Dissonance and Discomfort Does a Simple Cognitive Inconsisten

- 1. Dissonance and Discomfort: Does a Simple Cognitive Inconsistency Evoke a Negative Affective State? Nicholas Levy, Cindy Harmon-Jones, and Eddie Harmon-Jones The University of New South Wales Festinger (1957) described cognitive dissonance as psychological discomfort that resulted from a cognitive inconsistency. Discussion of dissonance for the past 60 years has focused on the classic paradigms and the motivation to reduce dissonance, but some have noted that this represents a narrow application of Festinger’s ideas (Gawronski & Brannon, in press). Recent research has suggested, but not demonstrated, that simple cognitive inconsistencies may also evoke the affective and motivational state of dissonance (e.g., E. Harmon-Jones, Harmon-Jones, & Levy, 2015). In the current experiments, participants read sentences that ended with incongruent or congruent final words. In Study 1, sentences with incongruent endings led to more negative implicit affect than did sentences with congruent endings. Study 2 replicated this finding, with the addition of self-report and facial electromyography. These findings indicate that simple inconsistencies can evoke dissonance. Keywords: dissonance, consistency, emotion processing,

- 2. implicit measures, affect Festinger’s (1957) cognitive dissonance the- ory revolutionized the understanding of the re- lationships between cognitive, motivational, and affective processes. According to the orig- inal theory, “In the presence of an inconsistency there is psychological discomfort” (Festinger, 1957, p. 2). Inconsistency here refers to “non- fitting relations between cognitions” (Festinger, 1957, p. 3). Festinger, (1957) speculated that If a person were standing in the rain and yet could see no evidence that he was getting wet, these two cogni- tions would be dissonant with one another because he knows from experience that getting wet follows from being out in the rain. (p. 14) It is interesting to note that Festinger did not distinguish between dissonance as a relation between cognitions and dissonance as a moti- vational state of discomfort: “nonfitting rela- tions among cognitions [are] a motivating factor in [their] own right.” (Festinger, 1957, p. 3). In this light, Festinger’s example suggests even simple inconsistencies would cause dissonance discomfort. Although this theory and evidence (see below) suggest that a simple cognitive in- consistency should evoke psychological dis- comfort, no prior research has tested this di- rectly. Thus, the current research examined whether a simple cognitive inconsistency could evoke the psychological discomfort of disso- nance.

- 3. Models of affect recognize that affective states are characterized by psychophysiological dimensions (e.g., Bradley, Greenwald, Petry, & Lang, 1992; Russell, 1980), including, but not limited to, affective valence (how pleasant or unpleasant an affective state is; E. Harmon- Jones, Harmon-Jones, Amodio, & Gable, 2011) and arousal (Gable & Harmon-Jones, 2013). The present studies measured both affective valence (Studies 1 and 2) and arousal (Study 2), because dissonance discomfort is characterized by both negative valence (Festinger, 1957) and arousal (Gerard, 1967; for review, see E. Harmon-Jones, 2000b). Cognitive Dissonance and Affect The first examination of cognitive dissonance theory observed dissonance after a violation of This article was published Online First September 28, 2017. Nicholas Levy, Cindy Harmon-Jones, and Eddie Harmon- Jones, School of Psychology, The University of New South Wales. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Eddie Harmon-Jones, School of Psychology, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] T hi s do

- 8. oa dl y. Motivation Science © 2017 American Psychological Association 2018, Vol. 4, No. 2, 95–108 2333-8113/18/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/mot0000079 95 mailto:[email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/mot0000079 an expectation. In this classic study, Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter (1956) were participant observers in a group who believed a cata- strophic flood would occur on a prophesied date in the near future. Many members of the group had abandoned their normal lives in prepara- tion. When the prophesied date passed without catastrophe, they were confronted with evi- dence that violated their expectation. Festinger and colleagues speculated that these individuals experienced dissonance as a result of the dis- confirmation of their beliefs, or a violation of an expectation. Laboratory experiments on dissonance theory have focused primarily on the ways in which individuals reduce dissonance. However, Fest- inger (1957) stated, “There is no guarantee that (a) person will be able to reduce or remove the

- 9. dissonance” (p. 6). Thus, it is possible that the affective state of dissonance can be evoked but not reduced by typical dissonance reduction methods (e.g., attitude change). Moreover, this may especially be the case when the disso- nance-evoking event is minimal. That is, with a minimal evocation of dissonant cognitions, the affective state of dissonance may dissolve quickly and almost on its own via homeostatic or opponent processes. In the present research, we were interested in investigating the minimal circumstances that will evoke the affective state associated with dissonance. Over the decades, dissonance researchers have used a variety of methods to investigate the affective state associated with dissonance. In the 1960s and 1970s, researchers used per- formance on simple and complex tasks to in- vestigate the arousal associated with disso- nance, with the assumption that arousal would improve performance on simple tasks and impair performance on complex tasks (Cottrell & Wack, 1967; Cottrell, Wack, Sekerak, & Rittle, 1968; Pallak & Pittman, 1972; Waterman, 1969). Then, in the 1970s to 1990s, researchers used misattri- bution paradigms to further investigate the arousal and negative valence associated with dissonance, based on the assumption that if in- dividuals were given a different explanation for their affective state, they would not engage in dissonance reduction (Fried & Aronson, 1995; Higgins, Rhodewalt, & Zanna, 1979; Losch & Cacioppo, 1990; Pittman, 1975; Zanna, Hig- gins, & Taves, 1976). Also during these years a few researchers found that dissonance caused

- 10. increased arousal as measured by skin conduc- tance (Elkin & Leippe, 1986; Losch & Ca- cioppo, 1990). However, in all of these studies, traditional dissonance paradigms were used, which likely evoked other psychological con- cerns (e.g., self-worth) in addition to cognitive inconsistency. In the 1990s and 2000s, experiments attempted to present participants with dissonance paradigms that evoked mere cognitive inconsistency, uncon- taminated by self-concerns. These experiments found increased self-reported negative affect (E. Harmon-Jones, 2000a) and skin conductance (E. Harmon-Jones, Brehm, Greenberg, Simon, & Nelson, 1996). In one such experiment, partici- pants were assigned to write that they liked an unpleasant drink (low-choice condition), or were subtly induced to write that they liked it while believing it was their own choice (high-choice condition; E. Harmon-Jones, 2000a). Participants then discarded the statements in the trash. Partic- ipants reported more negative affect in the high- choice condition as compared with low-choice condition (E. Harmon-Jones, 2000a). However, these inconsistencies required ac- tion on the part of the participant (i.e., they wrote a counterattitudinal statement). Would a simpler inconsistency not involving action by the individual be sufficient to evoke the nega- tive affect of dissonance? Simpler Inconsistencies

- 11. Proulx, Inzlicht, and Harmon-Jones (2012) argued that simple inconsistencies could be un- derstood in the same terms as dissonance. Other researchers have argued that the definition of dissonance has become unnecessarily narrow and as a result lost explanatory power (Gawron- ski & Brannon, in press). Returning to Festing- er’s broader definition of dissonance, they ar- gue, would position cognitive consistency as a more fundamental part of information process- ing and provide insights into more phenomena (Gawronski & Brannon, in press). Proulx et al. (2012) proposed that negative affective re- sponses to a variety of inconsistencies could be understood in the same neurocognitive and mo- tivational terms, including cognitively complex inconsistencies like those involved in classic dissonance paradigms and simpler inconsisten- cies like incongruous word pairings (Randles, Proulx, & Heine, 2011). However, these studies 96 LEVY, HARMON-JONES, AND HARMON-JONES T hi s do cu m en t is

- 16. of simple inconsistencies did not measure affec- tive responses. Other bodies of research have found discom- fort in response to simple inconsistencies (Bar- tholow, Fabiani, Gratton, & Bettencourt, 2001; Mendes, Blascovich, Hunter, Lickel, & Jost, 2007; Plaks, Grant, & Dweck, 2005). However, many of these studies included social informa- tion with positive or negative valence already attached (e.g., perceptions and expectations about others’ intelligence, as in Plaks et al., 2005). Evidence of discomfort after a neutral, novel expectancy violation would go further in establishing the central role of inconsistency in creating discomfort. Along these lines, Dreisbach and Fischer (2015) reviewed studies in which they found negative affect after conflict trials in the Stroop task (Dreisbach & Fischer, 2012a). The authors explained this response in the context of Se- quential Control Adaptation, which is an in- crease in cognitive control following the detec- tion of a conflict (see Egner, 2007, for a review). However, it is important to note that these studies still required participant action and effort in encountering these conflicts in tasks with a goal, and were concerned with “adapting to changing task demands” (Dreisbach & Fi- scher, 2012b, p. 1). Evidence of dissonance discomfort in a task where there is no action on the part of the participants and no advantage to an increase in cognitive control would support the idea that simple inconsistencies can evoke dissonance.

