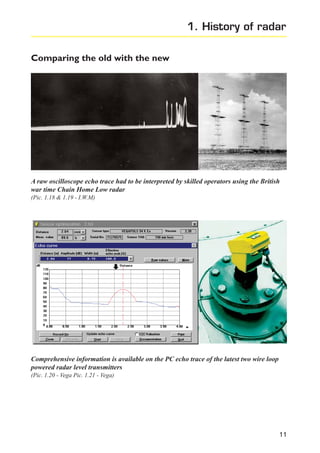

The history of radar began in the late 19th century with Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism and Hertz's experiments verifying the existence of radio waves that could reflect off objects. Early pioneers included Hülsmeyer who invented the first radar system in 1904 and Marconi who recognized its potential for ship detection. During the 1930s, radar was independently developed by several countries including the US, UK, Germany and others. The UK played a key role with Watson-Watt demonstrating radar detection of aircraft at Daventry in 1935. This led to the development of pulse radar and the Chain Home radar network which helped defend Britain in WWII. Germany also made major advances with naval and airborne radar including the Freya,

![2. Physics of radar

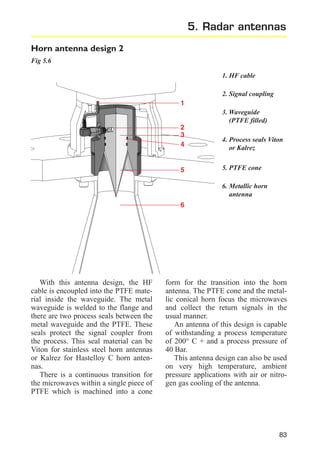

Electromagnetic waves

Th e velocity of light in free space is

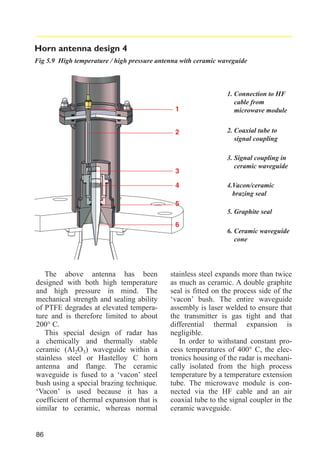

299,792,458 metres per second, but

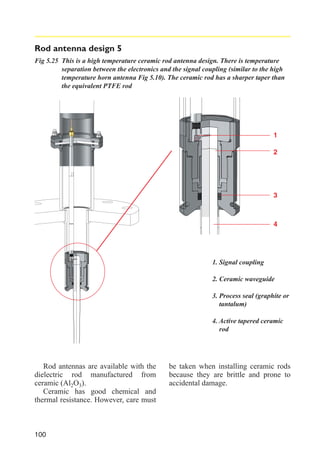

who is timing? For the purposes of the

calculations in this book, we will call it

300,000 kilometres per second or

3 x 108 metres per second.

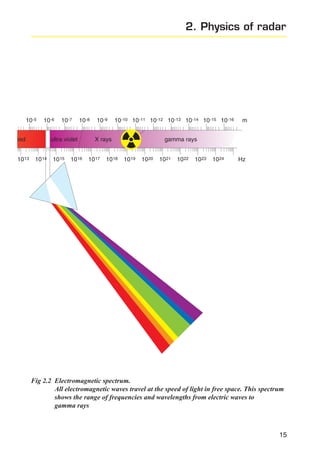

Maxwell’s theories of electromagnetism were confirmed by the

experiments of Heinrich Hertz. These

show that all forms of electromagnetic

radiation travel at the speed of light in

free space. This applies equally to long

wave radio transmissions, microwaves,

infrared, visible and ultraviolet light

plus X-rays and Gamma rays.

Maxwell showed that the velocity of

light in a vacuum in free space is given

by the expression :

Examples :-

1

co =

µo

εo

o

x

εo)

[Eq. 2.1]

velocity of electromagntic wave

in a vacuum in metres / second

the permeability of free space

(4 π x 10 -7 henry / metre)

the permittivity of free space

(8.854 x 10 -12 farad / metre)

c =

f xλ

[Eq. 2.2]

c

velocity of electromagnetic

waves in metres / second

f

λ

frequency of wave in second -1

wavelength in metres

The original cavity magnetron had

a wavelength of 9.87 centimetres.

