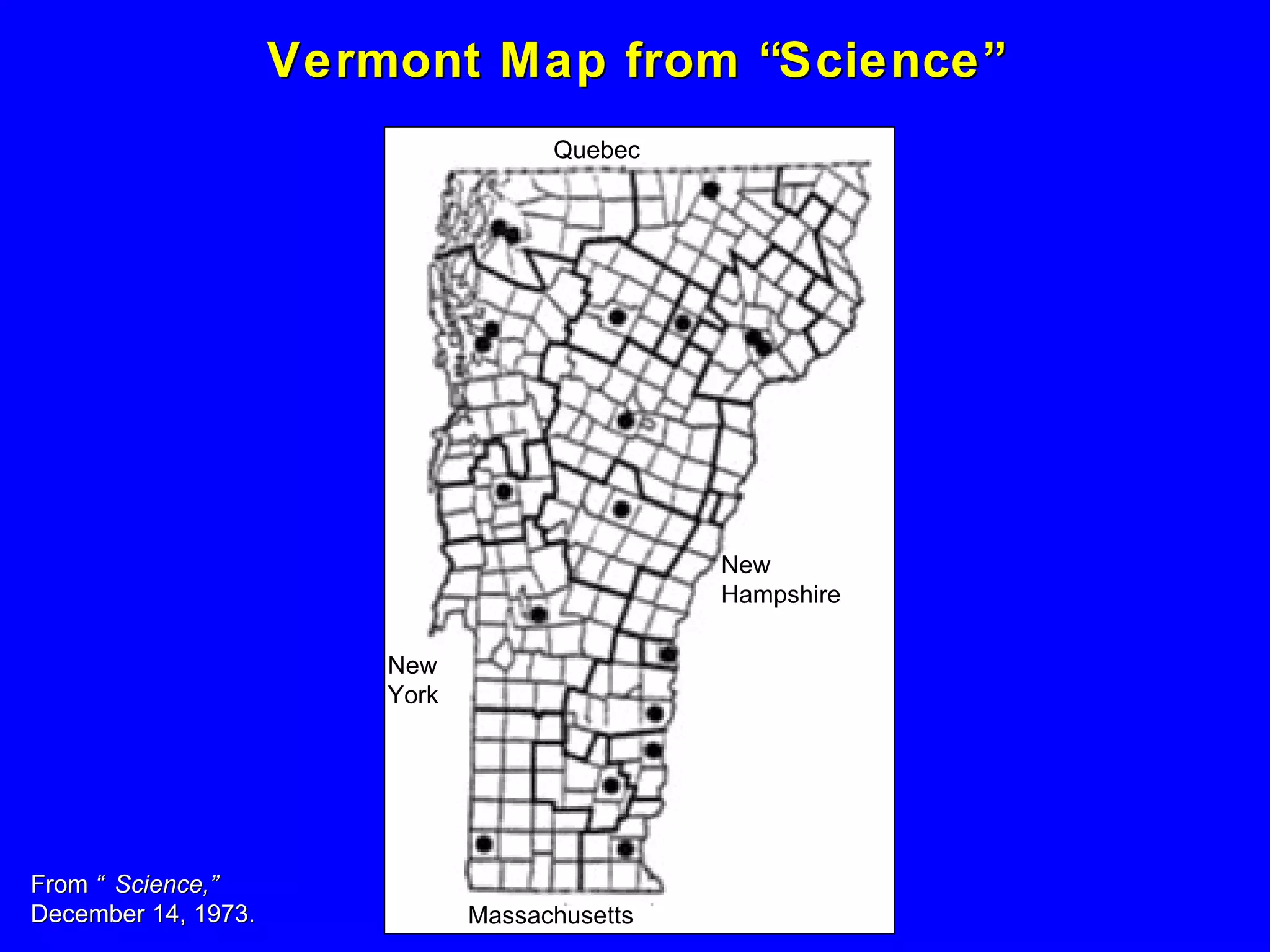

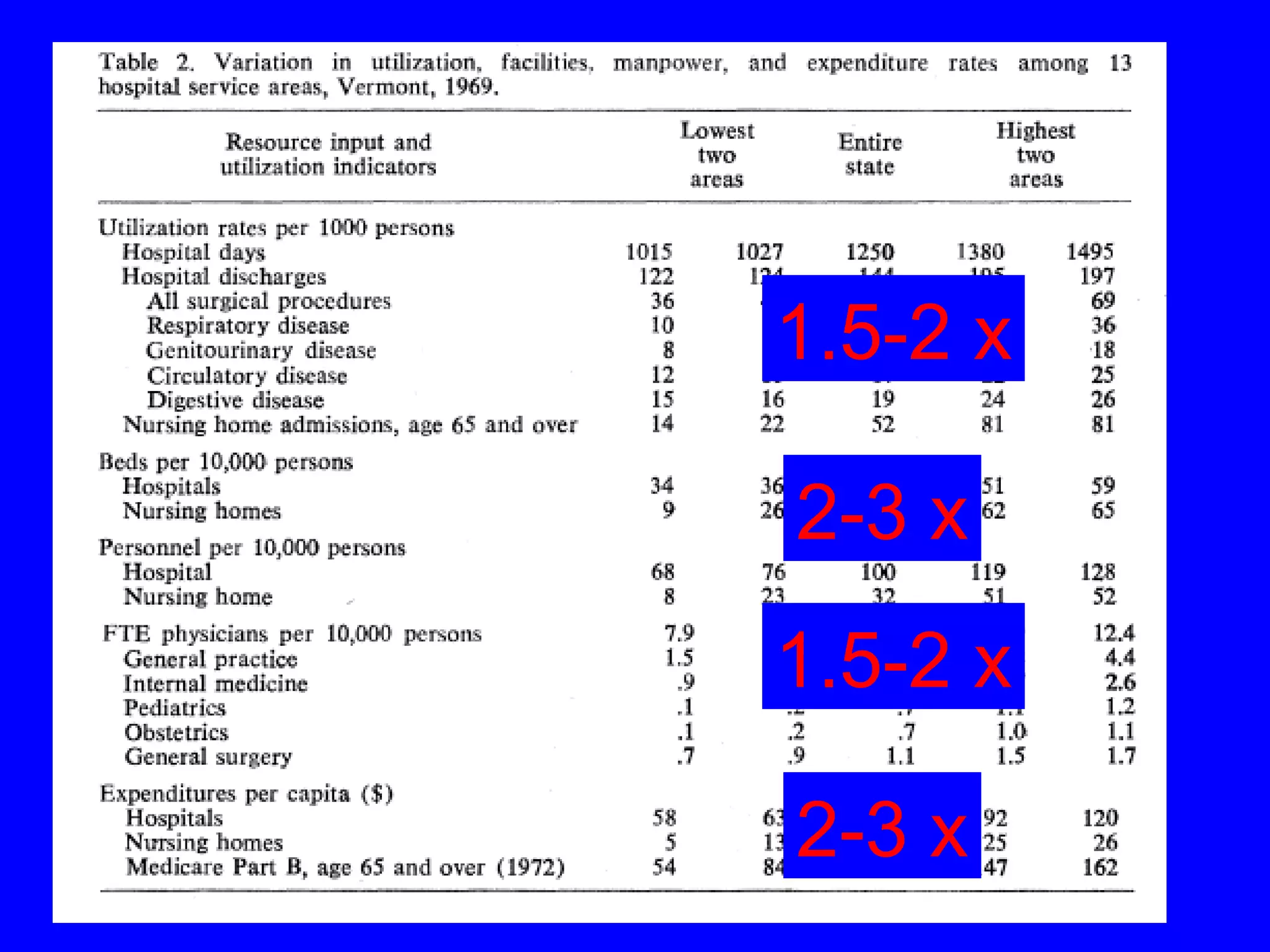

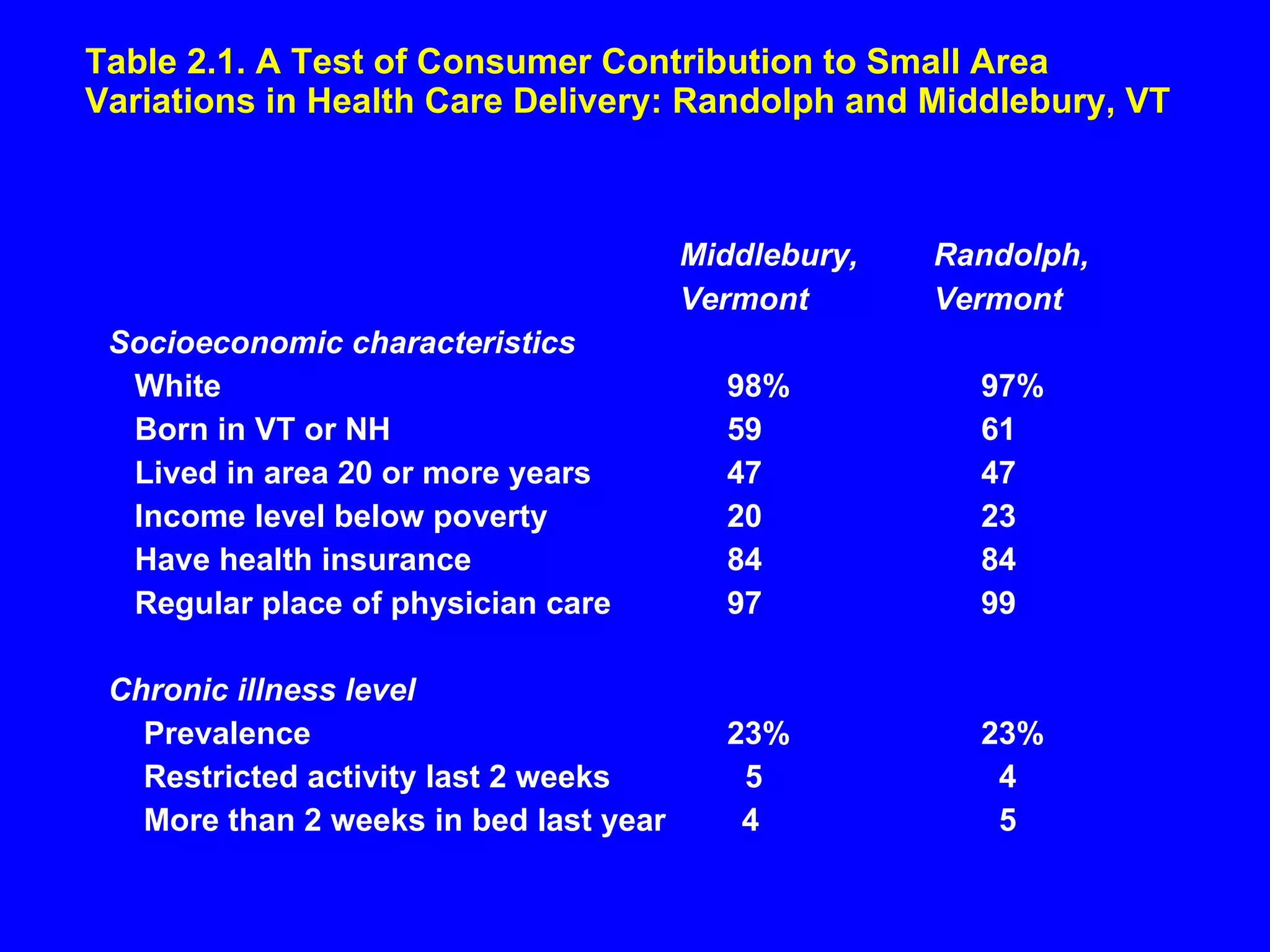

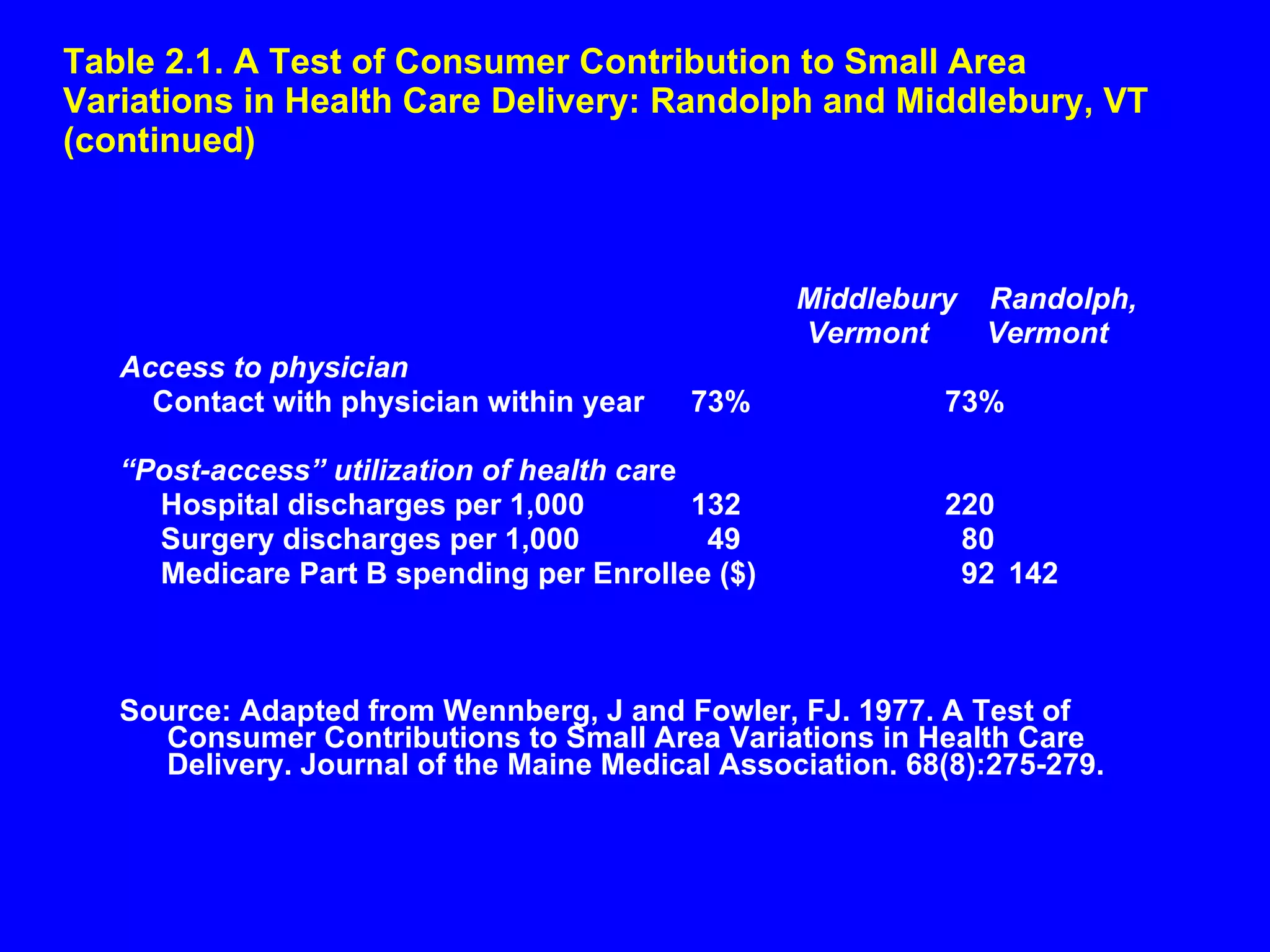

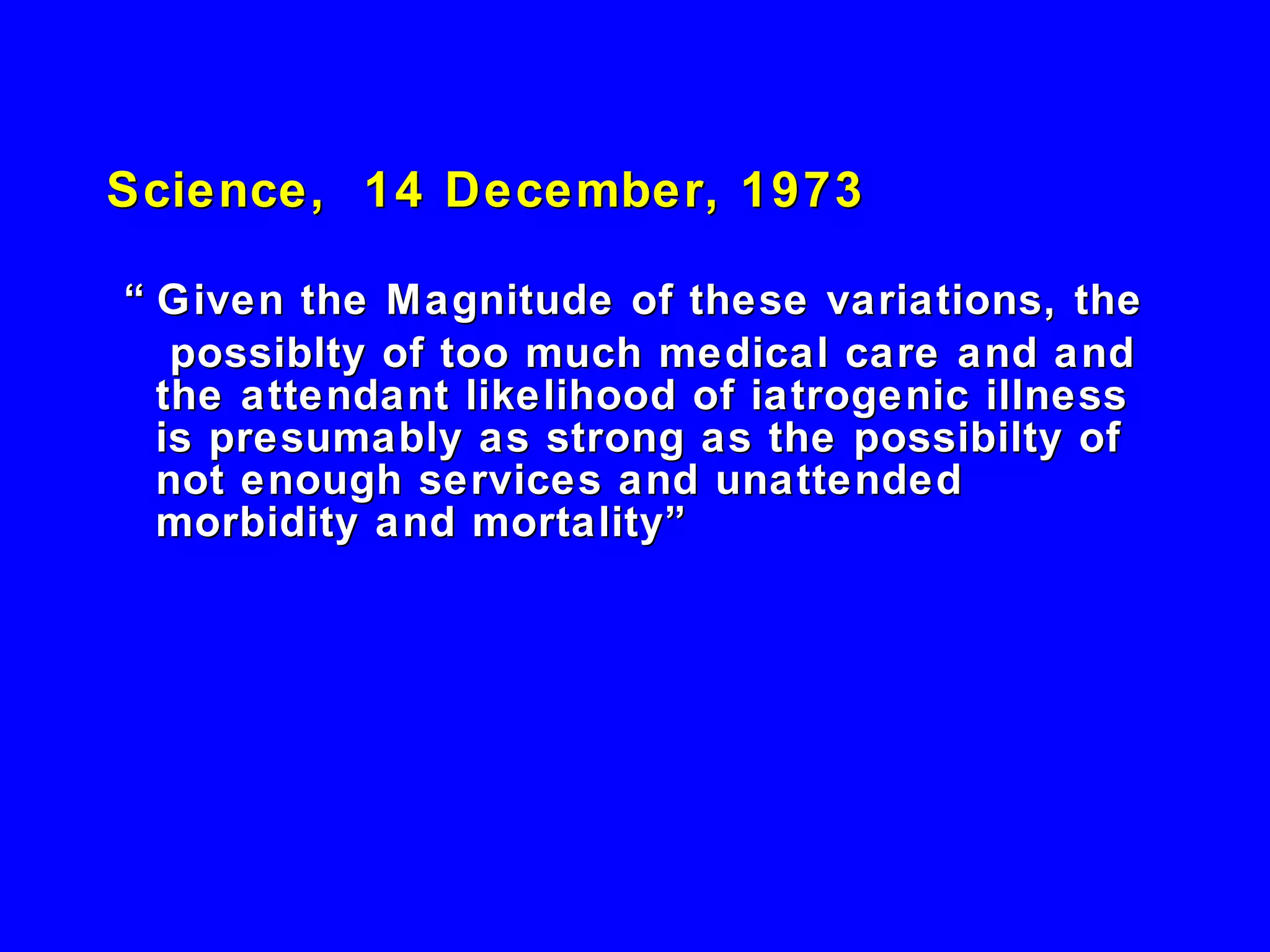

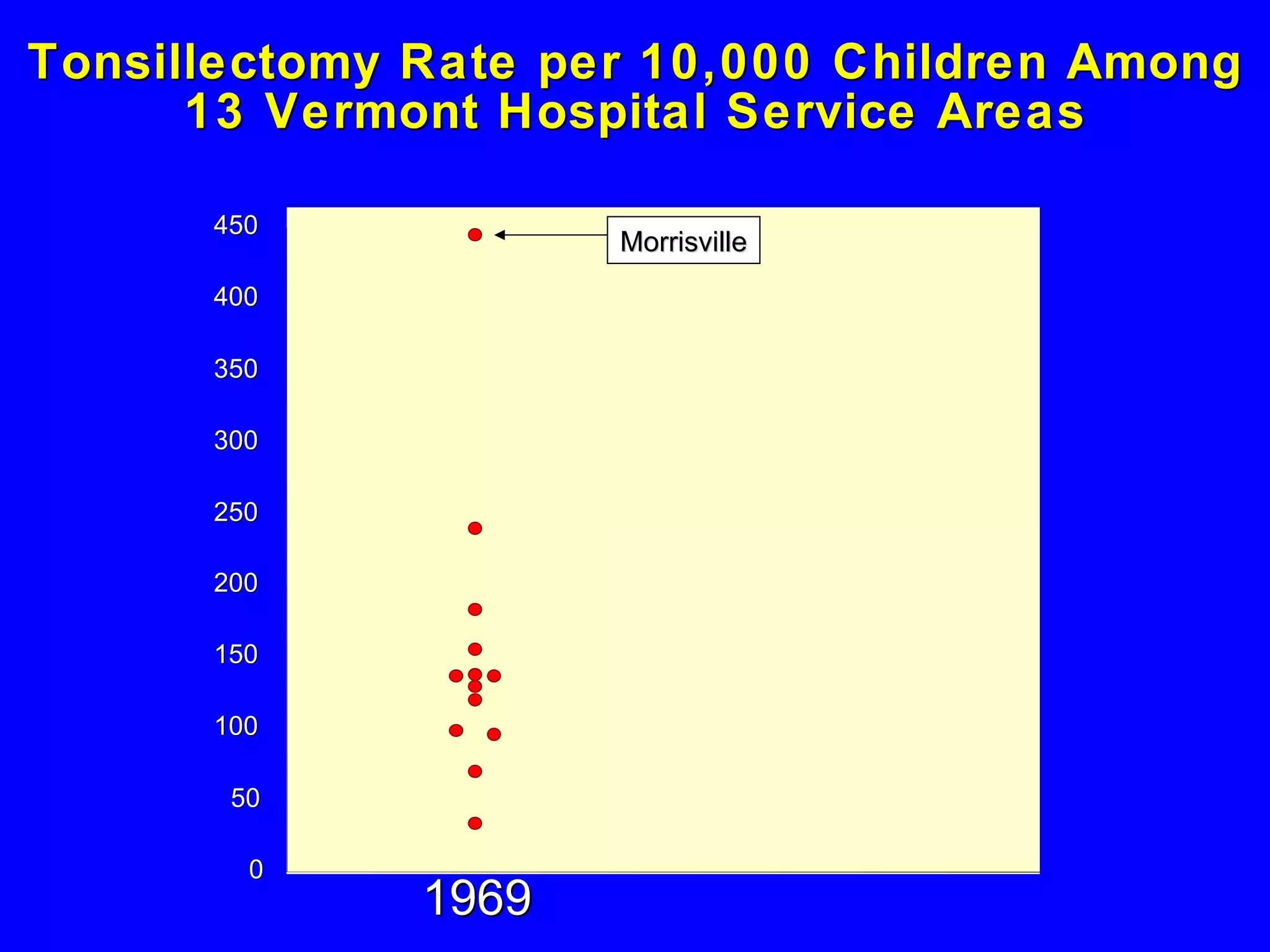