- 17. Another body of work that is relevant to the present work is research on perceptual and pro- cessing fluency. For example, some research used sentences that ended with either a strongly expected word (e.g., The stormy seas tossed the BOAT) or a word that was not strongly expected (e.g., He saved up his money and bought a BOAT; Whittlesea, 1993, Experiment 2). Re- sults revealed that sentences with strongly ex- pected endings caused participants to make judgments suggesting they had an illusory feel- ing of familiarity. Other work along these lines has revealed results even more directly relevant to the present work. For instance, word triads with a common remote associate (e.g., SALT DEEP FOAM implying SEA) evoke more pos- itive affect than word triads without a common remote associate (e.g., DREAM BALL BOOK; Topolinski, Likowski, Weyers, & Strack, 2009). These results from the perceptual and process- ing fluency literatures suggest that cognitive processes not too dissimilar from cognitive dis- sonance may evoke affective responses. The current studies aimed to look “beyond attitude– behavior discrepancies . . . uniting . . . phenomena under the umbrella of dissonance theory” (Gawronski & Brannon, in press, p. 3) by testing if a simple inconsistency evoked the affective state of dissonance. We manipulated consistency using sentences where the last word was either congruent with the meaning implied by the beginning of the sentence or incongruent with the meaning implied by the beginning of

- 18. the sentence. We hypothesized that incongruent sentence endings would evoke more negative affect than congruent sentence endings. Study 1 Because self-report measures of affective re- sponses may be relatively insensitive to slight changes in affect and associated with problems of awareness and various biases, we chose to use an adapted form of the Implicit Positive and Negative Affect Test (IPANAT; Quirin, Kazén, & Kuhl, 2009) to measure implicit affective responses to the dissonance manipulation. Here we will briefly explain the conceptual and em- pirical framework of this implicit measure. Strack and Deutsch (2004) proposed that people process information with both a reflec- tive system, based on conceptual propositions and clarifications, and an associative system, which works via the spreading activation of representations. Although self-report measures tap into the reflective system, implicit measures can tap into the associative system, circumvent- ing issues of awareness and biased or erroneous self-reporting. Working from a similar theoretical model, Quirin et al. (2009) developed the IPANAT to measure implicit affect. In this task, participants see neutral nonwords. Participants nominate to what degree these nonwords express each of six positive and negative emotions. As a demon- stration of the measure’s sensitivity, the exper- imenters presented participants with emotion-

- 19. ally arousing pictures either positive (e.g., cute animals) or negative (e.g., a crying child) in valence. After pictures with negative content, participants rated the nonwords as conveying more negative emotions. After pictures with 97DISSONANCE AND DISCOMFORT T hi s do cu m en t is co py ri gh te d by th e A

- 23. to be di ss em in at ed br oa dl y. positive content, participants rated the non- words as conveying more positive emotions. Throughout this article we refer to partici- pants’ responses to the nonwords that make up this measure. These responses reflect the affec- tive valence of participants’ reactions. We pre- dicted that participants’ ratings of nonwords would demonstrate more negative affect after incongruent sentence endings than after congru- ent sentence endings, suggestive that this min- imal dissonance manipulation indeed evoked negative affect. Method

- 24. Participants. Participants were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (n � 199 [127 females]) and were paid 75 cents for their time. All participants were residents of the United States, between 18 and 76 years of age. We de- termined the sample size given an estimated effect size from a previous unpublished exploratory study, by means of an effect size calculator (a priori dependent samples t test, Cohen’s dav � 0.2, � � .90, � � .05, one-tailed). Procedure. Each trial started with fixation asterisks shown for 1,000 ms, then the first word of a sentence for 200 ms, then a blank screen for 300 ms, and then the next word for 200 ms and so on (after Duncan et al., 2009; Thornhill & Van Petten, 2012). Following the offset of the sen- tence-final word, a blank screen occupied the dis- play for a variable interval between 2,300 ms and 2,800 ms. Participants then saw a nonword in green (which distinguished these words from the pre- vious words in black text) for 1,500 ms before it was replaced on screen by a rating scale. Once participants made a rating, they saw a blank screen for 1,000 ms before the next sentence started. Design and materials. Of the 50 sentences seen by each participant, 25 ended with a word incongruent with the contents of the rest of the sentence and 25 ended with a word congruent with the contents of the rest of the sentence (see below for examples). Sentences were presented

- 25. in one of eight pseudorandom orders, to control for order effects. Block and Baldwin (2010) provided the sen- tence stimuli. The full set, along with the sen- tence completion norms, may be downloaded from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 46095540_Cloze_probability_and_completion_ norms_for_498_sentences_Behavioral_and_ neural_validation_using_event-related_potentials. From this set, we chose sentences with the highest cloze probability that also did not have any emo- tional or arousing content. To create incongruent versions of the sentences, we swapped final words with others from the set (after Duncan et al., 2009; Thornhill & Van Petten, 2012). Sentences that ended with a congruent word for some partici- pants ended with an incongruent word for others to control for effects of particular combinations. For instance, all participants saw the words, “She couldn’t start her car without the right . . . .” Some participants saw the sentence end with the incon- gruent ending “teeth.” Other participants saw the congruent ending “keys.” The IPANAT displayed a single 7-point scale after each sentence. Participants saw a nonword, and then saw the question “Do you think this word expresses . . .” and selected one of the following: 1 � “Something very bad or unpleasant,” 2 � “Some- thing fairly bad or unpleasant,” 3 � “Something slightly bad or unpleasant,” 4 � “Something neu- tral,” 5 � “Something slightly good or pleasant,” 6 � “Something fairly good or pleasant,” 7 � “Something very good or pleasant.”

- 26. Our study involved more trials than Quirin et al. (2009), so we developed more nonwords in the same way that they did. To develop our set of nonwords, 72 participants rated 552 non- words in an online survey. They rated nonwords such as “KICAL” and “TOBAL” on valence (from 1 � very unpleasant to 5 � very pleas- ant), familiarity (from 1 � not at all familiar to 5 � extremely familiar), and meaning (from 1 � I have no clue what it means to 5 � I’m sure I know what it means). We first eliminated words below 2.70 or above 3.30 on the valence item. We then eliminated words rated any higher than “not very familiar” on the familiar- ity item. Of the remaining set, we selected the 50 nonwords rated least meaningful on the meaning item. Ratings fell between 1.07 and 1.45 on meaning, with a mean of 1.30. Data analysis. For each participant, we av- eraged across all responses to nonwords after incongruent endings and compared this to the average of all responses to nonwords after con- gruent endings. We predicted mean ratings of nonwords after incongruent sentence endings would be significantly more negative than rat- ings of nonwords after congruent sentences, as 98 LEVY, HARMON-JONES, AND HARMON-JONES T hi s do

- 31. oa dl y. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46095540_Cloze_prob ability_and_completion_norms_for_498_sentences_Behavioral_ and_neural_validation_using_event-related_potentials https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46095540_Cloze_prob ability_and_completion_norms_for_498_sentences_Behavioral_ and_neural_validation_using_event-related_potentials https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46095540_Cloze_prob ability_and_completion_norms_for_498_sentences_Behavioral _ and_neural_validation_using_event-related_potentials https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46095540_Cloze_prob ability_and_completion_norms_for_498_sentences_Behavioral_ and_neural_validation_using_event-related_potentials determined by a paired samples t test. For our studies, predictions were derived from theory, and therefore were made a priori and were di- rectional. As such, the tests for Studies 1 and 2 are one-tailed, as are all confidence intervals (Rosenthal, Rosnow, & Rubin, 2000). Results and Discussion Participants rated nonwords presented after incongruent sentence endings as expressing something more negative (M � 4.07, SD � 0.45) than those after congruent sentence end- ings (M � 4.17, SD � 0.47), t(198) � 2.84, p � .002, dav � .22, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.031, 0.176].