This corresponds to a frequency of

3037.4 MHz (3.0374 GHz).

The frequency of a pulse radar

level transmitter may be 26 GHz

or 26 x 108 metres per second.

The wavelength is 1.15 centimetres.

The electromagnetic waves have an

electrical vector E and a magnetic vector B that are perpendicular to each

other and perpendicular to the direction

of the wave. This will be discussed and

illustrated further in the section on

polarization. The electrical vector has

the major influence on radar applications.

λ

direction of wave

amplitude

co

(µ

The velocity of an electromagnetic

wave is the product of the frequency

and the wavelength.

Fig 2.1

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-19-320.jpg)

![Permittivity

In electrostatics, the force between

two charges depends upon the magnitude and separation of the charges and

the composition of the medium

between the charges. Permittivity ε is

the property of the medium that effects

the magnitude of the force. The higher

the value of the permittivity, the lower

the force between the charges. The

value of the permittivity of free

space (in a vacuum) εo, is calculated

indirectly and empirically to be:

8.854 x 10-12 farad / metre.

Relative permittivity or

dielectric constant εr

The ratio of the permittivity of a

medium to the permittivity of free

space is a dimensionless property

called ‘relative permittivity’ or ‘dielectric constant’. For example, at 20° C

the relative permittivity of air is close

to that of a vaccum and is only about

1.0005 whereas the relative permittivity of water at 20° C is about 80.

(Dielectric constant is also widely

known as DK.)

The value of the dielectric constant

of the product being measured is very

important in the application of radar to

level measurement. In non-conductive

products, some of the microwave energy will pass through the product and

the rest will be reflected off the surface.

This feature of microwaves can be

used to advantage or, in some circumstances, it can create a measurement

problem.

16

Permeability µ and relative

permeability µr

The magnetic vector, B, of an electromagnetic wave also has an influence

on the velocity of electromagnetic

waves. However, this influence is negligible when considering the velocity in

gases and vapours which are non-magnetic. The relative permeability of the

product being measured has no significant effect on the reflected signal when

compared with the effects of the relative permittivity or dielectric constant.

For the non-magnetic gases above the

product being measured, the value of

the relative permeability, µr = 1.

Frequency, velocity and wavelength

As we have already stated, the frequency (f), velocity (c) and wavelength

(λ) of the electromagnetic waves are

related by the equation c = f x λ.

The frequency remains uninfluenced

by changes in the propagation medium.

However, the velocity and wavelength

can change depending on the electrical

properties of the medium in which they

are travelling. The speed of propagation can be calculated using equation

2.3.

c =

co

(µ x ε )

r

c

co

µr

εr

r

[Eq. 2.3]

velocity of electromagnetic wave

in the medium in metres/second

velocity of electromagnetic

waves in free space

the relative permeability

(µ medium / µo)

the relative permittivity](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-22-320.jpg)

![The same effect can be experienced when looking at interface detection using

guided microwave level transmitters to detect oil and water or solvent and aqueous

based liquids.

Fig 2.4 Oil/water interface

detection using a

guided microwave

level transmitter. Note

that the water echo

has a reduced amplitude and appears to be

further away. The

running time of

microwaves in oil is

slower than in air

reference echo

(water without oil)

oil echo

water echo

Effects on the propagation

speed of microwaves

Microwave radar level transmitters

can be applied almost universally

because, as a measurement technique,

they are virtually unaffected by process

temperature, temperature gradient, vacuum and normal pressure variations,

gas or vapour composition and movement of the propagation medium.

However, changes in these process

conditions do cause slight variations in

the propagation speed because the

dielectric constant of the propagation

medium is altered.

Calculating the propagation

speed of microwaves

The temperature, pressure and the

gas composition of the vapour space all

have an effect on the dielectric constant

of the propagation medium through

which the microwaves must travel.

