Psychological Science21(12) 1770 –1776© The Author(s) 2010.docx

- 1. Psychological Science 21(12) 1770 –1776 © The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0956797610387441 http://pss.sagepub.com A well-established finding is that mood interacts with cogni- tive processing (for a review, see Isen, 1999), with executive functioning implicated as a possible source of the effects of this interaction (Mitchell & Phillips, 2007). Positive mood leads to enhanced cognitive flexibility,1 whereas negative mood may reduce (or may not affect) cognitive flexibility (for a review, see Ashby, Isen, & Turken, 1999). Category learning has also been associated with cognitive flexibility (Ashby et al., 1999; Maddox, Baldwin, & Markman, 2006), making cat- egory learning well suited to the study of the effects of mood on cognition. For example, Ashby, Alfonso-Reese, Turken, and Waldron (1998) predicted that depressed subjects should be impaired in learning rule-described (RD) category sets. Smith, Tracy, and Murray (1993) supported this prediction and also found that depressed subjects were not impaired when learning non-RD categories. However, the more general ques- tion of how induced positive and negative mood states influ- ence category learning remains unanswered. We addressed this question by using two kinds of categories, one in which learning is thought to be enhanced by cognitive flexibility and one in which learning is not thought to be enhanced by cogni- tive flexibility (Maddox et al., 2006). Our starting point was the competition between verbal and

- 2. implicit systems (COVIS) theory, which posits the existence of separate explicit and implicit category-learning systems (Ashby et al., 1998). The explicit system enables people to learn RD categories and is associated with the prefrontal cor- tex (PFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). RD cate- gory learning uses hypothesis testing, rule selection, and inhibition to find and apply rules that can be verbalized, and it is influenced by cognitive flexibility. The implicit system enables people to learn non-RD categories, relies on connec- tions between visual cortical areas and the basal ganglia, and is not affected by cognitive flexibility. This system is likely procedural in nature and dependent on a dopamine-mediated reward signal (Maddox, Ashby, Ing, & Pickering, 2004). RD and non-RD category sets have been dissociated behaviorally (for a review, see Maddox & Ashby, 2004) and neurobiologi- cally (Nomura et al., 2007), making them appropriate for the study of mood effects. We argue that positive mood increases cognitive flexibility, and this effect enhances the explicit category-learning system Corresponding Author: Ruby T. Nadler, The University of Western Ontario, Department of Psychology, Social Science Centre, Room 7418, 1151 Richmond St., London, Ontario, Canada N6A 5C2 E-mail: [email protected] Better Mood and Better Performance: Learning Rule-Described Categories Is Enhanced by Positive Mood Ruby T. Nadler, Rahel Rabi, and John Paul Minda The University of Western Ontario

- 3. Abstract Theories of mood and its effect on cognitive processing suggest that positive mood may allow for increased cognitive flexibility. This increased flexibility is associated with the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex, both of which play crucial roles in hypothesis testing and rule selection. Thus, cognitive tasks that rely on behaviors such as hypothesis testing and rule selection may benefit from positive mood, whereas tasks that do not rely on such behaviors should not be affected by positive mood. We explored this idea within a category-learning framework. Positive, neutral, and negative moods were induced in our subjects, and they learned either a rule-described or a non- rule-described category set. Subjects in the positive-mood condition performed better than subjects in the neutral- or negative-mood conditions in classifying stimuli from rule- described categories. Positive mood also affected the strategy of subjects who classified stimuli from non-rule-described categories. Keywords frontal lobe, emotions, hypothesis testing, selective attention, response inhibition Received 4/7/10; Revision accepted 6/28/10 Research Report Better Mood and Better Performance 1771 mediated by the PFC (Ashby et al., 1999; Ashby & Ell, 2001;

- 4. Minda & Miles, 2010). We base our predictions on two lines of research. First, Ashby et al. (1999) hypothesized that posi- tive affect is associated with enhanced cognitive flexibility as a result of increased dopamine in the frontal cortical areas of the brain. Second, the COVIS theory predicts that increased dopamine in the PFC and ACC should enhance learning on RD tasks, and reduced dopamine should impair learning on RD tasks (Ashby et al., 1998). Thus, positive mood should be associated with enhanced RD category learning, an important prediction that has not to our knowledge been tested directly. We induced a positive, neutral, or negative mood in sub- jects and presented them with one of two kinds of category sets that have been widely used in the category-learning litera- ture (Ashby & Maddox, 2005). These sets consisted of sine- wave gratings (Gabor patches) that varied in spatial frequency and orientation. The RD set of Gabor patches required learners to find a single-dimensional rule in order to correctly classify the stimuli on the basis of frequency but not orientation, and the non-RD, information-integration (II) set of Gabor patches required learners to assess both orientation and frequency. Subjects in the RD condition were able to formulate a verbal rule to ensure optimal performance, but subjects in the II con- dition were not able to form a rule that could be easily verbalized. We predicted that subjects in a positive mood, compared with those in a neutral or negative mood, would perform better when learning RD categories. It was unclear whether a nega- tive mood would impair RD learning relative to a neutral mood, as the effects of negative mood on cognitive processing are variable and difficult to predict (for a review, see Isen, 1990). Because the PFC and the ACC do not mediate the implicit system, we did not expect mood to affect II category learning.