- 32. In support of the hypothesis, participants im- plicitly expressed more negative affect after in- congruent sentences than after congruent sen- tences. This result provides support for the idea that cognitively simple inconsistencies evoke discomfort (Proulx et al., 2012). In the next study, we aimed to replicate the implicit affect finding in a laboratory setting, with the addition of self-report and electrophys- iological measures. Study 2 To replicate and extend the findings of Study 1, we designed a second study including ratings of nonwords like Study 1, as well as self-report items of affective valence and arousal, an elec- tromyographic (EMG) measure of affective re- sponse to sentences, and an electroencephalo- graphic (EEG) measure of responses to the final word of the sentences. Below we discuss the rationale for each of these measures. Self-reported affect is typically measured by asking participants how they feel directly after a manipulation (e.g., Greenberg et al., 1990; Twenge, Catanese, & Baumeister, 2003) and commonly using the Positive and Negative Af- fect Schedule (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). However, research has shown problems with the validity and sensitivity of this measure (C. Harmon-Jones, Bastian, & Harmon-Jones, 2016a, 2016b; E. Harmon-Jones, Harmon- Jones, Abramson, & Peterson, 2009; Pettersson

- 33. & Turkheimer, 2013). Our affect valence mea- sure simply asked participants to recall how positive or negative they felt after incongruent and congruent sentences. Similarly, our self- reported arousal measure simply asked them to recall how aroused they felt after incongruent and congruent sentences. These items require participants to recall and make generalisations about their experience with these trials, which could also introduce hindsight bias and demand characteristics. However recent evidence supports participants’ ability to accurately recall and report their affective states (C. Harmon-Jones, Bastian, & Harmon-Jones, 2016a, 2016b). These issues were why we first used an implicit measure, and why these self-report items are considered as supplementary to our other measures. We examined facial EMG activity after in- congruent and congruent final words of sen- tences. In particular, we recorded activity over the corrugator supercilii muscle, which is lo- cated on the brow above the inner corner of the eye. Corrugator EMG activity is a sensitive measure of negative affective responses to a variety of stimuli (Allen, Harmon-Jones, & Cavender, 2001; Cacioppo & Petty, 1979; Dim- berg, 1982; Larsen, Norris, & Cacioppo, 2003; Schwartz, Fair, Salt, Mandel, & Klerman 1976; Topolinsky & Strack, 2015). We also recorded EEG potentials time- locked to the onset of the final words of each

- 34. sentence. Different components of this potential (known as the event-related potential or ERP) inform our understanding of the neural pro- cesses underlying responses to stimuli. The N400 component of this potential is a negative- going component that peaks over parietal brain regions and is studied in relation to responses to language stimuli (Kutas & Federmeier, 2011). The sentences used in Studies 1 and 2 come from literature investigating the N400 compo- nent of the ERP. Consequently, we investigated this component and its relationship with affec- tive responses. The magnitude of the N400 is associated with the degree of semantic congru- ity a word has for a particular sentence. Incon- gruent sentence endings elicit a greater N400. It is important to note that this is not an affective measure, but acts as a manipulation check that the incongruent sentence endings were in fact perceived as incongruent. We hypothesized that incongruent sentences would lead to greater negative affect than con- gruent sentences, as measured by self-report, corrugator EMG activity, and nonword ratings (i.e., IPANAT). We predicted that incongruent 99DISSONANCE AND DISCOMFORT T hi s do cu

- 39. dl y. sentence endings would cause a larger (i.e., more negative) N400 component than congru- ent sentence endings, by way of a manipulation check. Method Participants. Participants were first-year psychology students at the University of New South Wales participating for course credit (n � 96 [54 females]). All participants were right- handed, between 18 and 30 years old, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. The description of the study invited participants to participate in a study about words, associations, and emotions. We determined the sample size given an estimated effect size from a previous unpublished explor- atory study by means of an effect size calculator (a priori dependent samples t test, Cohen’s dav � 0.2, � � .90, � � .05, one-tailed). Procedure. Participants were fitted with a 64-electrode EEG array, with two reference electrodes on the earlobes. Participants were also fitted with two EMG electrodes over the corrugator muscle. We recorded 4 min of EEG data while participants rested. This allows par- ticipants and their electrode signals to settle. After receiving instructions, participants began viewing sentence trials. Trials were presented in

- 40. the same way as in the online study, but with two rests of 1 min after 60 and 120 trials were completed, to prevent fatigue. Once all 180 trials were finished, participants were debriefed. Design and materials. The design and ma- terials for this study were similar to the online study, except that participants saw 180 sen- tences, of which 90 ended with an incongruent word and 90 ended with a congruent word. We used 180 trials to ensure we had sufficient trials for the EMG and ERP analyses. Self-report items followed the main body of the experiment. Participants completed “The sentences with UNEXPECTED endings made me feel ____” on 7-point scales for affective valence (1 � negative to 7 � positive,) and arousal (1 � unaroused to 7 � aroused). For both of these items, only the endpoints were labeled. Participants completed the same two scales for “sentences with EXPECTED end- ings.” Data processing and analysis. The corru- gator EMG data were processed off-line after Fridlund and Cacioppo (1986). The continu- ous raw EMG signal was band-pass filtered (10 –500 Hz with a 12dB/octave roll-off). The data were then rectified. We exported the average values for two 1,000 ms segments (0 –1,000 ms and 1,000 –2,000 ms) following the onset of the final word of each sentence for each participant. The following stimulus onset appeared between 2,600 ms and 3,100 ms

- 41. after the onset of the final word of a trial so we did not examine the period between 2,000 – 3,000 ms. We subtracted the mean activity in the 200-ms period before the onset of the final word to adjust for baseline activity. We aver- aged the mean activity in both 1,000 ms periods across all incongruent trial values and across all corrected congruent trial values. We compared average activity at each time using paired sam- ples t tests. To process the EEG data, we used Brain Vision Analyzer 2.0. EEG signals were refer- enced to the average signal from the earlobe electrodes. They were then filtered using a 0.1 Hz hi-pass Butterworth filter with a 48 dB/ octave roll-off and a 30 Hz low-pass filter of the same family with a 48 dB/octave roll-off (Foti & Hajcak, 2008; MacNamara, Foti, & Hajcak, 2009). The program identified artifacts in individual channels (signals from particular sites on the scalp) of the EEG data for removal. It removed trials if there was a step in voltage of 50 �V or more within a millisecond, if there was differ- ence of more than 300 �V within 1,000 ms, if the amplitude of the signal exceeded � 100 �V at any point, or if the activity within 100 ms was less than 0.5 �V. Each segment was then base- line corrected and averaged by trial type. This process is in line with previous ERP research (Foti & Hajcak, 2008). To analyze the N400, the time window for data export was 300 –500 ms. The exported

- 42. values for sites Cz, CPz, Pz, CP1, and CP2 were averaged for each trial type (after Thornhill & van Petten, 2012) and compared using a paired samples t test. Results and Discussion For the first 10 participants, a programming error prevented the self-report data being re- corded. We also excluded 10 participants who reported levels of English fluency other than “extremely fluent” on a four-point scale. Our 100 LEVY, HARMON-JONES, AND HARMON-JONES T hi s do cu m en t is co py ri gh te

- 46. an d is no t to be di ss em in at ed br oa dl y. manipulation relied on interrupting the fluency of sentence comprehension, so a high level of fluency was necessary. During the debriefing, the experimenter care- fully probed for participant suspicion and noted whether the participant was suspicious of the hypotheses of the experiment. Twenty-five par-

