5262020 Innovation Process Design Scoring Guidehttpsc.docx

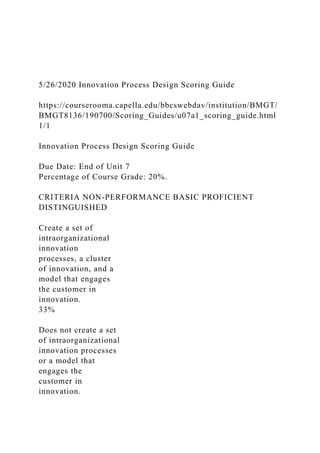

- 1. 5/26/2020 Innovation Process Design Scoring Guide https://courserooma.capella.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/BMGT/ BMGT8136/190700/Scoring_Guides/u07a1_scoring_guide.html 1/1 Innovation Process Design Scoring Guide Due Date: End of Unit 7 Percentage of Course Grade: 20%. CRITERIA NON-PERFORMANCE BASIC PROFICIENT DISTINGUISHED Create a set of intraorganizational innovation processes, a cluster of innovation, and a model that engages the customer in innovation. 33% Does not create a set of intraorganizational innovation processes or a model that engages the customer in innovation.

- 2. Creates limited elements of intraorganizational innovation processes, clusters of innovation, and a model that engages the customer in innovation. Creates a set of intraorganizational innovation processes, a cluster of innovation, and a model that engages the customer in innovation. Creates with exceptional clarity intraorganizational innovation processes, a cluster of innovation, and a model that engages the customer in innovation. Provides strong synthesis of theories, comparing and contrasting the concepts. Apply the concepts of the intraorganizational innovation processes, a cluster of innovation, and a

- 3. model that engages the customer in innovation to a for- profit publicly traded organization. 33% Does not apply the concepts of the intraorganizational innovation processes, a cluster of innovation, or a model that engages the customer in innovation to a for- profit publicly traded organization. Partially applies the concepts of the intraorganizational innovation processes, a cluster of innovation, and a model that engages the customer in innovation to a for- profit publicly traded organization. Applies the concepts of the intraorganizational innovation processes, a cluster

- 4. of innovation, and a model that engages the customer in innovation to a for- profit publicly traded organization. Applies the concepts of the intraorganizational innovation processes, a cluster of innovation, and a model that engages the customer in innovation to a for-profit publicly traded organization. Communicate in a manner expected of doctoral-level composition, including full APA compliance and demonstration of critical thinking skills. 34% Fails to communicate in a manner expected of doctoral- level composition; assignment has gaps in APA compliance and in demonstration of critical thinking skills.

- 5. Communicates at a basic level expected of doctoral-level composition, including partial APA compliance and demonstration of critical thinking skills. Communicates in a manner expected of doctoral-level composition, including full APA compliance and demonstration of critical thinking skills. Communicates exceptionally well in a manner expected of doctoral-level composition, including full APA compliance and demonstration of exceptional critical thinking skills. 16 Journal of Marketing

- 6. Vol. 75 (January 2011), 16 –30 © 2011, American Marketing Association ISSN: 0022-2429 (print), 1547-7185 (electronic) V. Kumar, Eli Jones, Rajkumar Venkatesan, & Robert P. Leone Is Market Orientation a Source of Sustainable Competitive Advantage or Simply the Cost of Competing? The authors use panel data constructed from the responses of repeatedly surveyed top managers at 261 companies regarding their firm’s market orientation, along with objective performance measures, to investigate the influence of market orientation on performance for a nine-year period from 1997 to 2005. The authors measure market orientation in 1997, 2001, and 2005 and estimate it in the interval between these measurement periods. The analyses indicate that market orientation has a positive effect on business performance in both the short and the long run. However, the sustained advantage in business performance from having a market orientation is greater for the firms that are early to develop a market orientation. These firms also gain more in sales and profit than firms that are late in developing a market orientation. Firms that adopt a market orientation may also realize additional benefit in the form of a lift in sales and profit due to a carryover effect. Market orientation should have a more pronounced effect on a firm’s profit than sales because a market orientation focuses efforts on customer retention rather than on acquisition. Environmental turbulence and competitive intensity moderate the main effect of market orientation on business performance, but the moderating effects are greater in the 1990s than in the

- 7. 2000s. Keywords: market orientation, customer relationship management, longitudinal, sustainable competitive advantage, business performance V. Kumar is Richard and Susan Lenny Distinguished Chair in Marketing and Executive Director of the Center for Excellence in Brand & Customer Management, J. Mack Robinson School of Business, Georgia State Uni- versity (e-mail: [email protected]). Eli Jones is Dean and E.J. Ourso Distinguished Professor, E.J. Ourso College of Business, Louisiana State University (e-mail: [email protected]). Rajkumar Venkatesan is Bank of America Professor in Marketing, Darden Graduate School of Business, University of Virginia (e-mail: [email protected]). Robert P. Leone is a professor and J. Vaughn and Evelyne H. Wilson Chair of Marketing, Neeley School of Business, Texas Christian University (e-mail: [email protected]). All authors contributed equally. The authors thank Ed Blair, Ruth Bolton, Steve Brown, Lawrence Chonko, Partha Krishna- murthy, Stanley Slater, Dave Stewart, and the three anonymous JM reviewers for their comments on previous versions of this article. Roger Kerin served as guest editor for this article. As businesses become increasingly competitive, mar- keters must identify routes for improved measurement of

