Missouri R.Mississippi R.Ohio

- 1. M isso uri R . Mississip p i R . Oh io R. Gulf of Mexico M isso uri R . Mississip p i R .

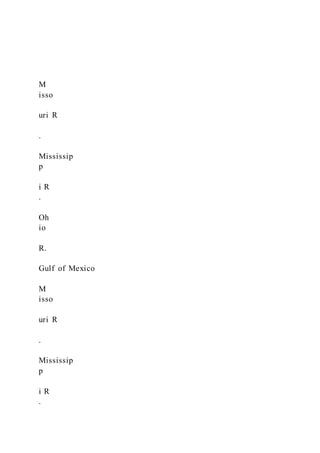

- 2. Oh io R. 0 250 500 KILOMETERS0 250 500 MILES0 250 500 KILOMETERS0 250 500 MILES ▲Figure GN 14.1 Map of the Mississippi River basin. 409 GEOSYSTEMSnow The Disappearing Delta Before modern engineering of the chan- nel, the Mississippi River carried over 400 million metric tons of sedi- ment annually to its mouth. River deposits built from this sediment now underlie most of coastal Louisiana. Today, the flow carries less than half its previous sediment load. This decline, combined with land subsidence and sea-level rise, means that the delta region is shrinking in size each year. The tremendous weight of sediment deposition at the Missi ssip- pi’s mouth has caused the entire delta region to lower as

- 3. sediments become compacted, a process that is worsened by human activities such as oil and gas extraction. In the past, additions of sediment bal- anced this subsidence, allowing the delta to build. With the onset of human activities such as upstream dam construction, the delta is now subsiding without sediment replenishment. Compounding the problem is the maze of excavated canals through the delta for shipping and oil and gas exploration. As the land surface sinks, these canals allow seawater to flow inland, changing the salinity of inland waters. Freshwater wetlands whose roots help stabilize the land surface during floods are now declining. This makes the delta more vulnerable to flooding from hurricane storm surge, another factor hastening the delta’s demise. Finally, sea-level rise threatens coastal land and wetlands, most of which are less than 1 m (3.2 ft) above sea level. With continued local sea-level rise, lands not protected by levee embankments and other structures that prevent flooding will con- tinue to submerge. In this chapter, we examine the natural pro- cesses by which rivers erode, transport, and de- posit sediment, forming landforms such as deltas. 1. Why are engineers trying to keep the

- 4. Mississippi River in its present channel? 2. What three factors are causing the Mississippi delta to disappear? Changes on the Mississippi River Delta T he immense Mississippi River basin drains 41% of the continental United States (Figure GN 14.1). From its head- waters in Lake Itasca, Minnesota, the Missis- sippi’s main stem flows southward, collecting water and sediment over hundreds of miles. As the river nears the Gulf of Mexico, the flow energy diminishes and the river depos- its its sediment load. This area of deposition forms the delta, the low-lying plain at the river’s end. Like most rivers, the Mississippi continu- ously changes its channel, seeking the short- est and most efficient course to the ocean. In southern Louisiana, the Mississippi’s chan- nel has—over thousands of years—shifted course across an area encompassing thou- sands of square miles. Throughout this time span, floods caused the river to abandon pre- vious channels and carve new ones. The Mis- sissippi River attained its present position about 500 years ago and began building the delta we see today (Figure GN 14.2). Engineering the River Channel Since about 1950, engineers

- 5. have worked to keep the Mississippi River in its present channel, a feat accomplished by dams, floodgates, and artificial levees (earthen embankments designed to prevent channel overflow). The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the Old River Control Structure in 1963 to block the Mississippi River from shifting westward toward the Atchafalaya River, which takes a steeper, shorter route to the Gulf of Mexico. Such a shift would cause the river to bypass two major U.S. ports, Baton Rouge and New Orleans, with negative eco- nomic consequences. Despite such measures, the Atchafalaya delta is growing even as the rest of the Mississippi’s delta disappears. 0 15 30 KILOMETERS0 15 30 MILES Mississippi River delta Old River Control Structure Atchafalaya River delta Atchafalaya

- 6. River Gulf of Mexico M is s is s ip p i R i v e r ▲Figure GN 14.2 Mississippi River landscape, southern Louisiana. Inset photo shows the Old River Control Auxilliary Structure. NASA/USGS; Inset photo by Bobbé Christopherson. Mobile Field Trip https://goo.gl/bpcQAU Mississippi River Delta M14_CHRI7119_10_SE_C14.indd 409 06/12/16 1:19 AM https://goo.gl/bpcQAU