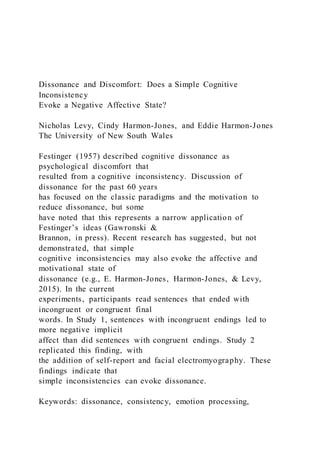

- 47. ticipants out of the remaining 86 had at least some suspicion of the experiment’s hypothesis. Participants were considered suspicious if they said the aim of the experiment was to examine emotions. When these participants are excluded from the analysis, none of the measures differed in significance. As such, we report tests includ- ing their data. See Figure 1 for a graphical representation of normalized means most rele- vant to our conclusions. N400. Participants displayed the typical N400 effect. The N400 component was more negative in response to incongruent sentence endings (M � 2.63 �V, SD � 6.13) than to congruent sentence endings (M � 7.38 �V, SD � 6.44), t(85) � 12.53, p � .001, dav � 0.89, 95% CI [4.12, 5.38]. Thus, our manipula- tion was successful in creating incongruent sen- tence endings. Corrugator EMG activity. Participants sho- wed greater corrugator EMG activity after in- congruent sentence endings (M � 1.03 �V, SD � 4.37) than after congruent sentence end- ings (M � �0.41 �V, SD � 5.45), in the period between 1,000 and 2,000 ms after the onset of the final word, t(85) � 1.80, p � .04, dav � 0.291, 95% CI [0.11 �V, 2.77 �V]. In the 1,000 ms immediately following the onset of the final word (which contains responses related to ori- enting as well; see Dimberg, Thunberg, & Elmehed, 2000), corrugator EMG activity after incongruent sentence endings (M � 0.20 �V, SD � 1.71 �V) was not significantly different

- 48. to EMG activity after congruent sentence end- ings (M � �.20 �V, SD � 3.20 �V), t(85) � 1.27, p � .17, dav � 0.16, 95% CI [�0.30 �V, 1.10 �V]. Implicit Positive and Negative Affect Test. Participants rated nonwords presented after in- congruent sentence endings as expressing something more negative (M � 4.02, SD � Figure 1. Normalized (z score) scores for Study 2 means for corrugator electromyographic (EMG) activity (1,000 –2,000 ms), self-reported arousal, Implicit Positive and Negative Affect Test ratings (IPANAT), and self-reported affective valence in response to incongruent and congruent sentence endings. For corrugator EMG, more positive scores indicate more EMG activity; for self-reported arousal, more positive scores indicate more arousal; for IPANAT, more positive scores indicate more positive affect; and for self-reported affect, more positive scores indicate more positive affect. 101DISSONANCE AND DISCOMFORT T hi s do cu m en

- 53. 0.36) than those presented after congruent end- ings (M � 4.12, SD � 0.35), t(85) � 3.11, p � .002, dav � 0.28, 95% CI [0.05, 0.17]. These results replicate those of Study 1. Self-report. Participants reported feeling more negative after incongruent sentence end- ings (M � 3.92, SD � 1.28) than after congru- ent sentence endings (M � 4.87, SD � 1.37), t(75) � 4.11, p � .001, dav � 0.71, 95% CI [0.56, 1.33]. Participants also reported feeling more aroused after incongruent sentence end- ings (M � 3.72, SD � 1.59) than after congru- ent sentence endings (M � 3.17, SD � 1.27), t(75) � 2.59, p � .006, dav � 0.471, 95% CI [0.20, 0.91]. Conclusion Replicating Study 1, participants expressed more negative affect on the measure of implicit affect in response to incongruent endings than congruent endings. In an extension of Study 1, Study 2 found that participants displayed more corrugator EMG activity to incongruent than congruent endings. However, corrugator EMG activity only differed significantly in the second time period of interest. The first time period showed a difference in the same direction. Given that the first time period is contaminated by orienting (see Dimberg et al., 2000), this weaker difference is understandable. Finally, participants reported feeling more negative af-

- 54. fect and arousal to incongruent than congruent endings. One concern about Study 2 that should be noted is that corrugator EMG could reflect other psychological processes in addition to negative affect. For instance, past research has found that corrugator EMG is related to cognitive effort (de Morree, & Marcora, 2010). However, the inclusion of other measures of negative affect (i.e., self-reports, IPANAT) that have high con- vergent validity mitigates this concern. Future research would benefit from the inclusion of additional measures of negative affect. General Discussion The current studies found negative affective responses to simple inconsistencies across im- plicit (nonword ratings), physiological (corru- gator EMG responses), and self-report mea- sures. This is the first demonstration of dissonance discomfort in response to a simple inconsistency in the absence of information with positive or negative valence already at- tached to it (Plaks et al., 2005) and in the absence of participant action and effort (Dreisbach & Fisher, 2015). Festinger originally conceived dissonance as concerning inconsistencies between “any knowledge, opinion, or belief about the envi- ronment, about oneself, or about one’s behav- ior” (Festinger, 1957, p. 3). The current findings support a return to this broader focus of disso-

- 55. nance research, which would include responses to simpler inconsistencies (Gawronski & Bran- non, in press; E. Harmon-Jones et al., 2015). This return would allow dissonance research to shed light on a wider variety of phenomena (Gawronski & Brannon, in press). Methodological Considerations Although multiple measures of negative af- fect were used in the current studies to make alternative explanations less likely to account for the results, some readers might question whether some of the current effects are due to demand characteristics. We suggest that al- though demand characteristics might be able to explain the self-report affect and arousal differ- ences, demand would not be easily able to ex- plain the results obtained using the more im- plicit measures (EMG, IPANAT). Some readers might suggest that the incon- sistency found in the incongruent sentences could better be described as “meaninglessness.” We concur that inconsistency interferes with meaning or “making sense.” That is, inconsis- tency often evokes a perception of meaningless- ness (Proulx et al., 2012). This link is clear when one tries to think of examples of mean- inglessness without some inconsistency. Others might suggest that participants experienced frustration at not being able to complete the task of comprehending the incongruent sentences. The explicit instructions to participants did not require them to comprehend the sentences, and thus they were unlikely to be frustrated by this

- 56. type of explicit goal. However, they may have experienced frustration because of the violated expectations created by the incongruent sen- tences. Frustration, which is often created by violated expectations, may also fall under the umbrella of cognitive inconsistency, particu- 102 LEVY, HARMON-JONES, AND HARMON-JONES T hi s do cu m en t is co py ri gh te d by th e

- 60. t to be di ss em in at ed br oa dl y. larly in the way Festinger’s original theory de- fined inconsistency. Cognitive inconsistency (dissonant cognitions) is a broad theoretical construct that incorporates expectation viola- tion, challenges to meaning, and frustration (Festinger, 1957). According to Festinger’s original theory, sev- eral variables should determine the degree of discomfort dissonant cognitions cause. One of these is the relevance of the cognitions to each other (Festinger, 1957). In relation to the current experimental methods, the cognition (or expec- tation) created by the sentence stem is relevant

- 61. to (and [in]consistent with) the cognition cre- ated by the last word of the sentence. A word in the final position of a sentence is perceived as relevant to the beginning of the sentence, be- cause past experience has indicated that in most sentences, this connection is meaningful. In other words, individuals read and hear sen- tences in which the stem of the sentence and the final word are both relevant to meaning of that sentence. Because individuals in our experi- ments had experience with the language used, the structure of a sentence imbues the words in that sentence with relevance to each other, even if some of those words are not expected. Our manipulation is effective precisely because words in a sentence are always expected to be relevant to each other. Relation to Other Lines of Research Our findings complement research on con- ceptual and perceptual processing fluency. Con- ceptual fluency research relies on more coherent information (such as a word triad with a com- mon remote associate; e.g., SALT DEEP FOAM implying SEA) being processed more fluently than other information (such as a word triad without a common remote associate; e.g., DREAM BALL BOOK; Topolinski et al., 2009). Perceptual fluency research relies on vi- sually coherent information (such as a picture of a normal cube) being processed more fluently than incoherent visual information (such as a picture of an impossible cube; Topolinski, Erle, & Reber, 2015). Individuals have more positive (less negative) affective reactions to informa-