This in turn affects the propagation

speed or running time of the instrument.

18

The dielectric constant or relative

permittivity can be calculated as

follows :

εr = 1 + (εrN - 1) x θN x P

θ x PN

[Eq. 2.4]

εr

εrN

calculated dielectric constant

(relative permittivity)

dielectric constant of gas/vapour

under normal conditions

(temperature 273 K, pressure 1 bar

absolute)

θN

PN

θ

P

temperature under normal

conditions, 273 Kelvin

pressure under normal

conditions, 1 bar absolute

process temperature in Kelvin

process pressure in bar absolute](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-24-320.jpg)

![2. Physics of radar

W1

Transmitted power:

W2

Reflected power:

Dielectric constant:

εr

Then the percentage of reflected

power at the dielectric layer,

Π = 1-

4 x εr

(1 + ε )

2

r

W2

Π =

[Eq. 2.5]

W1

Typical examples are as follows:

Acetone

Solvent with a dielectric constant,

εr = 20

Toluene

Solvent with a low dielectric consta t

n,

εr = 2.4

Π = 1-

(2.4)

4x

(1 +

Π = 1-

2

(2.4))

4.46% power is reflected

4x

(1 +

( 20 )

(20)

2

)

40 % power is reflected

Π x 100% power reflected

100

80

60

40

20

0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Dielectric constant, εr

Fig 2.7 Reflected radar power depends upon the dielectric constant of the product

being measured

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-29-320.jpg)

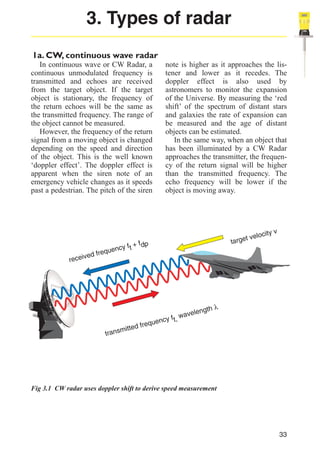

![In Fig 3.1, the aircraft is travelling

towards the CW radar. Therefore the

received frequency is higher than

the transmitted frequency and the sign

of fdp is positive. If the aircraft was

travelling away from the radar at the

v =

λ x fdp

2

=

same speed, the received frequency

would be ft - fdp.

The velocity of the target in the

direction of the radar is calculated by

equation 3.1

c x fdp

c

v

ft

2 x ft

fdp

[Eq. 3.1]

ft+fdp

is the velocity of microwaves

is the target velocity

is the frequency of the

transmitted signal

is the doppler beat frequency

which is proportional to velocity

is received frequency. The sign

of fdp depends upon whether the

target is closing or receding

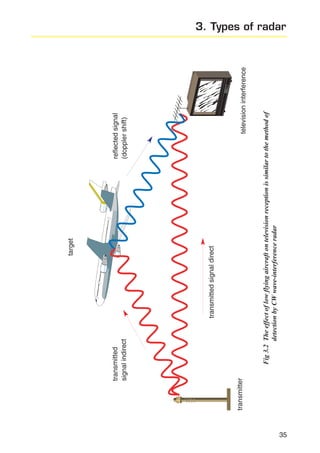

1b. CW wave-interference radar or bistatic CW radar

We have already mentioned that CW

radar was used in early radar detection

experiments such as the famous

Daventry experiment carried out by

Robert Watson - Watt and his colleagues. In this case, the transmitter

and receiver were separated by a considerable distance. A moving object

was detected by the receiver because

there was interference between the fre-

quency received directly from the

transmitter and the doppler shifted frequency reflected off the target object.

Although the presence of the object is

detected, the position and speed cannot

be calculated.

In essence, this is what happens

when a low flying aircraft interferes

with the picture on a television screen.

See Fig 3.2.

1c. Multiple frequency CW radar

Standard continuous wave radar is

used for speed measurement and, as

already explained, the distance to a stationary object can not be calculated.

However, there will be a phase shift

between the transmitted signal and the

return signal.

