Saleema Toolkit "English"

- 2. The Saleema Communication Initiative Saleema communication is all about girls and the women they will become. Since the Saleema Initiative started large-scale activities in 2009, the ideal of keeping girls saleema has spread throughout Sudan, and also created interest in neighbouring countries such as Somalia and Egypt. The Saleema model of positive communication is Sudan’s gift to building the best future for girls and women everywhere. The values at the heart of the Saleema Initiative are: • Making the best of the health God gave us, in both body and mind. • Upbringing according to the best values of our culture. • Belief that God created girls and women in the best and safest way to fulfil their future marriage and child-bearing roles. The National Council for Child Welfare (NCCW) started the Saleema Initiative to help partner organisations communicate effectively with families and communities about the importance of keeping their daughters saleema in every way. The Saleema Initiative works through three main types of activities: • Conducting multi-media public awareness campaigns that create widespread recognition of the words, symbols and ideas used to promote the Saleema values. • Reaching families with Saleema communication through relevant institutions that serve the public, for example, maternity hospitals. • Providing organisations working at community level with communication strategies and tools for face-to-face communication based on best practice methods. The ideal of Saleema includes many different aspects of a girl’s physical and social development. The resources contained in this toolkit have a special focus on a fundamental part of a Saleema upbringing: leaving them as God made them, without the harmful changes made by genital cutting. The toolkit is designed to make communicating with families and communities about keeping girls saleema easier, more organised, and more effective. Who is the Saleema Communication Toolkit for? This toolkit is for people who are working with communities to protect girls from all types of genital cutting and would like to use some of the communication approaches, materials and activities developed through the Saleema Initiative. Many of NCCW’s partners in Saleema already have considerable experience of this work, in some cases stretching back through decades. In keeping with the overall Saleema approach, the purpose of the toolkit is to build on the strengths of existing communication programmes, not to replace them entirely. Any group or organisation can use the Saleema tools as part of a programme of communication about female genital cutting. Whether your group is just starting outreach activities or already has considerable community experience, it is useful to think about how the Saleema communication activities you carry out fit into the wider picture of communication about female genital cutting that has been happening in different ways throughout our society for many years. To this end, Part One of this handbook provides background information on important characteristics of communication about female genital cutting in Sudan, specific factors that shaped the Saleema framework, and key features of Saleema communication. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 2

- 3. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 3 What’s in the toolkit? Communication tools help to make communicating easier, more organised and more effective. Sometimes when we talk about communication tools we mean material objects, like posters, printed discussion guidelines, activity guides, a recorded announcement, or a billboard. But concepts and ideas can also be used strategically as tools for communication. For example, the term "saleema" itself is a tool for changing the parameters of discussions about female genital cutting. PART ONE: The Saleema Communication Framework 1.1 Introduction 2.2 Background 3.3 Development of the Saleema Communication Initiative 4.4 Core visual tools 5.5 Benefits of keeping girls saleema 6.6 Saleema communication values 7.7 Saleema messages and message style 8.8 Saleema strategies PART TWO: Tools for face-to-face communication Introduction 9.9 Activity guide 1: Saleema Pledge Commitments (including the Taga) 1001Activity guide 2: How to plan and conduct structured dialogue sessions for Saleema 1111Activity guide 3: Introducing Saleema 1212Activity guide 4: Discovering others' views 1313Activity guide 5: Shared marriage values PART THREE: Additional resources 1414 Sufara’a Saleema 1515Working with religious leaders 1616 Saleema style book: Elements of visual identity

- 4. 4 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE PART ONE

- 5. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 5 PART ONE

- 6. 6 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE “The custom of cutting girls has been with us for a long time in Sudan. All of us alive today grew up with it. No one can say they have not been affected by it. Most of us have experienced it in our own families. Even those whose families kept their daughters saleema can be said to have grown up with cutting through their experience of being different from the majority. The custom goes back before the time of our grandparents and although people tell different stories about it, no one really knows how it started. But everyone knows that our ancestors did not always cut their daughters. There was a time when the mothers and daughters of Sudan were left saleema throughout their lives. The custom of cutting had a beginning, and it has an ending too. We began to see the change some time ago. It comes from improvements in education, especially female education; it comes from the commitment of community organisations that have been persistent in raising the issue for discussion; it comes from the accumulated weight of our collective experience. Now more and more families are joining together in their ideas about what is good for their daughters and for the whole society. The time of Saleema is coming again.” - Nafisa Ahmed Elamin, eminent women’s movement leader

- 7. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 7 PART ONE 1. Introduction The Saleema commitment Making the best of the health God gave us, in both body and mind. Saleema is about making commitments. Small commitments and big commitments that add up to a better society. The commitment of families and whole communities to keeping their daughters saleema has many parts to it. At its heart is a promise to protect and cherish girls as God made them: healthy, whole, unharmed, complete. Therefore the Saleema commitment begins with a pledge to protect girls from physical harm, starting with the life-long harm caused by female genital cutting. This is the foundation of a Saleema upbringing, but Saleema is not just about physical well-being. Girls’ psychological, mental, and social development should also be nurtured and protected so that they can grow up to be women who fulfil all the best potential God has given them, throughout their lives. These different aspects of ‘being saleema’ grow together like two vines and can never be entirely separated. While the Saleema Communication Initiative makes special reference to protecting girls from genital cutting, in broader terms Saleema is as much concerned with healthy minds as with healthy bodies.

- 8. 2. Background Communication about female genital cutting in Sudan Communication about female genital cutting is nothing new in Sudan. Within families and communities it is as old as the practice itself. At the national level, public discourse on female genital cutting goes back at least as far as the 1940s and has accelerated greatly in the past 35 years. While the Saleema Initiative is national in reach the focus is always firmly on communication with and within families and communities. Understanding the spoken discourse on female genital cutting in a particular community -- what kind of conversations are already taking place among the people, who participates in, opts out of, or is excluded from those conversations, and what are the main points of reference -- is essential groundwork for effective engagement. Thus Saleema communication starts not with a call to speak out but with a call to first ask and to listen. Who talks to who about female genital cutting within families and communities? What do they say and how do they say it? Whose voices are privileged and whose are muted or disregarded? Who is silent and why? What ideas or beliefs do people commonly refer to in their talk? What are the areas of disagreement? What is never talked about? What fears are expressed and what wishes? What are people thinking but not saying? What do people think other people are thinking but not saying? What are the common words people use when talking about female genital cutting? These are important questions not only for programme planners but for community members themselves to raise and reflect on. An unwritten rule In most of our communities the cutting of girls has been an unwritten rule for longer than anyone can remember. However it first came about, cutting came to be seen as normal and expected for girls and women. Various reasons are given for it, most of them linked to marriage: cleanliness that is seen as both physical hygiene and moral purity, maintenance of health, religious observance, sexual attractiveness, enhancement of men’s sexual pleasure, curtailment of women’s sexual desire (chastity and sexual fidelity). In a community where cutting is normal, families tend to expect that other families are cutting their daughters, and they feel that they are also expected to cut their own daughters. Historically, girls and women known or believed to be uncut were stigmatized with the insult of ghalfa, gossiped about, and rumoured to be unacceptable as wives; other parents expected that the same would happen to their own daughters if they did not cut them. A related concern that is less frequently mentioned is a fear that unmarried daughters, if not cut, might be so overpowered by natural sexual feelings that they might bring shame on the family through illicit sexual activity. In the academic discipline of sociology this type of unwritten rule about a social behaviour is known as a social norm. Like other societal rules norms change over time. During the time they are most widely in force, however, people often feel that the norm has always been part of the culture and that it will always be there in future. Social norms include rules that are openly broadcast and freely discussed, such as the custom of new mothers staying in the home for 40 days after delivering, as well as rules that are rarely discussed openly but that people learn about by watching how others behave, by ‘listening in', by observing non-verbal communication and by piecing together indirect clues. So norms for a specific type of social behaviour also have norms for how that behaviour should be communicated about. This is important information for anyone designing a programme of communication that aims to engage people in reflecting on and re-evaluating an important social norm. Communicating effectively on a sensitive issue requires good groundwork and careful attention to the community’s established communication norms. The way people talk about an issue often changes and evolves as they reflect on their experiences and respond to new ideas. It is important to understand existing communication norms and dynamics and to engage with people in ways that they are comfortable with. Otherwise you may be seen as deek al’idda (a“cock among the utensils”), charging in and trampling over things with a great clatter, oblivious to the havoc you wreak . Norms for a specific type of social behaviour also have norms for how that behaviour should be communicated about. PART ONE 8 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE