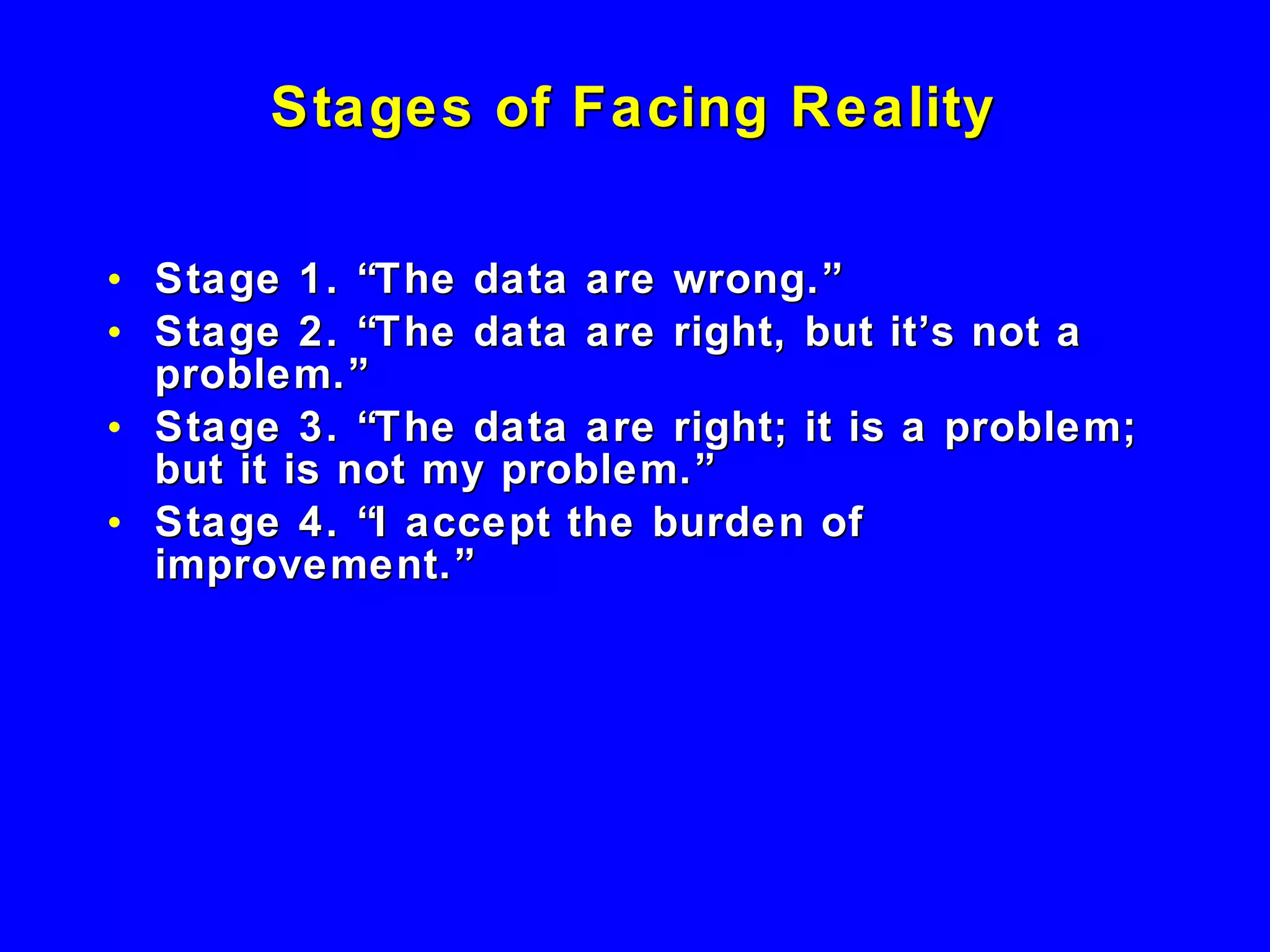

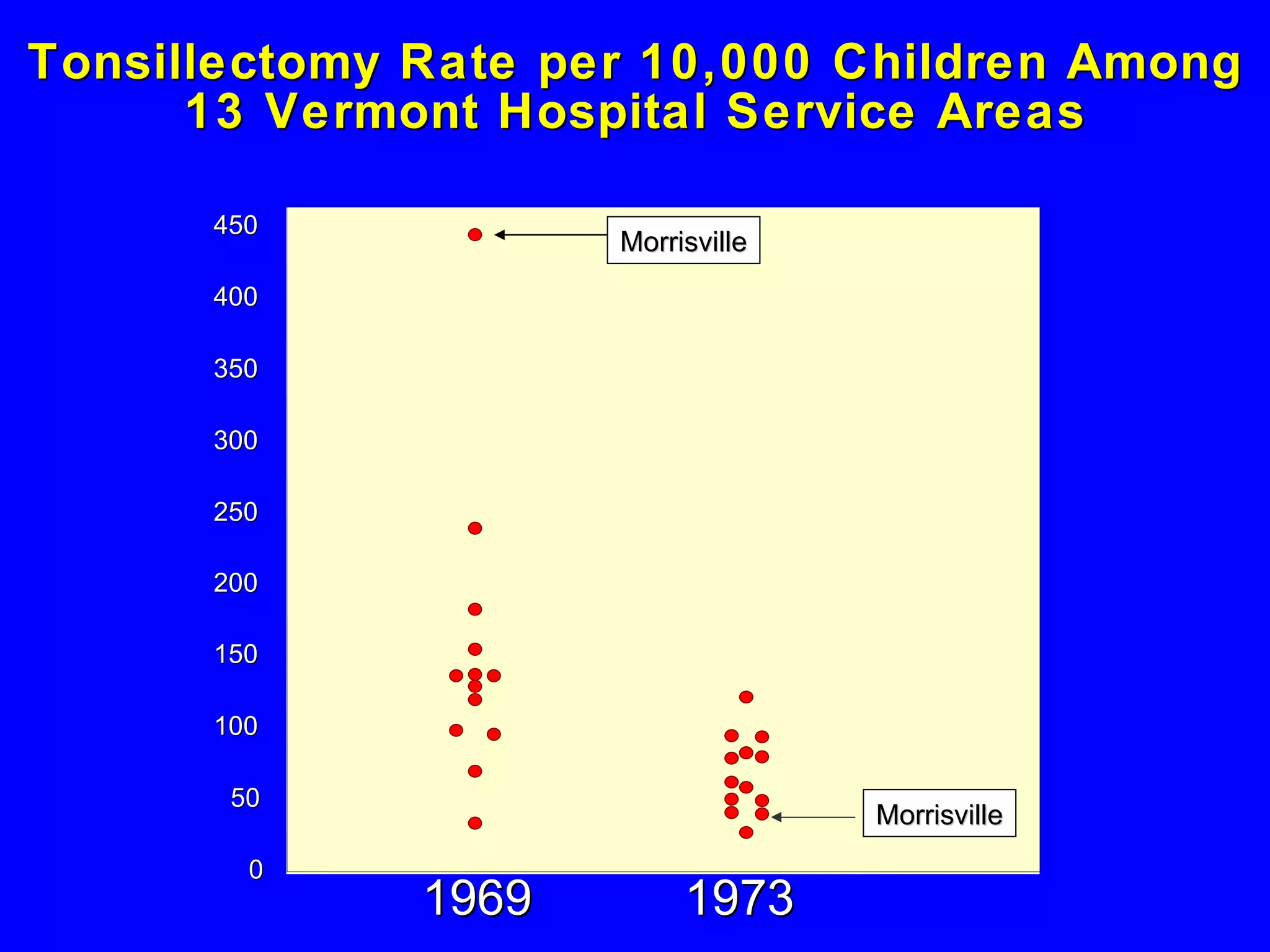

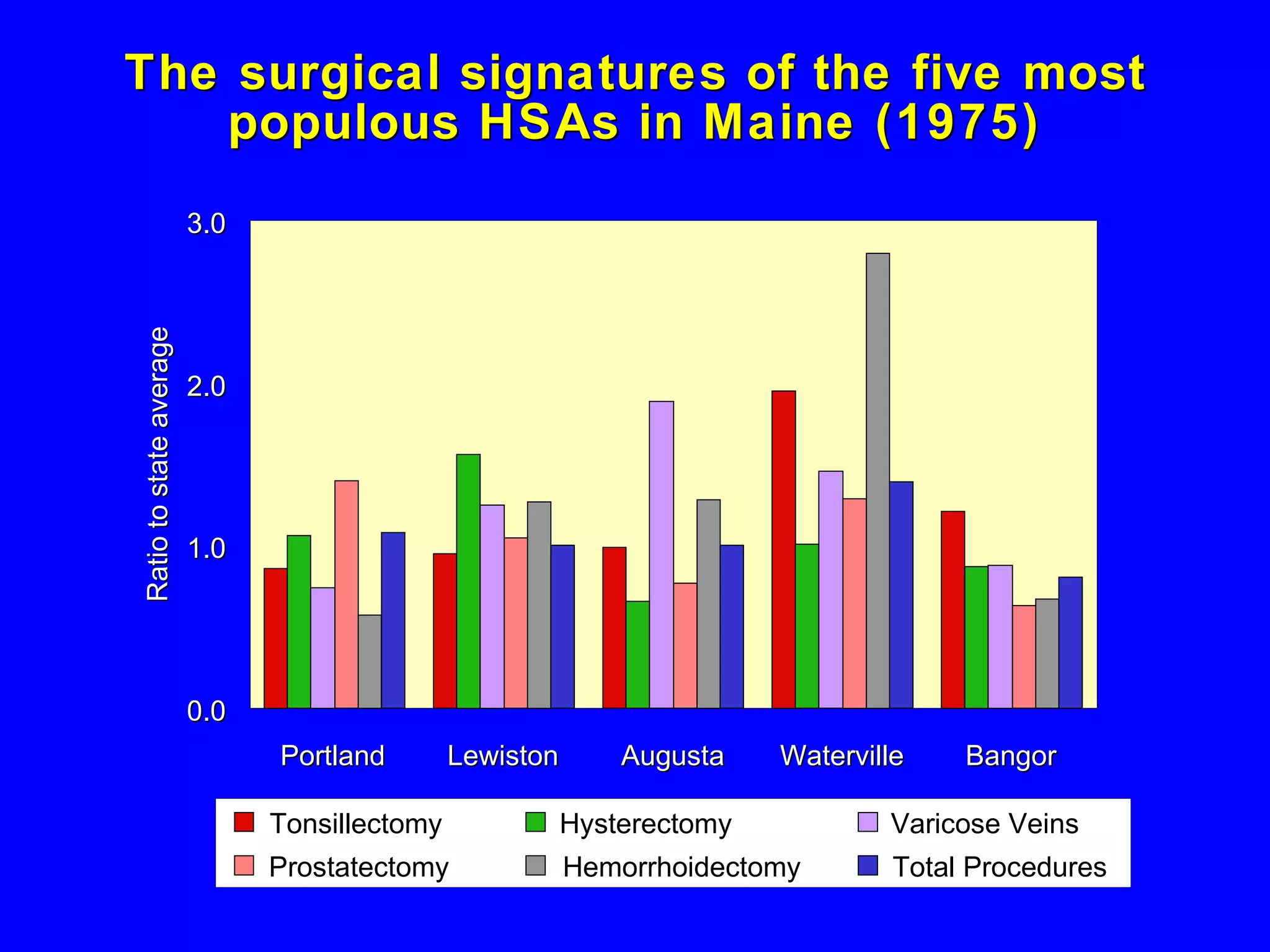

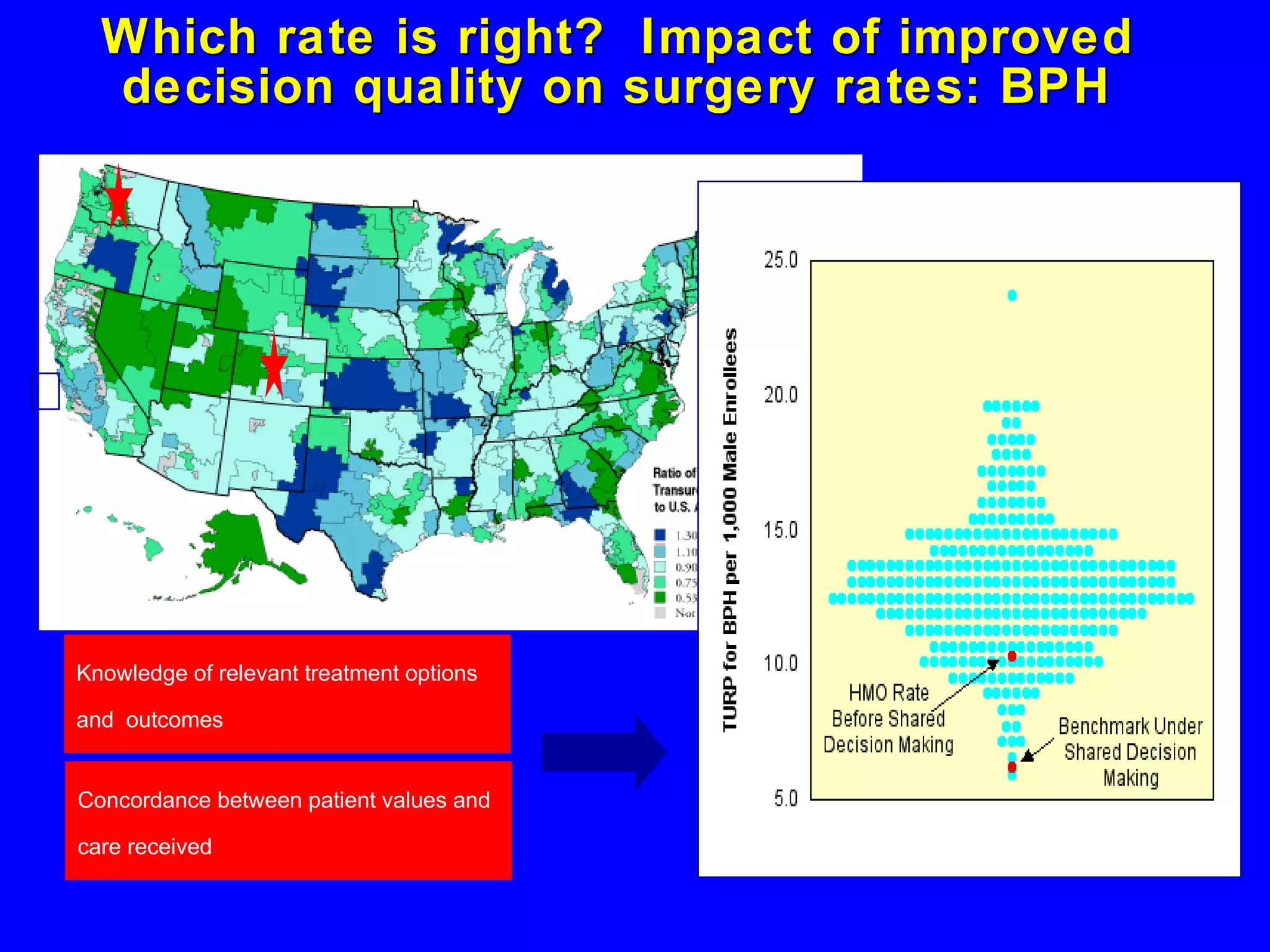

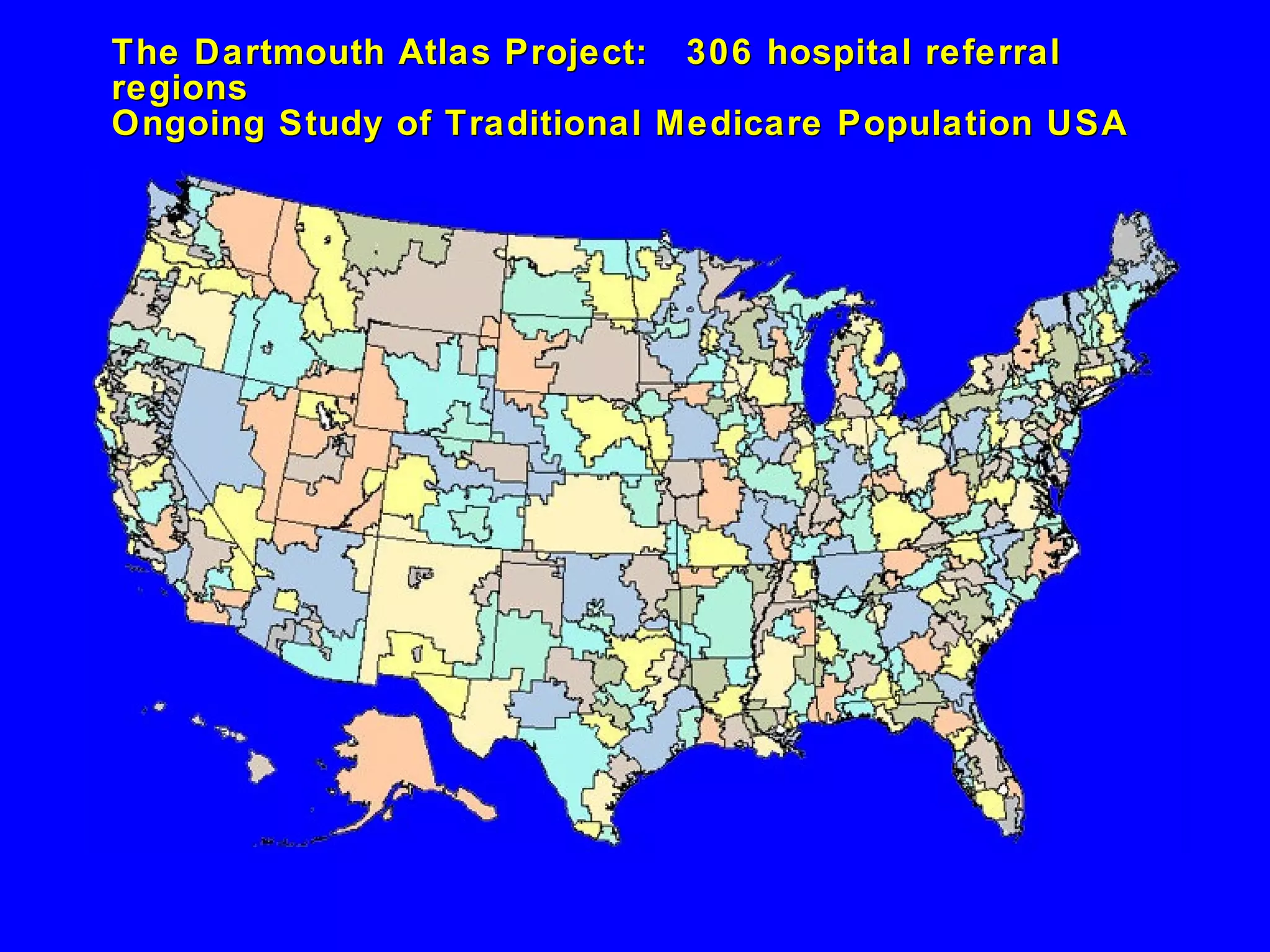

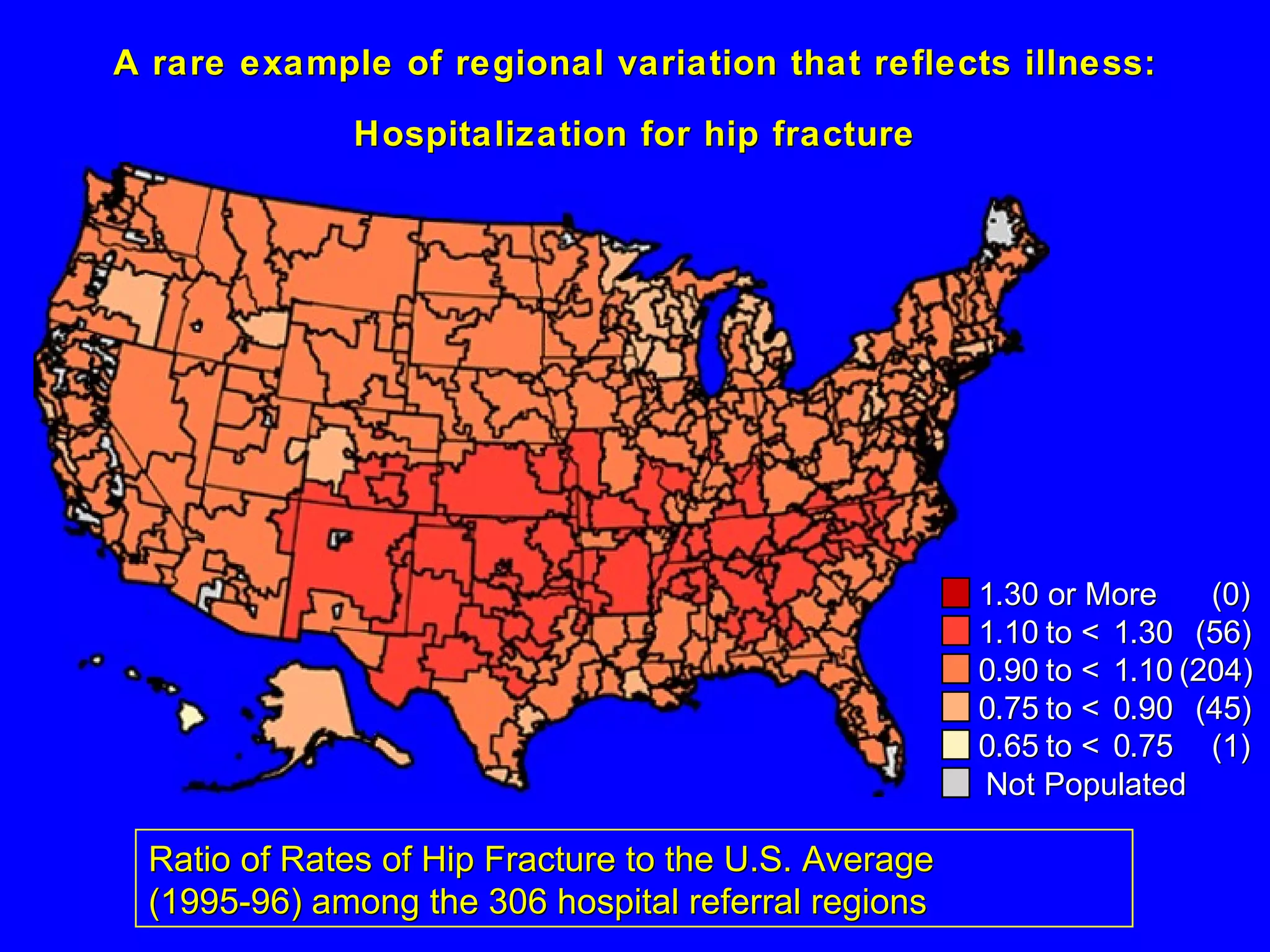

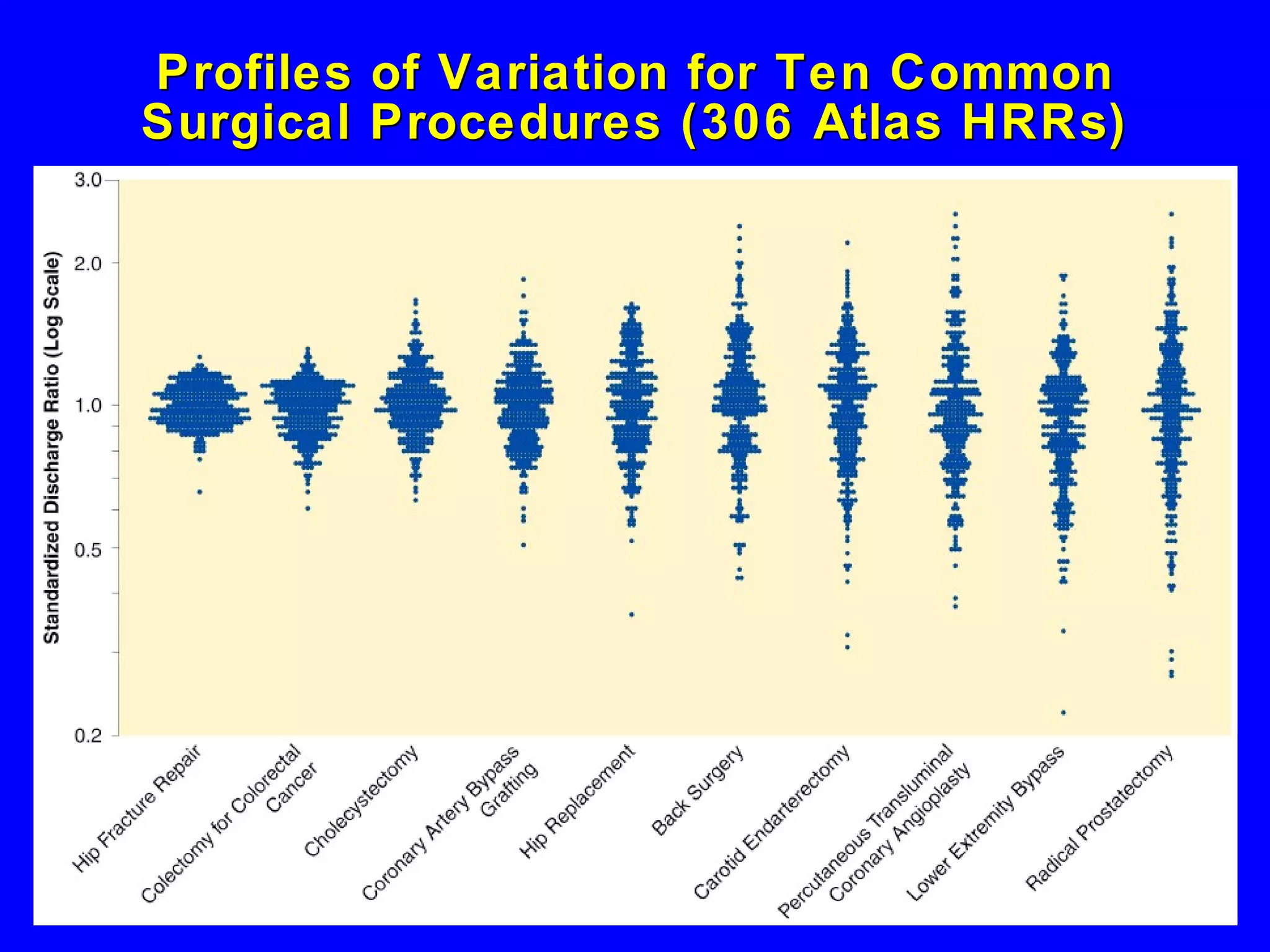