- 62. tion that is more easily processed, as measured by facial muscle activity (Topolinski et al., 2009, 2015; Winkielman & Cacioppo, 2001), self-reported liking of the stimuli (Mandler, Na- kamura, & Van Zandt, 1987; Reber, Winkiel- man, & Schwarz, 1998; Topolinski & Strack, 2009a), and the affective influence of the stim- uli on subsequent task performance (Reber et al., 1998, Study 1; Topolinski & Strack, 2009b, 2009c). In the processing fluency literature, more flu- ency indicates success in processing, which causes an increase in positive affect (Topolinksi et al., 2015). We believe that this processing fluency research fits with ideas derived from dissonance theory, even though the processing fluency research has focused more on fluency increasing positive affect than on dysfluency increasing negative affect. The present research addresses this latter point and it is consistent with Festinger’s ideas about dissonance theory. That is, although many researchers considered dissonance theory to be an ego-defense theory (Aronson, 1968, 1999), Festinger considered dissonance theory to involve basic perceptual and motivational processes. For example, Fest- inger and colleagues conducted several experi- ments designed to evoke a dissonance between two basic perceptions about reality—visual and tactile (Festinger, Ono, Burnham, & Bam- ber,1967). In these experiments, participants wore prism goggles that made the straight edge of a door appear curved. When the participants touched the straight edge of the door with their

- 63. hands, their perceptual system assimilated the tactile information to create the perception that the door was in fact curved even though it was straight. In other words, the perceptual system had already developed an illusion or a quick- and-easy way to deal with the dissonance. Our findings also converge with recent work on the valence of surprise. Expectancy viola- tions are often surprising (Meyer, Niepel, Ru- dolph, & Schützwohl, 1991). The research lit- erature on the feeling of surprise varies between positing that surprise feels good (Fontaine, Scherer, Roesch, & Ellsworth, 2007), bad (Noordewier & Breugelmans, 2013), or neutral (Mellers, Fincher, Drummond, & Bigony, 2013). One perspective explains this confusion as due to different researchers focusing on dif- ferent time periods during and/or after an unex- pected event (Noordewier, Topolinski, & Van Dijk, 2016). These authors argue that surprise is initially negative, and is very quickly replaced with other feelings that are influenced by an understanding of the unexpected event. Partici- 103DISSONANCE AND DISCOMFORT T hi s do cu m

- 68. y. pants describe their own experience of surprise as significantly more negative when reporting how they felt at the moment that the surprise happens, compared with after a short while (Noordewier & Breugelmans, 2013, Study 1). Participants also rate facial expressions of oth- ers as more negative in the first couple of sec- onds following a positive unexpected event than four seconds after (Noordewier & Breugelmans, 2013, Study 3a). Our study found early negative responses to unexpected events, supporting this perspective on surprise. Dissonance perspec- tives such as the action-based model of disso- nance suggest that surprise may be initially neg- ative because it prevents one from knowing how to behave (E. Harmon-Jones, 1999; E. Harmon- Jones, Amodio, & Harmon-Jones, 2009). Sur- prise indicates a discrepancy between what was expected and what happened, making it difficult to know how to behave. Resolving this discrep- ancy reduces this negative affect and allows easier behavioral responses. Along similar lines, the conflict monitoring hypothesis describes a system that identifies cognitive conflict and adjusts effort and atten- tion in response. The conflict detection system is mediated by activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, and cognitive control is then mediated by activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Botvinick, Braver, Barch, Carter, & Cohen, 2001). Simple response conflicts (Botvinick,

- 69. Nystrom, Fissell, Carter, & Cohen 1999) and conflicts where behavior is inconsistent with the self-concept (Amodio et al., 2004) both evoke this conflict-related anterior cingulate activity. As a result, the conflict monitoring hypothesis can be understood in the same motivational and neurocognitive terms as dissonance processes, as discussed previously (E. Harmon-Jones, 2004; E. Harmon-Jones, Amodio, & Harmon- Jones, 2009; Proulx, Inzlicht, & Harmon-Jones, 2012). Thus, dissonance theory could provide predictions for how individuals resolve conflicts considered in the conflict monitoring literature (e.g., via attitude change, adding cognitions, see Festinger, 1957). It would also suggest that the cognitive conflict monitoring process is intrin- sically affective and motivational in nature. Conclusion Cognitive dissonance theory has gained at- tention for so many years precisely because the research vividly demonstrates the power of af- fective processes to overrule the jurisdiction of cold reason. Given how frequently we come in contact with inconsistency in everyday life, its influence on mental processes is important to better understand. This line of research has the potential to contribute to unifying efforts (e.g., Proulx et al., 2012) in understanding similarities and differences between effects of cognitively simple and cognitively complex conflicts, and bringing the field of psychology closer to a comprehensive understanding of the interaction between affect, motivation, and cognition.

- 70. References Allen, J. J. B., Harmon-Jones, E., & Cavender, J. H. (2001). Manipulation of frontal EEG asymmetry through biofeedback alters self-reported emotional responses and facial EMG. Psychophysiology, 38, 685– 693. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-8986 .3840685 Amodio, D. M., Harmon-Jones, E., Devine, P. G., Curtin, J. J., Hartley, S. L., & Covert, A. E. (2004). Neural signals for the detection of unintentional race bias. Psychological Science, 15, 88 –93. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01502003.x Aronson, E. (1968). Dissonance theory: Progress and problems. In R. P. Abelson, E. Aronson, W. J. McGuire, T. M. Newcomb, M. J. Rosenberg, & P. H. Tannenbaum (Eds.), Theories of cognitive consistency: A sourcebook (pp. 5–27). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally. Aronson, E. (1999). Dissonance, hypocrisy, and the self-concept. Readings about the social animal, 219 –236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10318-005 Bartholow, B. D., Fabiani, M., Gratton, G., & Bet- tencourt, B. A. (2001). A psychophysiological ex- amination of cognitive processing of and affective responses to social expectancy violations. Psycho- logical Science, 12, 197–204. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1111/1467-9280.00336 Block, C. K., & Baldwin, C. L. (2010). Cloze prob- ability and completion norms for 498 sentences:

- 71. Behavioral and neural validation using event- related potentials. Behavior Research Methods, 42, 665– 670. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.3 .665 Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review, 108, 624 – 652. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X .108.3.624 Botvinick, M., Nystrom, L. E., Fissell, K., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (1999). Conflict monitoring versus selection-for-action in anterior cingulate 104 LEVY, HARMON-JONES, AND HARMON-JONES T hi s do cu m en t is co py ri gh

- 76. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.3.665 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.624 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.624 cortex. Nature, 402, 179 –181. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1038/46035 Bradley, M. M., Greenwald, M. K., Petry, M. C., & Lang, P. J. (1992). Remembering pictures: Plea- sure and arousal in memory. Journal of Experi- mental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cog- nition, 18, 379 –390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ 0278-7393.18.2.379 Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1979). Attitudes and cognitive response: An electrophysiological ap- proach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol- ogy, 37, 2181–2199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ 0022-3514.37.12.2181 Cottrell, N. B., Rajecki, D. W., & Smith, D. K. (1974). The energizing effects of postdecision dis- sonance upon performance of an irrelevant task. The Journal of Social Psychology, 93, 81–92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1974.9923132 Cottrell, N. B., & Wack, D. L. (1967). Energizing effects of cognitive dissonance upon dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6, 132–138. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1037/h0024567 Cottrell, N. B., Wack, D. L., Sekerak, G. J., & Rittle, R. H. (1968). Social facilitation of dominant re- sponses by the presence of an audience and the

- 77. mere presence of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 245–250. http://dx.doi .org/10.1037/h0025902 de Morree, H. M., & Marcora, S. M. (2010). The face of effort: frowning muscle activity reflects effort during a physical task. Biological Psychology, 85, 377–382. Dimberg, U. (1982). Facial reactions to facial expres- sions. Psychophysiology, 19, 643– 647. Dimberg, U., Thunberg, M., & Elmehed, K. (2000). Unconscious facial reactions to emotional facial expressions. Psychological Science, 11, 86 – 89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00221 Dreisbach, G., & Fischer, R. (2012a). Conflicts as aversive signals. Brain and Cognition, 78, 94 –98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2011.12.003 Dreisbach, G., & Fischer, R. (2012b). The role of affect and reward in the conflict-triggered adjust- ment of cognitive control. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 342. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/ fnhum.2012.00342 Dreisbach, G., & Fischer, R. (2015). Conflicts as aversive signals for control adaptation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24, 255–260. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0963721415569569 Duncan, C. C., Barry, R. J., Connolly, J. F., Fischer, C., Michie, P. T., Näätänen, R., . . . Van Petten, C. (2009). Event-related potentials in clinical re- search: Guidelines for eliciting, recording, and