- 9. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 9 PART ONE A Disjointed Conversation Female genital cutting fits the pattern of a norm that is generally not communicated about publicly. Within our families and communities communication about the practice has tended to be fragmented and shrouded by a sense of secrecy and embarrassment. It is common that most of the talk about female genital cutting happens between women. Women talk about the practice with other women for a variety of purposes but often rely mainly on indirect references and tacit understandings. Although successful married life is the main rationale for female genital cutting, many husbands and wives have never discussed the issue directly. Women often say it is required by men as husbands, while men often say it is ‘women’s business’ and that women are the ones insisting on it. Mothers and grandmothers preparing girls to be cut do not provide the girls with realistic descriptions of what is about to happen but rather speak in euphemisms focussed on promised benefits. Girls at the age of first cutting are a muted group in communication on the practice; this is unlikely to change given that the age of cutting in most of our communities is very young. In many cases a wife’s only communication with her husband about her plan to have their daughter cut may be her request for money to pay for it: she is grown now, I need money for the midwife, the henna and the feast. The sense that female genital cutting is not a fit subject for open discussion can make it hard for people to get a clear understanding of the full impact cutting has on their lives. Creating conditions for new kinds of discussions through which new understandings may emerge is a key strategy for Saleema communication. A parallel discourse Growth of public communication on female genital cutting Compared with the muted and circumspect way that families and communities tend to communicate about female genital cutting, Sudan’s public discourse on female genital cutting, as it has developed over the past 35 years, is highly outspoken. ‘Breaking the public silence’ on female genital cutting has been a specific aim and a significant achievement of national- and state-level discourses. In the process new communication norms have been established. Critical discussion of female genital cutting, as the Arabic khitan, has gained acceptance as the frequent subject of public lectures, newspaper articles and opinion pieces, radio and TV programming, theatrical performances, scholarly publications, religious exegesis, public debates, and parliamentary presentations. Three important achievements of this activist-driven discourse have been that: • There is a greater common understanding among people of the health risks. • Important religious experts have clarified that female genital cutting is not required by religion. • Laws have been passed in several states that make it a crime to carry out female genital cutting. Increasing numbers of people have publicly stated their decision to not have their daughters cut. These pioneers have often taken the decision together with their whole extended families. For many people, however, it is not enough just to know the health risks or that female genital cutting is not required by religion or that it might be illegal. They weigh the risks of cutting against the risk of social rejection for their daughters and feel trapped. For many people, the key to change lies in many other people changing too. For many people it is not enough just to know the health risks or that female genital cutting is not required by religion or that it might be illegal. They weigh the risks of cutting against the risk of social rejection for their daughters and feel trapped. For many people, the key to change lies in many other people changing too.

- 10. Rules relevant to Saleema Various types of rules are important in people’s thinking about keeping girls saleema in communities where cutting girls is still seen as a normal practice. Norms Having a sense that cutting girls is a group rule can prevent families from keeping their daughters saleema even when they would prefer to. That the perceived ‘rule of cutting’ is unwritten does not make it any less powerful. What matters is the sense of enforcement: the feeling that the girl herself and the family as a whole will suffer ridicule, embarrassment, and diminished marriage opportunities if the rule is not followed. For those who have not known other saleema girls and women, fear of people’s reactions may be compounded by uneasiness about the unknown: Will she in fact be clean? Will her behaviour be good? Religious rules Although keeping girls saleema is assuredly allowed by religion, some people have understood female genital cutting as a rule relevant to religion. This idea is changing due to clarification by prominent religious authorities that cutting girls is not a religious requirement. Increasing numbers of religious leaders offer this clarification to their followers, with many going further to specifically support keeping girls saleema as more consistent with religion. Several have issued fatwas against cutting girls. See pages 154 -164 for more information on the role of religious leaders in Saleema communication. Legislation Since 2008 five states, South Kordofan, Gedaref, Red Sea, South Darfur and West Darfur, have passed laws banning the practice of cutting girls. Several other states are currently developing similar laws. These include North Kordofan, Northern state, North Darfur and Blue Nile. The development of written laws by state legislatures is a clear and positive sign of how opinion among law-makers has shifted against continuation of female genital cutting; however, the gap between state legislation and community practice is very wide. Enforcement of the new laws is not feasible when cutting, which generally occurs in the privacy of homes and not in public spaces, is still widely viewed as normal and required. To date there is no federal law that prohibits the cutting of girls’ genitals. Since the Saleema Initiative identifies community dialogue and discussion as the starting point for change, these new laws are best viewed as an important parallel development. Having such laws in place is not likely in itself to change the cutting norm. When the norm does shift at community level, however, these laws will become important tools for accelerating change. At the point when pressure for further legal changes and enforcement comes overwhelmingly from communities then legal developments will become part of the Saleema Communication Framework. PART ONE 10 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE

- 11. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 11 PART ONE 3. Development of the Saleema Initiative Against this general background, many partner organisations shared their ideas, research findings, and experiences from the field to help NCCW develop the Saleema Communication Initiative. A number of observations greatly influenced the way Saleema communication strategies and tools were developed. These fall roughly into two groups: signs of positive change, and challenges to change. Understanding these formative influences helps to clarify the aims and methods of Saleema communication. Signs of positive change Most people in Sudan are aware of female genital cutting as a contested practice or an unsettled social question “Are other people thinking about it the way I’m thinking about it?” “I don’t know who to listen to. It’s confusing.” “Is it good or is it bad?” "Which way is this issue going?" “Why are some people in a hurry to change? We must understand this issue better.” “Why are some people dragging their feet? They are holding back the whole society.”

