The document provides recommendations for conducting oral reading assessments based on a collaborative project led by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. It discusses key principles that should be applied in planning, designing, implementing, and using oral reading assessment data. The recommendations are drawn from several articles in an ebook that describe various oral reading assessments used around the world. The assessments discussed range from household-based citizen-led assessments to school-based assessments and focus on evaluating early reading skills from ages 3 to grade 3. The goal is to provide guidance to practitioners on best practices for selecting, administering, and using oral reading assessments to improve literacy outcomes.

![45 ■ School-based Assessments: What and How to Assess Reading

support the testing approach and interpretation of

the results. Reliability is the overall consistency of

a measure—i.e. whether the measure generates

similar results under consistent conditions either

within a sample of like learners or across repeated

measures (American Educational Research

Association [AERA] et al., 2014; Glaser et al., 2001).

To borrow an example from the health sector, a

blood-pressure cuff is a valid way of measuring

blood pressure. It is not a valid way of assessing

how much an individual weighs. The blood-pressure

cuff is a reliable measure if it consistently reports

similar or same results for the same individual or

like individuals under similar conditions. If it were to

give wildly different results for an individual in two

applications several minutes apart, it would not be

considered a reliable measure.

The validity of the EGRA is tied to (1) the conceptual

underpinning of the tool (and its inclusion of

valid subtasks of early reading skills) and (2) the

usefulness of the results in reporting on student

performance in early reading. Overall validity is

sometimes characterised using four key aspects:

construct, content, concurrent, and predictive

validity (AERA et al., 2014). The second edition of

the EGRA Toolkit (2015) provides a substantial list

of references for each of the subtasks that support

the construct and content validity of the approach

in English (the French and Spanish versions of the

toolkit provide additional information for the validity

of the measures in those languages) (Sprenger-

Charolles, 2009; Jiménez, 2009). For more details

regarding these references, see Appendix I.

The EGRA Tooklit, Second Edition can be

accessed here

The EGRA has also been a part of several

concurrent-validity studies. Concurrent validity is

shown when an assessment correlates with another

assessment that has been previously validated.

This gives conidence that the assessments are

measuring the same construct and the results are

valid. In this stratagem, researchers simultaneously

(or concurrently) administer two assessments

(usually of the same or similar construct and content)

to the same student, then compare the results.

Studies attempting to validate the EGRA against

other validated assessments have been conducted

in Peru (Kudo and Bazan, 2009), Honduras and

Nicaragua (Bazan and Gove, 2010). The Kudo and

Bazan study (2009) in particular comprehensively

reviewed oral and written assessment studies of

concurrent validity. Studies seeking to validate other

studies against the EGRA include assessments

conducted in India (Vagh, 2012) and Kenya (ACER,

2015). For additional information, please see also

Vagh’s article on concurrent validity in this volume.

The correlations comparing the EGRA and other

assessments ranged from .41 to .98 and are

summarised in Table 2. The correlation coeficient

provides the strength of the linear relationship

between two variables, the closer to 1 the more

conidence one has that the assessments are

measuring the same construct. The high correlations

(.9–.97) are with other oral reading assessments from

India and Kenya. The Spanish assessments listed

were written tests, which accounts for medium-sized

correlations to the EGRA (.41–.47).

For details on how the studies were conducted,

please see the original reports (links available in the

reference list at the end of this article).

©

Dana

Schmidt/The

William

and

Flora

Hewlett

Foundation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingwhatworksinoralreading-220421155935/85/UNDERSTANDING_WHAT_WORKS_IN_ORAL_READING-pdf-46-320.jpg)

![50 ■ School-based Assessments: What and How to Assess Reading

REFERENCES

Aber, J.L. (under review). “Impacts of “Healing

Classrooms” on children’s reading and math skills

in DRC”. Journal of Research on Educational

Effectiveness.

ACER (2015). Report on the concurrent validity and

inter-rate reliability studies of Uwezo. Washington,

DC: Results for Development Institute (R4D).

Adams, M.J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and

learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Adelman, M., Baron, J.D., Blimpo, M., Evans,

D.K., Simbou, A. and Yarrow, N. (2015). Why

do students learn so little? Seeking answers

inside Haiti’s classrooms. World Bank Working

Paper 96500. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Retrieved from https://openknowledge.

worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/22064/

Why0Do0student0e0Haiti0s0classrooms.

pdf?sequence=1

American Educational Research Association

(AERA), American Psychological Association,

National Council on Measurement in Education,

Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and

Psychological Testing [US]. (2014). Standards for

educational and psychological testing. Washington,

DC: American Educational Research Association.

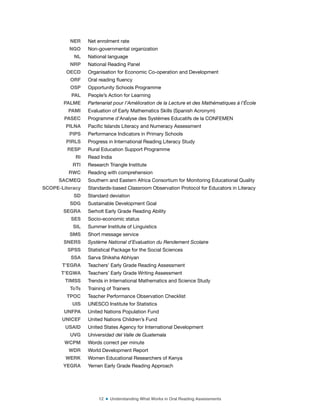

APPENDIX 1

Research supporting the EGRA approach and subtasks

Foundational skill

Measured by EGRA

subtask(s):

Supporting research—direct excerpt from the EGRA Toolkit, 2nd edition

(RTI International, 2015)

Phonological

awareness

Initial sound identiication; initial

sound discrimination

Optional: phoneme (or syllable)

segmentation

Phonological awareness has been shown across numerous studies in

multiple languages to be predictive of later reading achievement (Badian,

2001; Denton et al., 2000; Goikoetxea, 2005; McBride-Chang and Kail, 2002;

Muter et al., 2004; Wang, Park and Lee, 2006).