- 78. quantifying mismatch negativity, P300, and N400. Clinical Neurophysiology, 120, 1883–1908. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2009.07.045 Egner, T. (2007). Congruency sequence effects and cognitive control. Cognitive, Affective & Behav- ioral Neuroscience, 7, 380 –390. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3758/CABN.7.4.380 Elkin, R. A., & Leippe, M. R. (1986). Physiological arousal, dissonance, and attitude change: Evidence for a dissonance-arousal link and a “don’t remind me” effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 51, 55– 65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ 0022-3514.51.1.55 Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive disso- nance. London, England: Tavistock. Festinger, L., Ono, H., Burnham, C. A., & Bamber, D. (1967). Efference and the conscious experience of perception. Journal of Experimental Psychol- ogy, 74, 1–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0024766 Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1037/10030-000 Fontaine, J. R. J., Scherer, K. R., Roesch, E. B., & Ellsworth, P. C. (2007). The world of emotions is not two-dimensional. Psychological Science, 18, 1050 –1057. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280 .2007.02024.x Foti, D., & Hajcak, G. (2008). Deconstructing reap-

- 79. praisal: Descriptions preceding arousing pictures modulate the subsequent neural response. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20, 977–988. http://dx .doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2008.20066 Fridlund, A. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Guidelines for human electromyographic research. Psycho- physiology, 23, 567–589. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00676.x Fried, C. B., & Aronson, E. (1995). Hypocrisy, mis- attribution, and dissonance reduction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 925–933. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167295219007 Gable, P. A., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2013). Does arousal per se account for the influence of appeti - tive stimuli on attentional scope and the late pos- itive potential? Psychophysiology, 50, 344 –350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12023 Gawronski, B., & Brannon, S. M. (in press). What is cognitive consistency and why does it matter? In E. Harmon-Jones (Ed.), Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psycholo g- ical Association. Gerard, H. B. (1967). Choice difficulty, dissonance, and the decision sequence. Journal of Personality, 35, 91–108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494 .1967.tb01417.x Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., Rosen- blatt, A., Veeder, M., Kirkland, S., & Lyon, D. (1990). Evidence for terror management theory: II.

- 80. The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who threaten or bolster the cultural world- 105DISSONANCE AND DISCOMFORT T hi s do cu m en t is co py ri gh te d by th e A m er

- 85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.55 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.55 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0024766 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10030-000 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10030-000 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02024.x http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02024.x http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2008.20066 http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2008.20066 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00676.x http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00676.x http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167295219007 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12023 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01417.x http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01417.x view. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol- ogy, 58, 308 –318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022- 3514.58.2.308 Harmon-Jones, C., Bastian, B., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2016a). Detecting transient emotional responses with improved self-report measures and instruc- tions. Emotion, 16, 1086 –1096. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1037/emo0000216 Harmon-Jones, C., Bastian, B., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2016b). The Discrete Emotions Questionnaire: A new tool for measuring state self-reported emo- tions. PLOS ONE, 11, e0159915. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0159915 Harmon-Jones, E. (1999). Toward an understanding of the motivation underlying dissonance processes: Is feeling personally responsible for the production

- 86. of aversive consequences necessary to cause dis- sonance effects? In E. Harmon-Jones, & J. Mills (Eds.), Cognitive dissonance: Perspectives on a pivotal theory in social psychology (pp. 71–99). Washington, DC: American Psychological Associ- ation. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10318-004 Harmon-Jones, E. (2000b). Cognitive dissonance and experienced negative affect: Evidence that disso- nance increases experienced negative affect even in the absence of aversive consequences. Person- ality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1490 – 1501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014616720026 12004 Harmon-Jones, E. (2000a). A cognitive dissonance theory perspective on the role of emotion in the maintenance and change of beliefs and attitudes. In N. H. Frijda, A. S. R. Manstead, & S. Bem (Eds.), Emotions and beliefs: How feelings influence thoughts. Cambridge, UK: New York: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ CBO9780511659904.008 Harmon-Jones, E. (2004). Contributions from re- search on anger and cognitive dissonance to un- derstanding the motivational functions of asym- metrical frontal brain activity. Biological Psychology, 67, 51–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j .biopsycho.2004.03.003 Harmon-Jones, E., Amodio, D. M., & Harmon-Jones, C. (2009). Action-Based Model of Dissonance: A review, integration, and expansion of conceptions of cognitive conflict. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 119 –166.

- 87. Harmon-Jones, E., Brehm, J. W., Greenberg, J., Si- mon, L., & Nelson, D. E. (1996). Evidence that the production of aversive consequences is not neces- sary to create cognitive dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70, 5–15. Harmon-Jones, E., Harmon-Jones, C., Abramson, L., & Peterson, C. K. (2009). PANAS positive activa- tion is associated with anger. Emotion, 9, 183–196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014959 Harmon-Jones, E., Harmon-Jones, C., Amodio, D. M., & Gable, P. A. (2011). Attitudes toward emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 101, 1332–1350. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1037/a0024951 Harmon-Jones, E., Harmon-Jones, C., & Levy, N. (2015). An action-based model of cognitive disso- nance processes. Current Directions in Psycholog- ical Science, 24, 184 –189. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1177/0963721414566449 Higgins, E. T., Rhodewalt, F., & Zanna, M. P. (1979). Dissonance motivation: Its nature, persis- tence, and reinstatement. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 15, 16 –34. Kutas, M., & Federmeier, K. D. (2011). Thirty years and counting: Finding meaning in the N400 com- ponent of the event-related brain potential (ERP). Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 621– 647. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.131123 Larsen, J. T., Norris, C. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003).

- 88. Effects of positive and negative affect on electro- myographic activity over zygomaticus major and corrugator supercilii. Psychophysiology, 40, 776 – 785. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-8986.00078 Losch, M. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1990). Cognitive dissonance may enhance sympathetic tonus, but attitudes are changed to reduce negative affect rather than arousal. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26, 289 –304. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1016/0022-1031(90)90040-S MacNamara, A., Foti, D., & Hajcak, G. (2009). Tell me about it: Neural activity elicited by emotional pictures and preceding descriptions. Emotion, 9, 531–543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016251 Mandler, G., Nakamura, Y., & Van Zandt, B. J. S. (1987). Nonspecific effects of exposure on stimuli that cannot be recognized. Journal of Experimen- tal Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cogni- tion, 13, 646 – 648. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ 0278-7393.13.4.646 Mellers, B., Fincher, K., Drummond, C., & Bigony, M. (2013). Surprise: A belief or an emotion? Prog- ress in Brain Research, 202, 3–19. http://dx.doi .org/10.1016/B978-0-444-62604-2.00001-0 Mendes, W. B., Blascovich, J., Hunter, S. B., Lickel, B., & Jost, J. T. (2007). Threatened by the unex- pected: Physiological responses during social in- teractions with expectancy-violating partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 698 –716. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92 .4.698

- 89. Meyer, W. U., Niepel, M., Rudolph, U., & Schütz- wohl, A. (1991). An experimental analysis of sur- prise. Cognition & Emotion, 5, 295–311. Noordewier, M. K., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2013). On the valence of surprise. Cognition and Emo- tion, 27, 1326 –1334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 02699931.2013.777660 106 LEVY, HARMON-JONES, AND HARMON-JONES T hi s do cu m en t is co py ri gh te d by

- 94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014959 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024951 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024951 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0963721414566449 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0963721414566449 http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.131123 http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.131123 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-8986.00078 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031%2890%2990040-S http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031%2890%2990040-S http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016251 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.13.4.646 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.13.4.646 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-62604-2.00001-0 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-62604-2.00001-0 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.698 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.698 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.777660 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.777660 Noordewier, M. K., Topolinski, S., & Van Dijk, E. (2016). The temporal dynamics of surprise. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10, 136 – 149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12242 Pallak, M. S., & Pittman, T. S. (1972). General motivational effects of dissonance arousal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21, 349. Pettersson, E., & Turkheimer, E. (2013). Approach temperament, anger, and evaluation: Resolving a paradox. Journal of personality and social psy- chology, 105, 285. Pittman, T. S. (1975). Attribution of arousal as a

- 95. mediator in dissonance reduction. Journal of Ex- perimental Social Psychology, 11, 53– 63. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(75)80009-6 Plaks, J. E., Grant, H., & Dweck, C. S. (2005). Violations of implicit theories and the sense of prediction and control: Implications for motivated person perception. Journal of Personality and So- cial Psychology, 88, 245–262. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1037/0022-3514.88.2.245 Proulx, T., Inzlicht, M., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2012). Understanding all inconsistency compensation as a palliative response to violated expectations. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16, 285–291. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.04.002 Quirin, M., Kazén, M., & Kuhl, J. (2009). When nonsense sounds happy or helpless: The Implicit Positive and Negative Affect Test (IPANAT). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 500 –516. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016063 Randles, D., Proulx, T., & Heine, S. J. (2011). Turn- frogs and careful-sweaters: Non-conscious percep- tion of incongruous word pairings provokes fluid compensation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 246 –249. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1016/j.jesp.2010.07.020 Reber, R., Winkielman, P., & Schwarz, N. (1998). Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judg- ments. Psychological Science, 9, 45– 48. http://dx .doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00008 Rosenthal, R., Rosnow, R. L., & Rubin, D. B. (2000).