If the starting position of the object

is known, CW radar could be used to

detect a change in position of up to half

wavelength (λ/2) of the transmitted

wave by measuring the phase shift of

the echo signal. Although further

movement could be detected, the range

34

would be ambiguous. With microwave

frequencies this means that the useful

measuring range would be very limited.

If the phase shifts of two slightly

different CW frequencies are measured

the unambiguous range is equal to the

half wavelength (λ/2) of the difference

frequency. This provides a usable distance measurement device.

However, this technique is limited to

measurement of a single target.

Applications include surveying and

automobile obstacle detection.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-40-320.jpg)

![2.

FM-CW, frequency modulated continuous wave radar

If the distance to the target is R,

and c is the speed of light, then the

time taken for the return journey is:-

2xR

c

∆t =

[Eq. 3.2]

We can see from Fig. 3.3 that if

we know the linear rate of change of

the transmitted signal and measure the

difference between the transmitted and

received frequency fd, then we can

calculate the time ∆t and hence derive

the distance R.

frequency

Single frequency CW radar cannot

be used for distance measurement

because there is no time reference mark

to gauge the delay in the return echo

from the target. A time reference mark

can be achieved by modulating the frequency in a known manner.

If we consider the frequency of the

transmitted signal ramping up in a

linear fashion, the difference between

the transmitting frequency and the

frequency of the returned signal will be

proportional to the distance to the

target.

cy

en

u

eq

r

df

itte

m

ns

tra

re

∆t

fd

c

e

eiv

df

re

e

qu

nc

y

∆t =

2xR

c

time

Fig 3.3 The principle of FM - CW radar

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-42-320.jpg)

![3. Types of radar

3. Pulse radar

a. Basic pulse radar

Pulse radar is and has been used

widely for distance measurement since

the very beginnings of radar technology. The basic form of pulse radar is a

pure time of flight measurement. Short

pulses, typically of millisecond or

nansecond duration, are transmitted

and the transit time to and from the target is measured.

The pulses of a pulse radar are not

discrete monopulses with a single peak

of electromagnetic energy, but are in

fact a short wave packet. The number

of waves and length of the pulse

depends upon the pulse duration and

the carrier frequency that is used.

These regularly repeating pulses

have a relatively long time delay

between them to allow the return echo

to be received before the next pulse is

transmitted.

t

τ

3rd pulse

2nd pulse

1st pulse

Transmitted pulses

Fig 3.9 Basic pulse radar

The inter pulse period (the time

between successive pulses) t is the

inverse of the pulse repetition

frequency fr or PRF. The pulse duration

or pulse width, τ, is a fraction of the

inter pulse period.

The inter pulse period t effectively

defines the maximum range of the

radar.

Example

The pulse repetition frequency

(PRF) is defined as

fr =

1

t

If the pulse period t is 500 microseconds, then the pulse repetition frequency is two thousand pulses per second.

In 500 microseconds, the radar pulses

will travel 150 kilometres. Considering

the return journey of an echo reflected

off a target, this gives a maximum theoretical range of 75 kilometres.

If the time taken for the return

journey is T, and c is the speed of light,

then the distance to the target is

R=

Txc

2

[Eq. 3.3]

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-45-320.jpg)

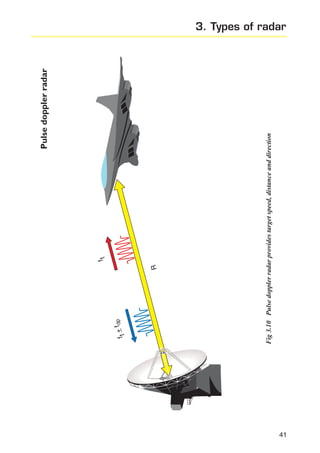

![b. Pulse doppler radar

The pulses transmitted by a standard

pulse radar can be considered as a very

short burst of continuous wave radar.

There is a single frequency with no

modulation on the signal for the duration of the pulse.