- 12. 12 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE The majority of people share an understanding that the custom of female genital cutting causes health problems for women. "Aspirin, baby powder and medicine for my wife’s women troubles, again..." "I am ashamed of going back to the doctor with these repeated abcesses.". "No, I am sorry, she can’t join us. She is at the clinic again… yes, same old problem…" "It is fistula, she will have to have an operation." "Is this an infection again?" "Why do we do this to ourselves?" People are increasingly aware that female genital cutting is one of the causes of infertility; awareness is already high that cutting makes childbirth more difficult and dangerous for both mothers and babies. "Up to now she has no children, the doctors says there is a problem." "After going through this I will never cut my daughters." “My wife lost so much blood, she nearly died.” "We have lost our daughter, and our grandson too." "It is her third caesarean" "This custom is killing us." "The baby didn’t survive." "We are thinking of trying IVF." “My niece is still in labour, since last night.”

- 13. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 13 PART ONE Many parents experience the decision of whether or not to cut a daughter as a dilemma. "What if we cut her and then by the time she grows up it is no longer required?" "How can we even be sure if it is required now?" "Let us spare her all these problems, we will keep her the way she is." "But if we don’t do it, will it cause her problems in future?" Many people express that they feel trapped by social expectations about cutting girls; they wish there was no pressure to cut their daughters and openly express "I’d leave her the way she is if the others would also leave their daughters as they were created”. "If only we didn’t have to do this." “I’d leave this habit if the others would also leave it.” “I wish they’d keep their daughters the way they are so we could too.” “I wouldn’t do it to my daughters if it wasn’t for my mother.” “I’d change if she’d change.” “Do you think they’d change if we changed first?”

- 14. 14 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE People frequently express uncertainty about the real intentions and actions of others with respect to cutting their daughters. “I heard that they didn’t actually cut their daughters, they only called the midwife to pretend so that the grandmother would be satisfied.” “You mean they don’t want others to “She know?” said that he said that she said they would not cut their girls but I heard it was already done.” In several areas of Sudan, whole communities have joined together in a decision that they will no longer cut girls. We are strong in our decision because we decided together.

- 15. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 15 PART ONE Supporting the trend of positive change Three key Saleema Initiative strategies support and accelerate positive signs of change: From individual to group decision Many of the signs of change noted above highlight the interdependency of people’s decision-making. From the outset, the Saleema Initiative set out to find ways to encourage and support group decision-making. Making change visible It is important for people to know that other people are also thinking about female genital cutting in new ways and that many are taking the decision not to cut their daughters. Making change visible thus became one of the key aims of the Saleema Initiative. Sparking new conversations Although many people express the desire to know what other people are really thinking about the issue, the old patterns of communication about cutting girls mean people often rely on guesswork or make decisions based on inaccurate information. The Saleema Initiative thus set out to encourage new types of conversations about the practice.

- 16. 16 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE Challenges to change As well as numerous signs of positive change in the way that people are thinking about female genital cutting, NCCW’s partners reported a number of challenges consistently encountered in their work at community level. Key challenges • Anxieties about possible negative consequences of leaving girls saleema (sometimes expressed as the loss of perceived benefits of female genital cutting) persist among people who have no direct experience of leaving girls saleema in their families and communities . • Stigma put on uncut girls and women is pervasive and embedded in language, making it difficult to even refer to them in a way that is not prejudicial (the insult of ghalfa). • Debates about different types of cutting (typology) often side-track communication aimed at ending female genital cutting. PART ONE

- 17. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 17 PART ONE While awareness of the problems caused by female genital cutting is generally high, in many quarters cutting girls is also, importantly, seen as a solution to deep-seated anxieties about the female body and about female sexual fidelity (‘benefits of female genital cutting’); these concerns are sometimes expressed in relation to family reputation. "I don’t want to destroy our daughter’s health, but if I don’t cut her will she grow up to destroy our family’s reputation? Maybe she will not be able to control herself." "It is said that when a woman has been cut sexual relations are bad and painful for her, and that is a problem in marriage. It is my plan to marry a woman who has not been cut." "But I have also heard it said that if she is not cut then she will not be sexually satisfied and will go astray." "This custom is causing us too many problems, but if we do not purify our daughters will they be clean? I do not want to leave them in an unclean condition."

- 18. 18 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE The deep-rooted stigmatization of uncut girls and women is a complex and significant barrier to wide-scale change The language commonly used to talk about the custom reinforces stigma against girls and women who have not been cut. There was no generally accepted term for people’s positive choice to protect their daughters from the harm caused by cutting. "Whatever part of Sudan you grew up in, everybody has heard the stories that are told about brides who were rejected when their new husbands found out that they had not been purified." "I didn’t want to have my daughter cut, but in the end I did it because can’t stand the idea that others might look at her as someone who is unclean and lacking morals." "My wife and I decided to protect our girls from all that is bad about cutting, but it is not something we discuss outside the family. As they have grown older we have become more worried about people finding out because of all the gossip people make about girls who are not cut." "We didn’t cut her at first, but she came home crying that she wanted to be purified like the other girls. Her schoolmates were calling her horrible names." "No, no, we didn’t purify her, it’s a very harmful custom. We just, you know… she is just, you know…" "So you just left her like that?"

- 19. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 19 PART ONE Debates about the different types of female genital cutting (typography) exist at every level and undermine efforts to promote abandonment of the practise In addition to issues noted in communities, a review of the ways that communication programmes were working to meet the most significant challenges revealed a need to strengthen some of the commonly used strategies and tools. The shortcomings that were identified in established communication tools and approaches formed an additional set of challenges that needed to be overcome. These are discussed on the next pages in terms of three key shifts in communication strategies and methods. "I suffered so much giving birth, I do not want to bring these problems on to my daughters also." "‘Sunna’ type does not interfere much with childbirth, I think this is the best type for your daughters." "There are some types that are sinful and others that are good in the eyes of God."

- 20. 20 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE SHIFT ONE: From negative to positive The first and most striking communication shortcoming was the prominence of overly negative messaging that was often adversarial in nature. Whereas the custom of cutting girls is embedded in a field of positive values including ideas about social cohesion, beauty, attraction, cleanliness and moral purity, public communication aimed at ending female genital cutting had focussed very strongly on negative events, images, and values: mutilation, pain, suffering, deprivation of rights, violence, death. This powerful negativity served to shock and warn people of the harms associated with cutting girls and women, but failed to provide the majority with a convincing positive alternative to aspire to. The clear message to families and communities was ‘do not cut your daughters,’ but the picture of the alternative was relatively undeveloped. If they were not to be purified, what would they be? Impure? The unspeakable insult of ghalfa? It was clear that more attention should be focussed on the benefits, to girls themselves and to the whole society, of keeping them the way God made them, complete and unharmed.