- 8. [investments in marketing activities]. (Scase 2001, p. 1) D ynamism in business environments caused by eco- nomic slowdown or growth, competitive intensity, globalization, mergers and acquisitions, and rapid- fire product and technological innovations challenges top managers’ ability to sense and respond to market changes accurately. The inability to sense and respond to market changes quickly has led to the demise of many firms with household names, including Kmart and Circuit City. There- fore, it is critical that managers identify and understand strategic orientations that enable a firm to sustain perfor- mance, especially in the presence of rapid changes in mar- ket conditions. The marketing concept that has existed for many years was one of the first strategic frameworks that provided firms with a sustainable competitive advantage (SCA). Aca- demics first began recognizing and operationalizing the marketing concept as “market orientation” in the 1990s (Kohli and Jaworski 1990). During the past 20 years, hun- dreds of articles have been published on market orienta- tion’s effect on business performance (Kirca, Jayachandran, and Bearden 2005). However, few studies have investigated the longer-term benefits of market orientation (for excep- tions, see Gebhardt, Carpenter, and Sherry 2006; Noble, Sinha, and Kumar 2002), and almost nothing has been pub- lished on this relationship using longitudinal data. This is an important gap because obtaining business sustainability remains a key concern for senior managers. Thus, a replica- tion and extension of prior work is needed, using a longer horizon to validate the full extent of market orientation’s time-varying effect on business performance. Therefore, in

- 9. this study, we use existing measures from the literature to assess the performance of market orientation on long-term business performance. Our two specific questions are as fol- lows: (1) Does market orientation create a source of SCA, or is it a requirement that companies face when competing in today’s business environment? and (2) How much is gained, and how long can firms expect the advantages from developing a market orientation to hold? Market Orientation and Long-Term Performance The literature suggests that market orientation’s primary objective is to deliver superior customer value, which is based on knowledge derived from customer and competitor analyses and the process by which this knowledge is gained and disseminated throughout the organization (e.g., Felton 1959; Narver and Slater 1990). A superior understanding of customer needs, competitive actions (i.e., industry structure and positional advantages), and market trends enables a market-oriented firm to identify and develop capabilities that are necessary for long-term performance (Day 1994). Investments in capabilities, such as active information acquisition through multiple channels (e.g., sales force, channel partners, suppliers), incorporation of the customer’s voice into every aspect of the firm’s activities, and rapid sharing and dissemination of knowledge of the firm’s cus- tomers and competition, take time to provide returns. For example, investments in improving customer satisfaction affect firm performance through improved customer reten- tion and profitability. However, these benefits from improv- ing customer satisfaction are more likely to be observed in the long run than in the short run.

- 10. Market orientation is a capability and the principal cul- tural foundation of learning organizations (Deshpandé and Farley 1998; Slater and Narver 1995). Through constant acquisition of information regarding customers and compe- tition and the sharing of this information within an organi- zation, market-oriented firms are well positioned to develop an organizational memory, a key ingredient for developing a learning organization. Furthermore, a market orientation encourages a culture of experimentation and a focus on con- tinuously improving the firm’s process and systems. This implies that developing and improving on a firm’s market orientation may make a firm’s capabilities become more distinctive (relative to the competition) over the long run, resulting in SCA. There are also reasons to believe that market orientation may not provide an SCA. First, a market orientation may lead a firm to narrowly focus its efforts on current cus- tomers and their stated needs (i.e., adaptive learning versus generative learning; Hamel and Prahlad 1994; Slater and Narver 1995). Such a narrow focus could lead to market- oriented firms not anticipating threats from nontraditional sources, thus restricting a market orientation’s capability to provide an SCA. Second, and most important, a market ori- entation can provide long-term performance benefits if it is not imitable by the competition. Capabilities and processes are not imitable if they provide firms with tacit knowledge that enables them to understand customers’ latent needs (Day 1994). However, such a tacit knowledge base is devel- oped only if firms adopt a broader and more proactive approach to market orientation (Slater and Narver 1998). Finally, it is widely accepted that a firm’s only sustainable advantage is its ability to learn and anticipate market trends faster than the competition (De Geus 1988). Again, the majority of the published empirical support for

- 11. the benefits of market orientation is based on cross-sectional databases. Therefore, our knowledge is limited to market Market Orientation and Sustainable Competitive Advantage / 17 orientation’s influences on static measures of performance. Cross-sectional databases cannot control for potentially unobservable, firm-specific effects and cannot uncover the time-varying effects of market orientation. For example, Gauzente (2001) suggests that there are three aspects of time that affect market orientation and its impact on perfor- mance: (1) lagged, (2) threshold, and (3) cumulative effects. Therefore, empirical studies examining market orientation’s influence on business performance over time would provide a more complete view of the benefits associated with devel- oping and improving a market orientation. The few longitu- dinal studies that exist show no long-term relationship between market orientation and return on investment, which indicates that a market orientation may be too costly and that the returns are not large enough to justify the cost of implementation (Narver, Jacobson, and Slater 1999). In summary, the ability of market orientation to provide an SCA is still unresolved, because the evolutionary nature of a market orientation–performance relationship has not been satisfactorily addressed. In this study, we treat a mar- ket orientation–performance relationship more realistically and more fully as an unfolding process rather than a dis- crete event. Our longitudinal study design enables us to pro- vide further insights into the dynamic nature of market ori- entation’s effect on business performance. Effect of Competition Prior theoretical and empirical research has investigated the effect of market orientation of a firm independent of the ori- entation of the competitors in the industry. Thus, a funda-

- 12. mental question regarding market orientation still remains unanswered: Does a market orientation still provide a competitive advantage if the firm’s competitors are also market oriented? In other words, as more firms in an indus- try become market oriented, does a firm’s market orienta- tion transform from being a success provider to being a fail- ure preventer? That is, do moderate or high levels of effort to maintain a market orientation only prevent failure and not necessarily improve performance (Varadarajan 1985)? Related to this, firms investing in developing a market orientation want to know the advantages obtained from being the first to adopt a market orientation in an industry. Early adopters of market orientation can obtain insights into customer needs before the competition. Responding to these customer insights through the development of product or service innovations can provide firms with improved business performance. However, rarely is a product or ser- vice safe from imitation by competition. Furthermore, com- petitors can develop their own system and culture of being market oriented and can potentially change the market struc- ture as well. For example, pharmaceutical companies derive competitive advantages while their products are under exclusive patents, which provides them lead time in devel- oping SCA while they recoup research-and-development costs. However, competitors often develop and patent “similar” formularies, which could lead to industry equilib- rium. An example in the technology industry is the compe- tition between IBM and Hewlett-Packard. Although IBM pioneered the concept of a single firm providing hardware, software, and services, which provided lead time in devel- oping an SCA, Hewlett-Packard matched this concept even- tually and surpassed IBM in becoming the largest informa-