If the frequency of the waves of the

transmitted pulse is ft and the target is

moving towards the radar with velocity

v, then, as with the CW radar already

described, the frequency of the return

pulse will be ft + fdp , where fdp is the

doppler beat frequency. Similarly, the

received frequency will be ft - fdp if the

target is moving away from the radar.

Therefore, a pulse doppler radar can

be used to measure speed, distance and

direction.

The ability of the pulse doppler

radar to measure speed allows the system to ignore stationary targets. This is

also commonly called ‘moving target

indication’ or MTI radar.

In general, an MTI radar has accurate range measurement but imprecise

speed measurement, whereas a pulse

doppler radar has accurate speed measurement and imprecise distance measurement.

40

The velocity of the target in the

direction of the radar is calculated in

equation 3.4:

c =

c x fdp

λ x fdp

=

2 x ft

2

[Eq. 3.4]

This is the same calculation as for

CW radar. The distance to the target is

calculated by the transit time of the

pulse, equation 3.3.

R =

Txc

2

[Eq. 3.3]

As well as being used to monitor

civil and military aircraft movements,

pulse doppler radar is used in weather

forecasting. A doppler shift is measured

within storm clouds which can be distinguished from general ground clutter. It is also used to measure the

extreme wind velocities within a tornado or ‘twister’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-46-320.jpg)

![radar_applied_to_level_rb.qxd

15.01.2007

18:46

FM-CW radar bandwidth

The bandwidth of an FM - CW radar is

the difference between the start and

finish frequency of the linear frequency

modulation sweep.

Unlike pulse radar, the amplitude of the

FM - CW signal is constant across the

range of frequencies.

Seite 70

A wider bandwidth produces narrower

difference frequency ranges for each

echo on the frequency spectrum. This

leads to better range resolution in the

same way as with shorter duration pulses with pulse radar.

This is explained in the following diagrams and equations.

frequency

fd =

∆F x 2R

Ts x c

fd

∆F

Ts

R

fd

c

∆F

[Eq. 4.1]

bandwidth

sweep time

distance

difference frequency

speed of light

time

Ts

Fast Fourier Transform

The FAST FOURIER

TRANSFORM produces a

frequency spectrum of all echoes

such as that at fd.

There is an ambiguity ∆fd for each

echo fd.

amplitude

fd

∆fd =

2

Ts

[Eq. 4.2]

∆fd

70

frequency](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-75-320.jpg)

![radar_applied_to_level_rb.qxd

15.01.2007

18:46

Seite 71

4. Radar level measurement

The ambiguity of the distance R,

is ∆ R

∆fd

fd

∆R

R

=

2

Ts

∆F x 2 R

Ts x c

∆R

R

=

c

∆F x R

∆R

R

∆R

=

=

c

∆F

∆R

R

amplitude

distance

Fig 4.24 to 4.26 - FM - CW range resolution

[Eq. 4.3]

From equation 4.3, it can be seen

that with an FM - CW radar the range

resolution ∆R is equal to:-

c

∆F

Therefore, the wider the bandwidth, the

better the range resolution.

Examples:

A linear sweep of 2 GHz has a range

resolution of 150 mm whereas a 1 GHz

bandwidth has a range resolution of

300 mm.

In process radar applications, each

echo on the frequency spectrum is

processed with an envelope curve. The

above equations (Equations 4.1 to 4.3)

show that the Fast Fourier Transforms

(FFTs) in process radar applications do

not produce a single discrete difference

frequency for each echo in the vessel.

Instead they produce a difference frequency range ∆fd for each echo within

an envelope curve. This translates into

range ambiguity.

71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-76-320.jpg)

![5. Radar antennas

A measure of how well the antenna

is directing the microwave energy is

called the ‘antenna gain’.

Antenna gain is a ratio between the

power per unit of solid angle radiated

by the antenna in a specific direction to

the power per unit of solid angle if the

total power was radiated isotropically,

that is to say, equally in all directions.

isotropic power

directional power

Isotropic equivalent with total power

radiating equally in all directions

Directional power from antenna

Fig 5.2 Illustration of antenna gain

Antenna gain ‘G’ can be calculated as follows:

G = ηx

(

πxD

λ

2

)

= ηx

4π x A

λ2

[Eq. 5.1]

Where

The aperture efficiencies of radar

level antennas are typically between

η = 0.6 and η = 0.8.