- 7. 410 Geosystems Earth’s rivers and waterways form vast arterial net-works that drain the continents. Even though this volume is only 0.003% of all freshwater, the work per- formed by this energetic flow makes it an important natural agent of landmass denudation. Rivers shape the landscape by removing the products of weathering, mass movement, and erosion and transporting them downstream. Remember from Chapter 8 that hydrology is the sci- ence of water at and below Earth’s surface. Processes that are related expressly to streams and rivers are termed fluvial (from the Latin fluvius, meaning “river”). The terms river and stream share some overlap in usage. Spe- cifically, the term river is applied to the trunk or main stream of the network of tributaries forming a river sys- tem. Stream is a more general term for water flowing in a channel and is not necessarily related to size. Fluvial systems, like all natural systems, have characteristic pro- cesses and produce recognizable landforms. The ongoing interaction between erosion, transpor- tation, and deposition in a river system produces fluvial landscapes. Erosion in fluvial systems is the process by which water dislodges, dissolves, or removes weath- ered surface material. This material is then transported to new locations, where it is laid down in the process of deposition. Running water is an important erosional force; in fact, in desert landscapes it is the most signifi- cant agent of erosion even though precipitation events are infrequent. We discuss fluvial processes in arid land- scapes in Chapter 15. Rivers also serve society in many ways. They provide us with essential water supplies; dilute, and transport

- 8. wastes; provide critical cooling water for industry; and form critical transportation networks. Throughout his- tory, civilizations have settled along rivers to farm the fer - tile soils formed by river deposits. These areas continue to be important sites of human activity and settlement, plac- ing lives and property at risk during floods (Figure 14.1). Drainage Basins Streams, which come together to form river systems, lie within drainage basins, the portions of landscape from which they receive their water. Every stream has its own drainage basin, or watershed, ranging in size from tiny to vast. A major drainage basin system is made up of many smaller drainage basins, each of which gathers and delivers its runoff and sediment to a larger basin, even- tually concentrating the volume into the main stream. Figure 14.2 illustrates the drainage basin of the Amazon River, from headwaters to the river’s mouth (where the river meets the ocean). The Amazon carries millions of tons of sediment through the drainage basin, which is as large as the Australian continent. Drainage Divides In any drainage basin, water initially moves downslope as overland flow, which takes two forms: It can move as A flooding river carries not only water but also sediment and debris. When a river overflows its banks into human develop- ments, the flow can pick up vehicles and knock houses off their foundations. As the floodwaters recede, debris such as trees come to rest and sediment is deposited over most surfaces, including the interiors of houses. In June 2016, flooding in West Virginia caused

- 9. extensive damage, 23 fatalities, and left residents cleaning up a land- scape of mud. everydaygeosystems What kind of damage occurs during a river flood? ◀ Figure 14.1 The aftermath of flooding along the Elk River, Clendenin, West Virginia, in June 2016. [Ty Wright/Getty Images.] M14_CHRI7119_10_SE_C14.indd 410 24/11/16 12:10 PM Chapter 14 River Systems 411 0 200 400 KILOMETERS0 200 400 MILES Amazon River basin Mouth of Amazon River Amazon River PACIFIC OCEAN

- 10. ATLANTIC OCEAN A n d e s M o u n t a i n s Elevation in m (ft) 250 (820) 0 (0) 750 (2460) 1500 (4920) 3000

- 11. (9840) 4500 (14,760) ▲Figure 14.2 Amazon River drainage basin and mouth. [NASA SRTM image by Jesse Allen, University of Maryland, Global Land Cover Facility; stream data World Wildlife Fund, HydroSHEDS project (see http:// hydrosheds.cr.usgs.gov/).] Interfluves Drainage divide Drainage basin Drainage basin Drainage divide Drainage divide Drainage divide Valley Valley Rill Gully Shee tflow ▶ Figure 14.3 Drainage divides. A drainage

- 12. divide separates drainage basins. georeport 14.1 Locating the source of the Amazon Over the past several centuries, scientists and explorers have designated at least six different sources as the true beginning of the Ama- zon River. In the 1970s, southwest Peru’s Apurímac River was deemed the longest tributary stream, and in 2000, Lake Ticlla Cocha on the slopes of Mount Mismi was named as the Apurimac's source. Then in 2014, a team of kayakers used GPS tracking data and satellite images to determine that the Mantaro River, also in southwest Peru, is the longest upstream extension of the Amazon River. However, the new claim remains under debate. sheetflow, a thin film spread over the ground surface, and it can concentrate in rills, small-scale grooves in the land- scape made by the downslope move- ment of water. Rills may develop into deeper gullies and then into stream channels leading to the valley floor. The high ground that separates one valley from another and directs sheetflow is called an interfluve (Figure 14.3). Ridges act as drainage divides that define the catchment, or water-receiving, area of every drain- age basin; such ridges are the dividing lines that control into which basin the surface runoff drains. M14_CHRI7119_10_SE_C14.indd 411 24/11/16 12:10 PM