- 13. tion technology firm in the world. Using a unique panel data set obtained from (1) repeated surveys of top managers regarding their market orientation and (2) objective measures of business perfor- mance, we provide empirical evidence for first-adopter advantages with regard to developing a market orientation. Our study offers new insights at a critical time in business history by more fully explicating market orientation’s influ- ence on business performance. We examine the business performance–market orientation relationship and investi- gate whether it has changed over the 1997–2005 period. This gives us a view of the short-term and long-term effects of having a market orientation. It also enables us to deter- mine whether these effects have changed over the nine years under study. In this study, we refer to the effect of market orientation in a particular year on business perfor- mance in that year (i.e., the current or contemporaneous effect) as the short-term effect of market orientation. The long-term effect refers to the cumulated effect of market orientation from the prior years on business performance in a particular year and includes the current period’s effect of market orientation. To be consistent with prior studies and avoid model misspecification, we also include environmental variables (turbulence and competitive intensity) as moderators of the relationship between market orientation and business per- formance, and we examine these effects over a longer period than prior studies. Including the environmental mod- erators enables us to evaluate whether market orientation is a source of SCA when rapid changes occur in market con- ditions. As Figure 1 illustrates, use of these panel data per- 18 / Journal of Marketing, January 2011

- 14. taining to market orientation, environmental moderators, and business performance enables us to assess the evolving nature of market orientation on business performance. Fig- ure 1 depicts the relationships that we test in this study. Our analyses indicate that market orientation had a posi- tive effect on business performance in both the short and the long run. However, the sustained advantage in business per- formance from having a market orientation was greater for the first (early) adopters in an industry. The firms that were early to develop a market orientation gained more in sales and profit than firms that were late to develop a market ori- entation. Furthermore, firms that adopted a market orienta- tion early also realized the benefit of a bonus in the form of a lift in sales and profit due to a carryover effect that lasted up to three periods. By computing measures of elasticity, it is possible to assess whether market orientation has a more pronounced effect on a firm’s profit than sales. Because market orientation focuses a firm’s efforts on customer retention rather than on acquisition, market orientation should give a greater lift to profit than to sales. Environ- mental turbulence and competitive intensity moderated the main effect of market orientation on business performance, but the moderating effect was greater in the 1990s than in the 2000s. Devoting resources to market orientation can be a costly and slow process. Thus, in addition to testing theory, the research findings are useful to managers who are reevaluat- ing their decision to continue investing in building market- oriented organizations. A long-term view reinforces the impact of implementing and maintaining a market orienta- tion on sustained improvements in business performance. Our study contributes to the literature by evaluating, for the first time, (1) the long-term effects of market orientation on sales and profit, (2) the effect of competition over time on

- 15. FIGURE 1 Market Orientation on Business Performance over Time: Main and Contingent Effects Market Orientation Early Adopter Market Orientation Midterm Adopter Market Orientation Late Adopter Industry- and Firm- Specific Factors Environmental Factors (over Time) Business Performance (over Time) Market and technological

- 16. turbulence Competitive intensity Sales Profitability the relationship between market orientation and a firm’s business performance, and (3) the time-varying effects of the previously studied moderators on a market orientation– business performance relationship. In the sections that fol- low, we review the existing literature, propose and test hypotheses arising from our review, discuss the empirical findings, and state several managerial implications. Conceptual Background and Hypotheses Market Orientation as a Potential Source of SCA Market orientation is the generation and dissemination of organizationwide information and the appropriate responses related to customer needs and preferences and the competi- tion (Kohli and Jaworski 1990). A market orientation posi- tions an organization for better performance because top management and other employees have both information on customers’ implicit and expressed needs and competitors’ strengths and a strong motivation to achieve superior cus- tomer satisfaction (e.g., Pelham 1997). These capabilities can be transformed into an SCA when a firm uniquely has the information and uses the market information efficiently and effectively as part of a process. During the past few

- 17. years, organizations have embraced a market orientation concept and its purported benefits, which has created an intensely competitive landscape. What happens, then, when the competition is also market oriented? It is important to note that though several valid operationalizations of market orientation exist (for details, see Deshpandé, Farley, and Webster 1998), we follow the capabilities-based definition that Jaworski and Kohli (1993) propose. Empirical Evidence of a Market Orientation– Business Performance Link Main effects. Prior research has illustrated that a high degree of market orientation in an organization leads to short-term improvements in sales and profitability growth, market share, new product success, customer satisfaction, and return on assets, compared with other organizations that are not as highly market oriented (Deshpandé, Farley, and Webster 1993; Jaworski and Kohli 1993; Slater and Narver 1994). At the same time, market orientation is not associ- ated with superior performance after a crisis (Grewal and Tansuhaj 2001), in the theater industry (Voss and Voss 2000), and in the retail industry (Noble, Sinha, and Kumar 2002). The vast literature regarding the positional advantages of first (early) adopters and the capabilities of later entrants is relevant to our study. Organizational innovations such as market orientation provide more durable cost and differenti- ation advantages than product or process innovations (Lieberman and Montgomery 1988). Firms that are first to adopt a market orientation tend to be more capable of iden- tifying customer needs that are unmet in their industry and respond by developing new products or services. They may also enjoy greater elasticity from their marketing efforts because there is less clutter for the new products or ser-

