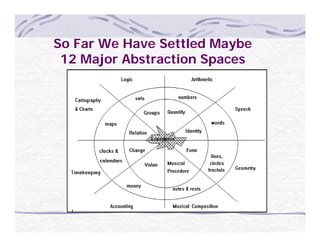

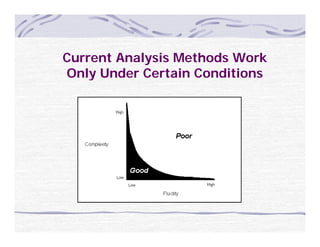

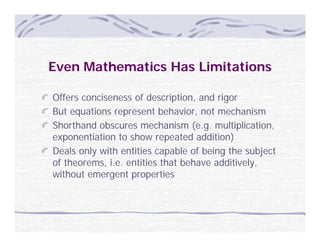

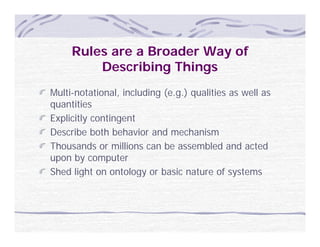

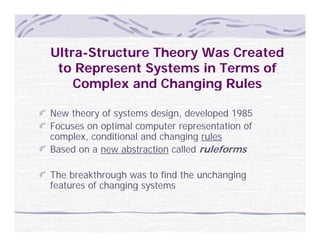

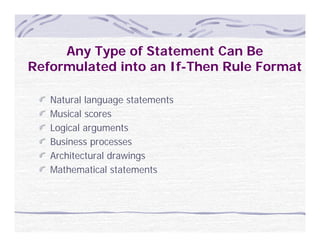

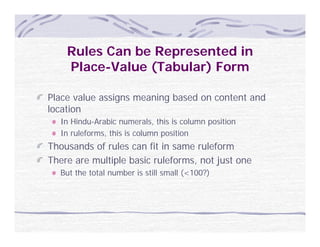

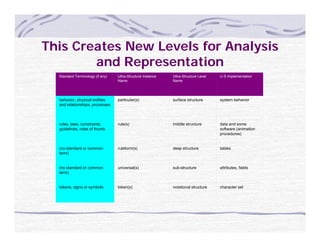

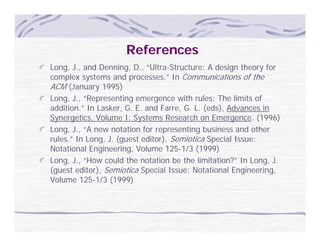

Jeffrey G. Long's document explores the challenges of understanding complex systems, arguing that perceived complexity is often due to inadequate notational systems rather than the systems themselves. He introduces concepts like 'notational engineering' and 'ultra-structure' to propose new ways to represent and analyze complex rules governing system behavior. The paper emphasizes the importance of developing new abstractions to improve our understanding of complex phenomena across various fields.