- 13. http://hydrosheds.cr.usgs.gov/).] 412 Geosystems A special class of drainage divides, continental divides, separate drainage basins that empty into dif- ferent bodies of water surrounding a continent (Figure 14.4). For North America, these bodies are the Pacific Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic Ocean, Hudson Bay, and the Arctic Ocean. These divides form water- resource regions and provide a spatial framework for water-management planning. In North America, the con- tinental divide separating the Pacific and Gulf/Atlantic basins runs the length of the Rocky Mountains, reaching its highest point in Colorado at the summit of Gray’s Peak at 4352 m (14,278 ft) elevation (Figure 14.5). As discussed in Geosystems Now, the great Mississippi–Missouri–Ohio River system drains 41% of the continental United States. Within this basin, rain- fall in northern Pennsylvania feeds hundreds of small streams that flow into the Allegheny River. At the same time, rainfall in western Pennsylvania feeds hundreds of streams that flow into the Monongahela River. The two rivers then join at Pittsburgh to form the Ohio River. The Ohio connects with the Mis- sissippi River, which eventually flows to the Gulf of Mexico. Each contributing tributary, large or small, adds its discharge and sedi- ment load to the larger river. In our example, sediment weathered and eroded in Pennsyl- vania is transported thousands of kilometers and accumulates on the floor of the Gulf

- 14. of Mexico, where it forms the Mississippi River delta. Internal Drainage The ultimate outlet for most drainage ba- sins is the ocean. In some regions, however, stream drainage does not reach the ocean. Instead, the water leaves the drainage basin by means of evaporation or subsurface gravi- tational flow. Such basins are described as having internal drainage. Regions of inter- nal drainage occur in Asia, Africa, Australia, Mexico, and the western United States in Nevada and Utah (discussed in Chapter 15). An example within this region is the Hum- boldt River, which flows westward across Nevada and eventually disappears into the Humboldt Sink as a result of evaporation and seepage losses to groundwater. The area surrounding Utah’s Great Salt Lake, out- let for many streams draining the Wasatch Mountains, also exemplifies internal drain- age, since its only outlet is evaporation. In- ternal drainage is also a characteristic of the Dead Sea region in the Middle East and the region around the Aral Sea and Caspian Sea in Asia (Figure 14.6). Drainage Basins as Open Systems Drainage basins are open systems. Inputs include pre- cipitation and the minerals and rocks of the regional geology. Energy and materials are redistributed as the stream constantly adjusts to its landscape. System out- puts of water and sediment disperse through the mouth of the stream or river into a lake, another stream or river, or the ocean.

- 15. Change that occurs in any portion of a drainage basin can affect the entire system. For example, the building of a dam not only affects the immediate stream envi- ronment around the structure, but can also change the movement of water and sediment for hundreds of miles downstream. Natural processes such as floods can also push river systems to thresholds, where banks collapse or channels change course. Throughout changing condi- tions, a river system constantly strives for equilibrium among the interacting variables of discharge, chan- nel steepness, channel shape, and sediment load, all of which are discussed in the chapter ahead. (a) Loveland Pass, Colorado, lies along the continental divide between the Pacific and Gulf/Atlantic drainage basins. (b) A backpacker approaches the continental divide at Cutbank Pass, Glacier National Park, Montana. ▲Figure 14.4 The U.S. Continental Divide, Colorado and Montana. [(a) Erika Nusser/Alamy. (b) Design Pics Inc./Alamy.] M14_CHRI7119_10_SE_C14.indd 412 24/11/16 12:10 PM Chapter 14 River Systems 413 No rth A tla

- 18. 20°N 30°N 40°N 50°N 70°N 80°N 120°W130°W 80°W Ar cti c Ci rcl e Tropic of Cancer Bering Sea Gulf of Alaska Labrador Sea Hudson

- 19. Bay Baffin Bay Beaufort Sea Gulf of Mexico ARCTIC OCEAN ATLANTIC OCEAN ARCTIC OCEAN PACIFIC OCEAN C A L IF O R N I A NELSON