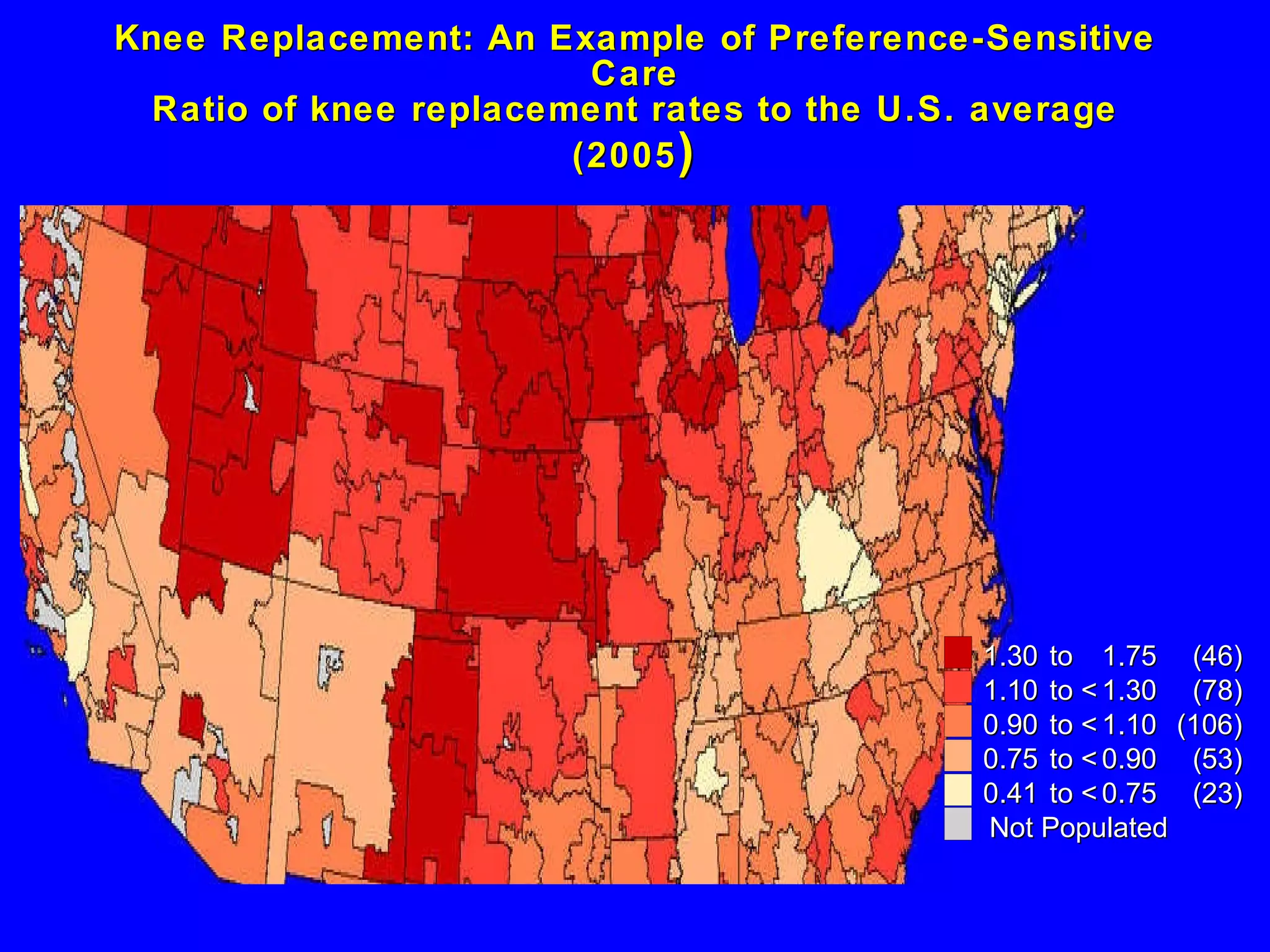

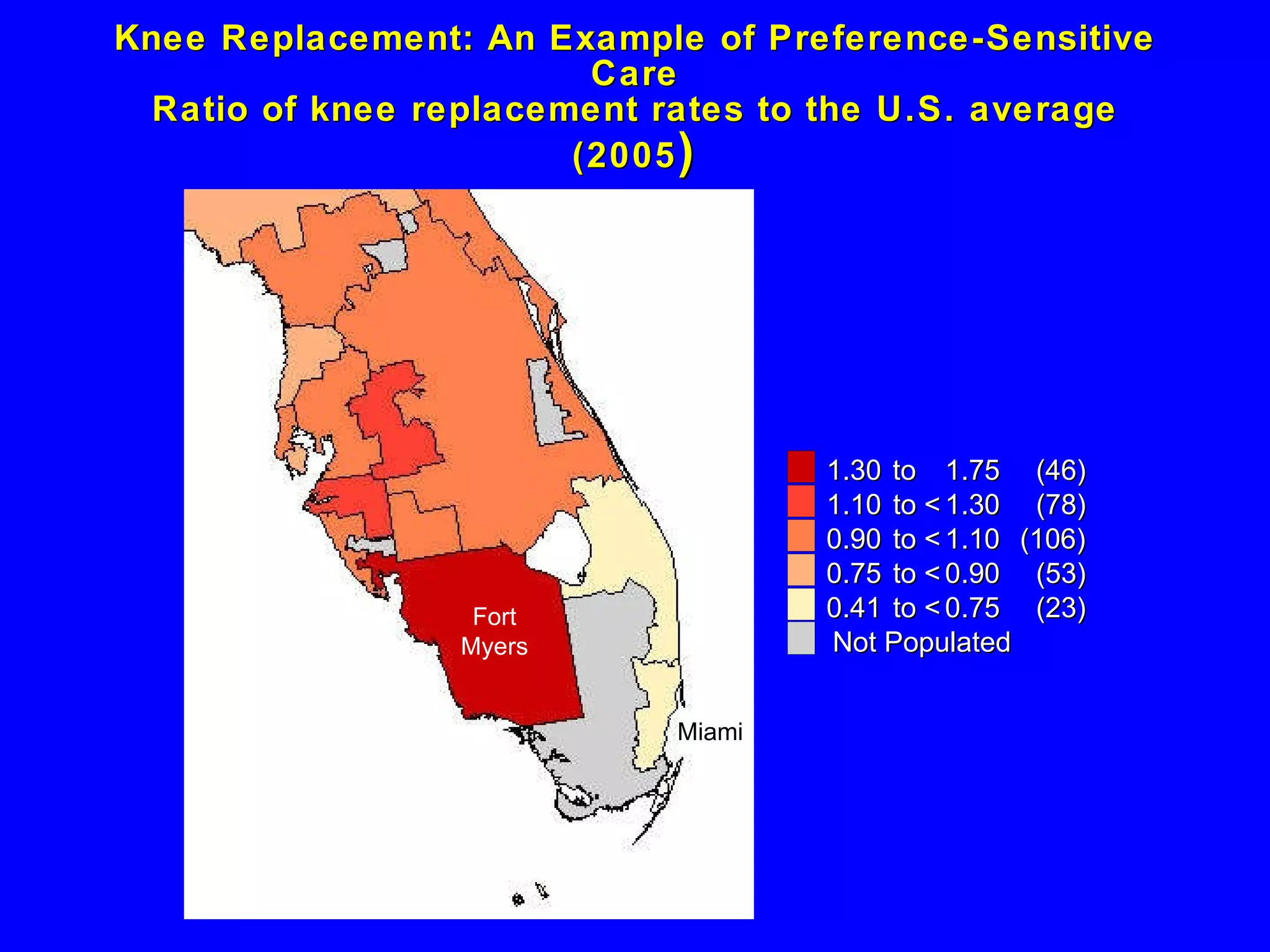

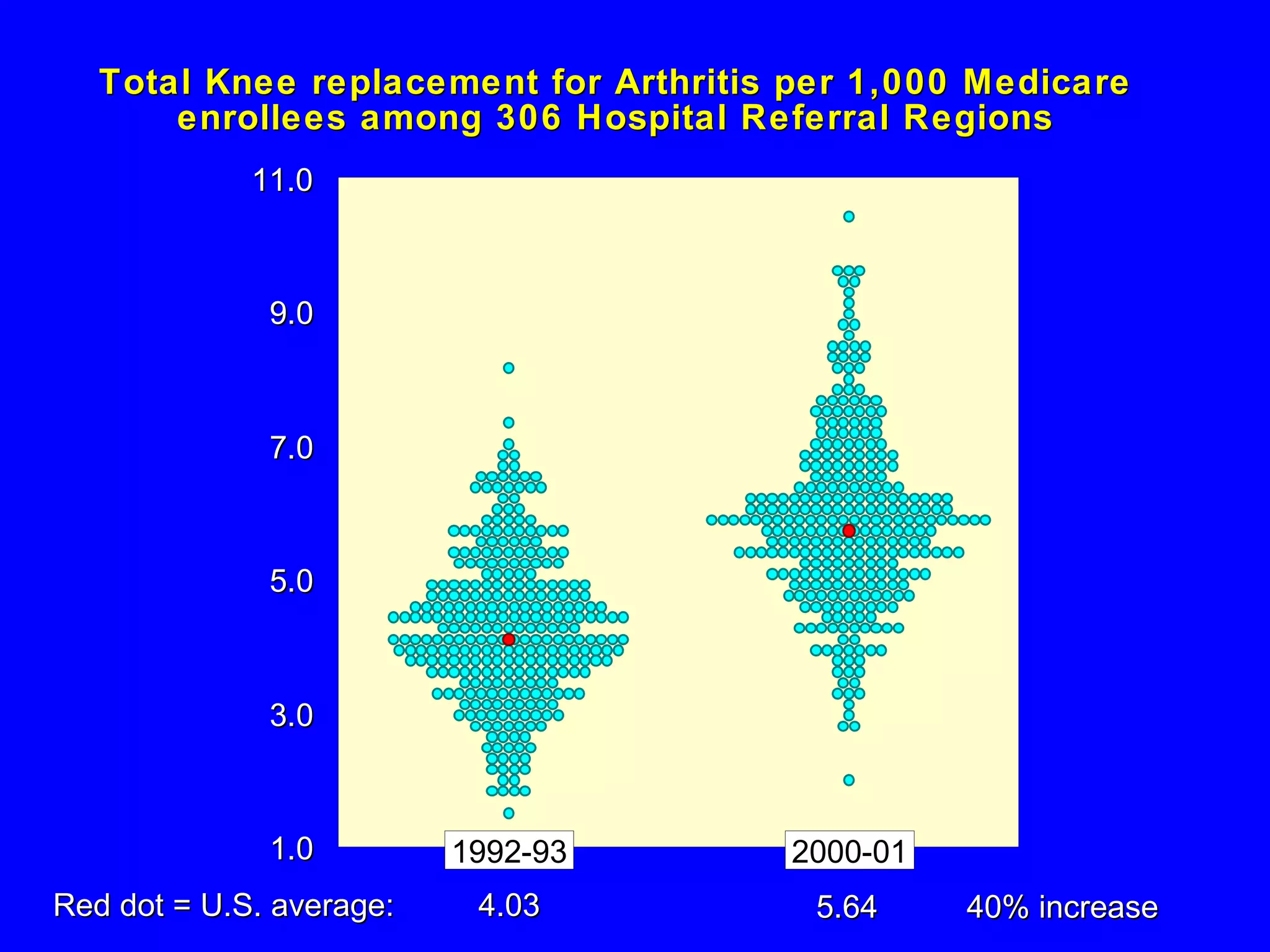

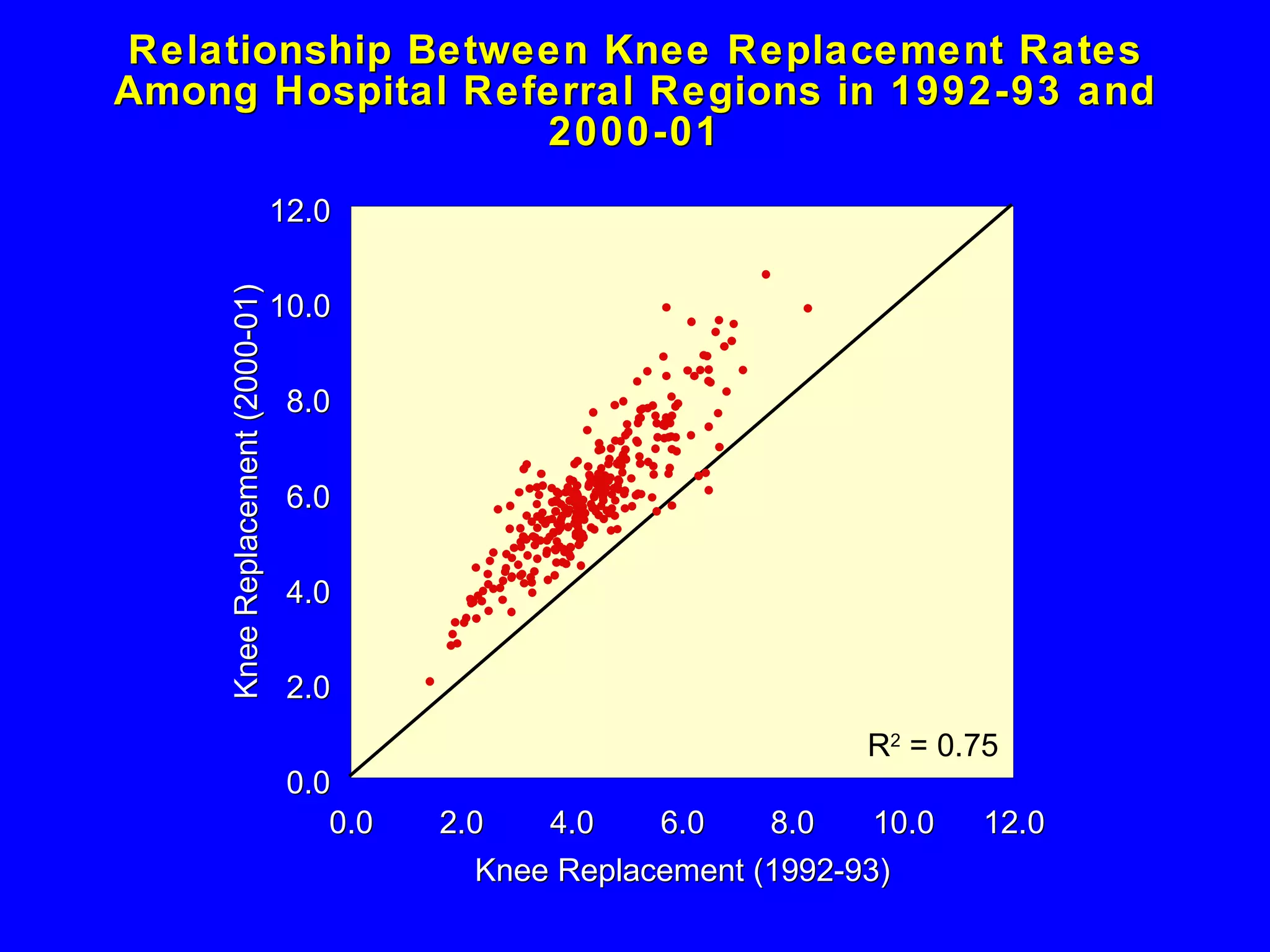

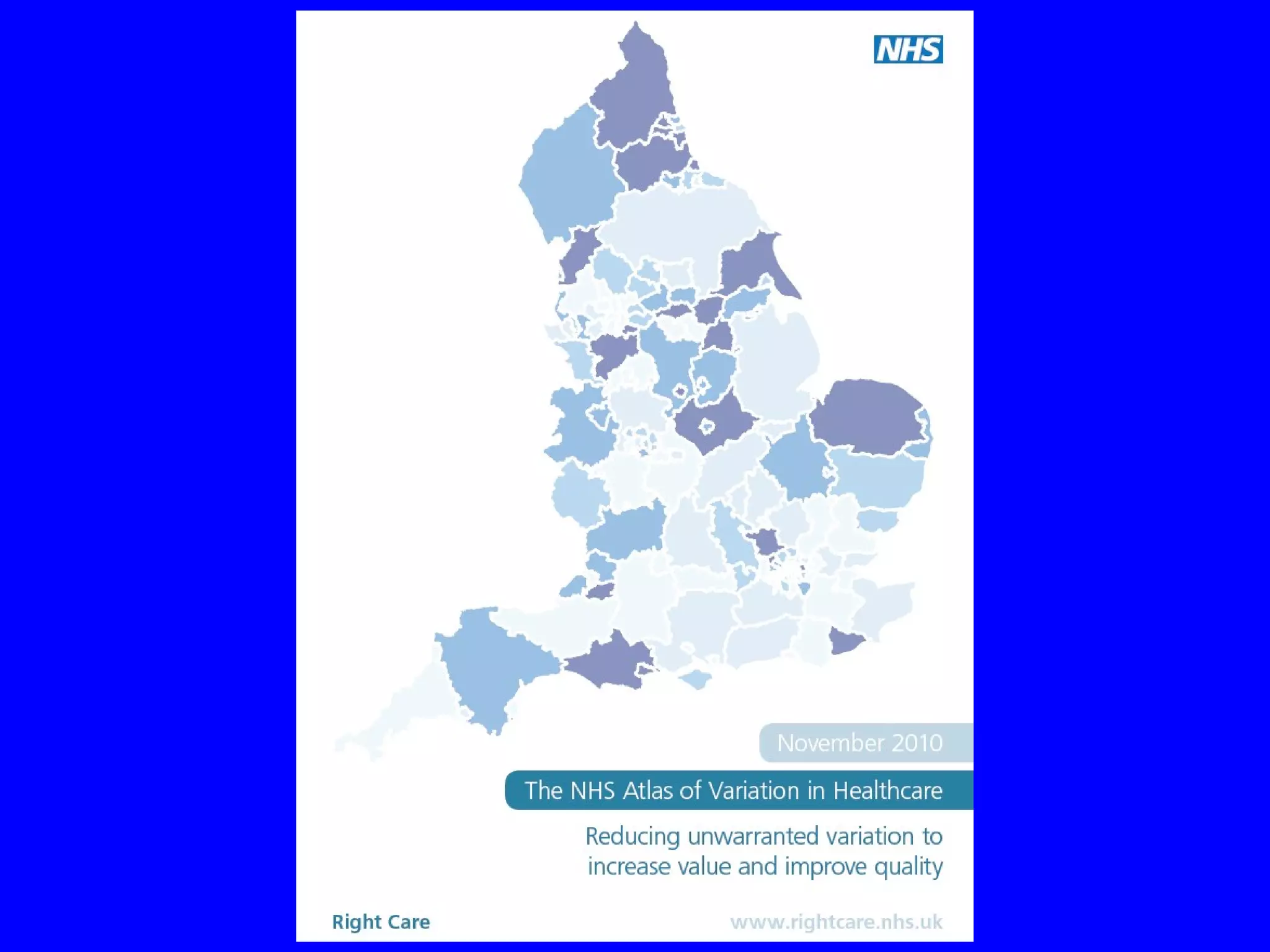

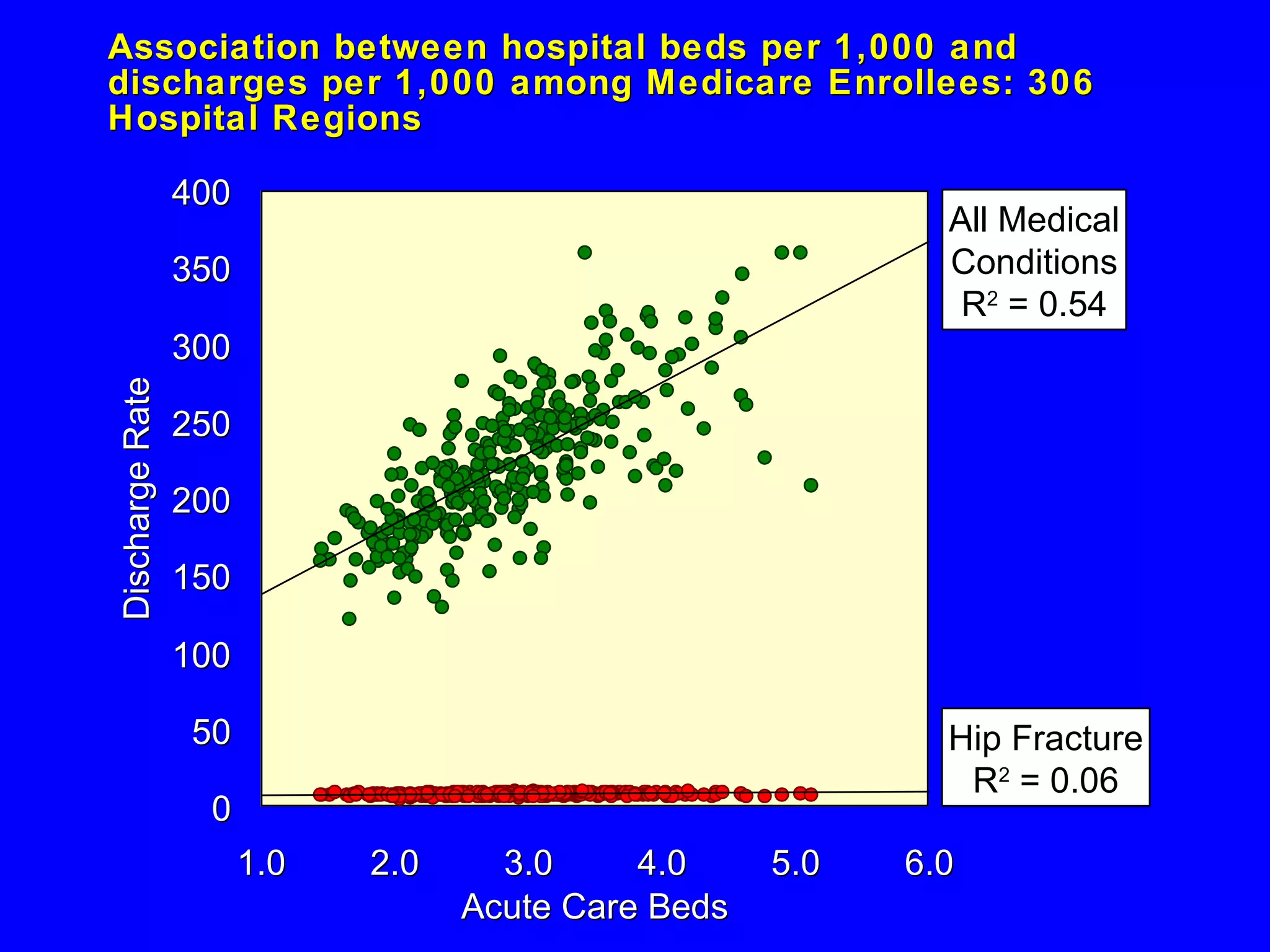