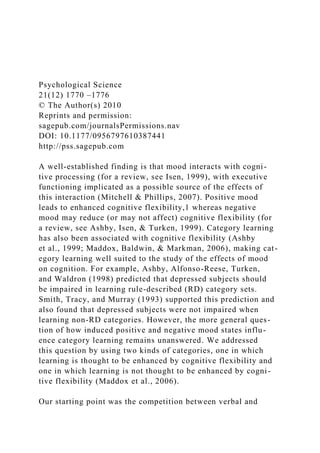

- 5. Method Subjects Subjects were 87 university students (61 females and 26 males), who received $10.00 or course credit for participation. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three mood- induction conditions and one of the two category sets. Six sub- jects who scored below 50% on the categorization task were excluded from data analysis. Materials We used a series of music clips and video clips from YouTube2 to establish affective states. We verified that these clips evoked the intended emotions by conducting a pilot study. After each viewing or listening, subjects in the pilot study (7 graduate students, who did not participate in the main experiment) rated how the clip made them feel on a 7-point scale, which ranged from 1 (very sad) to 4 (neutral) to 7 (very happy). Table 1 shows the complete list of clip selections and the average rat- ings by pilot subjects; it also denotes the clips selected for the main experiment. As a manipulation check during the main experiment, we queried subjects with the Positive and Nega- tive Affect Schedule (PANAS) after using the selected clips to induce moods. The PANAS assesses positive and negative affective dimensions (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The Gabor patches used in the main experiment were gen- erated according to established methodologies (see Ashby & Gott, 1988; Zeithamova & Maddox, 2006). For each category (RD and II), we randomly sampled 40 values from a multivari- ate normal distribution described by that category’s parame- ters (shown in Table 2). The resulting structures for the RD and II category sets are illustrated in Figure 1.3 We used the PsychoPy software package (Pierce, 2007) to generate a Gabor patch corresponding to each coordinate sampled from the mul-

- 6. tivariate distributions. Procedure In the main experiment, subjects were assigned randomly to one of three mood-induction conditions (positive, neutral, or negative), as well as to one of two category sets (RD or II). Table 1. Music and Video Clips Used in the Pilot Study Selection Average subject rating Positive music Mozart: “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik—Allegro”* 6.57 Handel: “The Arrival of the Queen of Sheba” 5.00 Vivaldi: “Spring” 6.14 Neutral music Mark Salona: “One Angel’s Hands”* 3.86 Linkin Park: “In the End (Instrumental)” 4.14 Stephen Rhodes: “Voice of Compassion” 3.29 Negative music Schindler’s List Soundtrack: “Main Theme”* 2.00 I Am Legend Movie Theme Song 2.71 Distant Everyday Memories 2.57 Positive video Laughing Baby* 6.57 Whose Line Is It Anyway: Sound Effects 6.43 Where the Hell Is Matt? 6.00 Neutral video Antiques Roadshow Television Show* 4.14 Facebook on 60 Minutes 3.71 Report About the Importance of Sleep 4.29 Negative video Chinese Earthquake News Report* 1.43

- 7. Madison’s Story (About Child With Cancer) 1.71 Death Scene From the Film The Champ 1.86 Note: Clips were taken from the YouTube Web site. Asterisks denote clips that were used in the main experiment. 1772 Nadler et al. Subjects were presented with the clips (music first, then video) from their assigned mood condition and then completed the PANAS so we could ensure that the mood induction was successful. After receiving instructions, subjects performed a category- learning task on a computer. On each trial, a Gabor patch appeared in the center of the screen, and subjects pressed the “A” or the “B” key to classify the stimulus. Subjects who viewed the RD category set (Fig. 1a) had to find a single- dimensional rule to correctly classify the stimuli on the basis of the frequency of the grating, while ignoring the more salient dimension of orientation. The optimal verbal rule for such classification could be phrased as follows: “Press ‘A’ if the stimulus has three or more stripes; otherwise, press ‘B.’” The non-RD, II category set (Fig. 1b) required learners to assess both orientation and frequency. There was no rule for this set that could be easily verbalized to allow for optimal perfor- mance. In both conditions, feedback (“CORRECT” or “INCORRECT”) was presented after each response. Subjects completed four unbroken blocks of 80 trials each (320 total). The presentation order of the 80 stimuli was randomly gener- ated within each block for each subject.

- 8. Results PANAS Scores on the Positive Affect scale were as follows—positive- mood condition: 2.89; neutral-mood condition: 2.45; and neg- ative-mood condition: 2.42. A significant effect of mood on positive affect was found, F(2, 78) = 3.98, p < .05, η2 = .093. Positive-mood subjects showed only marginally more positive Table 2. Distribution Parameters for the Rule-Described and Non-Rule- Described Category Sets Category set and category µ f µ o σ f 2 σ o 2 cov f,o Rule-described Category A 280 125 75 9,000 0 Category B 320 125 75 9,000 0 Non-rule-described Category A 268 157 4,538 4,538 435 Category B 332 93 4,538 4,538 4,351 Note: Dimensions are in arbitrary units; see Figure 1 for scaling

- 9. factors. The sub- scripted letters o and f refer to orientation and frequency, respectively. –200 –100 0 100 200 300 400 500 –100 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 O rie nt at io n Frequency Rule-Described –200