- 18. vices, providing a cost advantage for the pioneering market- Market Orientation and Sustainable Competitive Advantage / 19 oriented firm. Over time, the acquired customers develop switching costs, which lead to higher customer retention and a differential advantage for the pioneering market-oriented firm (Kerin, Varadarajan, and Peterson 1992). However, a market orientation may also provide a competitive advantage only as long as this capability is dis- tinct in the market. The pioneering market-oriented firm’s competitive advantage is ultimately contingent on its other skills and resources (e.g., distribution capability, research- and-development expertise), the competitors’ strategy, and changes in the environment (Lieberman and Montgomery 1990). Firms that are later adopters of market orientation can also learn from the pioneer’s mistakes and therefore be more effective and efficient in (1) developing market-oriented capabilities in their organizations and (2) responding to cus- tomer needs. Market orientation is an ongoing effort, and firms can increase their level of market orientation in response to competition or later adopters of market orientation. How- ever, there is little guidance in the literature on whether threshold effects to being market oriented exist. One view on market orientation is that firms may narrowly define existing customers as their served market, and in this case, a market orientation may be detrimental to the firm. It is also possible that, over time, as other firms adopt a market ori- entation, market orientation transforms from being a suc- cess provider to being a failure preventer (Varadarajan 1985). In other words, there may be thresholds beyond which further focus on and improvements to market orien- tation do not provide corresponding returns in profit and

- 19. sales. This diminishing effect may also arise when cus- tomers begin to expect a certain level of product value and service quality from market-oriented firms. This could lead to a reduced marginal effect of market orientation on busi- ness performance in the long run. Therefore, balancing the positional advantages of the first (early) adopters of market orientation and the capabilities and efficiencies that are pos- sible for later adopters, we propose the following: H1: The relationship between (a) market orientation and sales and (b) market orientation and profit is initially positive, but this effect decreases over time. Day and Wensley (1988) purport that investigating the moderating influence of the industry environment on a mar- ket orientation–performance relationship is of paramount importance, and thus marketing researchers have pursued external environmental factors and acknowledged that they can moderate market orientation’s effect on business perfor- mance (Gatignon and Xuereb 1997; Greenley 1995; Grewal and Tansuhaj 2001; Han, Kim, and Srivastava 1998; Jaworski and Kohli 1993; Slater and Narver 1994; Voss and Voss 2000). Similar to the main effects, previous research has investigated only the short-term moderating effects of environmental factors on a market orientation–business per- formance relationship. We extend prior literature by provid- ing theoretical arguments for the effects of environmental conditions on a market orientation–performance relationship over time. The moderators in our study follow the defini- tions that Jaworski and Kohli (1993) posit. Market orientation and market turbulence. Garnering knowledge from retained customers about their preferences (and needs) and maintaining a learning orientation are charac-

- 20. teristics of market-oriented organizations. When marketers understand how much a given customer might be worth to the organization over time, they can tailor the product/service offering according to that customer’s changing needs and requirements and still ensure an adequate lifetime return on investment (Berger et al. 2002). Therefore, market-oriented organizations are capable of better customer retention (Narver, Jacobson, and Slater 1999). These resources lead to better performance in the long run, especially in highly turbulent markets in which customer preferences are con- stantly changing. Similar to the rationale for the main effects, we propose that as more firms become market oriented, the capability of a particular market-oriented organization is no longer unique, because customers begin to expect a certain quality of products and services from market-oriented firms. Fur- thermore, the benefit market-oriented firms obtain in turbu- lent markets is diminished when competitors are also mar- ket oriented. Together, these effects lead to a diminishing effect of market orientation on business performance over time. As more firms in an industry become market oriented, each of them is capable of delivering value and retaining customers even when the customers’ needs are constantly changing. Economic theory has found similar “stability in competition” effects over time as markets reach equilibrium (Hotelling 1929). Therefore, the moderating effect of mar- ket turbulence is diminished over time. Although a market- oriented firm still has better performance in markets with greater turbulence than those that are more stable, this incremental benefit decreases over time. Thus: H2: Market turbulence positively moderates the relationship between (a) market orientation and sales and (b) market orientation and profit, but this positive moderating effect diminishes over time.

- 21. Market orientation and technological turbulence. On the basis of the theoretical arguments advanced in prior research, we hypothesize that, initially (i.e., in the 1990s), a high level of technological turbulence diminished the influ- ence of market orientation on growth in sales and profit. In markets with high technological turbulence, the characteris- tics of products and services are largely determined by innovations both within and outside the industry. In such cases, a learning orientation and knowledge about customer preferences do not necessarily contribute initially to long- term performance. Before the late entrants also become market oriented, technological turbulence is especially dis- advantageous for the early adopters of market orientation because the other firms are more receptive to technological trends than market-oriented firms (Slater and Narver 1994). However, as more firms become market oriented in an industry, both the early and the late adopters are equally dis- advantaged in markets with high levels of technological tur- bulence. Although market-oriented firms perform worse in markets with high technological turbulence than in those with less volatility in technology, the disadvantage dimin- ishes over time. Thus: 20 / Journal of Marketing, January 2011 H3: Technological turbulence negatively moderates the rela- tionship between (a) market orientation and sales and (b) market orientation and profit, but this negative moderating effect diminishes over time. Market orientation and competitive intensity. In the absence of competition, customers are “stuck” with an orga- nization’s products and services. In contrast, under conditions of high competitive intensity, customers have many alterna- tive options to satisfy their needs and requirements. Over

