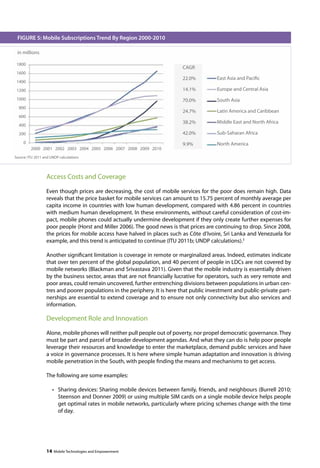

This document provides an overview of how mobile technologies can enhance human development through participation and innovation. It discusses current mobile subscription trends, noting that over 5 billion subscriptions globally demonstrates that ICT access targets may be achievable by 2015. It also outlines how mobile technologies are starting to impact areas like democratic governance, poverty reduction, and crisis response. The document aims to help UNDP staff understand how to leverage mobile technologies to strengthen development programming and outcomes.