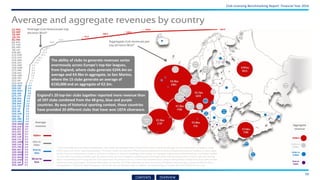

This document provides an overview and analysis of the European club football landscape based on data from the 2016 financial year. It covers various topics related to domestic competitions, supporters, ownership, sponsorship, transfers, wages, profitability, and balance sheets. Some of the key findings presented include that European clubs together generated the highest operating profits before transfers in history in 2016 and nearly 10% annual revenue growth. Club investments in stadiums and infrastructure exceeded €1 billion for the first time. However, the report also notes increasing financial polarization, with the top 12 clubs generating a dramatic increase in commercial revenues that is more than double the combined increase of all other European clubs.