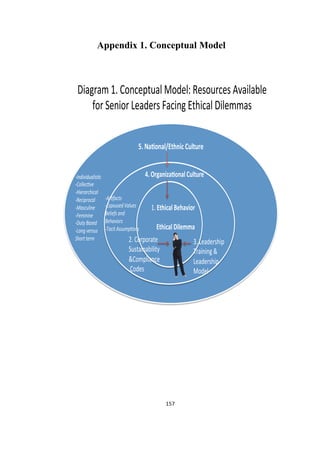

This dissertation explores the influences on senior leaders when facing ethical dilemmas at work. A conceptual framework identifies five potential influences: 1) theories of moral reasoning and judgment, 2) corporate sustainability initiatives and compliance functions, 3) leadership training, 4) organizational culture, and 5) ethnic/national culture. Interviews with 30 senior executives from diverse cultural backgrounds explore which influences impact their understanding and resolution of ethical dilemmas. The conclusions question assumptions about compliance functions and training, and emphasize the importance of personal networks and cultural approaches to managing power relations within those networks.