- 23. COLORADO ARCTIC COAST AND ISLANDS 0 250 500 KILOMETERS0 250 500 MILES DRAINAGE BASIN DISCHARGE CANADA: Hudson Bay 682,000 (553) Atlantic 670,000 (544) Pacific 602,000 (488) Arctic 440,000 (356) Gulf of Mexico 105 (0.9) UNITED STATES: Gulf/Atlantic 718 (886,000) Pacific 334 (412,000) Atlantic 293 (361,000) millions acre-feet per year (millions m3 per year) millions m3 per year (millions acre-feet per year) Continental divides ◀ Figure 14.5 Drainage

- 24. basins and continental divides, North America. Continental divides (red lines) separate the major drainage basins that empty through the United States into the Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, and Gulf of Mexico, and to the north, through Canada into Hudson Bay and the Arctic Ocean. Subdividing these major drainage basins are major river basins. [After U.S. Geological Survey; The National Atlas of Canada, 1985, “Energy, Mines, and Resources Canada”; and Environment Canada, Currents of Change— Inquiry on Federal Water Policy—Final Report 1986.] ◀ Figure 14.6 Utah’s Great Salt Lake, part of an interior drainage system. [Delphotos/ Alamy.] M14_CHRI7119_10_SE_C14.indd 413 24/11/16 12:10 PM 414 Geosystems number and length of channels in a given area reflect the

- 25. landscape’s regional geology and topography. For exam- ple, landscapes with underlying materials that are easily erodible will have a higher drainage density than land- scapes of more resistant rock. The drainage pattern is the arrangement of channels in an area. Distinctive patterns can develop based on a combination of factors, including • regional topography and slope inclination, • variations in rock resistance, • climate and hydrology, and • structural controls imposed by the underlying rocks. Consequently, the drainage pattern of any land area on Earth is a remarkable visual summary of every geologic and climatic characteristic of that region. A familiar pattern is dendritic drainage (Figure 14.7a), a treelike pattern (from the Greek word dendron, meaning “tree”) similar to that of many natural systems, such as capillaries in the human circulatory system or the veins in tree leaves. Energy expenditure in the mov- ing of water and sediment through this drainage system is efficient because the total length of the branches is mini - mized. In landscapes with steep slopes, parallel drainage may occur (Figure 14.7b). In some landscapes, drainage patterns alter their characteristics abruptly in response to slope steepness or rock structure (Figure 14.7c). Other drainage patterns are closely tied to geo- logic structure. Around a volcanic mountain or uplifted dome, a radial drainage pattern results when streams flow off a central large peak. New Zealand’s Mount Rua- pehu, an active volcano on the North Island, shows such a radial drainage pattern (Figure 14.8). In a faulted and

- 26. (a) Note the drainage channels flowing off the central peak of Mount Ruapehu, which last erupted in 2007. (b) Radial drainage pattern. ◀ Figure 14.8 Radial drainage on Mount Ruapehu, North Island, New Zealand. This false-color image of the composite vocano shows vegetation as red, the crater lake as light blue, and rocks as brown. [NASA.] Drainage Patterns A primary feature of any drainage basin is its drainage density, determined by dividing the total length of all stream channels in the basin by the area of the basin. The (a) Dendritic drainage pattern. (c) Dendritic and parallel drainage in response to local geology and relief in central Montana. (b) Parallel drainage pattern. Drainage divide ▲Figure 14.7 Dendritic and parallel drainage patterns. [Bobbé Christopherson.] M14_CHRI7119_10_SE_C14.indd 414 24/11/16 12:10 PM Chapter 14 River Systems 415

- 27. (a) A rectangular stream pattern develops in areas with jointed bedrock. (b) A trellis stream pattern develops in areas where the geologic structure is a mix of weak and resistant bedrock (such as in folded landscapes). Ridges of resistant rock Valleys cut in less-resistant rock ▲Figure 14.9 Drainage patterns controlled by geologic structure: rectangular and trellis. S u s q u e h a n n a R

- 28. iv e r As erosion exposes underlying rock with a different structure, the river cuts through ridges of resistant rock rather than flowing around them. Water gap in the eastern United States and in the folded land- scapes of south-central Utah. Some landscapes display a deranged pattern with no clear geometry and no true stream valley. Examples include the glaciated shield re- gions of Canada, northern Europe, and some parts of the U.S. upper Midwest. Occasionally, drainage patterns occur that seem to be in conflict with the landscape through which they flow. For example, a stream may initially develop a channel in horizontal strata deposited on top of up- lifted, folded structures. As the stream erodes into the older folded rock layers, it keeps the original course, downcutting into the rock in a pattern contrary to the structure of the older layers. Such a stream is a super- posed stream, in which a preexisting channel pattern has been imposed upon older underlying rock struc- tures (Figure 14.10). For example, Wills Creek, presently cutting a water gap through Haystack Mountain at Cum- berland, Maryland, is a superposed stream. A water gap is a notch or opening cut by a river through a mountain range and is often an indication that the river is older than the landscape.