- 96. Contrasts and effect sizes in behavioral research: A correlational approach. New York, NY: Cam- bridge University Press. Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1161–1178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0077714 Schwartz, G. E., Fair, P. L., Salt, P., Mandel, M. R., & Klerman, G. L. (1976). Facial muscle patterning to affective imagery in depressed and nonde- pressed subjects. Science, 192, 489 – 491. http://dx .doi.org/10.1126/science.1257786 Strack, F., & Deutsch, R. (2004). Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Person- ality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 220 –247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1 Thornhill, D. E., & Van Petten, C. (2012). Lexical versus conceptual anticipation during sentence processing: Frontal positivity and N400 ERP com- ponents. International Journal of Psychophysiol- ogy, 83, 382–392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j .ijpsycho.2011.12.007 Topolinski, S., Erle, T. M., & Reber, R. (2015). Necker’s smile: Immediate affective consequences of early perceptual processes. Cognition, 140, 1–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015 .03.004 Topolinski, S., Likowski, K. U., Weyers, P., & Strack, F. (2009). The face of fluency: Semantic coherence automatically elicits a specific pattern of facial muscle reactions. Cognition and Emotion,

- 97. 23, 260 –271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0269993 0801994112 Topolinski, S., & Strack, F. (2009a). The analysis of intuition: Processing fluency and affect in judge- ments of semantic coherence. Cognition and Emo- tion, 23, 1465–1503. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 02699930802420745 Topolinski, S., & Strack, F. (2009b). The architecture of intuition: Fluency and affect determine intuitive judgments of semantic and visual coherence and judgments of grammaticality in artificial grammar learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 138, 39 – 63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ a0014678 Topolinski, S., & Strack, F. (2009c). Scanning the “fringe” of consciousness: What is felt and what is not felt in intuitions about semantic coherence. Consciousness and Cognition, 18, 608 – 618. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2008.06.002 Topolinsky, S., & Strack, F. (2015). Corrugator ac- tivity confirms immediate negative affect in sur- prise. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1– 8. Twenge, J. M., Catanese, K. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2003). Social exclusion and the deconstructed state: Time perception, meaninglessness, lethargy, lack of emotion, and self-awareness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 409 – 423. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.409 Waterman, C. K. (1969). The facilitating and in- terfering effects of cognitive dissonance on sim-

- 98. ple and complex paired associates learning tasks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychol- ogy, 5, 31– 42. Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514 .54.6.1063 Whittlesea, B. W. (1993). Illusions of familiarity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 19, 1235–1253. http://dx .doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.19.6.1235 107DISSONANCE AND DISCOMFORT T hi s do cu m en t is co py ri

- 103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016063 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.07.020 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.07.020 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00008 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00008 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0077714 http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1257786 http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1257786 http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.12.007 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.12.007 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015.03.004 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015.03.004 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699930801994112 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699930801994112 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699930802420745 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699930802420745 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014678 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014678 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.concog. 2008.06.002 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.409 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.19.6.1235 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.19.6.1235 Winkielman, P., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2001). Mind at ease puts a smile on the face: Psychophysiological evidence that processing facilitation elicits positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol- ogy, 81, 989 –1000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ 0022-3514.81.6.989 Zanna, M. T., Higgins, E. T., & Taves, P. A. (1976). Is dissonance phenomenologically aversive? Journal of

- 104. Experimental Social Psychology, 12, 530 –538. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(76)90032-9 Received May 13, 2017 Revision received August 14, 2017 Accepted August 15, 2017 � Members of Underrepresented Groups: Reviewers for Journal Manuscripts Wanted If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts for APA journals, the APA Publications and Communications Board would like to invite your participation. Manuscript reviewers are vital to the publications process. As a reviewer, you would gain valuable experience in publishing. The P&C Board is particularly interested in encouraging members of underrepresented groups to participate more in this process. If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts, please write APA Journals at [email protected] Please note the following important points: • To be selected as a reviewer, you must have published articles in peer-reviewed journals. The experience of publishing provides a reviewer with the basis for preparing a thorough, objective review. • To be selected, it is critical to be a regular reader of the five to six empirical journals that are most central to the area or journal for which you would like to review. Current

- 105. knowledge of recently published research provides a reviewer with the knowledge base to evaluate a new submission within the context of existing research. • To select the appropriate reviewers for each manuscript, the editor needs detailed information. Please include with your letter your vita. In the letter, please identify which APA journal(s) you are interested in, and describe your area of expertise. Be as specific as possible. For example, “social psychology” is not sufficient—you would need to specify “social cognition” or “attitude change” as well. • Reviewing a manuscript takes time (1– 4 hours per manuscript reviewed). If you are selected to review a manuscript, be prepared to invest the necessary time to evaluate the manuscript thoroughly. APA now has an online video course that provides guidance in reviewing manuscripts. To learn more about the course and to access the video, visit http://www.apa.org/pubs/ authors/review-manuscript-ce-video.aspx. 108 LEVY, HARMON-JONES, AND HARMON-JONES T hi s do cu

- 110. dl y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.989 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.989 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031%2876%2990032- 9Dissonance and Discomfort: Does a Simple Cognitive Inconsistency Evoke a Negative Affective State?Cognitive Dissonance and AffectSimpler InconsistenciesStudy 1MethodParticipantsProcedureDesign and materialsData analysisResults and DiscussionStudy 2MethodParticipantsProcedureDesign and materialsData processing and analysisResults and DiscussionN400Corrugator EMG activityImplicit Positive and Negative Affect TestSelf- reportConclusionGeneral DiscussionMethodological ConsiderationsRelation to Other Lines of ResearchConclusionReferences ATTITUDES ESTABLISHED BY CLASSICAL CONDITIONING1 ARTHUR W. STAATS AND CAROLYN K. STAATS Arizona State College at Tempe O SGOOD and Tannenbaum have stated, "... The meaning of a concept is its location in a space denned by some number of factors or dimensions, and attitude toward a concept is its projection onto one of these dimensions defined as 'evaluative' " (9,

- 111. p. 42). Thus, attitudes evoked by concepts are considered part of the total meaning of the concepts. A number of psychologists, such as Cofer and Foley (1), Mowrer (5), and Osgood (6, 7), to mention a few, view meaning as a response—an implicit response with cue functions which may mediate other responses. A very similar analysis has been made of the concept of attitudes by Doob, who states, " 'An attitude is an implicit response . . . which is considered socially significant in the individual's society' " (2, p. 144). Doob further emphasizes the learned character of attitudes and states, "The learning process, therefore, is crucial to an understanding of the behavior of attitudes" (2, p. 138). If attitudes are to be considered responses, then the learning process should be the same as for other responses. As an example, the principles of classical conditioning should apply to attitudes. The present authors (12), in three experi- ments, recently conditioned the evaluative, potency, and activity components of word meaning found by Osgood and Suci (8) to contiguously presented nonsense syllables. The results supported the conception that meaning is a response and, further, indicated that word meaning is composed of components which can be separately conditioned. The present study extends the original experiments by studying the formation of attitudes (evaluative meaning) to socially