- 22. time, however, competitive intensity can enhance the effects of market orientation on performance as market-oriented firms in the same industry increase their capabilities and processes (e.g., optimal resource allocation) to retain key customers. In effect, this creates quasi “barriers to entry” for other competing firms that are not market oriented. Highly market-oriented firms are also uniquely capable of responding to and preempting competitive threats in a timely manner, which facilitates the attainment of higher sales and profit. Thus, in highly competitive markets, the companies with a greater market orientation are capable of better performance. However, the moderating effect of competitive intensity decreases as more firms in an industry become market ori- ented. In other words, the incremental benefit of being an early adopter of market orientation decreases over time. When the late entrants also become market oriented, every firm is capable of understanding the strengths of its compe- tition and anticipating competitive moves. This enables each firm to provide differentiated value to its customers, thus ensuring customer retention and profitability. This notion implies that a high degree of competition equally benefits all the firms in the industry. Therefore, the moder- ating effect of competitive intensity should decrease over time. Thus: H4: Competitive intensity positively moderates the relation- ship between (a) market orientation and sales and (b) mar- ket orientation and profit, but this positive moderating effect diminishes over time. We submit these hypotheses to empirical tests using panel data analytics on data gathered through multiple sources. We used subjective and objective data to uncover the effects of market orientation levels on short- and long-

- 23. term sales and profit. Methodology Measures Market orientation and environmental moderators. We measured market orientation and environmental moderators using the scales Jaworski and Kohli (1993) developed. For each component, we used the mean value of all the items listed under the respective component for the analyses. Business performance. Our study includes sales and net income in a single study. Often, firms exhibit differential effects on these two performance measures. We obtained the objective measures of sales and net income (pure profit after sales) from multiple sources, including annual reports; publications, such as Beverage World and The Wall Street Journal; and industry reports. We also obtained subjective measures of performance on both net income and sales from the responding firms. Following Jaworski and Kohli’s (1993) approach, we measured subjective performance on a five-point scale ranging from “excellent” to “poor.” The items we used to measure subjective performance include “Your overall performance of the firm/business unit with respect to net income in the year … was?” and “Your over- all performance of the firm/business unit relative to major competitors with … Integrating Customers in Product Innovation: Lessons from Industrial

- 24. Development Contractors and In-House Contractors in Rapidly Changing Customer Marketscaim_555 89..106 Patricia Sandmeier, Pamela D. Morrison and Oliver Gassmann Successful product innovation has increasingly been recognized as an outcome of integrating customers into the new product development (NPD) process. In this paper, we explore cus- tomer integration by investigating the continual consideration of customer contributions throughout the product innovation process. Through a comparison of the customer integration practices by development contractors with those of in-house developers, we find that the iterative and adaptive innovation process structures of the development contractors facilitate the realization of the full customer contribution potential throughout the product innovation process. We also find additional support for the incorporation of open innovation into an organization’s NPD activities. Our findings are based on in- depth case studies of the NPD activities of in-house developers and product development contractors. 1. Introduction The positive impact of customer integrationon product innovations has long been acknowledged. Empirical research shows that the integration of customer contributions in new product development (NPD) leads to a higher degree of product newness, reduced

- 25. innovation risks and more precision in resource spending (Gupta, Raj & Wilemon, 1986; Kohli & Jaworski, 1990; Bacon et al., 1994; Millson & Wilemon, 2002; Brockhoff, 2003; Callahan & Lasry, 2004). In particular, the value of lead users has been demonstrated by various researchers: the value of product innovation increases when users bring their specialized knowledge of needs, preferences and solutions to NPD, leading to new prod- ucts that provide true value to customers (von Hippel, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1988; Herstatt & von Hippel, 1992; Lilien et al., 2002; Morrison, Roberts & Midgley, 2004; Lüthje, Herstatt & von Hippel, 2005). Most work in this field focuses on approaches in which customer integration stands for a better understanding of custom- ers’ initial product requirements. These ap- proaches include ‘market orientation’ (Kohli & Jaworski, 1990; Atuahene-Gima, 1996), the ‘voice of the customer’ (Griffin & Hauser, 1993), the ‘virtual customer’ (Paustian, 2001; Dahan & Hauser, 2002), ‘customer driven innovation’ (Billington, 1998), or ‘consumers as co-developers’ (Jeppesen & Molin, 2003). With this understanding, the customers’ contribu- tions can be brought into R&D directly or through the marketing department to develop new products that fit customers’ real needs and wishes (von Hippel, 1978; Griffin & Page, 1996; Berry & Parasuraman, 1997; Dahan & Hauser, 2002; von Hippel & Katz, 2002). In this paper, we explore customer integra-

- 26. tion by investigating the continual consider- ation of customer contributions throughout the product innovation process. We compare the practices of development contractors – i.e., professional technical service firms that INTRGRATING CUSTOMERS IN PRODUCT INNOVATION 89 Volume 19 Number 2 2010 doi:10.1111/j.1467-8691.2010.00555.x © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd innovate on a contract basis – with that of in-house developers. The technical service firms develop new products with a very high success rate but with different organizational structures and processes compared to tradi- tional in-house developers. We chose this com- parison in order to reveal the factors on which the development contractors’ success is based. We find that their iterative and adaptive innovation process structures facilitate the realization of the full customer contribution throughout the product innovation process. The question of how customers can contrib- ute to product innovation activities and how and where their contribution can be built into the NPD process to take advantage of the full customer integration potential has not previ- ously been addressed. We contribute to close a theoretical gap by showing that a continuous

- 27. consideration of customer contributions throughout the product innovation process requires a recurring pattern of accessing, releasing and absorbing customer contribu- tions. This insight helps answer how innova- tion capabilities from outside the R&D department can be capitalized. The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides the theoretical background from existing literature; Section 3 develops the framework which guides the comparison between the practices applied by development contractors with those of in-house developers; Section 4 introduces our research methodol- ogy; Section 5 presents the results from the case study comparison, leading to four research propositions; and in Section 6 we discuss the implications of our research find- ings. We conclude with limitations and recom- mendations for further critical and practical work. 2. Research Background In environments where requirements can be highly uncertain, changing customer needs have to be faced for the development of indus- trial products. Experimental NPD methodolo- gies tolerating these changes were found to be the only ones capable of bringing out innova- tive new products in the required period of time (Lynn, Morone & Paulson, 1996). Since existing change-oriented approaches focus on the ability to learn and share information quickly (Zahay, Griffin & Fredericks, 2004), we