- 29. ▲Figure 14.10 The Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, a superposed stream. The Susquehanna River established its course on relatively uniform rock strata that covered more complex geologic structure below. Over time, as the landscape eroded, the river “superposed” its course onto the older structure by cutting through the resistant strata. [Landsat-7, NASA.] WoRkitOut 14.1 Stream Drainage Patterns Choose among dendritic, parallel, radial, rectangular, trellis, and deranged drainage patterns to answer the following questions. 1. Which drainage pattern often occurs in a landscape with a central mountain peak? 2. Which pattern is prominent in the Amazon River basin in Figure 14.2? 3. Which pattern often occurs in landscapes of jointed bedrock? 4. Which pattern occurs in landscapes of folded rock, such as in southern Utah? 5. Which pattern might be found in the Canadian Shield land- scape shown in Figure 12.2? jointed landscape, a rectangular pattern (Figure 14.9a) directs stream courses in patterns of right-angle turns. In dipping or folded topography, the trellis drainage

- 30. pattern develops, influenced by folded rock structures that vary in resistance to erosion (Figure 14.9b). Paral - lel structures direct the principal streams, while smaller dendritic tributary streams are at work on nearby slopes, joining the main streams at right angles, as in a plant trellis. Such drainage is seen in the nearly par - allel mountain folds of the Ridge and Valley Province M14_CHRI7119_10_SE_C14.indd 415 24/11/16 12:10 PM HR_Chapter 14.docx Chapter 14 Presentations to Persuade We are more easily persuaded, in general, by the reasons that we ourselves discovers than by those which are given to us by others. Pascal For every sale you miss because you’re too enthusiastic, you will miss a hundred because you’re not enthusiastic enough. Zig Ziglar Getting Started No doubt there has been a time when you wanted something from your parents, your supervisor, or your friends, and you thought about how you were going to present your request. But do you think about how often people—including people you have never met and never will meet—want something from you? When you watch television, advertisements reach out for your attention, whether you watch them or not. When you use the Internet, pop-up advertisements often appear. Living in the United States, and many parts of the world, means that you have been surrounded, even inundated, by persuasive messages. Mass media in general and television in particular make a significant

- 31. impact you will certainly recognize. Consider these facts: · The average person sees between four hundred and six hundred ads per day—that is forty million to fifty million by the time he or she is sixty years old. One of every eleven commercials has a direct message about beauty.[1] · By age eighteen, the average American teenager will have spent more time watching television—25,000 hours—than learning in a classroom.[2] · An analysis of music videos found that nearly one-fourth of all MTV videos portray overt violence, with attractive role models being aggressors in more than 80 percent of the violent videos.[3] · Forty percent of nine- and ten-year-old girls have tried to lose weight, according to an ongoing study funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. [4] · A 1996 study found that the amount of time an adolescent watches soaps, movies, and music videos is associated with their degree of body dissatisfaction and desire to be thin. [5] · Identification with television stars (for girls and boys), models (girls), or athletes (boys) positively correlated with body dissatisfaction. [6] · At age thirteen, 53 percent of American girls are “unhappy with their bodies.” This grows to 78 percent by the time they reach seventeen. [7] · By age eighteen, the average American teenager will witness on television 200,000 acts of violence, including 40,000 murders. [8] Mass communication contains persuasive messages, often called propaganda, in narrative form, in stories and even in presidential speeches. When President Bush made his case for invading Iraq, his speeches incorporated many of the techniques we’ll cover in this chapter. Your local city council often involves dialogue, and persuasive speeches, to determine zoning issues, resource allocation, and even spending priorities. You yourself have learned many of the techniques by trial and error