- 112. significant verbal stimuli through classical con- ditioning. The socially significant verbal stimuli were national names and familiar masculine names. Both of these types of 1 This study is part of a series of studies of verbal behavior being conducted by the authors at Arizona State College at Tempe, The project is sponsored by the Office of Naval Research (Contract Number NONR- 2305 (00)), Arthur W. Staats, principal investigator. stimuli, unlike nonsense syllables, would be expected to evoke attitudinal responses on the basis of the pre-experimental experience of the 5s. Thus, the purpose of the present study is to test the hypothesis that attitudes already elicited by socially significant verbal stimuli can be changed through classical conditioning, using other words as unconditioned stimuli. METHOD Subjects Ninety-three students in elementary psychology participated in the experiments as 5s to fulfill a course requirement. Procedure The general procedure employed was the same as in the previous study of the authors (12). Experiment I,—The procedures were administered to the 5s in groups. There were two groups with one half of the 5s in each group. Two types of stimuli were used:

- 113. national names which were presented by slide pro- jection on a screen (CS words) and words which were presented orally by the E (US words), with 5s required to repeat the word aloud immediately after E had pronounced it. Ostensibly, 5s' task was to separately learn the verbal stimuli simultaneously presented in the two different ways. Two tasks were first presented to train the 5s in the procedure and to orient them properly for the phase of the experiment where the hypotheses were tested. The first task was to learn five visually presented national names, each shown four times, in random order. 5s' learning was tested by recall. The second task was to learn 33 auditorily presented words. 5s repeated each word aloud after E. 5s were tested by presenting 12 pairs of words. One of each pair was a word that had just been presented, and 5s were to recognize which one. The 5s were then told that the primary purpose of the experiment was to study "how both of these types of learning take place together—the effect that one has upon the other, and so on." Six new national names were used for visual presentation: German, Swedish, Italian, French, Dutch, and Greek served as the C5s. These names were presented in random order, with exposures of five sec. Approximately one sec. after the CS name appeared on the screen, E pronounced the US word with which it was paired. The intervals between exposures were less than one sec. 5s were told they could learn the visually presented names by just looking at them but that they should simultaneously concentrate on pronouncing the auditorily presented words aloud and to themselves, since there would be

- 114. many of these words, each presented only once. 37 38 ARTHUR W. STAATS AND CAROLYN K. STAATS The names were each visually presented 18 times in random order, though never more than twice in succession, so that no systematic associations were formed between them. On each presentation, the CS name was paired with a different auditorily presented word, i.e., there were 18 conditioning trials. CS names were never paired with US words more than once so that stable associations were not formed between them. Thus, 108 different US words were used. The CS names, Swedish and Dutch, were always paired with US words with evaluative meaning. The other four CS names were paired with words which had no systematic meaning, e.g., chair, with, twelve. For Group 1, Dutch was paired with different words which had positive evaluative meaning, e.g., gift, sacred, happy; and Swedish was paired with words which had negative evaluative meaning, e.g., bitter, ugly, failure,2 For Group 2, the order of Dutch and Swedish was reversed so that Dutch was paired with words with negative evaluative meaning and Swedish with positive meaning words. When the conditioning phase was completed, 5s were told that E first wished to find out how many of the visually presented words they remembered. At the same time, they were told, it would be necessary to find out how they/eW about the words since that might have affected how the words were learned. Each S was

- 115. given a small booklet in which there were six pages. On each page was printed one of the six names and a semantic differential scale. The scale was the seven- point scale of Osgood and Suci (8), with the con- tinuum from pleasant to unpleasant. An example is as follows: German pleasant: : : : : : : .'unpleasant The 5s were told how to mark the scale and to indicate at the bottom of the page whether or not the word was one that had been presented. The 5s were then tested on the auditorily presented words. Finally, they were asked to write down anytlu'ng they had thought about the experiment, especially the purpose of it, and so on, or anything they had thought of during the experiment. It was explained that this might have affected the way they had learned. Experiment //.—The procedure was exactly re- peated with another group of 5s except for the CS names. The names used were Harry, Tom, Jim, Ralph, Bill, and Bob. Again, half of the 5s were in Group 1 and half in Group 2. For Group 1, Tom was paired with positive evaluative words and Bill with negative words. For Group 2 this was reversed. The semantic differential booklet was also the same except for the C5 names. Design The data for the two experiments were treated in the same manner. Three variables were involved in the 2 The complete list of CS-US word pairs is not pre-

- 116. sented here, but it has been deposited with the American Documentation Institute. Order Document No. 5463 from ADI Auxiliary Publications Project, Photo- duplication Service, Library of Congress, Washington 25, D. C., remitting in advance §1.25 for microfilm or SI.25 for photocopies. Make checks payable to Chief, Photoduphcation Service, Library of Congress. design: conditioned meaning (pleasant and unpleasant); C5 names (Dutch and Swedish, or Tom and Bill); and groups (1 and 2). The scores on the semantic differential given to each of the two CS words were analyzed in a 2 x 2 latin square as described by Lindquist (4, p. 278) for his Type II design. RESULTS The 17 5s who indicated they were aware of either of the systematic name-word relation- ships were excluded from the analysis. This was done to prevent the interpretation that the conditioning of attitudes depended upon awareness. In order to maintain a counter- balanced design when these 5s were excluded, four 5s were randomly eliminated from the analysis. The resulting Ns were as follows: 24 in Experiment I and 48 in Experiment II. Table 1 presents the means and SDs of the meaning scores for Experiments I and II. The table itself is a representation of the 2 X 2 design for each experiment. The pleasant TABLE 1

- 117. MEANS AND SDs OF CONDITIONED ATTITUDE SCORES Names Dutchum^u Swedish Expen- ment Group Mean SD Mean SD I 1 2 2.67 2.67 .94 1.31 3.42 1.83 1.50 .90 Tom Bill ment II Group 1 2 Mean 2.71 3.42

- 118. SD 2.01 2.55 Mean 4.12 1.79 SD 2.04 1.07 Note.—On the scales, pleasant is I, unpleasant 7. TABLE 2 SUMMARY OF THE RESULTS OF THE ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE FOR EACH EXPERIMENT Source Between 5s Groups Error Within Conditioned attitude Names Residual

- 120. 1 46 1 1 46 95 MS 15.84 3.17 55.51 .26 5.30 F 5.00* 10.47** .05 ' t < .05. "p < .01. ATTITUDES ESTABLISHED BY CLASSICAL CONDITIONING 39

- 121. extreme of the evaluative scale was scored 1, the unpleasant 7. The analysis of the data for both experi- ments is presented in Table 2, The results of the analysis indicate that the conditioning occurred in both cases. In Experiment I, the F for the conditioned attitudes was significant at better than the .05 level. In Experiment II, the F for the conditioned attitudes was signifi- cant at better than the .01 level. In both experiments the F for the groups variable was significant at the .05 level. DISCUSSION It was possible to condition the attitude component of the total meaning responses of US words to socially significant verbal stimuli, without Ss' awareness. This conception is schematized in Fig. 1, and in so doing, the way the conditioning in this study was thought to have taken place is shown more specifically. The national name Dutch, in this example, is presented prior to the word pretty. Pretty elicits a meaning response. This is schematized in the figure as two component responses; an evaluative response rpy (in this example, the words have a positive value), and the other distinctive responses that characterize the meaning of the word, Rp. The pairing of Dutch and pretty results in associations between Dutch and rpv, and Dutch and Rp. In the fol- lowing presentations of Dutch and the words sweet and healthy, the association between Dutch and rPv is further strengthened. This is

- 122. not the case with associations RP, Rs, and RH, CS DUTCH ^.-=u-_ _ . "PRETTY. DUTCH -HEAI/DHY FIG. 1. THE CONDITIONING or A POSITIVE ATTITUDE. THE HEAVINESS OF LINE REPRESENTS STRENGTH OP ASSOCIATION since they occur only once and are followed by other associations which are inhibitory. The direct associations indicated in the figure between the name and the individual words would also in this way be inhibited. It was not thought that a rating response was conditioned in this procedure but rather an implicit attitudinal response which medi- ated the behavior of scoring the semantic differential scale. It is possible, with this con- ception, to interpret two studies by Razran (10, 11) which concern the conditioning of rat- ings. Razran found that ratings of ethnically labeled pictures of girls and sociopolitical slo- gans could be changed by showing these stimuli while Ss were consuming a free lunch and, in the case of the slogans, while the 5s were presented with unpleasant olfactory stimula-