- 28. focus on organizational learning theory to guide us as a theoretical starting point. Organizational learning is defined as the process of improving actions through better knowledge and understanding (Fiol & Lyles, 1985). Applying this definition to the research terrain of customer integration, learning from customers throughout the development of new products implies that the company learns about its market through a series of sequential information processing activities undertaken with its customers (Kok, Hillebrand & Biemans, 2003). Learning about markets for new products can be understood as an organi- zational learning process that involves the acquisition, dissemination and utilization of information (Fiol & Lyles, 1985; Imai, Ikujiro & Takeuchi, 1985; Huber, 1991; March, 1991). First, acquiring market information consists of the collection of information about the needs and behaviour of customers. Some of this information can be obtained from data banks and the results of past actions, whereas some needs to be collected anew through quantita- tive (e.g., market surveys) or qualitative (e.g., customer visits) methods (Adams, Day & Dougherty, 1998). Second, market information has to be disseminated across functions, phases of the innovation process, geographic boundaries and organization levels (Adams, Day & Dougherty, 1998). Third, using market information occurs in the process of learning about the market for decision making, the implementation of decisions, or evaluations of

- 29. a new product (Menon & Varadarajan, 1992). We use the constructs from learning theory – acquisition, dissemination and utilization – to structure a literature review on integrating customers into NPD. Acquisition of Knowledge To profit from customer know-how, this know-how first has to be acquired. Literature on integrating customers emphasizes the choice of the right partner from whom the required information can be obtained as a core aspect of interacting with customers (Gruner & Homburg, 2000). Biemans (1992) states that the identity of the customers employed typi- cally varies with the extent and intensity to which the customer is involved, as it does with the stage of the NPD process. Gruner and Homburg (2000) identified three different characteristics of valuable co-operation partners for NPD: financial attractiveness, closeness of customers and the lead user characteristics. First, customers’ financial attractiveness relates to their repre- sentativeness of the target market and their reputation within that market (Ganesan, 1994). The second characteristic is the closeness of the relationship between the developing company and the customer, including the level of interaction outside the respective innovation project and the duration of the business rela- tionship (Doney & Cannon, 1997). Lead users,

- 30. 90 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT Volume 19 Number 2 2010 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd as defined by von Hippel (1986, 1988), combine two characteristics: they expect attractive innovation-related benefits from a solution to their needs and so are motivated to innovate, and they experience needs for a given innovation earlier than the majority of the target market. Von Hippel (1986) proposed and Urban and von Hippel (1988) tested the proposition that idea-generation studies can learn from lead users, both within and well beyond intended target markets – lead users found outside the target market often encoun- ter even more extreme conditions on a trend relevant to that target market. Their positive impact on product innovations has since been demonstrated by several studies (Herstatt & von Hippel, 1992; Lilien et al., 2002; Lüthje & Herstatt, 2004). Dissemination of Knowledge The imperative of opening up the NPD process has been discussed within open innovation research (Chesbrough, 2003; Gassmann, 2006). This openness should enable organizations to react to significant changes which occur in rapidly changing markets in both customer needs and technological potentials during the NPD process. This can be done through

- 31. experimentation by providing toolkits (von Hippel & Katz, 2002) or early versions of pro- totypes of the product under development to the customer for feedback on a regular basis (Thomke, 1998, 2001). Thomke’s work points out the relevance of prototypes – or, more generally – the visual- ization media for transferring the project to the customer site and to release customers’ contri- butions. Visualization through paper concepts, mock-ups, rapid prototyping and computer aided design can help in information sharing and building consensus over the course of a development project (Terwiesch & Loch, 2004; Veryzer & Borja de Mozota, 2005). Physical representation of the product under develop- ment at different points of the NPD process help to create a common understanding of development issues which may arise accord- ing to the different vocabularies and environ- ments the involved stakeholders come from. Utilization of Knowledge The best possibility to utilize customer contri- butions is generally seen in the early phases of the product innovation process, the so-called innovation front-end or product definition phase (Murphy & Kumar, 1997; Kim & Wilemon, 2002). Approaches such as the Stage- Gate™ model of innovation (Cooper & Klein- schmidt, 1986; Cooper, 1994) can be very useful; however, they have not completely captured the impact of dynamic user-oriented

- 32. activity throughout the NPD process (Veryzer & Borja de Mozota, 2005). They do not provide sufficient flexibility to respond to changing information during a development project and therefore are not able to ‘hit a moving target’ in conditions of high-velocity industries (MacCormack, Verganti & Iansiti, 2001). One way to realize flexible NPD is through frequent iterations without forcing early development in a wrong direction or restrain- ing the customers to their initial inputs (Griffin & Hauser, 1993). Multiple explorative devel- opment iterations, complemented by exten- sive testing, and frequent milestones help to overcome the randomness through missing technological and customer information (Eisenhardt & Tabrizi, 1995; Terwiesch & Loch, 2004). Generally, development based on an iterative process further suggests a more real- time, hands-on approach to fast product devel- opment, especially for uncertain products. Lynn, Morone and Paulson (1996) demon- strated that the realization of a process which is able to continually consider new customer input requires probing, testing and learning. This implies a continuous interplay between developers and customers of acquiring, dis- seminating, utilizing, and re-acquiring new customer contributions. Analogies from Successful Practices: Extreme Programming (XP) In the search for analogies to flexible product

- 33. innovation approaches that successfully manage the intersection of customers and R&D, a solution emerges from Extreme Pro- gramming (XP) in the software engineering context. In XP’s product development method- ology, the product innovation process is organized to ensure a continual flow of high- quality contributions from customers to the development activities surrounding a new product. While this approach and the underly- ing agile project management practices have received a high acceptance among software engineers, the concept is less known in the ‘hardware world’ of new product creation. We introduce the Extreme Programming method- ology in the following as it will be used in developing a framework for the investigation of explorative (iterative) practices on integrat- ing customers into the NPD process. Extreme programming is one of the most popular methods of agile software develop- ment which refers to the low-overhead meth- odologies developed for environments with rapidly changing requirements. These meth- odologies minimize risk by ensuring that soft- INTRGRATING CUSTOMERS IN PRODUCT INNOVATION 91 Volume 19 Number 2 2010 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd ware engineers focus on smaller units of work