- 10. –100 0 100 200 300 400 500 –100 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 O rie nt at io n Frequency Non-Rule-Described ba Fig. 1. Structures used in the (a) rule-described category set and (b) non-rule-described, information-integration category set. Category A stimuli are represented by light circles, and Category B stimuli are represented by dark circles. The solid lines show the optimal

- 11. decision boundaries between the stimuli. The values of the stimulus dimensions are arbitrary units. Each stimulus was created by converting the value of these arbitrary units into a frequency value (cycles per stimulus) and an orientation value (degree of tilt). For both category sets, the grating frequency (f) was calculated as 0.25 + (x f /50) cycles per stimulus, and the grating orientation (o) was calculated as xo × (π/20)°. The Gabor patches are examples of the actual stimuli seen by subjects. Better Mood and Better Performance 1773 affect than neutral-mood subjects did (p < .06), but they showed significantly more positive affect than negative-mood subjects did (p < .05). These scores indicate that the mood- induction procedures were effective. Scores on the Negative Affect scale were as follows—positive-mood condition: 1.15; neutral-mood condition: 1.18; and negative-mood condition: 2.13. A significant effect of mood on negative affect was found, F(2, 78) = 30.36, p < .001, η2 = .438, with negative- mood subjects showing significantly more negative affect than positive- and neutral-mood subjects did (p < .0001 in both cases). These results again indicate that the mood-induction procedures were effective. Category learning Figure 2 shows the learning curve (average proportion of cor- rect responses in Blocks 1–4) for each condition and each cat-

- 12. egory set. A mixed analysis of variance revealed main effects of category set, F(1, 75) = 31.94, p < .001, η2 = .257; mood, F(2, 75) = 4.40, p < .05, η2 = .071; and block, F(3, 225) = 41.33, p < .001, η2 = .322. It also revealed a significant interac- tion between mood and category set, F(2, 75) = 4.17, p < .05, η2 = .067. We conducted two separate analyses of variance (one for the RD category and one for the II category) to exam- ine this interaction. A main effect of mood on overall performance was found for the RD category set, F(2, 35) = 6.28, p < .001, η2 = .264. A Tukey’s honestly significant difference test showed that over- all performance by subjects in the positive-mood condition (M = .85) was higher than performance by subjects in the neg- ative-mood condition (M = .73, p < .0001) and subjects in the neutral-mood condition (M = .73, p < .0001). Performance did not differ between subjects in the neutral- and negative-mood conditions (p = .69). No effect of mood on overall perfor- mance was found for the II category set (p = .71). Overall pro- portions correct were as follows—positive-mood condition: .64; negative-mood condition: .66; and neutral-mood condi- tion: .64. Computational modeling For insight into the response strategies used by our subjects, we fit decision-bound models to the first block of each sub- ject’s data (for details, see Ashby, 1992a; Maddox & Ashby, 1993). We analyzed the first block of trials because that is when mood-induction effects are likely to be strongest, and it is also when cognitive flexibility is most needed. One class of models assumed that each subject’s performance was based on a single-dimensional rule (we used an optimal version with a fixed intercept and a version with the intercept as a free param- eter). Another class of models assumed that each subject’s per- formance was based on the two-dimensional II boundary (we

- 13. used an optimal version with a fixed intercept and slope, a ver- sion with a fixed slope, and a version with a freely varying P ro po rt io n C or re ct RD Category Set II Category Set .0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1.0 P ro po

- 14. rt io n C or re ct .0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1.0 Block Block Positive Mood Neutral Mood Negative Mood Positive Mood Neutral Mood Negative Mood 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 Fig. 2. Average proportion of correct responses to stimuli in the three mood conditions as a function of trial block. Subjects were tested on either the

- 15. rule-described (RD) category set (left graph) or the non-RD, information-integration (II) category set (right graph). Error bars denote standard errors of the mean. 1774 Nadler et al. slope and intercept). We fit these models to each subject’s data by maximizing the log likelihood. Model comparisons were carried out using Akaike’s information criterion, which penal- izes a model for the number of free parameters (Ashby, 1992b). The proportion of subjects whose responses were best fit by their respective optimal model is shown in Figure 3. For the RD categories, .83 of positive-mood subjects, .62 of neutral- mood subjects, and .54 of negative-mood subjects were fit best by a model that assumed a single-dimensional rule. For the II categories, .71 of positive-mood subjects, .40 of neutral-mood subjects, and .43 of negative-mood subjects were fit best by one of the II models. Discussion In this experiment, positive, neutral, and negative moods were induced before subjects learned either an RD or a non-RD, II category set. The RD set required subjects to use hypothesis testing, rule selection, and response inhibition to achieve opti- mal performance, and the II set was best learned by associat- ing regions of perceptual space with responses (Ashby & Gott, 1988). We found that positive mood enhanced RD learning com- pared with neutral and negative moods. Mood did not seem to affect II learning. However, a comparison of decision-bound models suggested that positive-mood subjects displayed a greater degree of cognitive flexibility compared with neutral- and negative-mood subjects by adopting an optimal strategy

