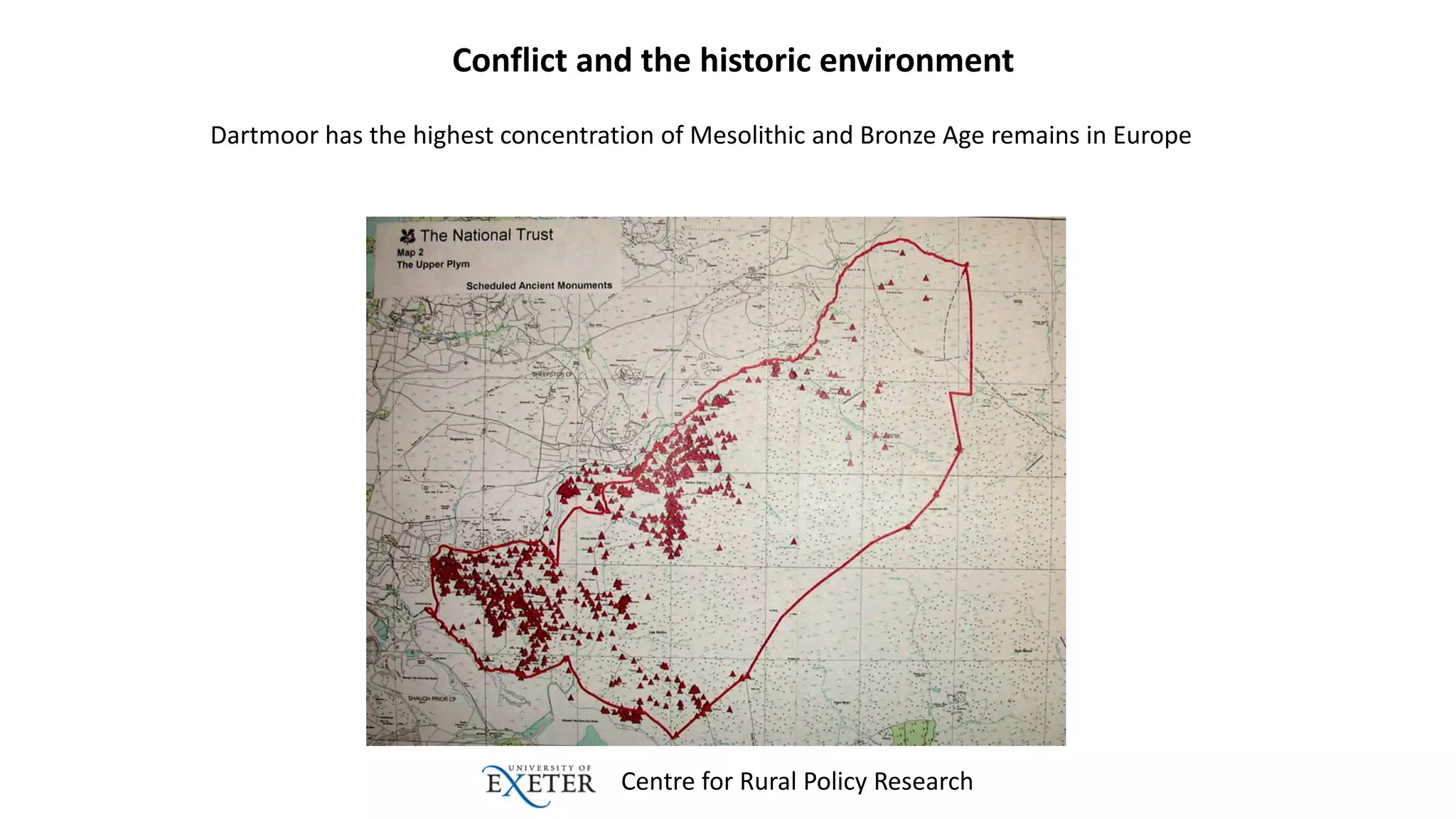

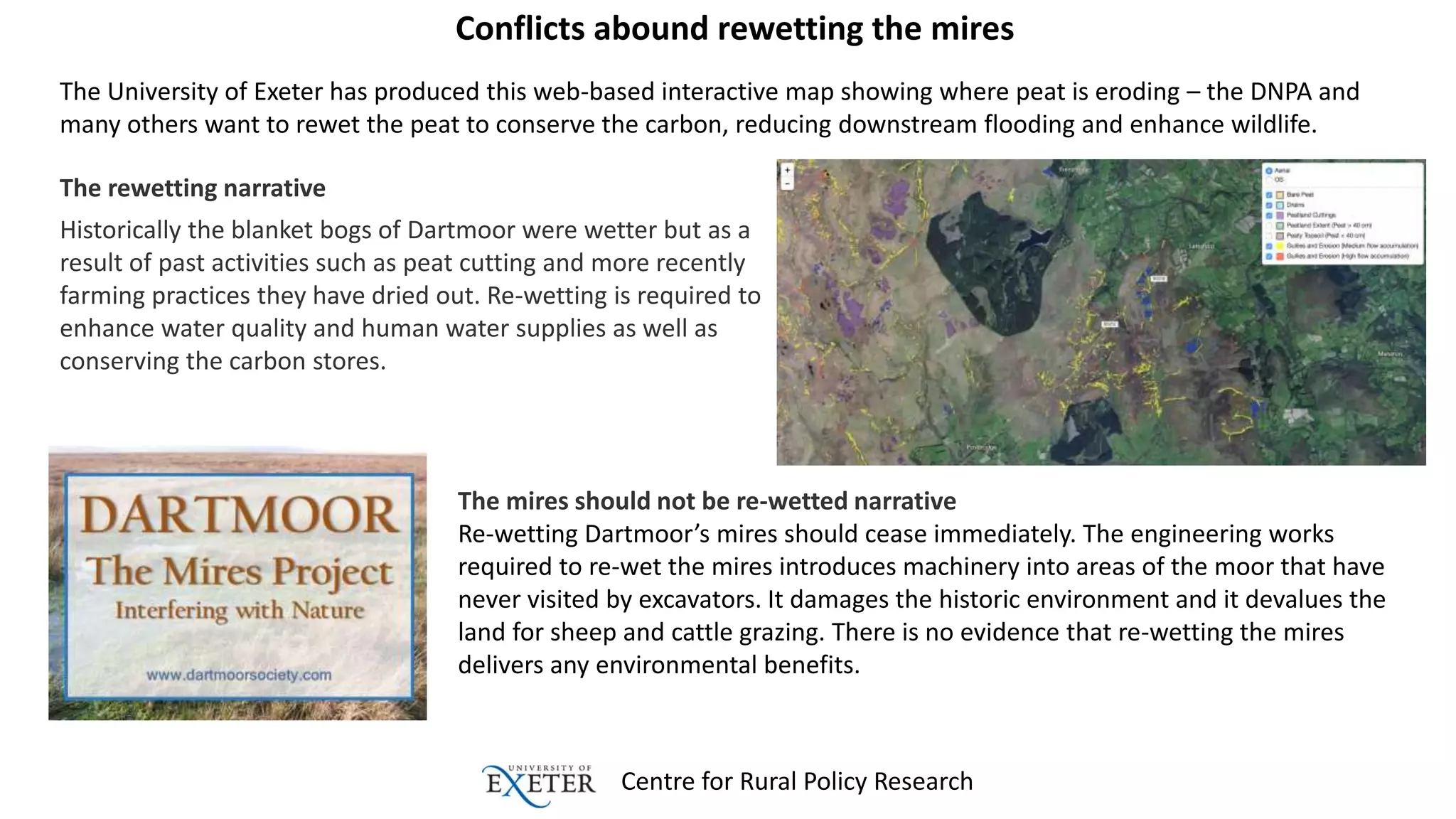

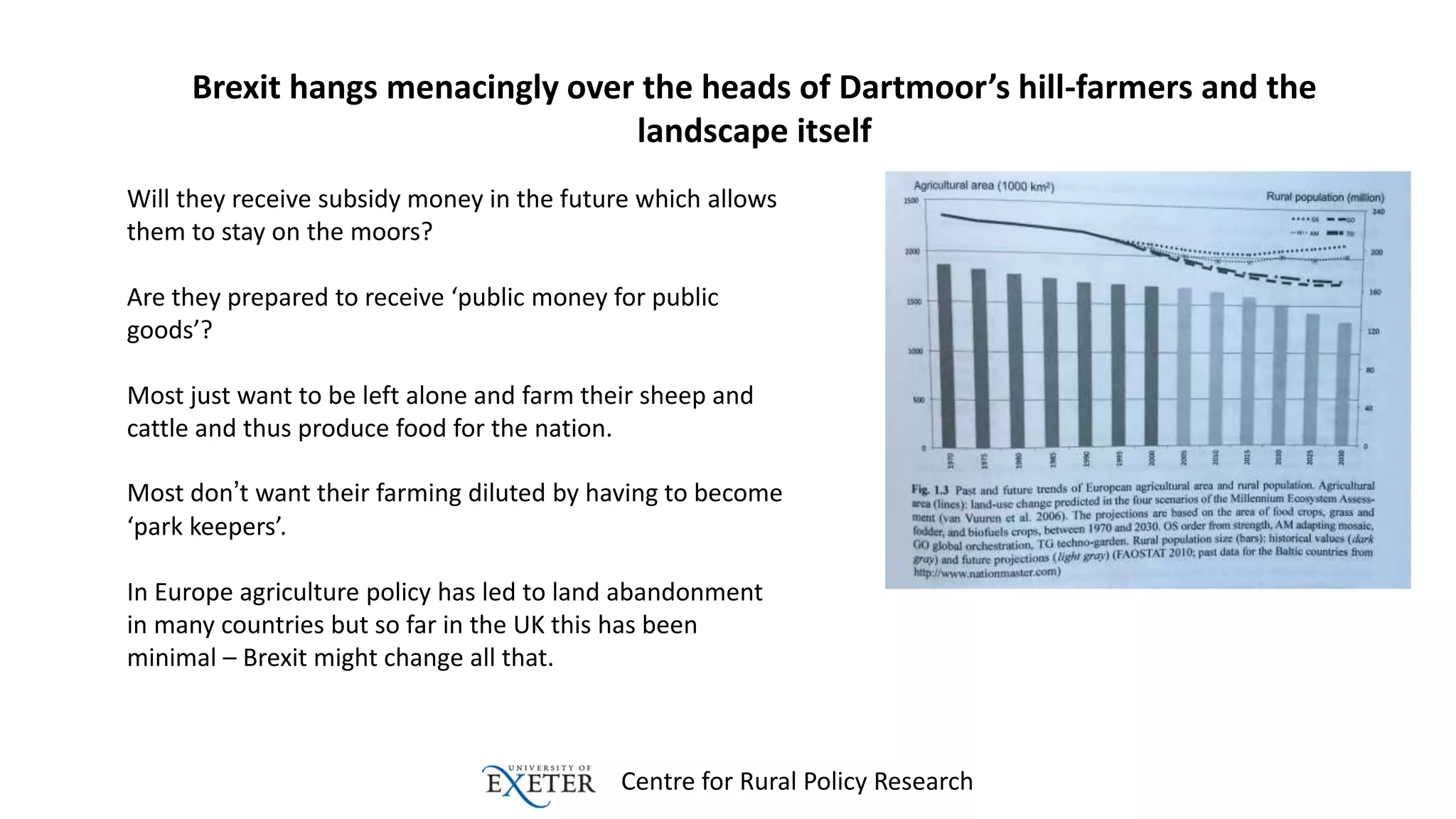

The document outlines the complex history and current challenges facing Dartmoor National Park, including its cultural, agricultural, and environmental narratives. It highlights the struggles of hill-farmers amidst modern pressures such as Brexit, atmospheric pollution, and differing public interests, leading to conflicts over land management and conservation practices. The text also discusses the importance of stakeholders finding a balanced approach to maintain the landscape's ecological health while supporting local farming traditions.