- 34. (Acebal & Cueva Lovelle, 2002). In agile soft- ware development, collaboration with the cus- tomer throughout the entire NPD process is considered much more important than defin- ing a development contract in advance, and the overall goal is to provide a benefit for the customer as soon as possible (Dornberger & Habegger, 2004). XP is shaped by the incremental, iterative development of sequenced small release (pro- totype) cycles, according to customers’ contri- butions. This procedure minimizes the length of the feedback cycles and helps reveal new customer needs which were not previously known by the customer himself. Empirical research on decision making shows that customers are frequently unaware of their problem situations, underlying preferences, problems and choice criteria (Simonson, 1993; Mullins & Sutherland, 1998). Within the releases, most design activities take place on the fly and incrementally, starting with the ‘simplest solution that could possibly work’ and only then adding complexity. In traditional software development methods, such as the waterfall model for example, first an extensive analysis regarding all product requirements and project time and scope are performed and only after this first stage are the contributions from the customer accessed and released, by translating the requirements into planned product specifications.

- 35. By contrast, XP’s iterative processes have smaller steps and several iterations with working releases in between, where customer contributions are repeatedly accessed, released and absorbed: access refers to developers inter- acting with customers to obtain know-how, release refers to making the customers’ know- how visible to the developer, often in the form of prototypes, and absorption refers to the conversion and internalization of selected cus- tomer contributions into the specific innova- tion project. These terms are equivalent to the acquisition, dissemination and utilization stages in Learning Theory. The customer’s con- tributions are implemented continuously with the customer watching the new product evolve according to his uncovered and released needs and then making further contributions (Dorn- berger & Habegger, 2004). Since in XP the customer receives a physical product element with each release, feedback is provided not from his ability of imagination, but rather the presence of intermediary results enables him to become aware of his unan- swered needs and requirements. As a result, the customer contributes to determining the new product’s scope and functionality at each stage, instead of being contacted only for rel- evance verification and design adjustment, as is the case in traditional software development and in most cases of industrial NPD. While there are many benefits to the XP method, its applicability for NPD is limited to

- 36. certain types of customer needs. That is, XP can be applied only to R&D projects that do not consist of complex technical constructs but instead focus on developments that occur close to the interface with the user of the system. An example from software develop- ment is in the elevator industry where XP is not used to develop the technology for a new elevator concept in which the basic needs still consist of going up and down in a building and opening the doors, but it is successfully applied to develop new functionalities such as floor access control by which the user is directly affected. 3. Reference Framework for the Continual Integration of Customers in Industrial NPD The exploration of XP points out the rel- evance of a differentiated consideration of accessing customer contributions, customer contribution release and customer contribu- tion absorption. This also supports a further consideration of the three elements in organi- zational learning theory where learning about markets for new products can be understood as a process of acquisition, dissemination and utilization of information (see Section 2). Following the structure of customer contri- bution access, release and absorption, we subsequently compare XP’s key elements of integrating customers with the existing cus- tomer integration literature. The presented result is a set of constructs that serve as a ref-

- 37. erence framework which guided our explor- ative investigation of the case studies. Access to Customer Contributions XP succeeds in discovering customer needs and values by collecting customer contribu- tions at the customer’s site and getting a low- functionality version of the product into customers’ hands at the earliest opportunity. Therefore, closeness is crucial in XP, because every finished release gets presented to the customer in the form of a prototype. This pro- cedure may be viewed as a method for rapidly building and disseminating both explicit and implicit market and technology know-how among members of the development team and 92 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT Volume 19 Number 2 2010 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd the customer, which advances the project. Fur- thermore, the customer has a fixed role in the product development team, which also sup- ports the closeness between developers and the customer. In the literature, the closeness factor has been mentioned as a means to build and maintain trust (Anderson & Narus, 1990; Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Buttle, 1996; Hutt & Stafford, 2000; Rindfleisch & Moorman, 2001). Therefore, developers and the customer should interact as closely as possible and in the

- 38. case of ‘sticky’ information possibly even transfer the development project to the cus- tomer site (von Hippel, 1994). The literature on customer integration into product innovation further emphasizes the characteristics of the customer involved, par- ticularly in research on the lead user concept (Herstatt & von Hippel, 1992; Lilien et al., 2002; Morrison, Roberts & Midgley, 2004). Other authors, such as Gruner and Homburg (2000), showed that in addition to lead user characteristics, criteria such as the representa- tiveness of customers for the target market and their reputation in those markets, as well as the intensity of the interaction between the manufacturer and customer beyond a par- ticular project, can significantly discriminate between better or worse performing products. Martin and colleagues (Martin et al., 2003, 2004) emphasize that identifying the indi- vidual within the customer organization with the ability to fulfill the customer role in the XP process represents a success factor. Therefore, the specific person who contributes to the new product under development is an important factor, because he or she determines the role played by the customer. Release of Customer Contributions Research on experimentation modes has high- lighted the role of testing and experimentation during the product innovation process (Simon, 1969; Allen, 1977; Wheelwright & Clark, 1992;