- 16. early in both RD and II learning. The COVIS theory suggests that people learn categories using an explicit, rule-based system or an implicit, similarity- based system (Ashby et al., 1998; Ashby & Maddox, 2005; Minda & Miles, 2010). The brain areas that mediate these sys- tems have been well studied, linking the PFC, ACC, and medial temporal lobes to the explicit system but not to the implicit system. Our experiment highlights a variable that facilitates the learning of RD categories using the explicit system. The finding that positive mood enhances performance of the explicit system posited by the COVIS theory corresponds with the dopamine hypothesis of positive affect (Ashby et al., 1999). Our results connect this research with existing work on category learning, and we view this connection as a substan- tial step forward in the study of cognition and mood. We sus- pect that our positive-mood subjects experienced increased cognitive flexibility, which allowed them to find the optimal verbal rule faster than negative-mood subjects and neutral- mood subjects did. Performance on the II category set did not differ strongly across the different mood conditions. This result is also in line with the dopamine hypothesis, as positive mood is not theorized to affect the same brain regions P ro po rt io n F

- 18. it by O pt im al M od el .0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1.0 Positive Neutral Negative Mood-Induction Condition Positive Neutral Negative Mood-Induction Condition RD Category Set II Category Set

- 19. Fig. 3. Proportion of subjects in each mood-induction condition whose responses best fit the optimal model for the category set to which they were assigned. Subjects learned either the rule-described (RD) category set (left graph) or the non-RD, information-integration (II) category set (right graph). Better Mood and Better Performance 1775 hypothesized by the COVIS theory to be involved with the learning of non-RD category sets. However, our modeling results suggest that the cognitive flexibility associated with positive mood may affect the strategies used in II category learning. This cognitive flexibility could allow the explicit system to exhaust rule searches more effectively, even though performance levels may remain unchanged between the conditions. We failed to find an effect of negative mood in RD learn- ing. This is in line with previous research that reported no dif- ferences between negative- and neutral-mood subjects on measures of cognitive flexibility (Isen, Daubman, & Nowicki, 1987). It may be that negative mood does not affect RD cate- gory learning, although we think it could, given the right cir- cumstances. One possible explanation of why we did not find such an effect is that the induced negative mood may not have been sustained long enough to interfere with performance. We suspect that subjects in certain negative states will be impaired in RD category learning. Future work should examine ways of sustaining mood states and should explore a wider range of negative mood states. An intriguing possibility that was not observed is that nega-

- 20. tive mood could enhance II category learning. Recent research suggests that affective states low in motivational intensity (e.g., amusement, sadness) are associated with broadened attention, and affective states high in motivational intensity (e.g., desire, disgust) are associated with narrowed attention (Gable & Harmon-Jones, 2008, 2010). Thus, for example, sad- ness may facilitate performance when broadened attention is beneficial for category learning. We did not find this effect, either because learning of the II category set used did not ben- efit from broadened attention or because the induced negative mood was high in motivational intensity. These interesting ideas require further research. Smith et al. (1993) showed that clinically depressed sub- jects were impaired in RD category learning and unimpaired in II category learning, but our research is the first to investi- gate how experimentally induced mood states influence cate- gory learning. We have shown that positive mood enhanced the learning of an RD category set, an advantage that was strong and sustained throughout the task. Positive mood did not improve the learning of II categories, though there was evidence that positive mood enhanced selection of the optimal strategy. By connecting theories of multiple-system category learning and positive affect, our research suggests that positive affect enhances performance when category learning benefits from cognitive flexibility. Future work should examine the interaction between mood states (motivationally weak com- pared with intense), valence (positive compared with nega- tive), and category type (explicit compared with implicit) in category learning. Acknowledgments We thank E. Hayden for many valuable insights on this project. Declaration of Conflicting Interests

- 21. The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article. Funding This research was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Grant R3507A03 to J.P.M., an Ontario Graduate Scholarship award to R.T.N., and an NSERC fellowship to R.R. Notes 1. We define cognitive flexibility as the ability to seek out and apply alternate strategies to problems (Maddox, Baldwin, & Markman, 2006) and to find unusual relationships between items (Isen, Johnson, Mertz, & Robinson, 1985). 2. The clips can be found by searching for their titles on YouTube (http://www.youtube.com/), or URLs can be obtained from the first author. 3. Stimulus parameters and generation were the same as those used by Zeithamova and Maddox (2006). References Ashby, F.G. (1992a). Multidimensional models of categorization. In F.G. Ashby (Ed.), Multidimensional models of perception and

- 22. cognition (pp. 449–483). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Ashby, F.G. (1992b). Multivariate probability distributions. In F.G. Ashby (Ed.), Multidimensional models of perception and cogni- tion (pp. 1–34). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Ashby, F.G., Alfonso-Reese, L.A., Turken, A.U., & Waldron, E.M. (1998). A neuropsychological theory of multiple systems in cat- egory learning. Psychological Review, 105, 442–481. Ashby, F.G., & Ell, S.W. (2001). The neurobiology of human cat- egory learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5, 204–210. Ashby, F.G., & Gott, R. (1988). Decision rules in the perception and categorization of multidimensional stimuli. Journal of Experimen- tal Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 14, 33–53. Ashby, F.G., Isen, A.M., & Turken, A.U. (1999). A neuropsychologi- cal theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psy- chological Review, 106, 529–550. Ashby, F.G., & Maddox, W.T. (2005). Human category learning. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 149–178. Gable, P., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2008). Approach-motivated positive affect reduces breadth of attention. Psychological Science, 19, 476–482.