- 32. and through imitation. If you ever wanted the keys to your parents’ car for a special occasion, you used the principles of persuasion to reach your goal. [1] Raimondo, M. (2010). About-face facts on the media. About-face. Retrieved fromhttp://www.about- face.org/r/facts/media.shtml [2] Ship, J. (2005, December). Entertain. Inspire. Empower. How to speak a teen’s language, even if you’re not one. ChangeThis. Retrieved fromhttp://www.changethis.com/pdf/20.02.TeensLanguage.pdf [3] DuRant, R. H. (1997). Tobacco and alcohol use behaviors portrayed in music videos: Content analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 1131–1135. [4] Body image and nutrition: Fast facts. (2009). Teen Health and the Media. Retrieved from http://depts.washington.edu/thmedia/view.cgi?section=bod yimage&page=fastfacts [5] Tiggemann, M., & Pickering, A. S. (1996). Role of television in adolescent women’s body: Dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 20, 199–203. [6] Hofschire, L. J., & Greenberg, B. S. (2002). Media’s impact on adolescent’s body dissatisfaction. In D. Brown, J. R. Steele, & K. Walsh-Childers (Eds.), Sexual Teens, Sexual Media. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [7] Brumberg, J. J. (1997). The body project: An intimate history of American girls. New York, NY: Random House. [8] Huston, A. C., et al. (1992). Big world, small screen: The role of television in American society. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 14.1 What Is Persuasion? LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the importance of persuasion.

- 33. 2. Describe similarities and differences between persuasion and motivation. Persuasion is an act or process of presenting arguments to move, motivate, or change your audience. Aristotle taught that rhetoric, or the art of public speaking, involves the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.[1] In the case of President Obama, he may have appealed to your sense of duty and national values. In persuading your parents to lend you the car keys, you may have asked one parent instead of the other, calculating the probable response of each parent and electing to approach the one who was more likely to adopt your position (and give you the keys). Persuasion can be implicit or explicit and can have both positive and negative effects. In this chapter we’ll discuss the importance of ethics, as we have in previous chapters, when presenting your audience with arguments in order to motivate them to adopt your view, consider your points, or change their behavior. Motivation is distinct from persuasion in that it involves the force, stimulus, or influence to bring about change. Persuasion is the process, and motivation is the compelling stimulus that encourages your audience to change their beliefs or behavior, to adopt your position, or to consider your arguments. Why think of yourself as fat or thin? Why should you choose to spay or neuter your pet? Messages about what is beautiful, or what is the right thing to do in terms of your pet, involve persuasion, and the motivation compels you to do something. Another way to relate to motivation also can be drawn from the mass media. Perhaps you have watched programs like Law and Order, Cold Case, or CSI where the police detectives have many of the facts of the case, but they search for motive. They want to establish motive in the case to provide the proverbial “missing piece of the puzzle.” They want to know why someone would act in a certain manner. You’ll be asking your audience

- 34. to consider your position and provide both persuasive arguments and motivation for them to contemplate. You may have heard a speech where the speaker tried to persuade you, tried to motivate you to change, and you resisted the message. Use this perspective to your advantage and consider why an audience should be motivated, and you may find the most compelling examples or points. Relying on positions like “I believe it, so you should too,” “Trust me, I know what is right,” or “It’s the right thing to do” may not be explicitly stated but may be used with limited effectiveness. Why should the audience believe, trust, or consider the position “right?” Keep an audience- centered perspective as you consider your persuasive speech to increase your effectiveness. You may think initially that many people in your audience would naturally support your position in favor of spaying or neutering your pet. After careful consideration and audience analysis, however, you may find that people are more divergent in their views. Some audience members may already agree with your view, but others may be hostile to the idea for various reasons. Some people may be neutral on the topic and look to you to consider the salient arguments. Your audience will have a range of opinions, attitudes, and beliefs across a range from hostile to agreement. Rather than view this speech as a means to get everyone to agree with you, look at the concept of measurable gain, a system of assessing the extent to which audience members respond to a persuasive message. You may reinforce existing beliefs in the members of the audience that agree with you and do a fine job of persuasion. You may also get hostile members of the audience to consider one of your arguments, and move from a hostile position to one that is more neutral or ambivalent. The goal in each case is to move the audience members toward your position. Some change may be small but measurable, and that is considered gain. The next time a hostile

- 35. audience member considers the issue, they may be more open to it. Figure 14.1 "Measurable Gain" is a useful diagram to illustrate this concept. Figure 14.1Measurable Gain Edward Hall[2] also underlines this point when discussing the importance of context. The situation in which a conversation occurs provides a lot of meaning and understanding for the participants in some cultures. In Japan, for example, the context, such as a business setting, says a great deal about the conversation and the meaning to the words and expressions within that context. In the United States, however, the concept of a workplace or a business meeting is less structured, and the context offers less meaning and understa nding. Cultures that value context highly are aptly called high-context cultures. Those that value context to a lesser degree are called low-context cultures. These divergent perspectives influence the process of persuasion and are worthy of your consideration when planning your speech. If your audience is primarily high- context, you may be able to rely on many cultural norms as you proceed, but in a low-context culture, like the United States, you’ll be expected to provide structure and clearly outline your position and expectations. This ability to understand motivation and context is key to good communication, and one that we will examine throughout this chapter. [1] Covino, W. A., & Jolliffe, D. A. (1995). Rhetoric: Concepts, definitions, boundaries. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [2] Hall, E. (1966). The hidden dimension. New York, NY: Doubleday. 14.2 Principles of Persuasion LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1. Identify and demonstrate how to use six principles of persuasion.