- 39. Iansiti, 1998; Thomke, 1998). Boehm, Gray and Seewaldt (1984) found that a prototyping process, which allows for changes late in the design process according to new know-how from and about customers, resulted in prod- ucts that were not only judged superior from a customer perspective but were also developed with fewer resources. First, XP’s multiple releases (comparable to prototypes) help overcome the customer’s design uncertainty and eliminate potential ex post regrets. Second, the increased number of releases provides the customer with more options from which to choose and thus leads to higher expected design quality, as has been shown by Terwiesch and Loch (2004) in a pro- totyping context. Furthermore, the releases help reduce the customer’s uncertainty about their own preferences and insecurity about the producer’s ability to meet their specific needs. Absorption of Customer Contributions The striking element in XP’s product develop- ment process is the planning activity, which is reduced to a minimum for each release and seems absent in terms of the overall project. In the XP process, the customer contributes to the planning process through regular feedback after every release, which allows more precise estimations of the resources required. These improved estimations reduce the risk that rel- evant functionalities might not be considered. Another customer contribution comes from

- 40. the evaluation of the value of each user story, so that the functionalities may be prioritized according to their relevance. Consequently, explanations of XP’s process can be found in the research field of disci- plined problem solving (Imai, Ikujiro & Takeu- chi, 1985; Quinn, 1985) rather than in a stream pertaining to rational planning (Myers & Marquis, 1969), such as Cooper’s Stage-Gate™ process (Cooper, 1990, 1994, 2001). Delving into the perspective of disciplined problem solving, an explanation for the profitability of XP’s process cycles can be found in the loose– tight concept developed by Wilson (1966) and Albers and Eggers (1991). Within each XP release, in which chaotic trial-and-error devel- opment is allowed, engineers can deploy their full creativity, introduce new ideas, and focus on developments that are technically possible. However, the procedure of collecting cus- tomer feedback occurs with a tight degree of organization. Therefore, developing a new product with XP does not require control over the exact course of a project in either the early or in the late development phases. Instead, only some activities are fixed, and developers can make decisions over the course of their sequence and adoption, depending on the specific situ- ation and variables (Dornberger & Habegger, 2004). Further Elements Relevant for the Reference Framework

- 41. The foundation of XP’s product development process is provided by short, highly efficient development cycles of accessing, releasing and absorbing customer contributions. Cus- tomers assess the intermediary project results continuously and enrich them with their feed- back. This continuous interplay between INTRGRATING CUSTOMERS IN PRODUCT INNOVATION 93 Volume 19 Number 2 2010 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd developers and customers has been addressed in the literature by Lynn, Morone and Paul- son’s (1996) probe-and-learn cycles. They state that repeating the probing and learning helps build new know-how, which leads to a supe- rior new product that has been optimized in terms of technical feasibility and fit with cus- tomer needs. The success of such approaches is seen in the increased likelihood of improved project profitability through continuous guid- ance of the development process by customer requirements and through frequent cost and benefit control which has also been discussed from the perspective of total quality manage- ment (TQM) (Kaulio, 1998). These advantages exceed the costs arising from the provision of multiple prototypes, and the number of devel- opment projects that lead to failures in the market can be reduced significantly (Acebal &

- 42. Cueva Lovelle, 2002). In the following, we use the above dis- cussed constructs as a benchmark, comparing our data of in-house developers and develop- ment contractors against the model using ana- lytic induction (Yin, 1994). 4. Research Methodology Due to the inductive nature of exploring itera- tive customer integration in industrial NPD we chose a qualitative case study approach to gain a thorough understanding of the system (Yin, 1994). We studied several cases in detail to gain an in-depth understanding of their natural setting, complexity and context (cf. Punch, 1998). The research consisted of three phases. In the first phase a literature analysis was con- ducted to explore the existing body of knowl- edge on product innovation processes and customer integration practices. In parallel, the theoretical insights were validated in expert workshops and contracted research projects with industrial goods developers in Northern Europe in order to find inconsistencies and identify further research requirements which are most relevant. This literature analysis and practical reflection led to the theoretical base which was introduced in Section 2. The second phase developed a framework (Section 3) containing the identified aspects in the context of an extreme example of

- 43. experimental NPD, using the XP method from software engineering as a foundation. NPD with the XP method is extreme because innovative customer know-how is extensively utilized throughout the entire NPD process. Because little is known about the XP method in innovation research (the available literature is limited to some practical guidelines), inter- views were conducted with experienced soft- ware engineers. These software engineers work in software departments of the com- panies considered in the first phase or software institutions that specialize in the application of XP (Object XP, Lifeware, FH Zentralschweiz). In the third phase the framework developed with XP was applied to conduct the compari- son between in-house developers and devel- opment contractors. Contractors (professional technical service firms) develop product inno- vations with clients on a project basis – and therefore with a different model of industrial product development than the in-house devel- opers. Both traditional in-house developers and development contractors are included in the research in order to cover a broad spec- trum of industrial NPD settings and thus allow us to investigate the successful applica- tion possibilities of explorative iterative practices. Sample Selection To gain insight we carried out an in-depth

- 44. analysis of selected projects and companies (Stake, 1988; Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 1994). In order to allow for a comparison within the different development models, the investiga- tion took place at the level of specific NPD projects and their practices. We selected four companies in which the product innovation process could be studied comprehensively. The criteria for selecting firms were based on their potential for learning. We selected two in-house developers: Hilti (Liechtenstein) and Buechi Labortechnik (Switzerland) and two development contractors: IDEO (Germany) and Tribecraft (Switzerland). All firms cover the complete spectrum from low- to high-tech. Hilti was chosen due to its reputation as a company that successfully practices a lead- user approach. Buechi excels in its closeness to customers (distributors) and users throughout its product innovation process. As a result of the authors’ close collaborations with this company in previous research projects, we could ensure access to sensitive customer information and a broad data validation process. IDEO – broadly investigated in NPD literature – and Tribecraft engaged in very tight collaborations with their customers and have developed product innovations that stand out in terms of their degree of novelty and superior design. An overview of these four companies is presented in Table 1. Data Collection In all phases, data were collected through per- sonal, face-to-face interviews lasting between

- 45. 94 CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION MANAGEMENT Volume 19 Number 2 2010 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd T ab le 1. O ve rv ie w of In -D ep th C as e S tu

- 53. …