This document discusses accelerating decarbonization through trade in climate goods and services. It provides context on how trade can help spread climate-friendly technologies and presents lists of proposed climate goods and services that trade policymakers could prioritize to help reduce emissions. Specifically, it identifies 25 key climate technologies across energy, transport, buildings and other sectors that have significant emissions reduction potential. It also discusses challenges like non-tariff barriers and the needs of developing countries to be included in climate trade discussions and benefit from opportunities in green growth and jobs. The report aims to support efforts among governments to collaborate more on liberalizing trade related to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

![20. McKinsey, Climate math: What a 1.5-degree pathway would take, 2020.

21. International Energy Agency (IEA), Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, 2021.

22. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and World Bank Group, The unseen impact of non-tariff

measures, 2018, https://unctad.org/webflyer/unseen-impact-non-tariff-measures-insights-new-database.

23. De Melo, Jaime and Jean-Marc Solleder, “The role of an Environmental Goods Agreement in the quest to improve the

regime complex for Climate Change”, EUI Working Paper, 2019.

24. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Business Perceptions of Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs)

Facing Trade in Selected Environmental Goods and Associated Services: Survey Results, COM/ENV/TD(2006)48/FINAL,

2007.

25. Monkelbaan, J., Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment on the Environmental Goods Agreement, EU publications, 2016.

26. UNCTAD, International Classification of Non-tariff Measures, 2019; The International Classification of non-tariff measures

(NTMs) follows a taxonomy of all measures considered relevant in today’s international trade. It comprises technical

measures and other measures traditionally used as instruments of commercial policy, e.g. quotas, price control, exports

restrictions or contingent trade protective measures. Finally, the international classification of NTMs also comprises

behind-the-border measures, such as competition, trade-related investment measures, government procurement or

distribution restrictions. This classification is determined by a group of eight international organizations, including the

International Monetary Fund (IMF), the OECD, the World Bank and the WTO.

27. “How do Technical Barriers to Trade impact trade in environmental goods”, UK Department for International Trade,

19 July 2022.

28. International Energy Agency, Test Procedures and Quality Labels for Heat Pump Water Heaters, 2019,

https://heatpumpingtechnologies.org/annex46/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2020/10/hpt-an46-05-task-1-test-

procedures-and-quality-labels-for-heat-pump-water-heaters.pdf.

29. World Economic Forum, Delivering a Climate Trade Agenda: Industry Insights, 2021, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/

WEF_Delivering_a_Climate_Trade_Agenda_2021.pdf.

30. OECD, Overcoming Barriers to International Investment in Clean Energy, Green Finance and Investment, 2015.

31. WTO, Services Sectoral Classification List, 1991, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/mtn_gns_w_120_e.doc.

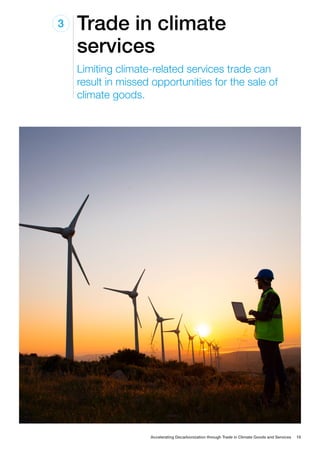

32. In a joint proposal tabled already in 2007 under Paragraph 31(iii) of the Doha Declaration, the United States and

European Union argued that services that enabled members to fulfil climate change-related objectives included not only

environmental services (such as air pollution control and climate control services), but also technical testing and analysis

services (e.g. air composition and purity testing services), energy-related services (e.g. engineering and maintenance

services to optimize the environmental performance of energy facilities), and services for the design and construction of

energy-efficient buildings and facilities. Proposal for a Result under Paragraph 31(iii) of the Doha Ministerial Declaration,

non-paper by the European Union and the United States (JOB(07)/193/rev.1), 2007.

33. See Committee on Specific Commitments, “Services related to climate change”, Informal Note by the WTO Secretariat

(JOB/SERV/100), 2012.

34. Steenblik, R. and M. Geloso Grosso, Trade in Services Related to Climate Change: An Exploratory Analysis, OECD, 2011.