- 36. What is the best way to succeed in persuading your listeners? There is no one “correct” answer, but many experts have studied persuasion and observed what works and what doesn’t work. Social psychologist Robert Cialdini[1] offers us six principles of persuasion that are powerful and effective: 1. Reciprocity 2. Scarcity 3. Authority 4. Commitment and consistency 5. Consensus 6. Liking You will find these principles both universal and adaptable to a myriad of contexts and environments. Recognizing when each principle is in operation will allow you to leverage the inherent social norms and expectations to your advantage, and enhance your sales position. Principle of Reciprocity Reciprocity is the mutual expectation for exchange of value or service. In all cultures, when one person gives something, the receiver is expected to reciprocate, even if only by saying “thank you.” There is a moment when the giver has power and influence over the receiver, and if the exchange is dismissed as irrelevant by the giver the moment is lost. In business this principle has several applications. If you are in customer service and go out of your way to meet the customer’s need, you are appealing to the principle of reciprocity with the knowledge that all humans perceive the need to reciprocate—in this case, by increasing the likelihood of making a purchase from you because you were especially helpful. Reciprocity builds trust and the relationship develops, reinforcing everything from personal to brand loyalty. By taking the lead and giving, you build in a moment where people will feel compelled from social norms and customs to give back. Principle of Scarcity

- 37. You want what you can’t have, and it’s universal. People are naturally attracted to the exclusive, the rare, the unusual, and the unique. If they are convinced that they need to act now or it will disappear, they are motivated to action. Scarcity is the perception of inadequate supply or a limited resource. For a sales representative, scarcity may be a key selling point—the particular car, or theater tickets, or pair of shoes you are considering may be sold to someone else if you delay making a decision. By reminding customers not only of what they stand to gain but also of what they stand to lose, the representative increases the chances that the customer will make the shift from contemplation to action and decide to close the sale. Principle of Authority Trust is central to the purchase decision. Whom does a customer turn to? A salesperson may be part of the process, but an endorsement by an authority holds credibility that no one with a vested interest can ever attain. Knowledge of a product, field, trends in the field, and even research can make a salesperson more effective by the appeal to the principle of authority. It may seem like extra work to educate your customers, but you need to reveal your expertise to gain credibility. We can borrow a measure of credibility by relating what experts have indicated about a product, service, market, or trend, and our awareness of competing viewpoints allows us insight that is valuable to the customer. Reading the manual of a product is not sufficient to gain expertise—you have to do extra homework. The principal of authority involves referencing experts and expertise. Principle of Commitment and Consistency Oral communication can be slippery in memory. What we said at one moment or another, unless recorded, can be hard to recall. Even a handshake, once the symbol of agreement across almost every culture, has lost some of its symbolic meaning and

- 38. social regard. In many cultures, the written word holds special meaning. If we write it down, or if we sign something, we are more likely to follow through. By extension, even if the customer won’t be writing anything down, if you do so in front of them, it can appeal to the principle of commitment and consistency and bring the social norm of honoring one’s word to bear at the moment of purchase. Principle of Consensus Testimonials, or first person reports on experience with a product or service, can be highly persuasive. People often look to each other when making a purchase decision, and the herd mentality is a powerful force across humanity: if “everybody else” thinks this product is great, it must be great. We often choose the path of the herd, particularly when we lack adequate information. Leverage testimonials from clients to attract more clients by making them part of your team. The principle of consensus involves the tendency of the individual to follow the lead of the group or peers. Principle of Liking Safety is the twin of trust as a foundation element for effective communication. If we feel safe, we are more likely to interact and communicate. We tend to be attracted to people who communicate to us that they like us, and who make us feel good about ourselves. Given a choice, these are the people with whom we are likely to associate. Physical attractiveness has long been known to be persuasive, but similarity is also quite effective. We are drawn to people who are like us, or who we perceive ourselves to be, and often make those judgments based on external characteristics like dress, age, sex, race, ethnicity, and perceptions of socioeconomic status. The principle of liking involves the perception of safety and belonging in communication. [1] Cialdini, R. (1993). Influence. New York, NY: Quill.