- 23. Gable, P., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2010). The blues broaden, but the nasty narrows. Psychological Science, 21, 211–215. Isen, A.M. (1990). The influence of positive and negative affect on cognitive organization: Some implications for development. In N.L. Stein, B. Leventhal, & T.R. Trabasso (Eds.), Psychological and biological approaches to emotion (pp. 75–94). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Isen, A.M. (1999). On the relationship between affect and creative problem solving. In S.W. Russ (Ed.), Affect, creative experience, 1776 Nadler et al. and psychological adjustment (pp. 3–17). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis. Isen, A.M., Daubman, K.A., & Nowicki, G.P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1122–1131. Isen, A.M., Johnson, M.M.S., Mertz, E., & Robinson, G.F. (1985). The influence of positive affect on the unusualness of word associations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1413–1426. Maddox, W.T., & Ashby, F.G. (1993). Comparing decision

- 24. bound and exemplar models of categorization. Perception & Psychophysics, 53, 49–70. Maddox, W.T., & Ashby, F.G. (2004). Dissociating explicit and pro- cedural-learning based systems of perceptual category learning. Behavioral Processes, 66, 309–332. Maddox, W.T., Ashby, F.G., Ing, A.D., & Pickering, A.D. (2004). Disrupting feedback processing interferes with rule-based but not information-integration category learning. Memory & Cognition, 32, 582–591. Maddox, W.T., Baldwin, G., & Markman, A. (2006). A test of the regulatory fit hypothesis in perceptual classification learning. Memory & Cognition, 34, 1377–1397. Minda, J.P., & Miles, S. (2010). The influence of verbal and nonver- bal processing on category learning. In B. Ross (Ed.), The psy- chology of learning and motivation (pp. 117–162). Burlington, VT: Academic Press. Mitchell, R., & Phillips, L. (2007). The psychological, neurochemi- cal and functional neuroanatomical mediators of the effects of positive and negative mood on executive functions. Neuropsy- chologia, 45, 617–629. Nomura, E.M., Maddox, W.T., Filoteo, J.V., Ing, A.D.,

- 25. Gitelman, D.R., Parrish, T.B., et al. (2007). Neural correlates of rule- based and information-integration visual category learning. Cerebral Cortex, 17, 37–43. Pierce, J. (2007). PsychoPy—psychophysics software in Python. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 162, 8–13. Smith, J.D., Tracy, J.I., & Murray, M.J. (1993). Depression and cat- egory learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 122, 331–346. Watson, D., Clark, L., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. Zeithamova, D., & Maddox, W. (2006). Dual-task interference in per- ceptual category learning. Memory & Cognition, 34, 387–398. Running head: DO WEAPONS MAKE PEOPLE AGGRESSIVE? 1 DO WEAPONS MAKE PEOPLE AGGRESSIVE 7 Weapons as Aggression-Eliciting Stimuli Jane Doe Florida International University Weapons as Aggression-Eliciting Stimuli

- 26. Summary: Berkowitz and Lepage (1967) designed a study to test the hypothesis that individuals who are in a state of anger are more likely to act out their aggression if cues associated with violence and aggression are present. The sample consisted of 100 male students from the University of Wisconsin who were all enrolled in an introductory level psychology course. This study used an experimental research method because it manipulated the independent variable and presumably involved random assignment (although this was not stated in the text). There were two main independent variables. The first one was the subject’s level of anger and this was determined by whether the subject was shocked once or seven times. The second independent variable was the kind of cue present near the shock button when it was the subject’s turn to evaluate the confederate. For one group there was no object, in the control group there was a neutral object (a badminton racquet), and for the last group there was a gun that was supposedly part of a different study. This last group was further separated into 2 subgroups with some being told that the gun belonged to the confederate while others were told that it was left behind by someone else. These independent variables were then combined to see how they affected the dependent variable, which was the level of aggression the subject displayed. The dependent variable was measured by how many shocks the subject delivered to the confederate. The procedure ran as follows: volunteers were told that they were participating in a study to test the physiological effects of stress. To do this the subject and the other participant (who was actually a confederate) were both given a social problem and they had to think up ways to solve it. After they completed this task (in separate rooms) their problem solving ideas were then exchanged so they could evaluate each other. The evaluation was done by pushing a button that was supposed to shock the person in the other room (although they still could not see each other); 1 shock represented the best rating while a

- 27. lesser evaluation was communicated through a higher number of shocks. The confederate was the first to do the evaluation. The number of shocks given to the actual volunteer was already determined as 1 or 7 though (depending on the random assignment) and was not based on a real rating. After this came the volunteer’s turn to do the same evaluation, but the number of shocks was not predetermined. Next to the shock button was one of the previously stated objects, and the gun was the only cue hypothesized to elicit increased aggression. The results of this study confirmed the hypothesis. Those participants who were more angered (given 7 shocks) and were cued by the violent object (a gun) and told that it belonged to the person they were rating, outwardly expressed their aggression the most by giving the confederate a higher number of shocks. The next highest number of shocks was by the group in the presence of a gun, but had been told the gun was left behind by someone else. Those who did not see any objects gave on average one less shock and the least number of shocks were given by those in the presence of the badminton racquets. On the other hand, when the volunteer was not as angered (only shocked once by the confederate), outward expression of aggression was relatively low and stable regardless of what type of cue was present. The researchers used these results to theorize that a person who is already aroused and is then cued by a violent object is more likely to have an impulsive reaction to act more aggressively. Critique: Overall this study was well designed in order to test the given hypothesis that weapons are aggression-eliciting stimuli. The method of using different objects to induce a given response is very similar to the proven phenomenon of priming. Priming is where certain information is more attended to when related cues are presented. Therefore the results of Berkowitz and Lepage (1967) make sense because weapons are connected to

