since the physical-units approach is not based on the economic characteristics of the joint products, it is the least preferred of the three methods. Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 34

- 35. Chapter 17 Further Aspects of Capital Expenditure Decisions Edited by: I C C EXHIBIT 6: Methods for Allocating Joint Product Costs Joint Joint Weight at Relative Allocation of Cost Product Split-off Point Preportion Joint Cost Cocoa butter ……. 1,500 kgs……….……. ¾ ……………………..$ 825 $1,100 Cocoa powder……. 500 kgs…………… 1/4 ……………………. 275 Total joint cost allocated…………………………… ………….……… $ 1,100 (A) Physical-unit method Joint Joint Sales Value at Relative Allocation of Cost Product Split-off Point Proportion Joint Cost Cocoa butter ………. $750…………. ………. 3/5 …………………….. $660 $1,100 Cocoa Powder………. 500 ………………..… 2/5 ……………………… 440 Total joint cost allocated…………………………….………………… $ 1,100 (B) Relative-sales-value method Sales Value Separable Net Joint Joint of final Cost Realizable Relative Allocation of Cost Product product Processing Value Proportion joint Costs Cocoa butter $3,000 $1,560 $1,440 6/11 $600 $1,100 Cocoa Powder 2,000 800 1,200 5/11 500 Total joint cost allocated…………………………………………….. $1,100 (C) Net-realizable-value method * Sales value of separable cost Net Calculating of relative proportions: final product - of processing = realizable $1,440 + $1,200 = $2,640 value $1,000 - $1,500 = $1,440 (1,440 + 2,640) = 6/11 2,000 - 800 = 1,200 (1,200 + 2,640) = 5/11 Prepared by: Prof. Shirdon, Edited & Printed by: SAHAL Stationery 4455061/9255353 Page 35