- 21. What’s wrong with attacking a harmful practice? Good question! Sometimes a powerful negative message can be just what’s needed to open people’s eyes and make them see a problem in new light. But communication tactics that focus too strongly on problems without enough emphasis on exploring acceptable solutions can result in people feeling that they are in a double-bind: a situation of disempowerment in which they have no good options and the best that they can do is to choose the ‘least bad’ option. Given such a choice it is not surprising many people feel more comfortable sticking to what is already familiar to them, even if they are now more aware of risks attached to it. In this situation many people simply tune out the negative messages rather than suffer the stress of repeatedly confronting distressing information about which they feel they can do nothing. Disproportionate attention to some of the most dramatically negative consequences of female genital cutting also leads communicators into the trap of focussing on rare events, for example, the death of a child arising from cutting. The problem with focussing too much on such a rare event is that it does not reflect most people’s experience. After all, most of us know dozens if not hundreds of young girls who have been cut, but only a few people have personally known a girl who died from being cut. The rareness of the event leads people to look for explanations in the circumstances of the cutting rather than the fact of cutting itself. For example, in the case of a child who died because of cutting people may question the skill of the midwife / cutter, the way the family looked after the girl in the home after she was cut, the type of cut that was done. These are all things families can take control over, therefore mitigating the perceived risks without actually needing to discontinue the custom of cutting girls' genitals. Finally, an attack or critique based on a perspective that does not reflect insiders’ understanding of the issue is unlikely to engage people’s hearts. At best it will feel irrelevant; at worst it can make people feel misrepresented, under attack, and defensive. As an example, consider the depiction of midwives. Most families tend to regard the midwife as a helper, an expert in the care of female bodies, a skilled attendant at the arrival of new life, someone the women in the family turn to for a wide range of care services. In negative communication aimed at ending female genital cutting, however, the midwife has often been presented as a villain who seems to revel in the harm she inflicts on innocent girl children. The huge gap between these two perspectives becomes a credibility gap for the communication facilitators. Negative messages should be used carefully and sparingly. Thought should always be given to all the different ways a negative message might affect communication participants, including unintended impacts that could be counter-productive. The issue of timing is important. The child’s death that is dismissed as a freak event by community members who do not feel highly involved in the issue of ending female genital cutting can become a rallying point for change in the same community once opinion has shifted. PART ONE THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 21

- 22. 22 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE SHIFT TWO: From outside expertise to people’s personal experience Whose expertise should take centre stage in communication on female genital cutting? Historically, most organised communication on the issue has derived from national discourses on female genital cutting that, although largely disconnected from family and community level discourses, still serve as the main model for community outreach programming. Development of communication content has relied heavily on sources of expertise from outside the community of people who practise the custom, for example, bio-medical doctors, or human rights experts. This is reflected in the wide use of lecture-based communication activities through which trained facilitators, often dynamic activists for social change, deliver prepared information and perspectives. While the expertise offered in this way is in many instances welcomed by community members, if it fails to resonate with what people know through their own experience the new learning is likely to be compartmentalized and therefore have little impact on future behaviour (we all know people who can describe in detail the harmful effects of cutting girls and then continue to cut their daughters!). As with any other social norms issue, the most effective communication activities are likely to be those that offer people opportunities to reflect in new ways on their own experience and come to a new understanding of it in light of new information. The new insights people gain by sharing their personal experiences and perspectives with each other often have more power to transform their understanding than new information that comes from outside sources. The new insights people gain by sharing their personal experiences and perspectives with each other often have more power to transform their understanding than new information that comes from outside sources.

- 23. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 23 PART ONE SHIFT THREE: From communication products to communication processes Finally, it was noted that communication campaigns on female genital cutting sometimes lacked a clear vision of how communication could bring about change. Many of our early campaigns were based on a widely shared assumption that if people knew the harms caused by female genital cutting they would stop doing it. The information on harm itself, how it was shaped, packaged, and presented, was often the centrepiece of the communication programme. The first problem with this approach is that it wrongly assumes that most of our people are not already aware of significant harms caused by the practice. Secondly, the idea that information about the harmful effects of cutting on its own will spur change does not pay enough attention to perceptions of benefit that persist despite the harmful consequences, or to the powerful social barriers faced by people contemplating change. Indeed, it is abundantly clear that for many if not most people the risks of change – whether viewed as a potential loss of benefits or as rejection by other people -- have often been perceived as greater than the risks of continuing to cut their daughters, even when they are reluctant to do so. Many people plainly state that they are not comfortable putting their daughters in a position that is different from others. Partners working with communities need to work in ways that effectively and naturally link individual change and group change. What is called for at this stage is not the production of a more convincing argument; what is called for is the orchestration of communication processes through which people whose decisions are ultimately interdependent come to understand the issue and each other’s views on it better, and to share more common ground. To do this requires a longer-term framework for communication programmes that take participant’s perspectives seriously and focus on developing better understanding of the community’s own resources for positive change.

- 24. 24 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE The concept of Saleema As a focus on the positive solution, the concept of Saleema provides a powerful platform for responding to these challenges by recalling people to the beauty and goodness of God’s creation and reminding them that girls and women were formed as they were for the purpose of procreation. Because the concept of Saleema is a broad one, relevant to ideas about upbringing and moral character as well as bodily integrity, it also offers a standpoint for engaging with community concerns about appropriate sexual behaviour. In the Saleema framework, good behaviour is the result of good upbringing according to the best values of our culture and cannot be imposed by the cutting of flesh. The idea of damaging something that is in a saleema condition strongly suggests violation and provides solid footing for a human rights perspective that resonates with our communities. The concept of Saleema as a positive value and ideal is deeply embedded in the life of our communities and universally understood; it is not a new idea or something people find difficult to understand. Developing shared meanings of ‘saleema’ in relation to the call to let every girl grow up saleema is a basic step in Saleema communication, one that helps to unify the understanding of participating groups. Finally, the concept of Saleema clarifies that there is no acceptable type of cutting for girls. There is no possibility of making a ‘small cut’ and leaving a girl to be ‘a little bit saleema’; Saleema is an absolute value to be upheld wholeheartedly, without room for doubts or equivocation. Saleema is an absolute value to be upheld whole-heartedly without room for doubts or equivocation

- 25. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 25 PART ONE Saleema communication... 1. Makes change visible 2. Promotes communication processes that raise the voices of ordinary people affected by the practise and encourage new types of conversations 3. Uses and promotes terminologies that reflect the positive benefits of keeping girls uncut 4. Focusses on the strengths of our culture for achieving positive change 5. Promotes group decision-making

- 26. 26 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE 4. Core visual tools The Saleema Colours and the Taga The Saleema Colours A powerful visual can make a statement without the need for any words, like the sight of a crowd of people bedecked in the Saleema Colours. Even someone who has no previous knowledge about the Saleema movement will be struck by the distinctive colours and design, and is bound to speculate that the people wearing them have something in common. These days the bright Saleema Colours, with their swirling design pattern, are widely recognized in many different parts of Sudan as a symbol of the commitment to keeping girls saleema. Wearing or displaying the Saleema Colours is a way of saying that you are part of the Saleema movement. As a tool for making the Saleema commitment visible, the Saleema Colours are always used in print materials and multimedia campaigns. Cloth materials in the Saleema Colours are also sometimes available for use in community Saleema Taga pledge commitment signing celebrations. Part three of this handbook includes a Saleema style book with guidelines on how to use the Saleema Colours and technical guidance for designers to ensure that the colours themselves and the design pattern are always reproduced consistently.

- 27. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 27 PART ONE The Saleema Taga Along with the Saleema Colours, the Taga is another tool for Saleema communication that has a strong visual impact. The Saleema Taga is reserved for a community or group’s firm commitment to keeping their girls saleema. Following a series of community discussion and dialogue activities that culminates in a group decision to keep girls saleema, community members sign their names or make their marks on a full-size Taga to publicize their decision. The signed Taga, with the Saleema Taga pledge written on it, is then displayed publicly to spread the word and invite more people to join the decision. A full size Taga – 10 or more metres of cloth – covered with signatures makes a strong visual impact. The size of it alone communicates scale. A person signing it knows that he or she is joining a large crowd of other people committed to keeping girls saleema. On a different scale, the use of Saleema Pledge Commitments signed (on paper) by smaller groups of people provides a visual reminder of action steps that group members have identified and committed to.