35. National Board of Trade Sweden, Trade and Climate Change Promoting climate goals with a WTO agreement, 2021.

36. Kim, J. A., Facilitating Trade in Services Complementary to Climate-friendly Technologies, ICTSD, 2011.

37. For example, Monkelbaan, J., Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment on the Environmental Goods Agreement, EU

publications, 2016; Sauvage, J. and C. Timiliotis, Trade in services related to the environment, OECD, 2017.

38. OECD.Stat, Services Trade Restrictiveness Index [Table], https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=STRI.

39. WTO, WTO members engage in exploratory talks on market access for environmental services [Press release], 30

September 2019.

40. de Melo, Jaime, and Mariana Vijil, “The Critical Mass Approach to Achieve a Deal on Green Goods and Services: What is

on the Table? How Much to Expect?” FEEM Working Paper No. 070.2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2486445.

41. International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD), “Enabling the Energy Transition and Scale-Up of

Clean Energy Technologies: Options for the Global Trade System”, E15 Expert Group on Clean Energy Technologies and

the Trade System, Policy Options Paper, 2016.

42. Geloso Grosso, M., Trade and Regulation: The Case of Construction Services, OECD, 2008.

43. See for example: “Environmental Insights Explorer”, Google, n.d. https://insights.sustainability.google/.

44. While the amount of computing done in global data centres increased by about 550% between 2010 and 2018,

the amount of energy consumed by data centres grew by only 6% during the same period. See Masanet E., et al.,

“Recalibrating global data center energy-use estimates”, Science, vol. 367, no. 6481, 2020.

45. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), South-South Trade in Renewable Energy: A Trade Flow Analysis of

Selected Environmental Goods, 2014.

46. Ibid.

47. Brenton, P. and V. Chemutai, The Trade and Climate Change Nexus: The Urgency and Opportunities for Developing

Countries, World Bank Group, 2021, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36294.

Accelerating Decarbonization through Trade in Climate Goods and Services 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wefacceleratingdecarbonizationthroughtrade2022-240112130035-50c36cc7/85/WEF-Accelerating-Decarbonization-through-Trade-2022-30-320.jpg)

![48. Teehankee, M., Trade and Environment Governance at the World Trade Organization Committee on Trade and Environment,

Kluwer Law International, 2020.

49. Monkelbaan, J., M. Sugathan and A. Naranjo, Environmental Goods and Services: Questions and Possible Ways Forward

in the TESSD, Working Paper No. 2 in Trade and Environmental Sustainability Series, Quaker United Nations Office, 2021.

50. For example, building a concentrated solar power system requires materials such as steel, copper, silica and molten salt,

as well as components such as collectors, mirrors, reflector film, steam generators, heat collection elements, heat storage

and central control systems.

51. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Renewable Energy Jobs Continue Growth to 11.5 Million Worldwide

[Press release], 29 September 2020.

52. Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), Natural Resources Defence Coucil (NRDC), Laying the Foundation for

a Bright Future: Assessing Progress Under Phase 1 of India’s National Solar Mission, 2012.

53. Trade and Environment, Kluwer Law International, 2020.

54. UNCTAD and the World Bank, The unseen impact of non-tariff measures, 2018, https://unctad.org/webflyer/unseen-

impact-non-tariff-measures-insights-new-database.

55. Wu, Mark, “Why Developing Countries Won’t Negotiate: The Case of the WTO Environmental Goods Agreement”, Trade,

Law, and Development, vol. 6, no. 1, 2014, pp. 93-176.

56. Cosbey, Aaron, Breathing Life into the List: Practical Suggestions for the Negotiators of the Environmental Goods

Agreement, FES, 2015.

57. Sugathan, Mahesh, Mutual Recognition Agreement on Conformity Assessment: A Deliverable on Non-Tariff Measures for

the EGA?, ICTSD, 2016.

Accelerating Decarbonization through Trade in Climate Goods and Services 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wefacceleratingdecarbonizationthroughtrade2022-240112130035-50c36cc7/85/WEF-Accelerating-Decarbonization-through-Trade-2022-31-320.jpg)