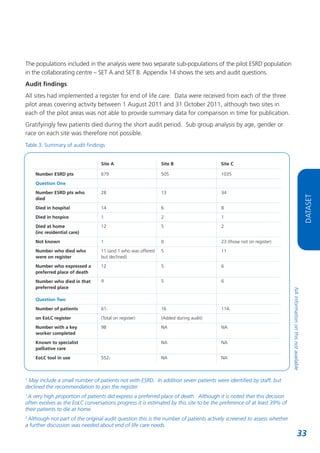

This document outlines a framework for end-of-life care in patients with advanced kidney disease, highlighting the need for systematic identification, planning, and coordination of care. It synthesizes experiences from project groups in Bristol, Greater Manchester, and London, focusing on improving palliative care delivery through training, communication, and support for patients and their families. Recommendations include the establishment of patient registers, advance care planning, and better collaboration across healthcare services to ensure dignified care at the end of life.

![References

1

Department of Health. National Service Framework for Renal Services – Part Two: Chronic kidney

disease acute renal failure and end of life care. 2005 [viewed 2012 Feb 13] Available from:

http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4102680.pdf

2

Department of Health. Our Health, Our Care, Our Say: a new direction for community services.

2008 [viewed 2012 Jan 24] Available from:

http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4127453

3

Department of Health. High Quality Care for All Our NHS Our future: NHS next stage review final

report. 2008 [viewed 2012 Jan 24] Available from:

http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_085828.pdf

4

Department of Health. End of Life Care Strategy. 2008 [viewed 2012 Jan 24] Available from:

http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_086345.pdf

5

NHS Kidney Care. End of Life Care in Advanced Kidney Disease: A Framework for Implementation.

2009 [viewed 2012 Feb 13]. Available from: http://www.kidneycare.nhs.uk/Library/endoflifecarefinal.pdf

6

Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Shaema S, Gansor J, Senft S, Weaner B, Dalton C, MacKay K, Pellegrino B,

Anantharaman P, Schmidt R. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High

Mortality. Clinical Journal of American Society of Nephrology 2008; 3(5):13791384

7

Cohen LM, Ruthazer R, Moss AH, Germain MJ. Predicting SixMonth Mortality for Patients Who Are

on Maintenance Haemodialysis. Clinical Journal of American Society of Nephrology. 2010; 5(1):7279

8

The Edmonton Symptom assessment system. [Internet] 2012 [viewed 2012 Feb 13]. Available from:

http://www.palliative.org/PC/ClinicalInfo/AssessmentTools/AssessmentToolsIDX.html

9

Richardson LA, Jones GW. A review of the reliability and validity of the Edmonton Symptom

Assessment System. Current Oncology. 2009; 16(1): 55.

10

POS S Palliative care Outcome Scale – Symptoms. [Internet] 2012 [viewed 2012 Feb 13].

Available from: http://www.csi.kcl.ac.uk/poss.html

11

Information about the Gold Standards Framework. [Internet] 2012 [viewed 2012 Feb 13]. Available

from: www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk

12

EQ5D. [Internet] 2012 [viewed 2012 Feb 13]. Available from: http://www.euroqol.org/home.html

13

National End of Life Care Programme. Planning for Your Future Care. Revised 2012 [viewed 2012

Feb 13]. Available from: http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/publications/planningforyourfuturecare

14

National End of Life Care Programme: Preferred Priorities for Care. Revised 2007 [viewed 2012 Feb

13]. Available from: http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/tools/coretools/preferredprioritiesforcare

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gettingitrightweb-131111070215-phpapp01/85/Getting-it-right-end-of-life-care-in-advanced-kidney-disease-38-320.jpg)

![15

National End of Life care programme: Holistic common assessment of supportive and palliative

care needs for adults requiring end of life care. March 2010 [viewed 2012 Feb 21]. Available from:

http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/publications/holisticcommonassessment

16

NHS Kidney Care. Caring for Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease at the End of Life – Ten Top

Tips. 2011 [viewed 2012 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.kidneycare.nhs.uk/Library/EoLCTenTopTips.pdf

17

Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient (LCP). [Internet] 2012 [viewed 2012 Feb 13].

Available from: http://www.mcpcil.org.uk/liverpoolcarepathway/index.htm

18

Stewart MA. Effective physicianpatient communication and health outcomes: a review. Canadian

Medical Association Journal. 1995; 152(9):142333

19

Wilkinson S, Roberts A, Aldridge J. Nursepatient communication in palliative care: an evaluation

of a communication skills programme. Palliative Medicine.1998; 12(1):1322

20

Wilkinson S, Bailey K, Aldridge J, Roberts A. A longitudinal evaluation of a communication skills

programme. Palliative Medicine. 1999; 13(4):3418

21

Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Can communication skills training alter physicians’beliefs and behavior in

clinics? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002; 20(3):7659

22

Clayton JM, Hancock KM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Currow DC, Adler J, et al. Clinical practice

guidelines for communicating prognosis and endoflife issues with adults in the advanced stages of

a lifelimiting illness, and their caregivers. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007 Jun 18; 186(12

Suppl):S77, S9, S83108.

23

End of Life Care in Advanced Kidney Disease: A Framework for Implementation – interactive

session within the ‘Integrating Learning’ module. [Internet] 2012 [viewed 2012 Jan 24]. Available

from: http://www.elfh.org.uk/projects/eelca/index.html

24

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Quality standard for end of life care for adults.

2011 [viewed 2012 Feb 13]. Available from:

http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qualitystandards/endoflifecare/home.jsp?domedia=1&mid=E9C7F83619B9E0B5D4B49B5A7

149F081

25

National End of Life Care Programme. End of Life Locality Register Evaluation. Final Report June

2011 [viewed 2012 Feb 13]. Available from:

http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/publications/localitiesregistersreport

REFERENCES

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gettingitrightweb-131111070215-phpapp01/85/Getting-it-right-end-of-life-care-in-advanced-kidney-disease-39-320.jpg)