- 28. 28 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE 5. Benefits of keeping girls saleema Safer motherhood – Women’s natural bodies were designed for healthy reproduction and childbirth. Intact muscles and undamaged flesh stretch to meet the demands of childbirth and return to a normal shape after the baby is born. The process of labour and delivery is generally shorter for saleema women. Babies of saleema mothers have a better chance of surviving birth than babies of mothers who have undergone genital cutting. When a mother is not saleema her risk of dying during childbirth is higher due to complications during labour and delivery. A mother’s body cannot function normally when muscles have been damaged by cutting and healthy flesh has become tough and scarred. This leads to long and painful labour that can threaten the life of both the mother and the baby. Saleema mothers have a much lower risk of serious bleeding during childbirth. Cleaner body – Women’s natural genitalia is easy to keep clean. The body has a natural system for cleaning itself during menstruation and at other times. This is damaged by cutting, and normal body secretions can become trapped and remain in unnatural pockets, causing discomfort and other problems. Urination is easily controlled when all muscles are intact, but cutting girls and women often leads to problems controlling urination, including the very serious problem of fistula. Uncontrollable leakage of urine, whether serious as in fistula or minor as experienced at some time by most women who have been cut, causes embarrassment and often restricts women’s physical activity. In severe cases it often leads to social isolation. Healthier body - Women who have not been cut experience fewer infections, fewer wounds, abrasions and abscesses. “When I look at my daughters I feel happy because they are part of a new generation of girls that will not suffer as we mothers have suffered. I am not afraid of the way God made them. They are perfect the way they are.” “How I came to believe in the goodness of keeping girls saleema? It was when my wife delivered our first child. We arrived at the hospital at the same time as another family and I was waiting together with the father of that family. After a few hours a nurse brought the news that his child was born. When his wife was discharged with the baby she came out walking and she was looking strong. Our son was not even born up to then and I asked the nurse why my wife was taking so much longer to deliver. I was afraid that something was wrong. Then the nurse said, the other man’s wife, she is saleema. She is fit for giving birth. But my wife, she is not saleema, that is why the delivery will take long time and my wife was suffering some complications. Finally when my son was born it was a long time after that my wife was allowed to be discharged, and she did not come out walking, she came out being pushed in a wheelchair. That day my eyes were opened. I saw that this was not the way things should be”. “I have got four daughters and the last three are all saleema, although the first one was cut like me myself. My daughters who are saleema have a natural cleanness and purity, they do not suffer so many small infections like those of us who were cut. They are fresh and clean. People sometimes talk about the really serious problems that cutting girls can cause, like when a girl dies, or has fistula, or when a woman dies in childbirth. But most of us don’t complain a lot about the common problems, the ones we live with every day, because it feels too personal. For example, I can’t lift something heavy without leaking a bit of urine every time. It is a small thing, perhaps, but it affects the quality of my life a lot. I am aware that it is a problem for my firstborn daughter too. I am happy that my younger daughters will not suffer the embarrassment and feelings of shame caused by this lack of cleanness.”

- 29. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 29 PART ONE Better fertility – The infections that are more common in women who have had female genital cutting also lead to fertility problems. “I have got two wives, the first one is saleema and the second one is not. They are both women of good character, but the one who is not saleema, she has suffered so many health problems. Normal marriage relations are something painful for her. Even getting pregnant was difficult, even delivering the babies. These things that are meant to be natural. Seeing the difference between my two wives I have no doubt that it is better for all girls and women to be left saleema. Both my wives they are convinced that all our daughters must be kept saleema, it is the right decision.” Feeling of psychological comfort - There is a feeling of comfort that comes from being complete and never having experienced the physical and psychological shock and trauma that every woman who was cut as a child remembers and is affected by throughout her whole life. “My daughters and I share a very close relationship. I know that they have complete trust in me because I have never tricked them or done any harmful thing to them. That’s important to me because like most women my age I remember the shock of losing trust in my parents. It happened when I was so young but I remember it like yesterday: the day that I was cut. The physical pain was terrible, of course, but much worse than that was the total confusion that came from knowing that my parents had allowed this thing to be done to me. As an adult I can understand that parents of their generation thought they were doing the right thing, even if it caused so much suffering. But as a child there was only shock and confusion, the feeling of being betrayed. I was never free with my parents again in the same way after that. Some part of me always remained guarded. When my husband and I agreed with our other relatives to keep all our daughters saleema I felt that a terrible burden had been taken off me. I will never have to do to my daughters what was done to me. I will keep their trust. They will never experience that terrible shock of betrayal by their parents”. Happier marriages – Happier intimate marital sexual relations “I grew up saleema, which was unusual for someone of my generation. I have always been happy to feel whole, complete, but before getting married sometimes I used to worry about what my husband would think. You hear so many things from other women about what men expect. But my husband never complained about our intimate sexual relationship. In fact, he thinks, "she is great”.

- 30. 30 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE Benefits of keeping girls saleema from a medical point of view The questions and answers below highlight several of the benefits of keeping girls saleema. They are excerpted from the booklet Questions and Answers on Saleema from a Religious and Medical Point of View, published by NCCW (2014). The full text of the booklet contains seven additional medical questions articulated by NCCW and the Ministry of Endowment and Guidance and answered by Professor Nasr Abdullah Nasr, member of the Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians. Q. Which is the easier and what is the difference between cleaning and purifying the external genitals of the uncircumcised (saleema) female and circumcised one? A. It is easier to clean and purify the external genitals of the saleema (uncircumcised) female because water easily reaches and cleanses the external genitals, but in case of the circumcised one cleaning and purifying cannot be done thoroughly as some parts are hidden due to jointing and sewing. Q. Does leaving the clitoris intact (without female genital cutting) affect the sexual behaviour of the girl and how? A. The clitoris plays an essential role to feel concupiscence during sexual intercourses. This is a guaranteed right by Islam to the man and the woman so as to enjoy the marital life. The clitoris has this role in the marital life due to the existence of a neural network around clitoris beside a heavy blood circulation at the same position. Q. What is the relation between leaving the external genitals without female genital cutting and the performance of the woman’s monthly cycle? A. When the external genitals are complete then the menstrual blood flows naturally and nothing remains to harm the girl. In the case of female genital cutting, particularly when cutting or joining the labia minor and the labia major, some of menstrual blood accumulates inside the vagina after the end of the days of the blood cycle and such state forms a suitable environment for bacteria growth. This creates conditions for infection for the circumcised girl. In addition there will be secreted material having an unpleasant smell in the next days of the blood cycle. Q. What is the role of the genitals affected by cutting with regard to sexual appetite (concupiscence)? Does female genital cutting minimize, balance or increase the appetite, and how does this happen? A. The genitals most affected by female genital cutting include the clitoris, the labia minor and the labia major. The clitoris plays an essential role in sexual appetite, and when parts of the organ have been cut through female genital cutting it causes a turmoil in the sexual appetite. Such organs are sensitive because they are composed of a quantity of nerves and blood vessels. All should know a fact which is not understood by a lot of people that the feeling of genitals remains to a lesser degree even in the state of the worst female genital cutting because some of these organs that are cut and joined still preserve a part of the nerves and blood vessels. Q. Some people say that delivery is something natural and it can occur without assistance if the woman is saleema. How is that? A. In any delivery there should always be another party to assist the woman in dealing with any complications that could arise, whether the woman is saleema or circumcised. In the case of a woman with female genital cutting, especially if the type includes cutting and joining/sewing of the labia minor and the labia major, without a person beside her for assistance bad consequences will occur immediately and may lead to her death later. The woman may end up being handicapped, or she may develop the medical problem called fistula, or nasoor. But in uncomplicated deliveries (with no special medical risks) a woman who is saleema (without female genital cutting) may deliver without the need for assistance and no harm will happen to her or to her baby. This is because in a saleema woman the vaginal opening has not been subjected to any amendment that caused a tightness obstructing the exit of baby’s head. By contrast, when a woman has been cut the head of the foetus will not be able to pass through the vaginal opening without surgery.