D = antenna diameter.*

It is clear from equation 5.1 that

the directivity improves in proportion

A = antenna area.*

to the antenna area. At a given freλ = microwave wavelength * quency, a larger antenna has a narrower beam angle

η = aperture efficiency

* must be same units

79](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-84-320.jpg)

![Also, we can see that the antenna

gain and hence directivity is inversely

proportional to the square of the wavelength.

For a given size of antenna the beam

angle will become narrower at higher

frequencies (shorter wavelengths). For

example the beam angle of a 5.8 GHz

radar with a 200 mm (8") horn antenna

is almost equivalent to a 26 GHz radar

with a 50 mm (2") horn antenna. This

Beam angle

φ

=

means that a 26 GHz antenna is lighter

and easier to install for the same beam

angle. However, as discussed in

Chapter 4, this is not the whole story

when choosing the right transmitter for

an application.

For a standard horn antenna the

beam angle φ, that is the angle to the

minus 3 dB position, can be calculated

using equation 5.2.

70° x

λ

D

[Eq. 5.2]

The following graph shows horn antenna diameter versus beam angle for the

most common radar frequencies,

5.8 GHz, 10 GHz and 26 GHz.

Antenna beam angles (diameter / frequency)

beam angle in degrees (-3dB)

80

5.8 GHz

10 GHz

60

26 GHz

40

20

0

50

75

100

125

150

175

200

225

250

antenna diameter, mm

Fig 5.3 Graph showing relation between horn antenna diameter and beam angle for

5.8 GHz, 10Ghz and 26GHz radar

80](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-85-320.jpg)

![Microwave velocity within measuring tube

The speed of microwaves within a

measuring tube is apparently slower

when compared to the velocity in free

space. The degree to which the running

time slows down depends on the diameter of the tube and the wavelength of

the signal.

cwg = co x

{

1-

2

}

λ

( 1.71d )2

[Eq. 5.3]

The microwaves bounce off the

sides of the tube and small currents are

induced in the walls of the tube. For a

circular tube, or waveguide, the

velocity change is calculated by the

following equation :

cwg

co

λ

d

is the speed of microwaves in

the measuring tube / waveguide

is the speed of light in free

space

is the wavelength of the

microwaves

is the diameter of the measuring tube

Fig 5.28 The transit time of microwaves

is slower within a stilling tube.

This effect must be compensated

within the software of the radar

level transmitter

104](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-109-320.jpg)

![5. Radar antennas

There are different modes of propagation of microwaves within a waveguide. However, an important value is

the minimum diameter of pipe that will

allow microwave propagation.

The value of the critical diameter,

dc , depends upon the wavelength λ of

the microwaves: The higher the frequency of the microwaves, the smaller

the minimum diameter of measuring

tube that can be used.

dc =

Equation 5.4 shows the relationship

between critical diameter and wavelength. For example, 5.8 GHz has a

wavelength λ of ~ 52 mm. The minimum theoretical tube diameter is

dc = 31 mm

With a frequency of 26 GHz, a

wavelength of 11.5 mm, the minimum

tube diameter is dc = 6.75 mm. In practice the diameter should be higher. The

diameter for 5.8 GHz should be at least

40 mm.

λ

1.71

[Eq. 5.4]

% speed of light, c

100

80

60

40

20

0

0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2.0 2.2 2.4 2.6 2.8 3.0

Tube diameter / wavelength, d / λ

Fig 5.29 Graph showing the effect of measuring tube diameter on the propagation speed

of microwaves

Higher frequencies such as 26 GHz

will be more focused within larger

diameter stilling tubes. This will minimise false echoes from the stilling tube

wall.

The installation requirements of

radar level transmitters in measuring

tubes are covered in the next chapter.

105](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vega-radarbook-140212093820-phpapp02/85/Vega-radar-book-110-320.jpg)