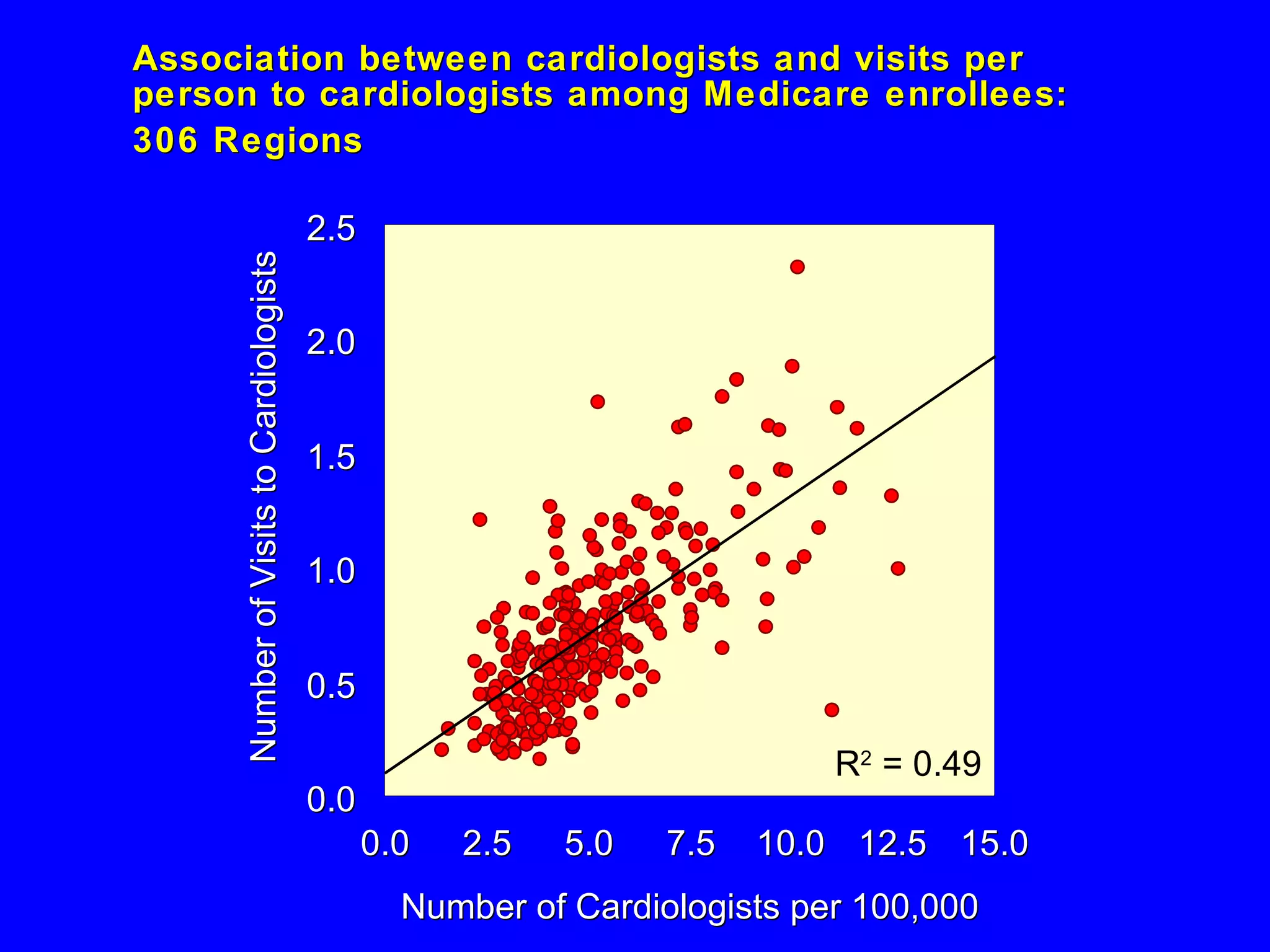

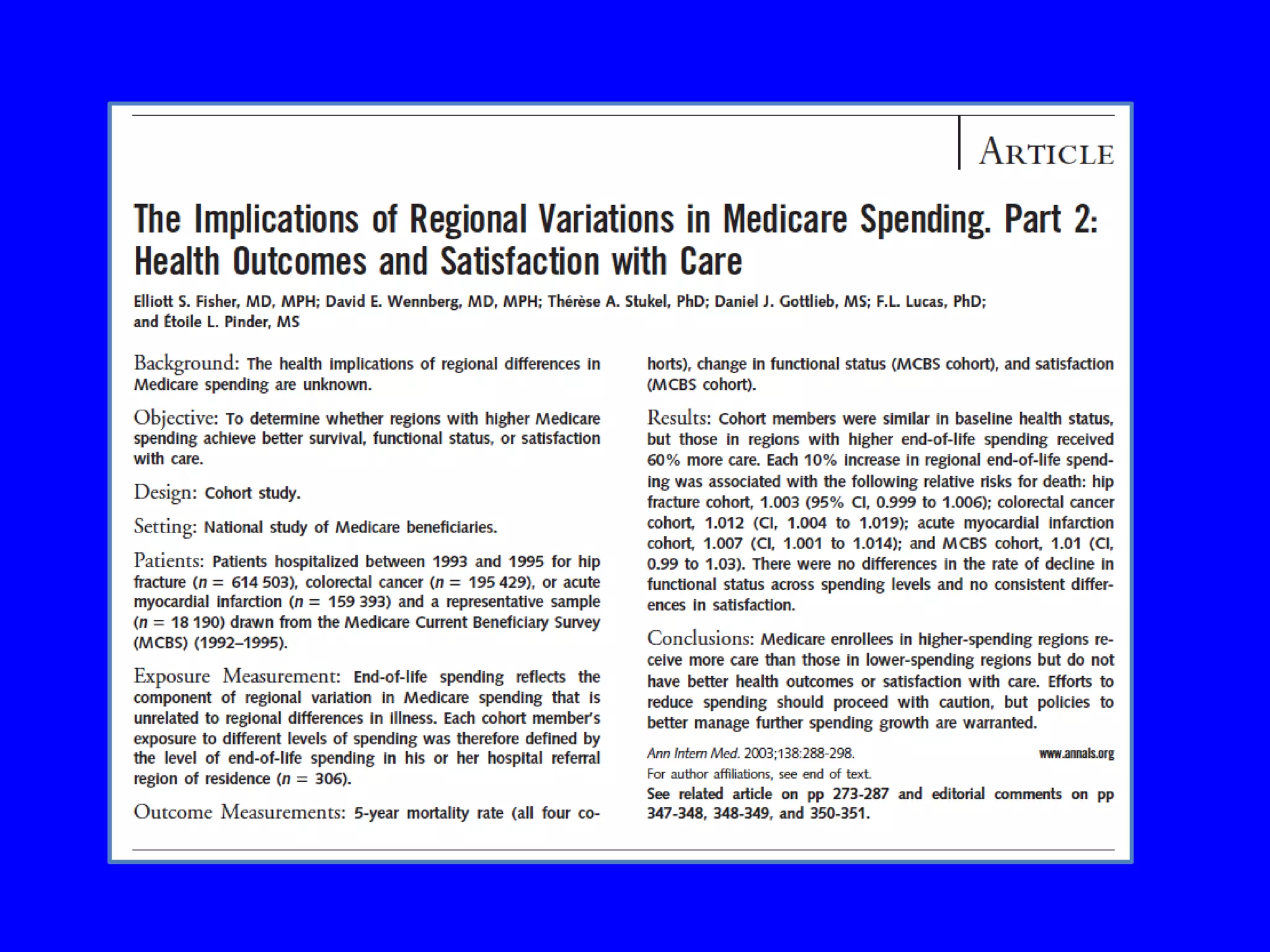

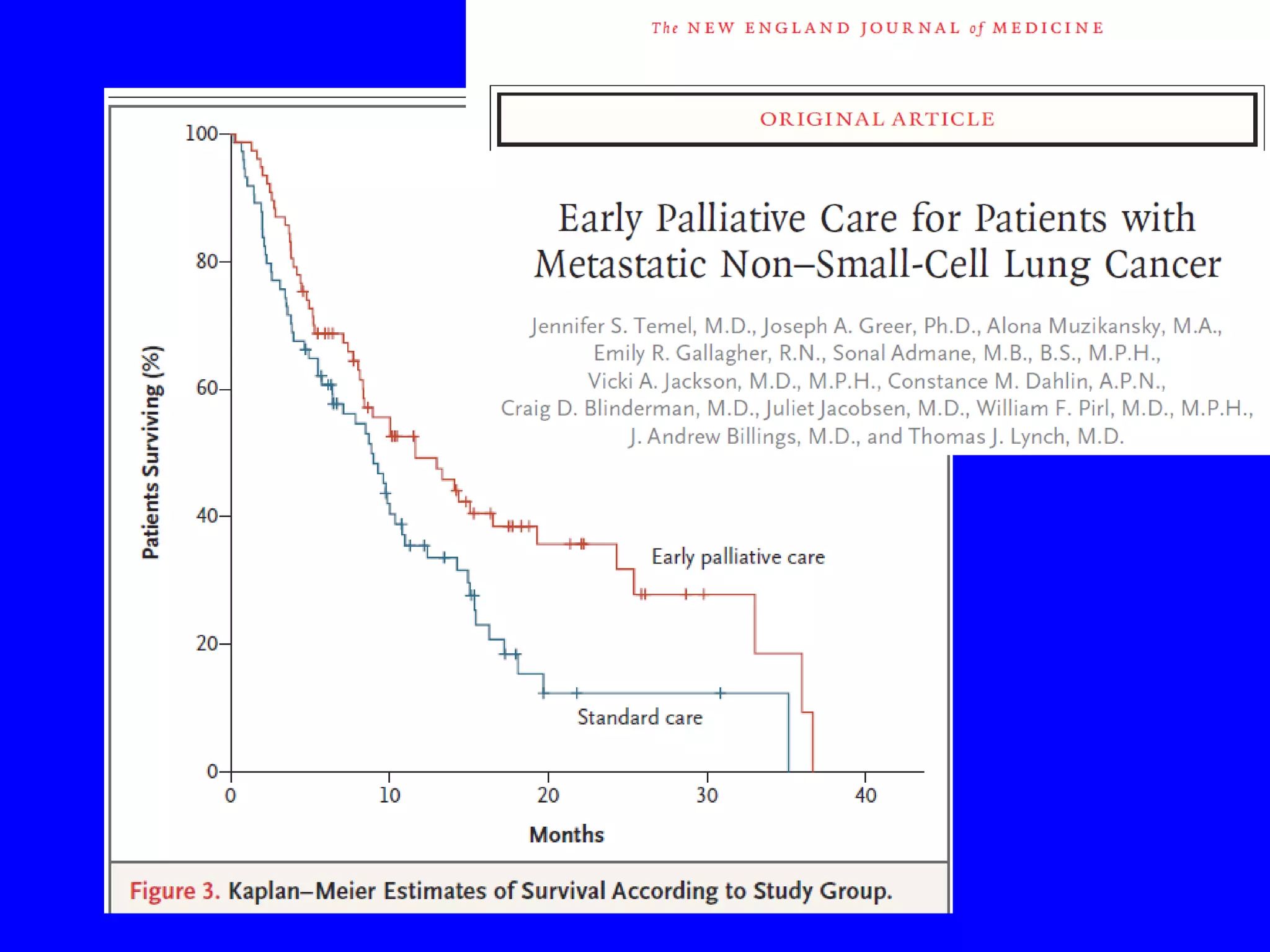

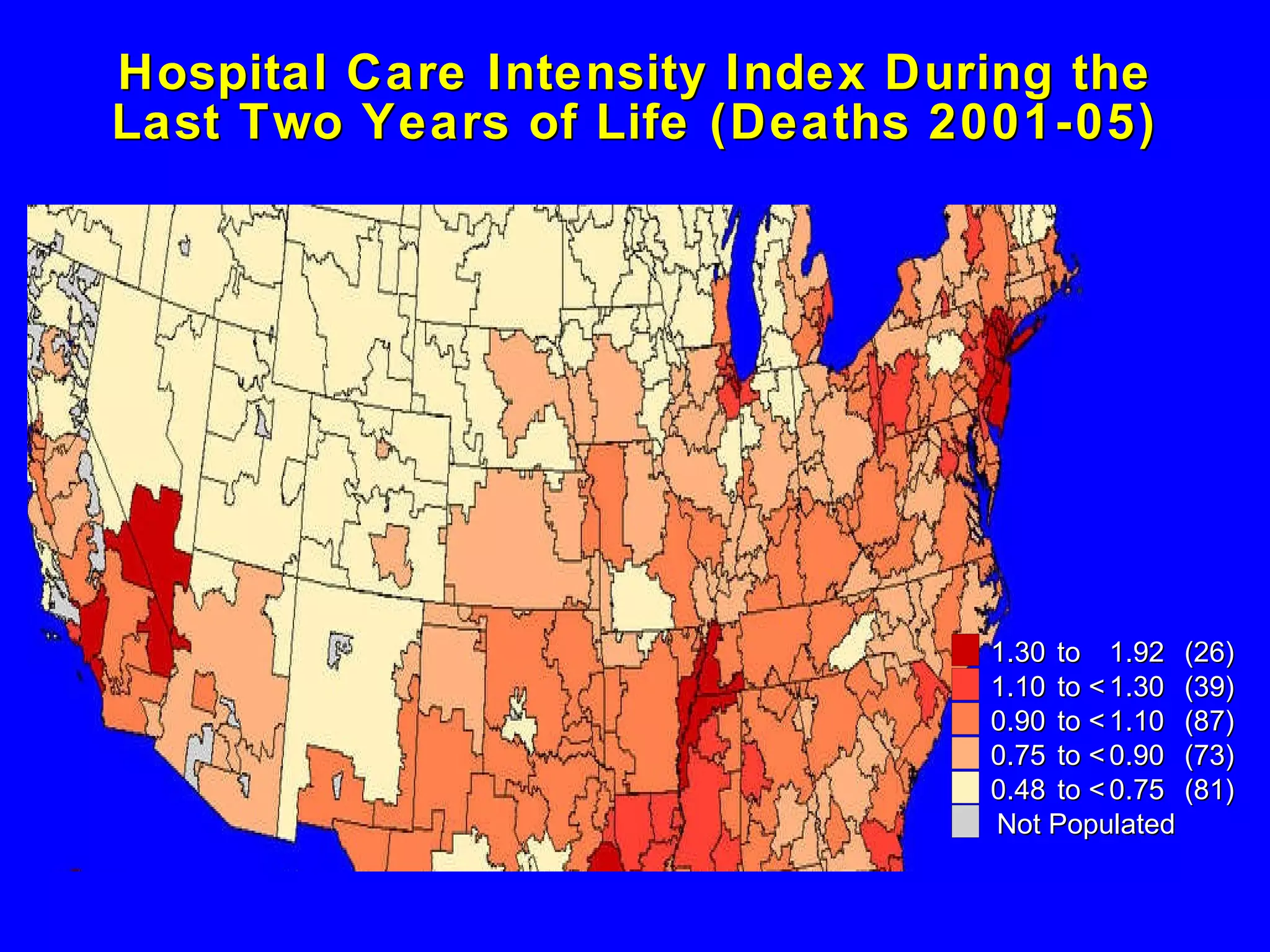

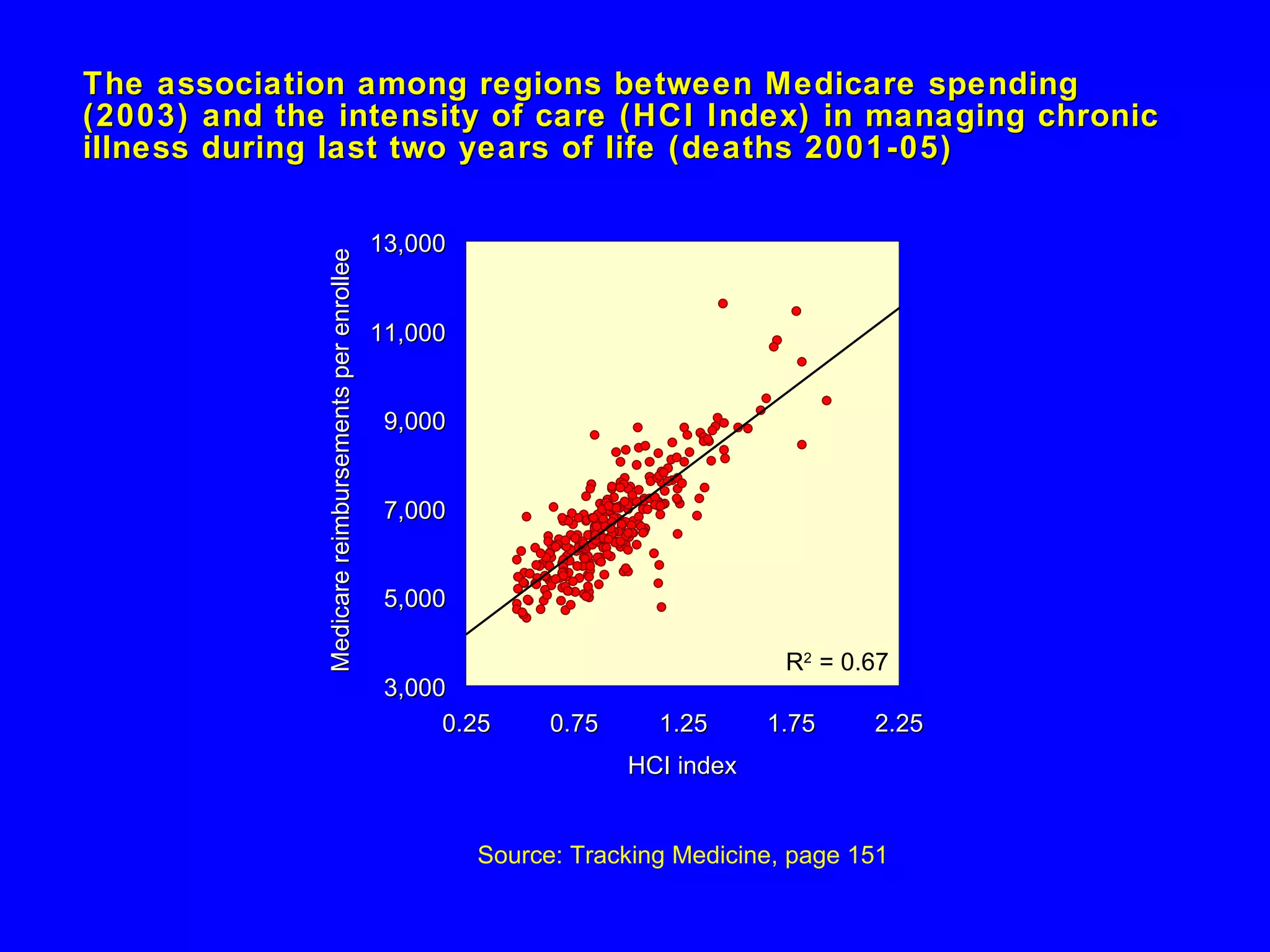

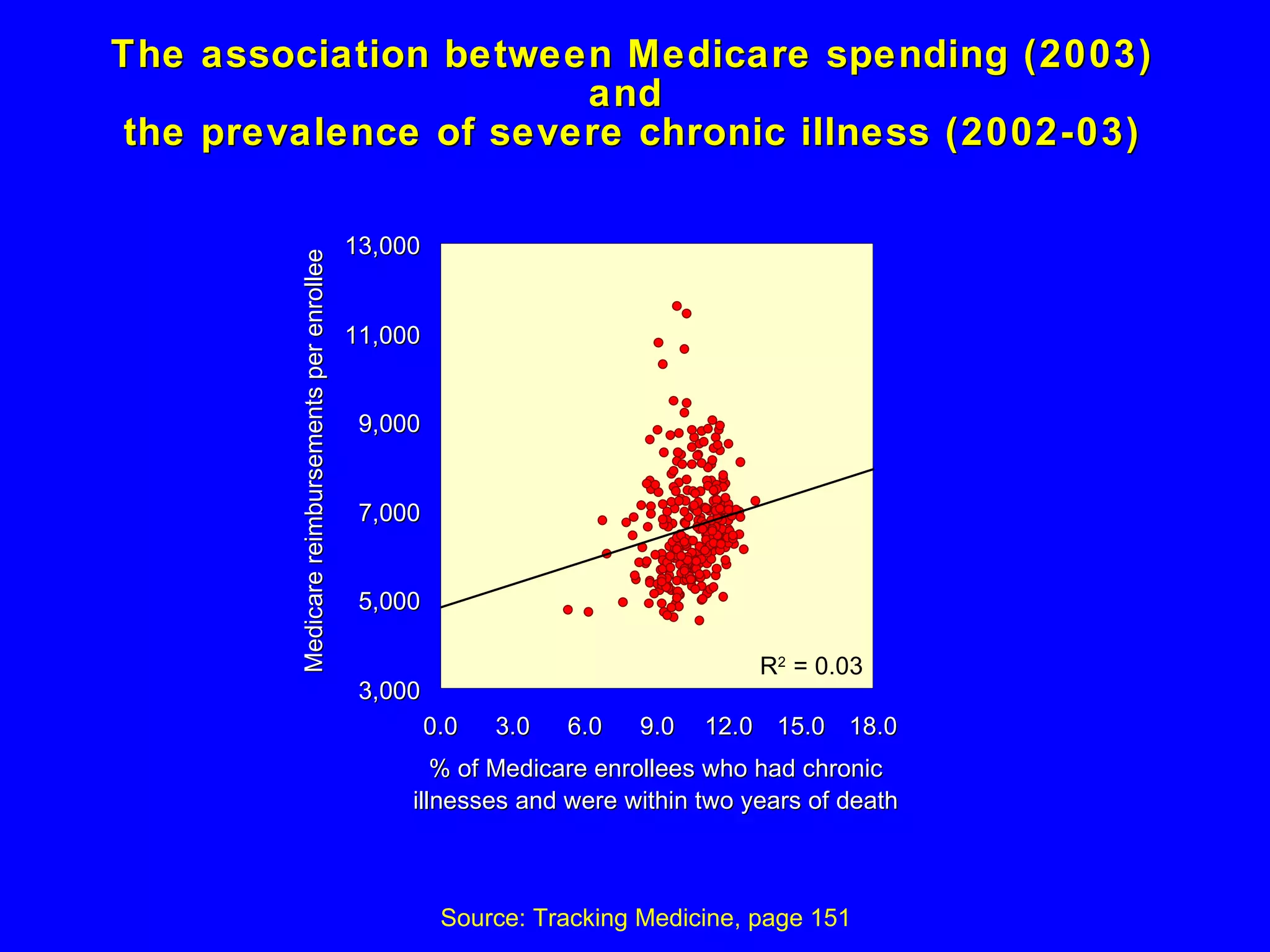

