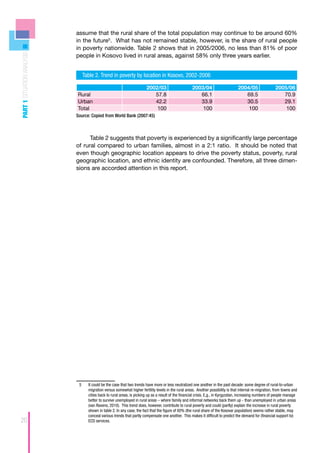

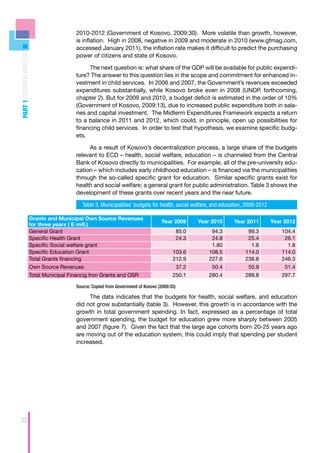

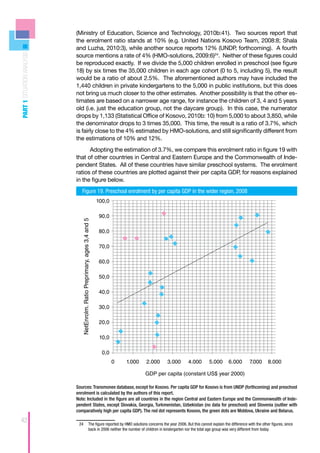

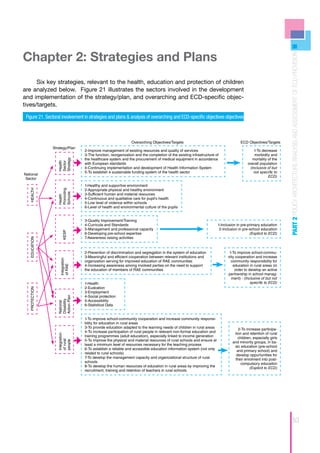

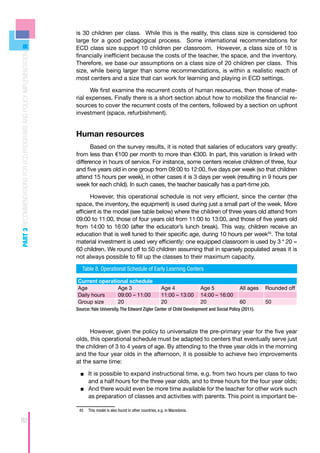

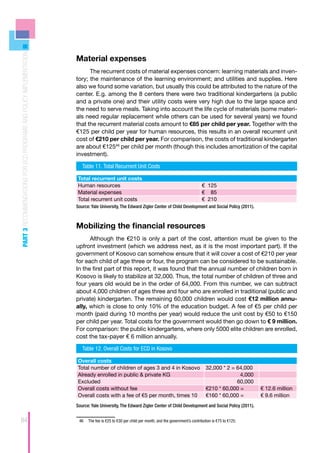

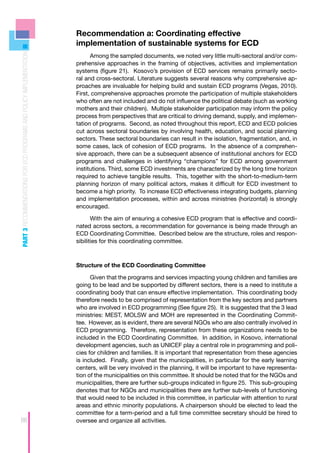

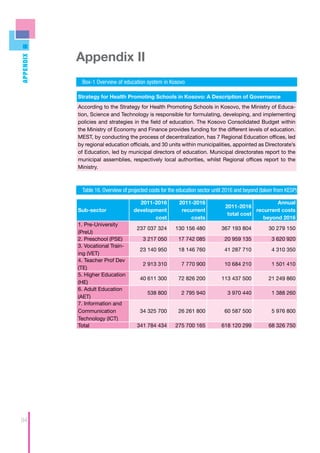

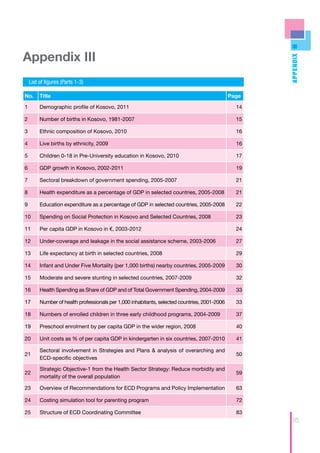

This report analyzes early childhood development (ECD) programs and policies in Kosovo, highlighting the need for better support for young children and their families. It identifies gaps in services, especially for disadvantaged groups, and recommends strategies to enhance ECD through improved governance and targeted programs. The findings and recommendations aim to inform the creation of a sustainable ECD framework that addresses the rights and needs of all children up to six years old.