- 28. aggression, which increases the person’s awareness of his or her aggressive feelings, and consequently makes the outward act of aggression more likely. Based on the results, chances are high that these men would always act in this way when in a similar situation, so this study can be considered reliable (that is, it is repeatable). Validity is not as strong, though. Validity refers to whether the study is measuring what it purports to measure. When the participant was already aroused (given 7 shocks) there was a significant difference in the amount of retaliation depending on which cue was present. However, this retaliation did not depend on the cues if the participant was not as initially aroused (only given 1 shock). So how can they be measuring the impact of a priming mechanism like the gun in the room if they need participants to already be aroused? I am not sure they are measuring their variables correctly. That being said, it did show that although the cues do have an effect on aggressive behavior, initial aggression level plays a much larger role in the causal relationship. The ethicalness of this study is also questionable. Receiving and delivering shocks could potentially cause physical pain and also have a negative effect on one’s emotional well-being. Nonetheless, most participants probably did not suffer any serious consequences. Also, due to the nature of this specific research question it does not seem like there is another way to measure aggression that would be anymore ethical. One major methodological problem that should have been addressed is the sample that was obtained. The sample used in this experiment is not a good representation of humans in general, because it only involved college-aged men. It is possible that women or people of different ages may respond differently to the cues. Women are often thought of as less violent, so their reaction to a negative stimulus might cause them to deliver fewer shocks. A weapon makes the seriousness of the situation salient and may cause some people to think rationally about their behavior in the near future. Clearly this proposal requires actual testing before making further

- 29. assumptions, but it does show the need for a more diverse sample of participants. Along the same line as the previous issue, a follow-up study could more carefully look at the relationship between peoples’ attitudes towards guns (or other weapons) and their corresponding level of aggressive behavior when given the chance to retaliate. This would be more of a quasi-experiment because in order to test the independent variable of attitudes towards weapons the groups could not be randomly assigned. Three existing groups would be used; those who support weapons, those who are against them, and those who feel neutral (the control group). The hypothesis would predict that if prior arousal level was high, participants who support weapons would show increased aggression when cued by the gun, but the group of participants with negative attitudes towards guns would not be as aggressive. If the subjects did not receive prior arousal (if they were only shocked once by their “evaluator”), then neither group would be significantly affected by the cues. Even if initial aggression is a greater cause in inducing violent behavior than the existence of weapon-related cues, this study has serious implications for social policies related to gun control. It is apparent from the results that if someone is angry and is near a gun, then that person will likely act more aggressively than he or she typically would. Since the guns in the experiment were not loaded and the situation was controlled, the heightened aggression was not transferred over to actually using the guns. In a private home though, arguments occurring with a gun nearby might make it more likely that a gun will be used. Knowing that the mere presence of a weapon increases violence should urge lawmakers to consider adopting stricter gun laws. Brief summary Berkowitz and Lepage (1967) conducted a study in which they

- 30. hypothesized that priming people with an aggressive object (a gun) would lead them to act aggressively. The authors gave electrical shocks (from 1 to 7 of them) to 100 male undergraduates. They told them that one of their peers had delivered the shock. The participant could then retaliate, but they did so in the presence of either a gun or a tennis racket (which was supposedly left in the researcher room from a different study). Participants given the highest number of shocks (7) gave higher retaliation shocks to the peer, but this was more likely when they were in the presence of a gun (compared to a tennis racket). The authors concluded that the guns increased aggressive responses from male participants who were highly aroused. References Berkowitz, L., & Lepage, A. (1967). Weapons as aggression- eliciting stimuli. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7, 202-207. doi: 10.1037/h0025008 Running head: ARTICLE CRITIQUE INSTRUCTIONS 1 ARTICLE CRITIQUE INSTRUCTIONS 2 Article Critique Instructions (60 points possible) Ryan J. Winter Florida International University

- 31. Purpose of The Article Critique Paper 1). Psychological Purpose This paper serves several purposes, the first of which is helping you gain insight into research papers in psychology. As this may be your first time reading and writing papers in psychology, one goal of Paper I is to give you insight into what goes into such papers. This article critique paper will help you learn about the various sections of an empirical research report by reading at least one peer-reviewed articles (articles that have a Title Page, Abstract*, Literature Review, Methods Section, Results Section, and References Page—I have already selected some articles for you to critique, so make sure you only critique one in the folder provided on Canvas) This paper will also give you some insights into how the results sections are written in APA formatted research articles. Pay close attention to those sections, as throughout this course you’ll be writing up some results of your own! In this relatively short paper, you will read one of five articles posted on Canvas and summarize what the authors did and what they found. The first part of the paper should focus on summarizing the design the authors used for their project. That is, you will identify the independent and dependent variables, talk about how the authors carried out their study, and then summarize the results (you don’t need to fully understand the statistics in the results, but try to get a sense of what the authors did in their analyses). In the second part of the paper, you will critique the article for its methodological strengths and weaknesses. Finally, in part three, you will provide your references for the Article Critique Paper in APA format. 2). APA Formatting Purpose The second purpose of the Article Critique paper is to teach you proper American Psychological Association (APA) formatting. In the instructions below, I tell you how to format your paper using APA style. There are a lot of very specific requirements in APA papers, so pay attention to the instructions below as well as Chapter 14 in your textbook! I highly recommend using