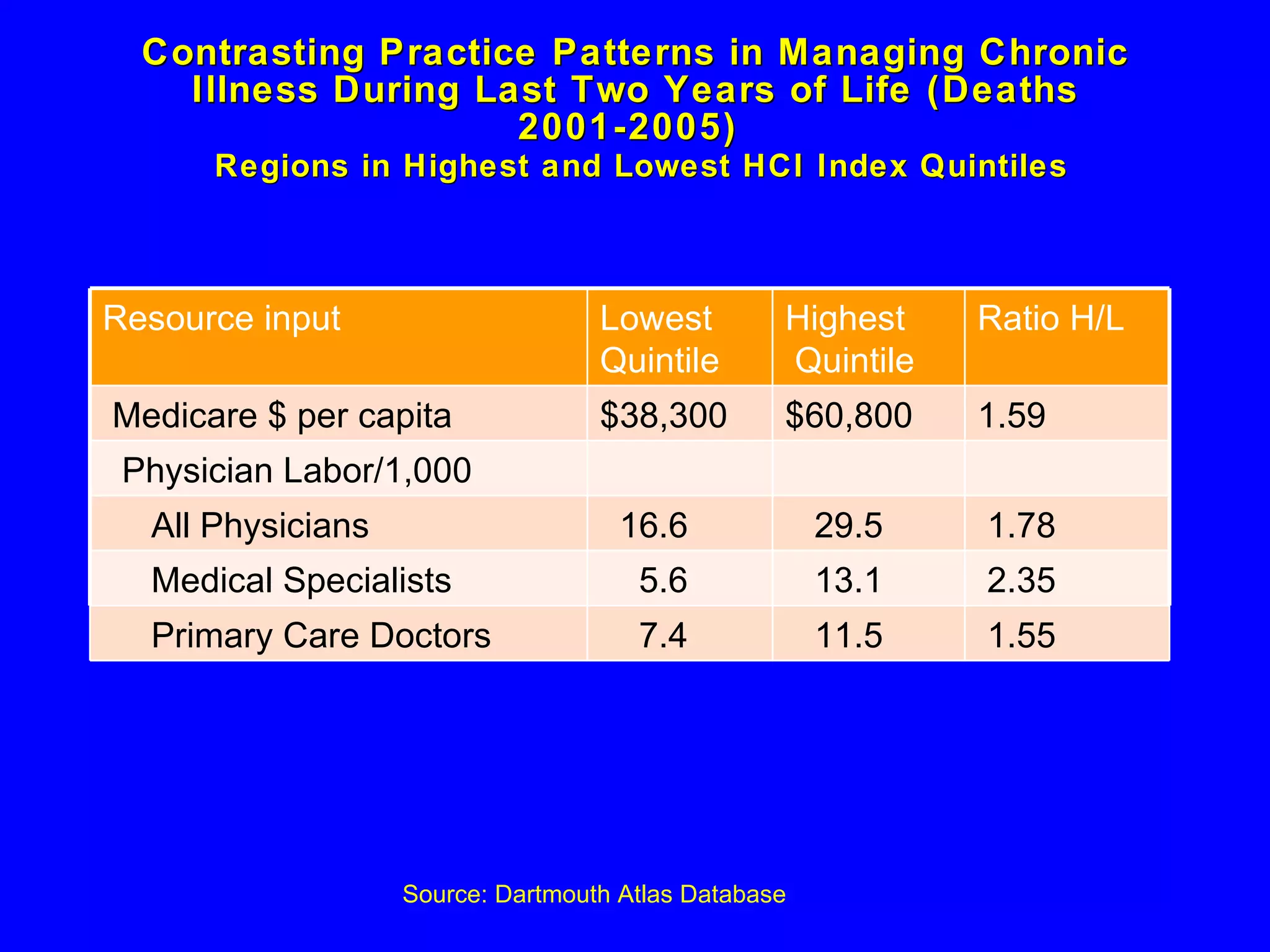

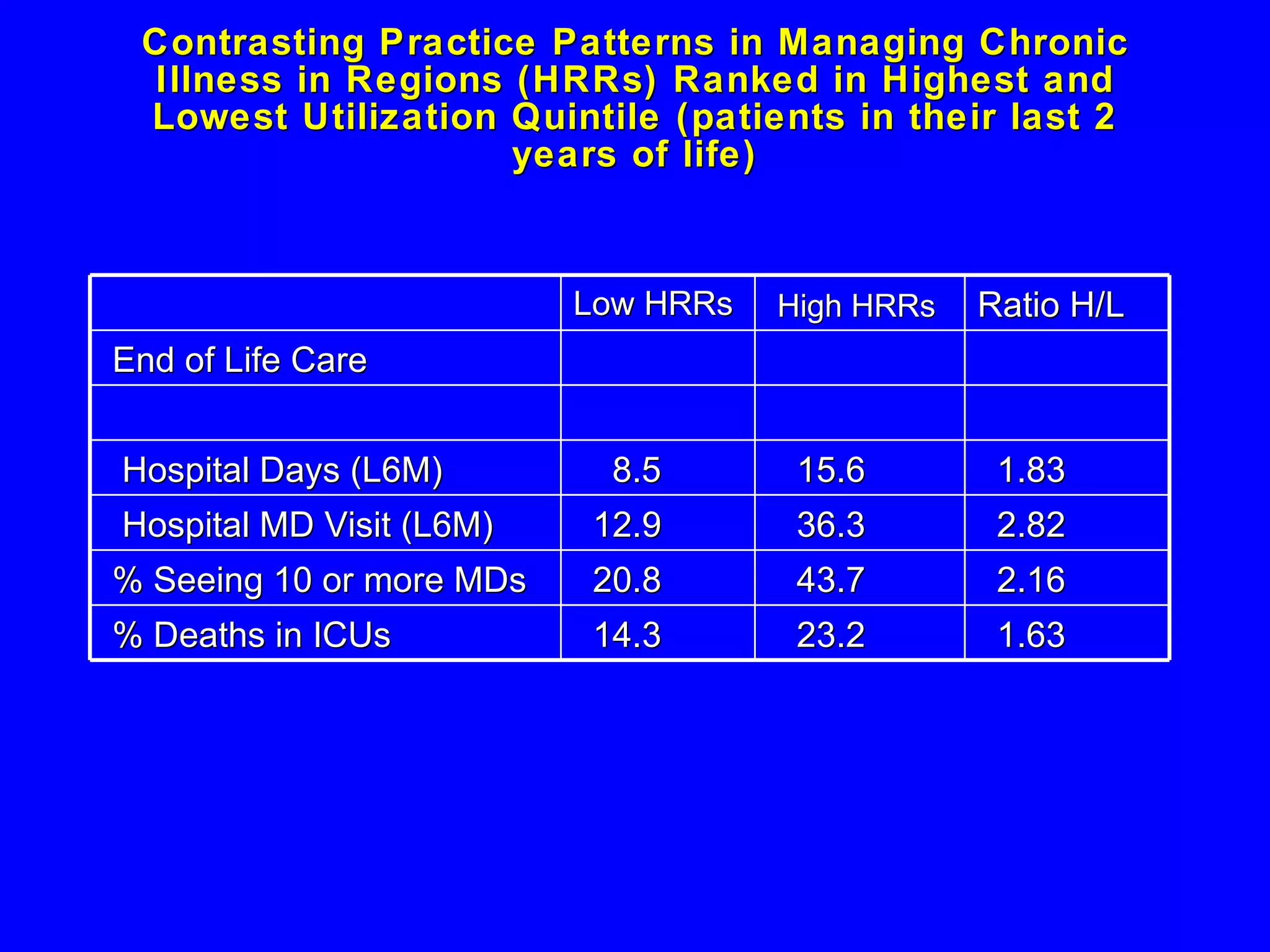

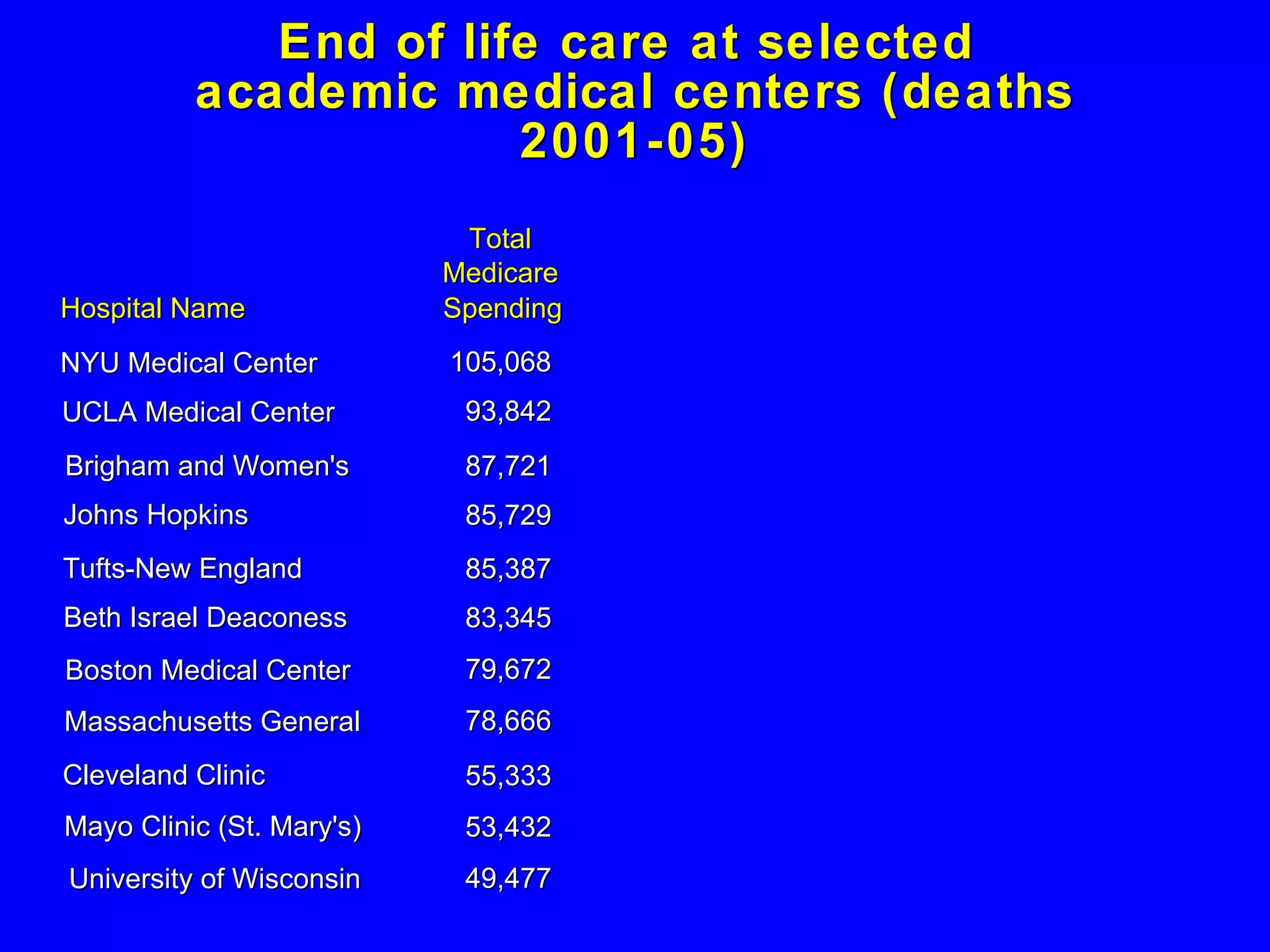

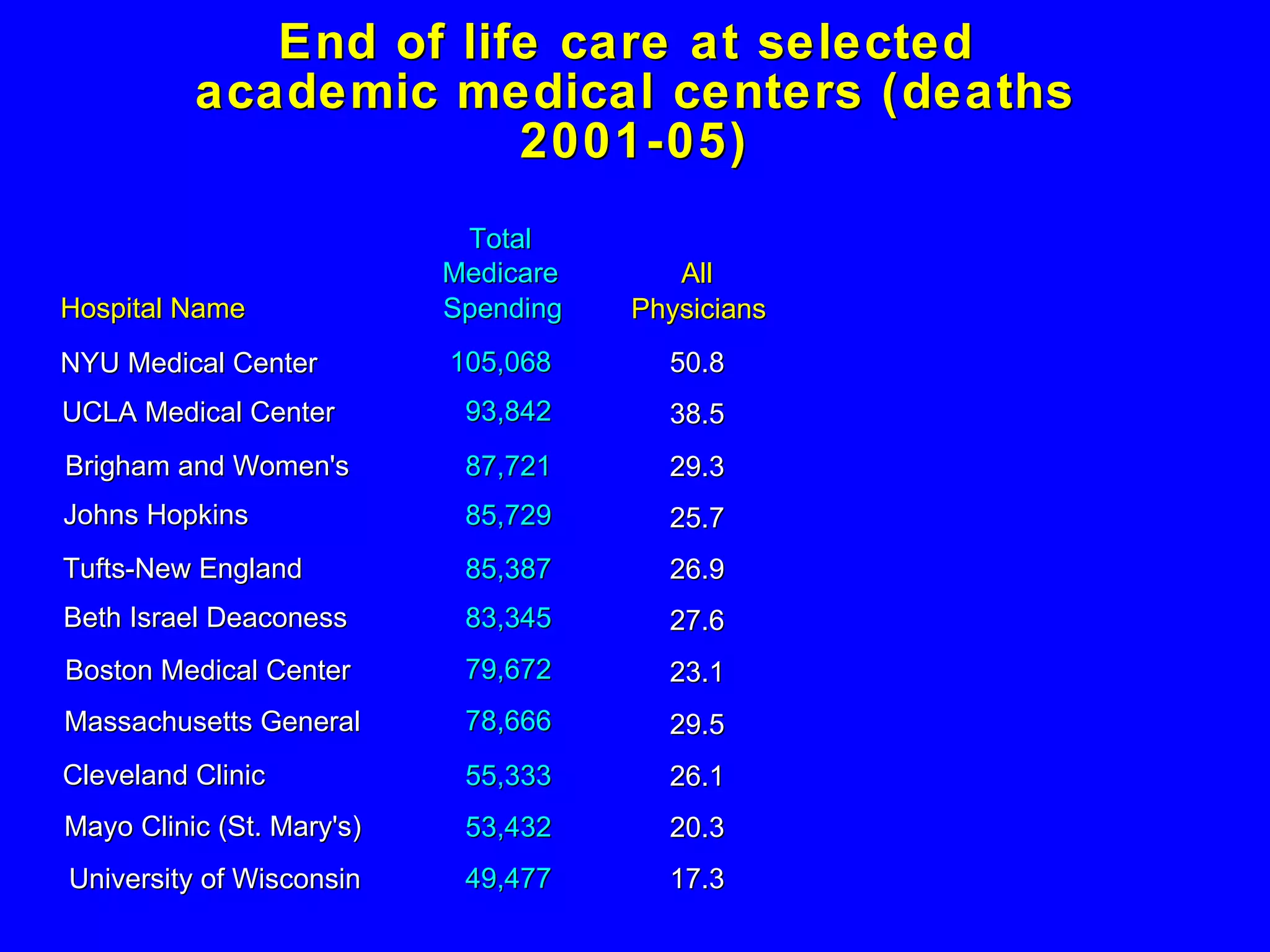

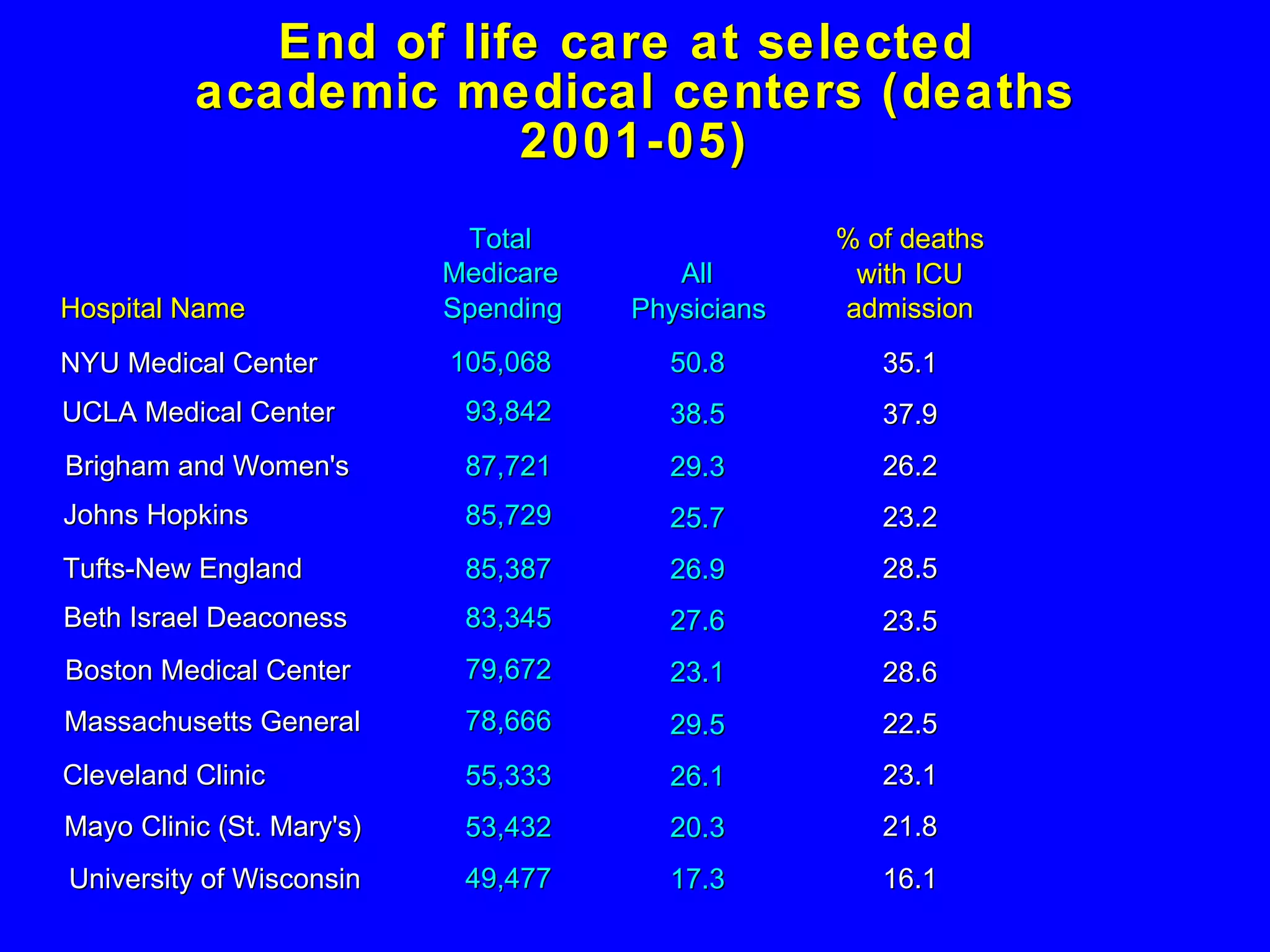

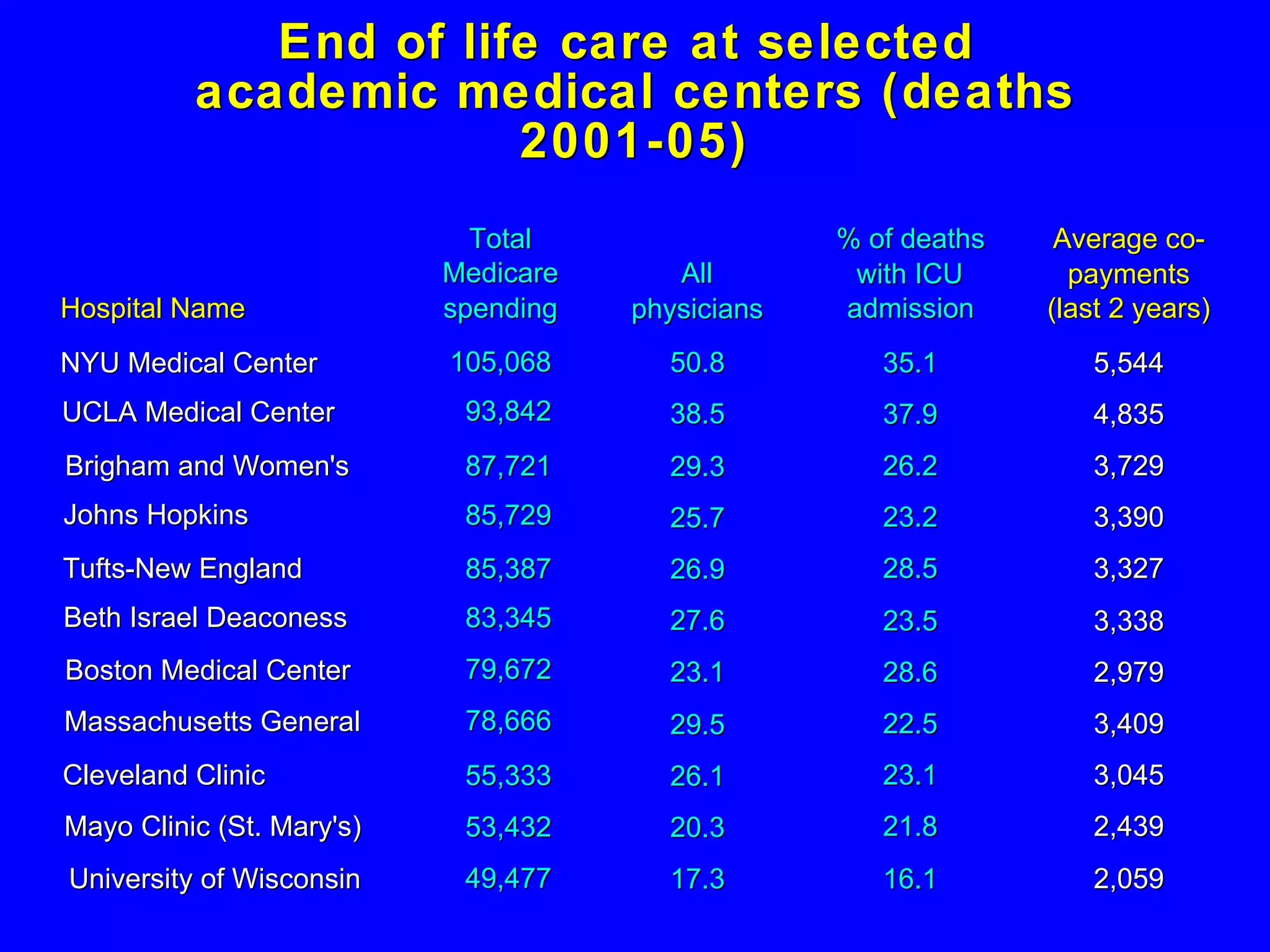

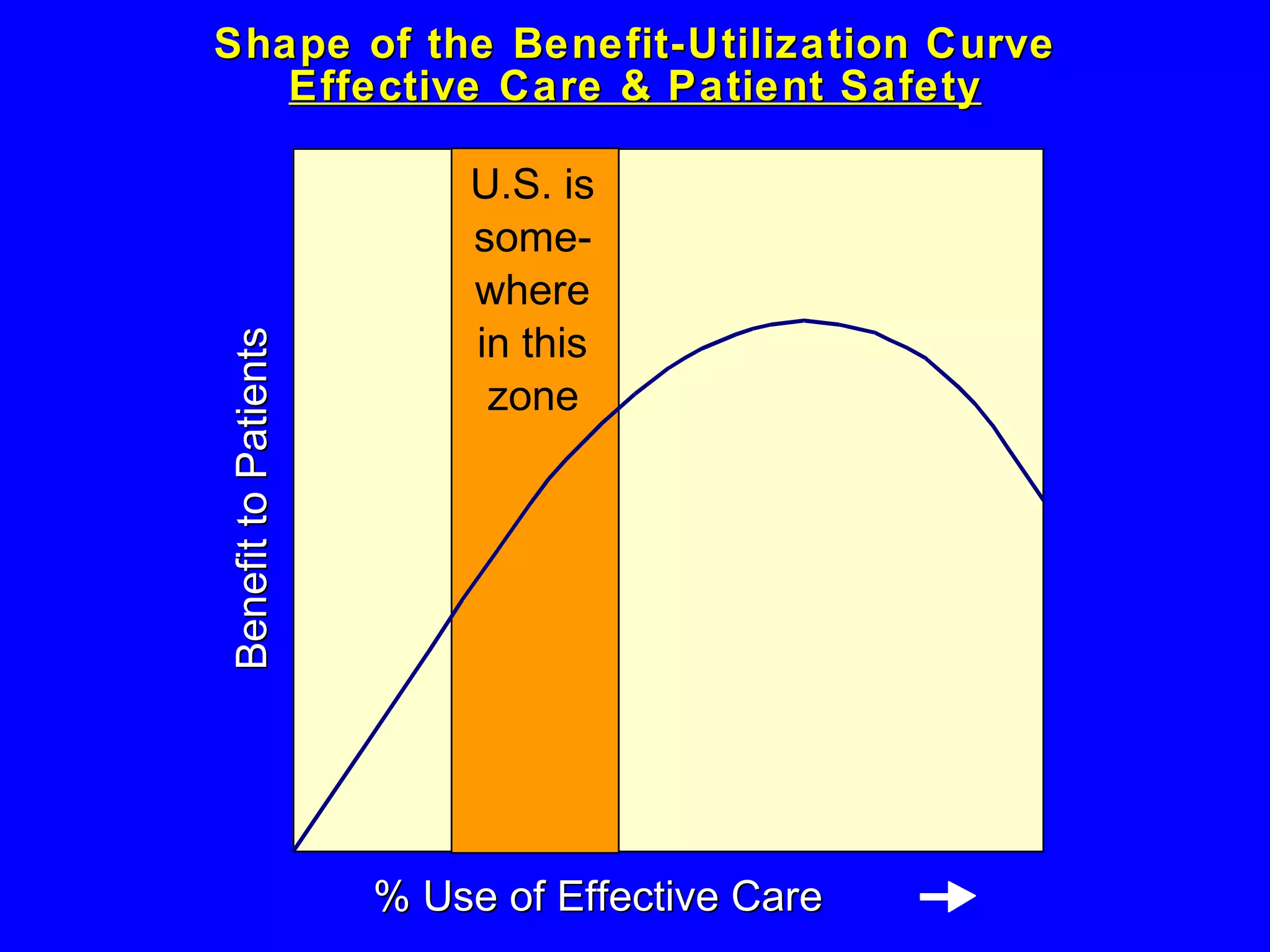