- 31. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 31 PART ONE 6. Saleema communication values Positive Personal Patient Understanding Clear and Simple Spiritual Confident Visible Everywhere Saleema communication is more than the use of special colours and a new way to use words. Saleema communication has a particular style based on commitment to a special set of communication values. Adopting these values changes how we communicate. For facilitators working directly with communities it can require some practice, especially if you enjoy a good argument! Positive Saleema communication is about solutions: first and foremost it is positive. Saleema infuses positive values, ideas and emotions into communication about female genital cutting in ways that both add new direction to the discourse and amplify existing positive trends. The most obvious example of the positive focus of Saleema communication is the promotion of a positive concept and name for uncut girls and women. What’s important about being positive? People receive positive and negative messages in different ways depending on a number of factors. There is no single formula for which type of message is more effective at what step in a change process. However, there is evidence that too much negative messaging turns off people’s interest. This may especially be the case when negative messaging comes at a stage where people do not feel deeply involved with the perspective behind the message. Even where involvement is high, negative messages that cause people worry or alarm without offering them an alternative that feels attainable are more likely to result in despair and resignation than positive action. Whereas negative messaging can result in people ‘disconnecting’ from the communication process, communication tools that use strongly positive concepts and appealing role models invite people to connect through a desire to affiliate. People’s recall of positive messages is generally better than for negative messages. This is particularly the case if those negative messages made them feel bad about themselves or worried that something bad might happen to them. But negative messaging does have a role in communication when it is properly staged. For example, there is some evidence that messages about negative outcomes may have most impact when people are exposed to reminders about them very close to the time they must make a decision. The impact of well-timed negative messaging is of course far more likely when there is a clear positive choice to be made. Saleema is about positive solutions. In the Saleema framework, communication with a negative focus is best restricted to information on the harmful effects of female genital cutting (e.g. health risks, psychosocial injury). Since a wealth of communication materials and activity guides already exist to raise awareness of the harmful effects of cutting girls the Saleema Initiative does not produce anything of that sort. In addition to spreading the use of new positive language and raising awareness of the health and social benefits of keeping girls saleema, Saleema aims to foreground the cultural strengths that make change possible and to make people feel good about their own and their communities’ ability to change for the good. Saleema communication affirms parental love and care. Saleema communication is grounded in the positive recognition that families love their daughters and want to do what’s best for them. A family’s earlier decision to Omar’s Story “My brothers and sisters and I all decided together, back in the 1980s, that when we had children of our own we would never cut the girls. And when I got married Amal also agreed, so all of our daughters, we did not cut them. But at that time it wasn’t something we could speak about. Sometimes neighbours or distant relatives used to ask, ‘this girl is growing, have you… you know?’ And I used to just look down and say, ‘No, no, we don’t agree with that thing, we didn’t do it to her.’ That was all we could say in those days. But now if someone asks about our youngest daughter I can look at them and say ‘We kept all our daughters as saleema.’ And when I say that I feel happy - I feel great.”

- 32. 32 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE cut a girl would have had the same motivation as the decision they take now to keep her saleema: their sense of what is best for her now and in future. Saleema communication affirms the importance of social unity. Our people have a lot of cultural capital when it comes to social unity. The feeling of belonging, of being a member of a harmonious group, is valued for itself, not only to avoid conflict or social sanction. The custom of female genital cutting, now often seen as a source of division within families and communities, itself was once viewed as a unifying force for community identity. The same factors that supported keeping cutting as a norm, such as people’s reluctance to stand apart from the group or to disturb the balance of the group, also support the shift to keeping girls saleema. Saleema communication promotes inclusive dialogue in which the perspectives of all community members are listened to respectfully and with positive regard. Saleema communicates a positive message visually as well as in words, using beautiful colours and attractive images, holding up a positive mirror on the culture. Personal Saleema communication materials speak in the voices of ordinary people, telling their personal stories. It is part of the shift away from outside expertise to focus on ordinary people’s own personal experiences and perspectives. Mothers and fathers who have taken the decision to keep their daughters saleema and all the different paths that led them there; sisters who have experienced being different from each other; grandparents who have seen and celebrated the change in their community; new parents making the Born Saleema pledge for their first child, a tiny baby girl. The expertise these ordinary people have gained through their own experiences offers valuable models to others contemplating change. ‘Keeping it personal’ in Saleema communication means speaking in your own voice, about your own personal experiences. Thus when a doctor tells her story she speaks as a mother or as a daughter or as a grandmother or a sister or as all of these roles, not as a medical expert with no apparent personal involvement in the issue. When a famous singer or leader speaks as an ambassador for Saleema he speaks about his own life experience and of the process of decision-making in his own family. Saleema mass media materials are also designed to echo and reflect common dilemmas and the solutions embraced by everyday people. All the stories used in Saleema radio and TV spots as well as the quotations that appear as messages on Saleema posters and other print materials are drawn from interviews and discussions with ordinary people talking about their own lives. Amira’s story “As a doctor I know that every part of the human body was designed for a purpose, none more so than a woman’s reproductive parts. As a woman myself I have lived with many problems due to being cut, especially when giving birth. My husband is a doctor too and he was the first one to say that we must leave our daughters saleema. Still, there were times when it wasn’t easy for us to feel strong in our decision. My mother didn’t understand and she put a lot of pressure on me. I thought about lying to her but she is very tough – she could even inspect the girls herself. So I had to tell her the truth and put up with a lot of arguments and complaints. I have always tried to be a good daughter and it hurt me to feel that I was disappointing her. For several years there were problems in the family because of this disagreement, especially when my younger sister also decided to leave her daughters saleema and my mother blamed me. I was even afraid to leave my girls with their grandmother at school holidays. To tell you the truth, there was a time when I almost decided to cut them just to improve relations with my mother. But then my husband said ‘You have a duty to your mother and a duty to our daughters, too.’ He said cutting the girls was not the solution. It was my father who helped the situation. Before this he always used to say issues like this were ‘women’s business’ and he refused to get involved. But because of the problem between me and my mother he opened a discussion with his brothers and all their sons, and this led to a family meeting. My mother was surprised to hear almost everyone saying that they wanted to leave their daughters saleema, especially the most respected women. That was years ago. My daughters are grown and the eldest is married now. My mother is very old but she still has an active mind. Recently there was a famous singer talking on the radio about the Saleema movement and I was happy when I heard my mother telling my youngest daughter ‘Why do they make a big fuss? It is nothing new. We decided a long time ago'.