- 39. 14.3 Functions of the Presentation to Persuade LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1. Identify and demonstrate the effective use of five functions of speaking to persuade. What does a presentation to persuade do? There is a range of functions to consider, and they may overlap or you may incorporate more than one as you present. We will discuss how to · stimulate, · convince, · call to action, · increase consideration, and · develop tolerance of alternate perspectives. We will also examine how each of these functions influences the process of persuasion. Stimulate When you focus on stimulation as the goal or operational function of your speech, you want to reinforce existing beliefs, intensify them, and bring them to the forefront. Perhaps you’ve been concerned with global warming for quite some time. Many people in the audience may not know about the melting polar ice caps and the loss of significant ice shelves in Antarctica, including part of the Ross Ice Shelf, an iceberg almost 20 miles wide and 124 miles long, more than twice the size of Rhode Island. They may be unaware of how many ice shelves have broken off, the 6 percent drop in global phytoplankton (the basis of many food chains), and the effects of the introduction of fresh water to the oceans. By presenting these facts, you will reinforce existing beliefs, intensify them, and bring the issue to the surface. You might consider the foundation of common ground and commonly held beliefs, and then introduce information that a mainstream audience may not be aware of that supports that common ground as a strategy to stimulate.

- 40. Convince In a persuasive speech, the goal is to change the attitudes, beliefs, values, or judgments of your audience. If we look back at the idea of motive, in this speech the prosecuting attorney would try to convince the jury members that the defendant is guilty beyond reasonable doubt. He or she may discuss motive, present facts, all with the goal to convince the jury to believe or find that his or her position is true. In the film The Day After Tomorrow, Dennis Quaid stars as a paleoclimatologist who unsuccessfully tries to convince the U.S. vice president that a sudden climate change is about to occur. In the film, much like real life, the vice president listens to Quaid’s position with his own bias in mind, listening for only points that reinforce his point of view while rejecting points that do not. Audience members will also hold beliefs and are likely to involve their own personal bias. Your goal is to get them to agree with your position, so you will need to plan a range of points and examples to get audience members to consider your topic. Perhaps you present Dennis Quaid’s argument that loss of the North Atlantic Current will drastically change our climate, clearly establishing the problem for the audience. You might cite the review by a professor, for example, who states in reputable science magazine that the film’s depiction of a climate change has a chance of happening, but that the timetable is more on the order of ten years, not seven days as depicted in the film. You then describe a range of possible solutions. If the audience comes to a mental agreement that a problem exists, they will look to you asking, “What are the options?” Then you may indicate a solution that is a better alternative, recommending future action. Call to Action In this speech, you are calling your audience to action. You are stating that it’s not about stimulating interest to reinforce and

- 41. accentuate beliefs, or convincing an audience of a viewpoint that you hold, but instead that you want to see your listeners change their behavior. If you were in sales at Toyota, you might incorporate our previous example on global warming to reinforce, and then make a call to action (make a purchase decision), when presenting the Prius hybrid (gas-electric) automobile. The economics, even at current gas prices, might not completely justify the difference in price between a hybrid and a nonhybrid car. However, if you as the salesperson can make a convincing argument that choosing a hybrid car is the right and responsible decision, you may be more likely to get the customer to act. The persuasive speech that focuses on action often generates curiosity, clarifies a problem, and as we have seen, proposes a range of solutions. They key difference here is there is a clear link to action associated with the solutions. Solution s lead us to considering the goals of action. These goals address the question, “What do I want the audience to do as a result of being engaged by my speech?” The goals of action include adoption, discontinuance, deterrence, and continuance. Adoption means the speaker wants to persuade the audience to take on a new way of thinking, or adopt a new idea. Examples could include buying a new product, voting for a new candidate, or deciding to donate blood. The key is that the audience member adopts, or takes on, a new view, action, or habit.

- 42. Discontinuance involves the speaker persuading the audience to stop doing something what they have been doing, such as smoking. Rather than take on a new habit or action, the speaker is asking the audience member to stop an existing behavior or idea. As such, discontinuance is in some ways the opposite of adoption. Deterrence is a call action that focuses on persuading audience not to start something if they haven’t already started. Perhaps many people in the audience have never tried illicit drugs, or have not gotten behind the wheel of a car while intoxicated. The goal of action in this case would be to deter, or encourage the audience members to refrain from starting or initiating the behavior. Finally, with continuance, the speaker aims to persuade the audience to continue doing what they have been doing, such as reelect a candidate, keep buying product, or staying in school to get an education. A speaker may choose to address more than one of these goals of action, depending on the audience analysis. If the audience is largely agreeable and supportive, you may find continuance to be one goal, while adoption is secondary.

- 43. These goals serve to guide you in the development of solution steps.