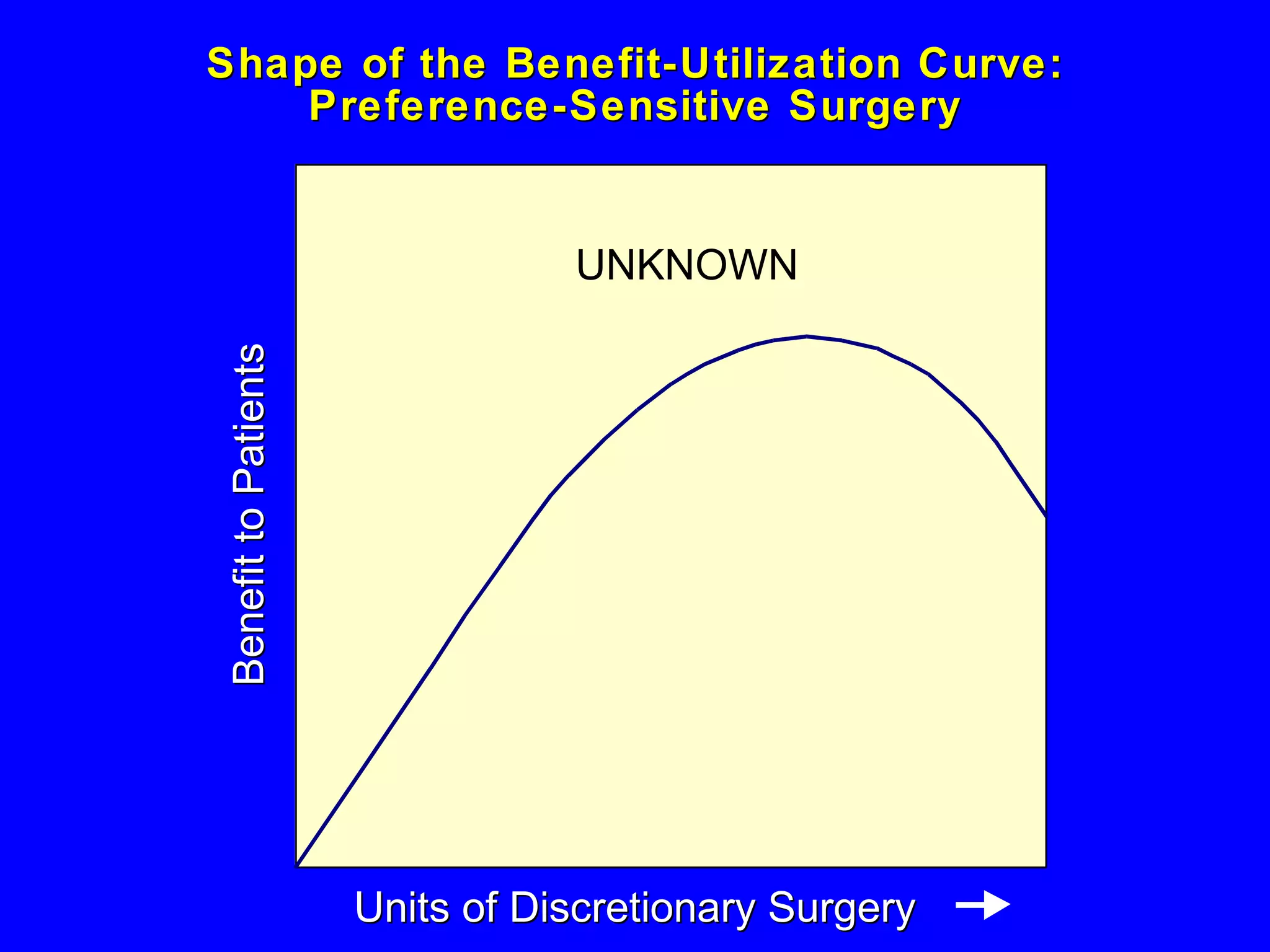

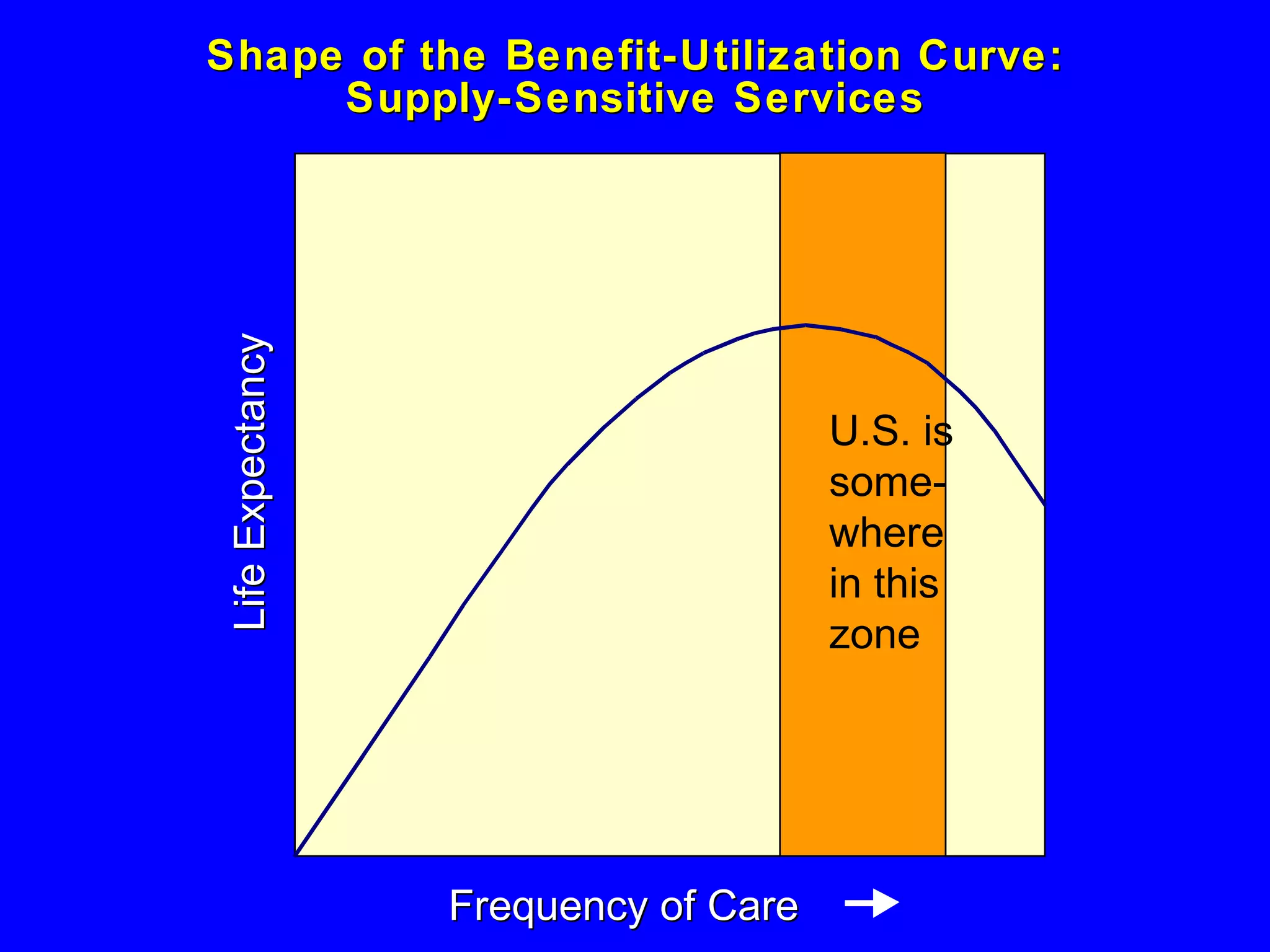

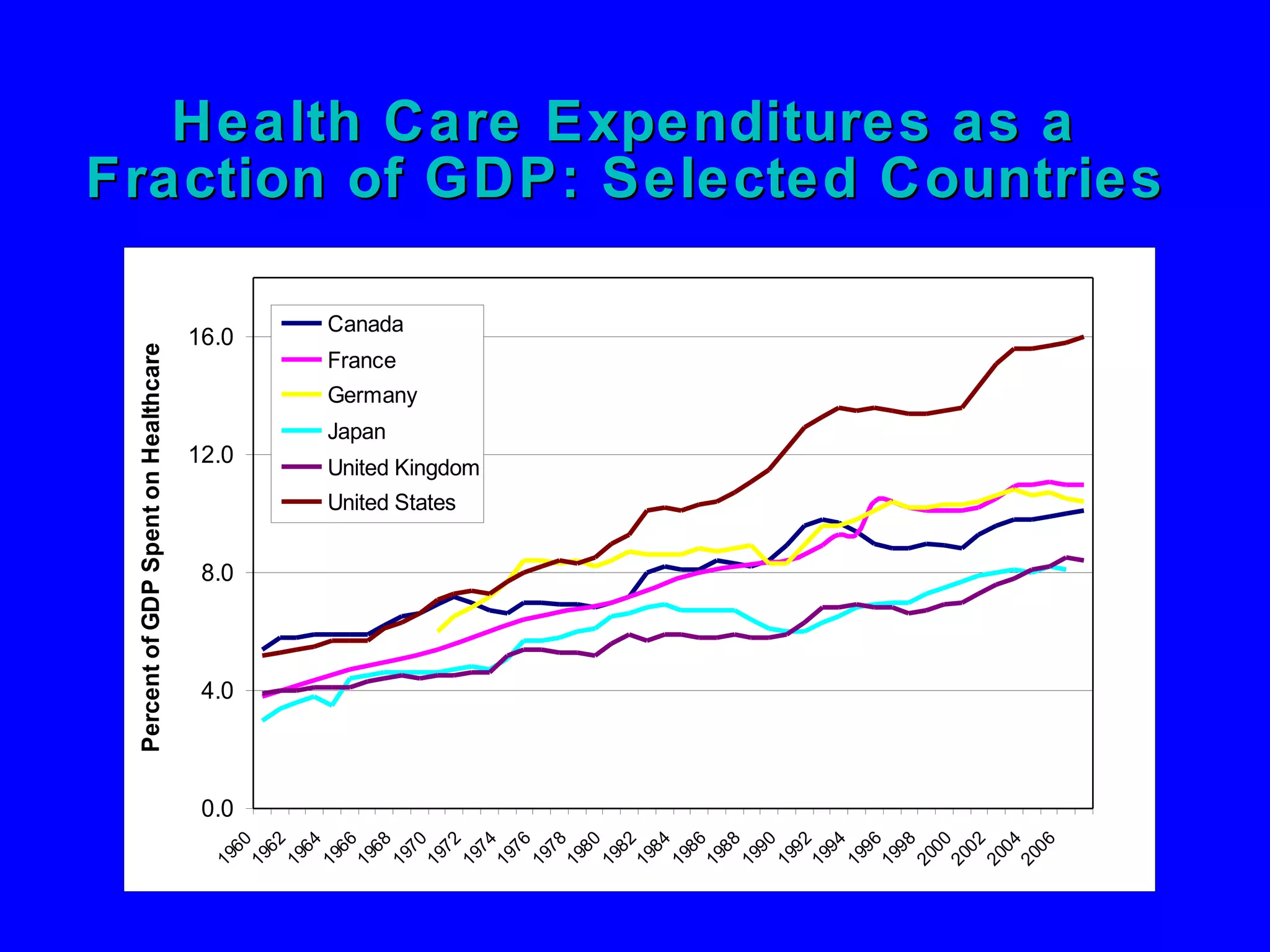

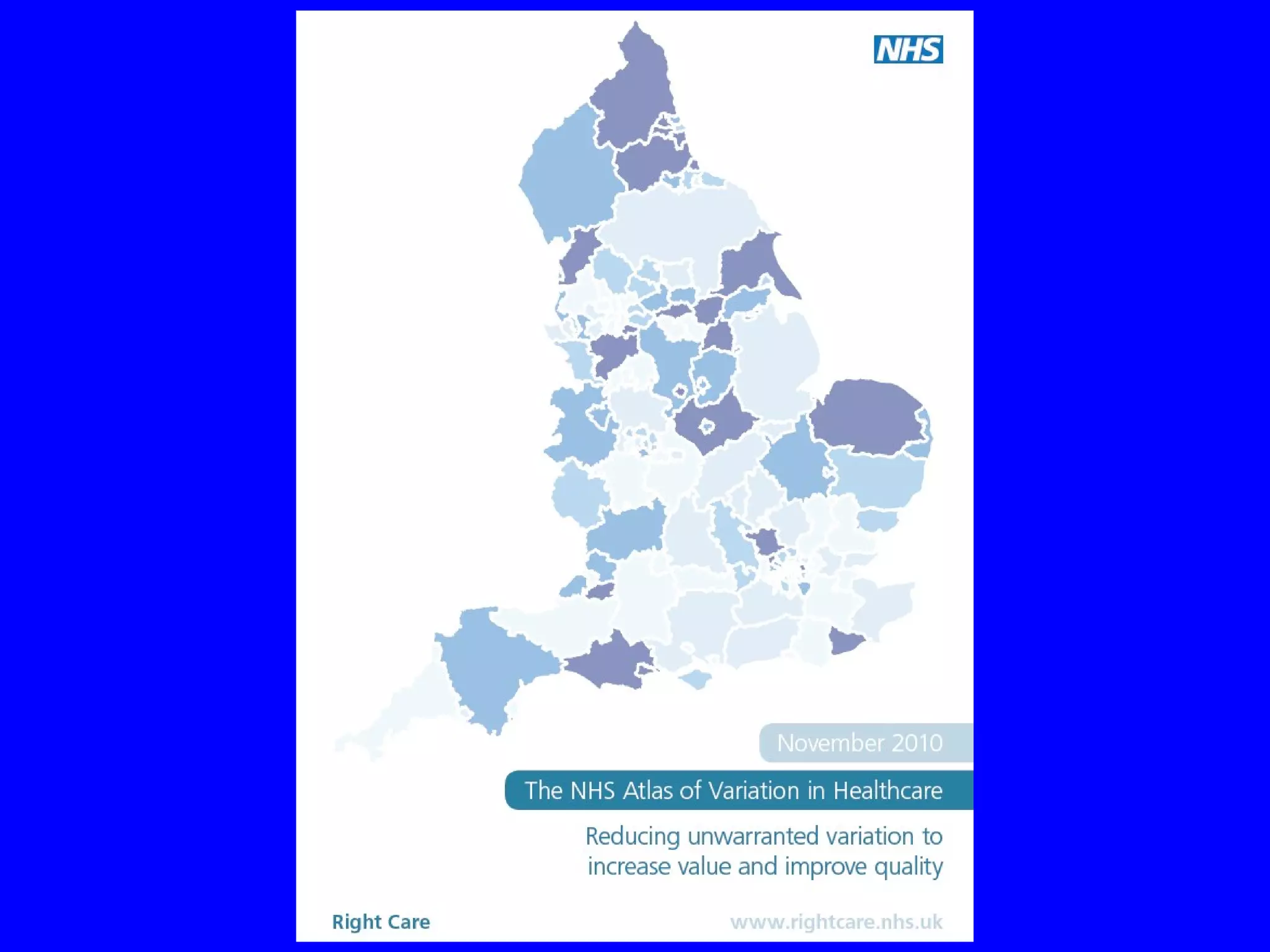

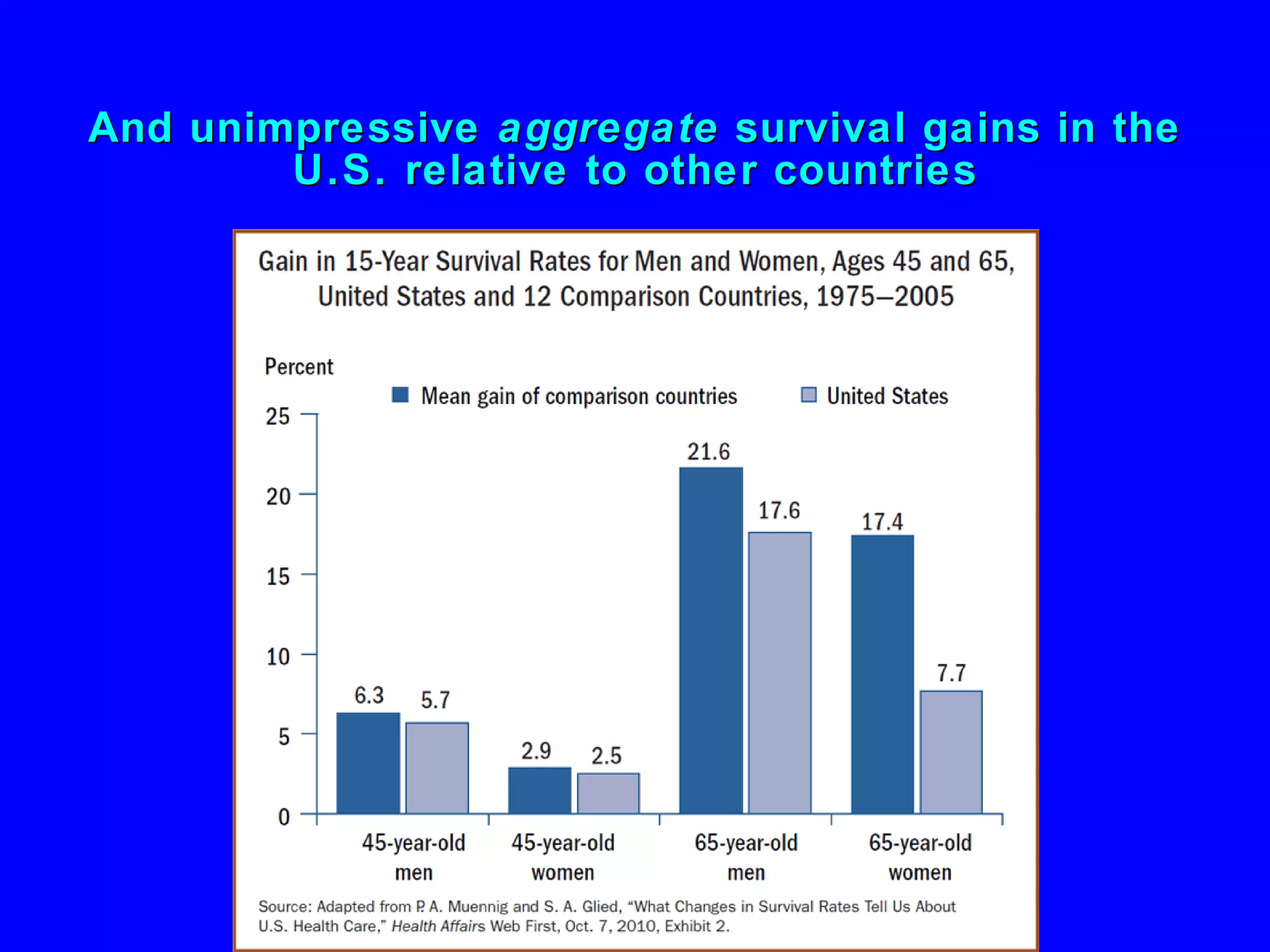

The document summarizes research on variations in medical practice and healthcare utilization in different geographic regions. It discusses studies in Vermont and Maine that found wide variations in tonsillectomy and hysterectomy rates that did not correlate with patient characteristics or health status. The Dartmouth Atlas Project also found significant unwarranted variations across hospital referral regions in procedures, spending, and end-of-life care intensity. Areas with more healthcare resources generally had higher utilization and spending but not better outcomes.