- 33. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 33 PART ONE Patient The Saleema Communication Initiative is designed as a long-running undertaking. Change takes time. The slow time of perceptions shifting, of group and individual processes of reflection and re-evaluation, of negotiation within individual relationships and within larger social groups, of set-backs and leaps forward. It is not a case of simply presenting a winning argument. Change takes time to organise. It takes time to reach effective scale. Exposing people to the same simple incontestable message repeated over long periods of time is often more effective in re-orientating their perspective than one very persuasively constructed comprehensive argument. Progress is not linear, it is sometimes circular, doubling back, regressing, surging ahead again. Some ideas have the most impact when they’ve been around so long they seem obvious to everyone. Other ideas jolt people into immediate action. Repetition over a long time frame can signal stagnation or strategic choice. Although substantial change, when it comes, may appear to be very rapid the groundwork for it has very often taken a long time to lay. Understanding Saleema communication starts from a position of empathy with families for the difficult choices they have faced in relation to the custom of female genital cutting. This is reflected in Saleema communication materials through a commitment to exploring challenges and barriers to change, and raising the voices of people who have succeeded in overcoming them. Saleema is always with the community, not against it, and respectful of its sensitivities. Clear and simple When it comes to discussion of female genital cutting, Saleema is clear and simple: it means no damage, no cutting of any type. Perfect, as created by God. Saleema is an absolute value: you cannot keep your daughter ‘a little bit saleema’. To debates about ‘sunna’ compared with ‘pharonic’ and so on there is one clear and simple answer to make: we want our girls to be saleema. Nothing further needs to be said. Spiritual Saleema asserts respect for God’s creation: it’s a core value of the society and at the very heart of the Saleema Initiative. Saleema engages the participation of like-minded religious leaders and finds new ways to amplify and spread their teachings that female genital cutting is not required by any religion. “I used to spend so much time arguing with people who promoted the idea that female genital cutting is good. There are always one or two people in any audience who are there just to start a debate and they will argue constantly and spoil the whole meeting. The worst was when they started talking about ‘sunna’ cut and saying it is good, it is only 'pharonic' that is bad. Then the whole group would break out discussing and arguing about different types of cutting and the meeting would end that way. Now when that happens I just let them have their say, and then I give my answer: we want our girls to be saleema. That answer changes everything. I no longer waste my energy arguing with people who are not ready to join the change.” - NGO worker

- 34. 34 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE Confident If Saleema was a lady she would have an air of quiet confidence about her: she is sure of herself and her beliefs. She takes time to explain but she does not stoop to argue. She avoids the pitfall of debates, knowing that they can only end with winners and losers, dividing people instead of bringing them together. She is tolerant of those who speak against her but she does not waste her energy trying to convince them. They will change in their own time, and there are so many others who are interested in engaging in new thinking now. Her tone of confidence and her steady optimism gives them courage.

- 35. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 35 PART ONE Visible The Saleema change is already happening all around us. More people, individually and as members of communities, develop confidence to join the change as it becomes more visible in the society around them. Making change visible is one of the most important Saleema Initiative strategies and a key aim of Saleema’s main communication tools: the Saleema Colours and the Saleema Taga. Wearing or displaying the Saleema Colours allows individuals and whole communities to communicate their commitment in a way that is bold, colourful, fun and also suitably discreet. Anyone who supports the shift to keeping girls saleema is entitled to wear the colours; it is not a direct reference to the condition of any specific girl’s or woman’s body. It is a statement of commitment to a Saleema future for their own family and the larger society. By signing their names on the Taga people put their commitment on record for others to see. The thousands upon thousands of names filling the length of a Taga demonstrate to others who are still considering the change that they and their families will be part of a very large movement of people. Everywhere The concept of bringing up our girls and honouring our women as Saleemat is a big idea, a big house, a far-reaching social transformation. It is an ideal already embedded deep in our culture that we now challenge ourselves to attain, not as individuals acting alone but in family groups and whole communities. To support this improvement effectively we need to work at a big scale. No one should be left out. Every group engaged at community level, every activity conducted, should be seen in relation to the larger society. Certain foundational goals are best achieved through working at the largest possible scale, like making strategic use of mass media as a powerful tool for spreading and promoting the use of new terminologies.

- 36. 36 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE 7. Saleema messages and message style What should we expect from a message? The idea that organised communication is about sending and receiving messages is a basic one that is often over-simplified. In the Sender-Message-Receiver model of communication, the facilitator of an organised communication activity is usually identified as the 'sender' while the community members are seen as 'receivers.' Simple, right? Well, it would be simple if this was the only time and place communication on this issue had ever happened or will ever happen for these people, if this message was the only ‘message’ on the issue, if this facilitator was the only ‘sender’ and these were the only ‘receivers,’ if the subject of the communication was something with no connection to the receivers personal lives. This is definitely not the case when we communicate about issues related to female genital cutting. A community participant receives any message a speaker sends through organised communication about the issue of cutting girls through the filter of a much wider field: of values held, of a lifetime of things said and heard, implied or tacitly understood, about female genital cutting. This larger and long-lasting communication includes all the things a receiver has ever heard and said and observed and surmised in relation to cutting, within their families and close personal relationships, in the larger community, and through channels such as mass media, both in the past and on a continuing basis. In Sudan today it is a dynamic, wide-ranging, field of messages made up of many different voices and perspectives. It includes ideas and voices that support and reinforce each other as well as those that conflict with and contradict each other. Any message ‘sent’ through one particular material or activity becomes part of this broader field of ideas and is interpreted by receivers according to how it fits with their established knowledge, opinions and experiences. An effective message succeeds in engaging the receiver’s broader field of ideas, affirming a preference or prejudice, throwing a belief into new light, casting a shadow of doubt on a received idea, sparking a new insight. An ineffective message is quickly disregarded. All messages are not equal: messages sent by some senders automatically have more power than others based on the sender’s relationship to the receiver. A message that confirms a receiver’s existing belief tends to have more power than one that conflicts with it. A simple message repeated over time is likely to have more impact than a complex message delivered on one occasion.