- 32. the Paper I Checklist before submitting your paper, as it will help walk you through the picky nuances of APA formatting. 3). Writing Purpose Finally, this paper is intended to help you grow as a writer. Few psychology classes give you the chance to write papers and receive feedback on your work. This class will! We will give you feedback on this paper in terms of content, spelling, and grammar. Article Critique Paper (60 points possible) Each student is required to write an article critique paper based on one of the research articles present on Canvas only those articles listed on Canvas can be critiqued – if you critique a different article, it will not be graded). If you are unclear about any of this information, please ask. What is an article critique paper? An article critique is a written communication that conveys your understanding of a research article and how it relates to the conceptual issues of interest to this course. This article critique paper will include 5 things: 1. Title page: 1 page (4 points) · Use APA style to present the appropriate information: · A Running head must be included and formatted APA style · The phrase “Running head” is at the top of the title page followed by a short title of your creation (no more than 50 characters) that is in ALL CAPS. This running head is left- justified (flush left on the page). Note that the “h” in head is all lower case! Look at the first page of these instructions, and you will see how to set up your Running head. · There must be a page number on the title page that is right justified. It is included in the header

- 33. · Your paper title appears on the title page. This is usually 12 words or less, and the first letter of each word is capitalized. It should be descriptive of the paper (For this paper, you should use the title of the article you are critiquing. The paper title can be the same title as in the Running head or it can differ – your choice) · Your name will appear on the title page · Your institution will appear on the title page as well · For all papers, make sure to double-space EVERYTHING and use Times New Roman font. This includes everything from the title page through the references. · This is standard APA format. ALL of your future papers will include a similar title page 2. Summary of the Article: 1 ½ page minimum, 3 pages maximum - 14 points) An article critique should briefly summarize, in your own words, the article research question and how it was addressed in the article. Below are some things to include in your summary. · The summary itself will include the following: (Note – if the article involved more than one experiment, you can either choose to focus on one of the studies specifically or summarize the general design for all of the studies) 1. Type of study (Was it experimental or correlational? How do you know?) 2. Variables (What were the independent and dependent variables? How did they manipulate the IV? How did they operationally define the DV? Be specific with these. Define the terms independent and dependent variable and make sure to identify how they are operationally defined in the article) 3. Method (What did the participants do in the study? How was it set up? Was there a random sample of participants? Was there random assignment to groups?). How was data collected (online, in person, in a laboratory?). 4. Summary of findings (What were their findings?) · Make sure that:

- 34. 1. The CAPS portion of your running head should also appear on the first page of your paper, but it will NOT include the phrase “Running head” this time, only the same title as the running head from the first paper in ALL CAPS. Again, see the example paper. There is a powerpoint presentation on using Microsoft Word that can help you figure out how to have a different header on the title page (where “Running head” is present) and other pages in the paper (where “Running head” is NOT present). You can also find how-to information like this using youtube! 2. If you look at the header in pages 2 through 5 (including THIS current page 4 that you are reading right now!), you will see “Running head” omitted. It simply has the short title (ARTICLE CRITIQUE PAPER INSTRUCTIONS) all in caps, followed by the page number. 3. The same title used on the title page should be at the top of the page on the first actual line of the paper, centered. 4. For this paper, add the word “Summary” below the title, and have it flush left. Then write your summary of the article below that. 3. Critique of the study: 1 ½ pages minimum - 3 pages maximum - 16 points) 1. This portion of the article critique assignment focuses on your own thoughts about the content of the article (i.e. your own ideas in your own words). For this section, please use the word “Critique” below the last sentence in your summary, and have the word “Critique” flush left. 1. This section is a bit harder, but there are a number of ways to demonstrate critical thinking in your writing. Address at least four of the following elements. You can address more than four, but four is the minimum. · 1). In your opinion, are there any confounding variables in the study (these could be extraneous variables or nuisance variables)? If so, explain what the confound is and specifically

- 35. how it is impacting the results of the study. A sufficient explanation of this will include at least one paragraph of writing. · 2). Is the sample used in the study an appropriate sample? Is the sample representative of the population? Could the study be replicated if it were done again? Why or why not? · 3). Did they measure the dependent variable in a way that is valid? Be sure to explain what validity is, and why you believe the dependent variable was or was not measured in a way that was valid. · 4). Did the study authors correctly interpret their findings, or are there any alternative interpretations you can think of? · 5). Did the authors of the study employ appropriate ethical safeguards? · 6). Briefly describe a follow-up study you might design that builds on the findings of the study you read how the research presented in the article relates to research, articles or material covered in other sections of the course · 7). Describe whether you feel the results presented in the article are weaker or stronger than the authors claim (and why); or discuss alternative interpretations of the results (i.e. something not mentioned by the authors) and/or what research might provide a test between the proposed and alternate interpretations · 8). Mention additional implications of the findings not mentioned in the article (either theoretical or practical/applied) · 9). Identify specific problems in the theory, discussion or empirical research presented in the article and how these problems could be corrected. If the problems you discuss are methodological in nature, then they must be issues that are substantial enough to affect the interpretations of the findings or arguments presented in the article. Furthermore, for methodological problems, you must justify not only why something is problematic but also how it could be resolved and why your proposed solution would be preferable. · 10). Describe how/why the method used in the article is either

- 36. better or worse for addressing a particular issue than other methods 4. Brief summary of the article: One or paragraphs (6 points) · Write the words “Brief Summary”, and then begin the brief summary below this · In ONE or TWO paragraphs maximum, summarize the article again, but this time I want it to be very short. In other words, take all of the information that you talked about in the summary portion of this assignment and write it again, but this time in only a few sentences. · The reason for this section is that I want to make sure you can understand the whole study but that you can also write about it in a shorter paragraph that still emphasizes the main points of the article. Pretend that you are writing your own literature review for a research study, and you need to get the gist of an article that you read that helps support your own research across to your reader. Make sure to cite the original study (the article you are critiquing). 5. References – 1 page (4 points) · Provide the reference for this article in proper APA format (see the book Chapter 14 for appropriate referencing guidelines or the Chapter 14 powerpoint). · If you cited other sources during either your critique or summary, reference them as well (though you do not need to cite other sources in this assignment – this is merely optional IF you happen to bring in other sources). Formatting counts here, so make sure to italicize where appropriate and watch which words you are capitalizing! 6. Grammar and Writing Quality (6 points) · Few psychology courses are as writing intensive as Research Methods (especially Research Methods Two next semester!). As such, I want to make sure that you develop writing skills early. This is something that needs special attention, so make sure to

- 37. proofread your papers carefully. · Avoid run-on sentences, sentence fragments, spelling errors, and grammar errors. Writing quality will become more important in future papers, but this is where you should start to hone your writing skills. · We will give you feedback on your papers, but I recommend seeking some help from the FIU writing center to make sure your paper is clear, precise, and covers all needed material. I also recommend asking a few of your group members to read over your paper and make suggestions. You can do the same for them! · If your paper lacks originality and contains too much overlap with the paper you are summarizing (i.e. you do not paraphrase appropriately or cite your sources properly), you will lose some or all of the points from writing quality, depending on the extent of the overlap with the paper. For example, if sentences contain only one or two words changed from a sentence in the original paper, you will lose points from writing quality. Please note that you do not need to refer to any other sources other than the article on which you have chosen to write your paper. However, you are welcome to refer to additional sources if you choose. 7. Self-Rating Rubric (10 points). On canvas, you will find a self-rating rubric. This rubric contains a summary of all the points available to you in this paper. You must submit your ratings for your own paper, using this rubric (essentially, you’ll grade your own paper before you hand it in). You will upload your completed rubric to the “article critique rubric” assignment on Canvas. · Please put effort into your ratings. Do not simply give yourself a 50/50. Really reflect on the quality of your paper and whether you meet all the criteria listed. 1. If it is clear that you have not reflected sufficiently on your paper (e.g., you give a rating of 2/2 for something that is not

- 38. included in your paper), you will lose points. · This does not mean that you are guaranteed whatever grade you give to yourself. Instead, this will help you to 1) make sure that you have included everything you need to include, and 2) help you to reflect on your own writing. · In fact, we will use this very same rubric when we grade your paper, so you should know exactly what to expect for your grade! Other guidelines for the article critique papers 1. 1). Pay attention to the page length requirements – 1 page for the title page, 1.5 pages to 3 pages for the summary, 1.5 pages to 3 pages for the critique, one or two paragraphs for the brief summary, and 1 page for the references page. If you are under the minimum, we will deduct points. If you go over the maximum, we are a little more flexible (you can go over by half page or so), but we want you to try to keep it to the maximum page. 1. 2). Page size is 8 1/2 X 11” with all 4 margins set one inch on all sides. You must use 12-point Times New Roman font. 1. 3). As a general rule, ALL paragraphs and sentences are double spaced in APA papers. It even includes the references, so make sure to double space EVERYTHING 1. 4). When summarizing the article in your own words, you need not continually cite the article throughout the rest of your critique. Nonetheless, you should follow proper referencing procedures, which means that: 3. If you are inserting a direct quote from any source, it must be enclosed in quotations and followed by a parenthetical reference to the source. “Let’s say I am directly quoting this current sentence and the next. I would then cite it with the author name, date of publication, and the page number for the direct quote” (Winter, 2013, p . 4). 0. Note: We will deduct points if you quote more than once per page, so keep quotes to a minimum. Paraphrase instead, but

- 39. make sure you still give the original author credit for the material by citing him or using the author’s name (“In this article, Smith noted that …” or “In this article, the authors noted that…”) 3. If you choose to reference any source other than your chosen article, it must be listed in a reference list. 1. 5). Proofread everything you write. I actually recommend reading some sentences aloud to see if they flow well, or getting family or friends to read your work. Writing quality will become more important in future papers, so you should start working on that now! If you have any questions about the articles, your ideas, or your writing, please ask. Although we won’t be able to review entire drafts of papers before they are handed in, we are very willing to discuss problems, concerns or issues that you might have.