- 37. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 37 PART ONE The Saleema Initiative has a message style that is simple, distinctive, and personal. In visual materials message texts and images are designed to intrigue, to catch attention and to resonate on a deep level with the personal experience of community members. Saleema communication sticks to a few key messages and makes extensive use of indirect and non-directive messaging. It has been said that Saleema messages are not aimed like arrows straight at targets but rather wafted like perfumes that catch people’s attention unawares. Repetition of key Saleema values and ideas staged over a long time frame is an important strategy. An element of mystery is sometimes deliberately included through the use of intriguing hooks that pique people’s curiosity and draw them into a process of interpretation. Since most people are more accustomed to direct, unambiguous messages, it is not uncommon to hear people reacting with some confusion at their first exposure to Saleema communication messages: What is this about? What is the message here? What is the rationale for such a message style? Why not just tell people, and tell them only once, what you want them to do? These questions are not infrequently raised, especially in relation to the aim of ending female genital cutting. Here it is useful to recall that decades of exposure to messages telling people not to cut their daughters had little impact on family practice. The point is not to tell people what to do; the point is to engage people in reflection and new ways of thinking that allow them to reach new understandings of their own experience (as individuals, as members of families and communities) in relation to the ideal of Saleema. Saleema’s indirect messages invite people to construct relevant meanings based on their own life experiences; the focus is on the step-by-step actions that draw people into processes of reflection and values clarification aimed at generating a new consensus. On the most immediate level, all Saleema materials ask audiences to make connections: between words and images, between colours and patterns, between words and pictures and emotions, between the contents of a poster or sticker or radio spot and their own personal life experiences. Rather than a list of key messages, it is useful to think of Saleema communication as creating a message field. In style, Saleema messages echo and reflect perspectives and experiences that are common in our communities. Most Saleema messages have one of two general types of content. The first are the Saleema basic messages that reinforce the idea that keeping girls saleema is a positive decision made by increasing numbers of families. A second general group of messages are those that draw on real-life stories to explore specific challenges and the responding strengths of individuals and communities that have joined the Saleema movement. Examples of the second type of messages can be found in the ‘Saleema Because…’ series. Saleema field of basic messages Expressed as simple statements, the Saleema field of basic messages would include the following ideas: • (the condition of being) saleema is good. • (the condition of being) saleema is beautiful. • (the condition of being) saleema is clean and pure. • (the condition of being) saleema is healthy. • (the condition of being) saleema is a marriageable condition • (the condition of being) saleema is God’s intention. • (the condition of being) saleema is a cause of happiness and joy. • (the concept of) saleema is integral to our culture.

- 38. 38 THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE PART ONE • The idea of keeping girls saleema is growing / spreading. • These colours / symbols mean the subject is related to keeping girls saleema. • (In communication about Saleema) the voices, experiences and perspectives of ordinary people are important. • (Communication about) Saleema is about making the right decision for girls and women. • (Communication about) Saleema is about making a commitment together with others. • (Communication about) Saleema is about social harmony, unity, family and cultural identity. • (Communication about) Saleema is everywhere. • (Communication about) Saleema is about moral fibre and the importance of character (both in terms of social upbringing and having the courage to change / make the right decision). • (Communication about) Saleema is about what is best in our culture(s) Saleema communication does not include reference to female genital cutting in its main field of messages, a fact that has perplexed some observers. On the most basic level the reason for this is that Saleema communication is not about cutting. Saleema is ultimately not even about not cutting. Saleema is about the perfect way God made girls and women. It is what belongs in the gap felt in public discourses about female genital cutting: an appealing and safe alternative to cutting girls. To attempt to develop and build up the idea of Saleema with constant reference to cutting would be to tie it to a different and conflicting message field and weight it with old baggage. This is not to say that communication tools that focus on the harm caused by female genital cutting should not use the Saleema terminology – not at all. But the whole Saleema package, the branding so to speak, should not be mixed helter-skelter with communication components that are harm-focussed. As people begin to understand that Saleema communication is about what is best in our culture, the early expectation that Saleema should send direct messages about the harm caused by female genital cutting begins to fall away. In place of the old assumptions comes an understanding that the style of Saleema is to invite self-reflection, asking people to measure their own personal and community outlooks and actions with a Saleema yardstick and trusting them to make important connections on their own. Such important connections crucially include, but are not limited to, the custom of female genital cutting. The opportunity to explore different aspects of what it could mean to keep a girl saleema and to come up with personal or group interpretations is an important part of Saleema communication. There is no definitive set of Saleema characteristics – different groups emphasize different aspects. Pre-testing of Saleema Initiative tools has repeatedly confirmed that the great majority of community communication participants make a connection with female genital cutting on their own. Sometimes the connection is made immediately. At other times the connection is expressed tentatively at first but rapidly grows in certainty as discussion develops within a group. This linkage is all the more powerful for people having made it on their own, and often leads to communication participants ‘owning’ and sharing with other participants information and experiences relevant to the risks of female genital cutting. Informal peer-to-peer communication of this type, observed repeatedly in the process of pre-testing Saleema communication tools, is a thousand times more powerful than any direct message we could send. A common example is when members of a group of women participants begin talking about their own personal experiences of health problems arising from having been cut, leading others who have had the same problem to realize that their problem is common among their peers - they are not alone. A direct message stating that female genital cutting commonly causes health problems does not have the same personal impact. Why doesn’t Saleema communication talk about cutting girls? On the most basic level the reason is that Saleema communication is not about cutting. Saleema is ultimately not even about not cutting. Saleema is about the perfect way God made girls and women.

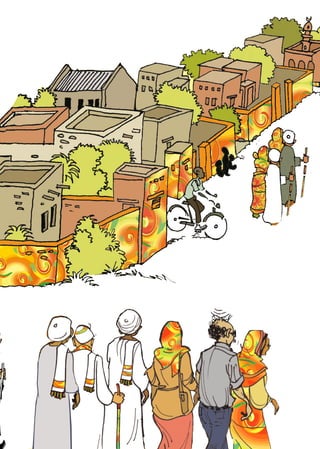

- 39. THE SALEEMA COMMUNICATION INITIATIVE 39 PART ONE The Saleema style book section of this toolkit contains important guidance on when and how to use Saleema messages and symbols in relation to communication programmes that contain a significant focus on the harm caused by female genital cutting. The Saleema strapline, or ground message, used throughout Saleema communication is, with its clear call to action, the most direct and explicit Saleema message: Every girl is born saleema, let every girl grow up saleema But what does it mean to let a girl grow up saleema? The audience is invited to actively engage with the question. The aim is not to deliver a prescriptive message but to stimulate people to make interpretations that resonate with their experience, to arrive at new understandings of their own lives. This Saleema poster from 2010 contains the ground message and also sends a lot of supporting messages through the visuals. In an indirect but very clear way, it creates connections between the presence of families and especially of girls and women, the word 'saleema', the colours and pattern of the Saleema design, and the idea of beauty. A sense that something of importance to the whole society is happening is conveyed by the diverse crowd of people moving in the background. Their unity of purpose (everyone is moving in the same direction) and the positive mood conveyed suggest social harmony. The figures in silhouette provide visual interest, throwing the contrasting Saleema Colours into sharp relief; they also add an element of mystery that intrigues people and causes them to ask ‘What is this all about? What is the difference between the colourful figures and the silhouettes? What is the message here?’ The main message text, which is drawn from a real-life interview with a mother who has committed to keeping her younger daughters saleema, alerts people to the fact that Saleema communication is associated with a choice or decision: ‘Saleema…because I am strong in my decision’. How do we know that the poster does all of these things? Like all other Saleema Initiative communication tools it was carefully pre-tested at community level in different parts of the country before mass production. Saleema pre-tests are designed to explore all the associations people make with the words and images, how involved they feel in the scenes and ideas represented, and the interpretations they make of them. Have a look at the Saleema field of basic messages listed on pp 37-38. How many of those messages is this poster sending?