Alphabetic principle

and alphabet

knowledge

Letter identiication (either by

letter names or letter sounds);

nonword reading; familiar word

reading; dictation

Optional: syllable identiication

Research has shown alphabet knowledge to be a strong early predictor of

later reading achievement (Adams, 1990; Ehri and Wilce, 1985; Piper and

Korda, 2010; Wagner et al.,, 1994; Yesil-Dağli, 2011) for both native and

nonnative speakers of a language (Chiappe et al., 2002; McBride-Chang and

Ho, 2005; Manis et al., 2004; Marsick and Watkins, 2001). One of the main

differences between successful readers and struggling readers is the ability

of successful readers to use the letter-sound correspondence to decode

new words they encounter in text and to encode (spell) the words they write

(Juel, 1991).

Vocabulary and oral

language

None directly but indirectly

measured by listening

comprehension

Optional: vocabulary (untimed)

Reading experts have suggested that vocabulary knowledge of between

90 and 95% of the words in a text is required for comprehension (Nagy and

Scott, 2000). It is not surprising then, that in longitudinal studies, vocabulary

has repeatedly been shown to inluence and be predictive of later reading

comprehension (Muter et al., 2004; Roth et al., 2002; Share and Leiken, 2004).

Fluency Oral reading luency with

comprehension

Timed and scored for speed

and accuracy: letter name

identiication, letter sound

identiication, nonword reading,

and familiar word reading

Numerous studies have found that reading comprehension has a relationship

to luency, especially in the early stages (Fuchs et al., 2001). For example,

tests of oral reading luency, as measured by timed assessments of correct

words per minute, have been shown to have a strong correlation (0.91)

with the reading comprehension subtest of the Stanford Achievement Test

(Fuchs et al., 2001). The importance of luency as a predictive measure does,

however, decline in the later stages. As students become more proicient

and automatic readers, vocabulary becomes a more important predictor of

later academic success (Yovanoff et al., 2005).

Comprehension Reading comprehension

Optional: maze; cloze

Research has not yet produced a proven means to consistently and

thoroughly test the higher-level and more nuanced comprehension skills in

a standardised way that could be accepted as valid and reliable. However,

options are under consideration and it is hoped that the measurement of

comprehension will continue to improve as this skill is one of the most

important measures of reading success.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingwhatworksinoralreading-220421155935/85/UNDERSTANDING_WHAT_WORKS_IN_ORAL_READING-pdf-51-320.jpg)

![56 ■ School-based Assessments: What and How to Assess Reading

Rosenkranz, E., Jonason, C. and Kajangwa, D.

(2014). Literacy Boost Burundi endline report,

August 2014. Washington, DC: Save the Children.

http://resourcecentre.savethechildren.se/

library/literacy-boost-burundi-endline-report-

august-2014

Roth, F.P., Speece, D.L. and Cooper, D.H. (2002). “A

longitudinal analysis of the connection between oral

language and early reading”. Journal of Educational

Research, Vol. 95, pp. 259-272.

RTI International. (2009). Early grade reading

assessment toolkit. Research Triangle Park,

NC: RTI International.

RTI International. (2013). The Primary Math and

Reading (PRIMR) Initiative: Annual report, 1

October 2012–31 September 2013. Prepared under

the USAID Education Data for Decision Making

(EdData II) Project. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI.

http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00K262.pdf

RTI International. (2014). Girls’ Improved Learning

Outcomes: Final report. Research Triangle Park,

NC: RTI International. http://pdf.usaid.gov/

pdf_docs/pa00jtbc.pdf

RTI International. (2015). Early Grade Reading

Assessment toolkit, Second Edition, prepared

for USAID under the Education Data for Decision

Making (EdData II) project, Research Triangle

Park, NC: RTI. http://static1.squarespace.

com/static/55c4e56fe4b0852b09fa2f29/t/56

e0633545bf213c2b5269e5/1457546040584/

EGRA+Toolkit+Second+Edition_March_8_2016+.

pdf

RTI International (2015). Tout Timoun Ap Li - ToTAL

(All Children Reading) final report, REVISED, 2

August 2012–5 December 2014 [Haiti]. Prepared

under the Education Data for Decision Making

(EdData II) project. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_

docs/PA00K911.pdf

RTI International and International Rescue

Committee (IRC). (2011). Guidance notes for

planning and implementing early grade reading

assessments. Washington, DC: RTI and IRC.

https://www.eddataglobal.org/reading/index.

cfm?fuseaction=pubDetail&id=318

Save the Children (2013). Reading is the future: Lekti

se lavni: baseline-endline assessments report [Haiti].

Washington, DC: Save the Children. http://

resourcecentre.savethechildren.se/library/

reading-future-lekti-se-lavni-baseline-endline-

assessments-report

Save the Children (2013). Save the Children

International Basic Education Program: TiANA

project endline report, 2013 [Malawi]. Washington,

DC: Save the Children. http://resourcecentre.

savethechildren.se/library/save-children-

international-basic-education-program-tiana-

project-endline-report-2013

Save the Children (2014). TiANA final evaluation

report for ST Anthony and Namadidi education zone,

Zormba rural, Malawi, September 2014. Washington,

DC: Save the Children. http://resourcecentre.

savethechildren.se/library/tiana-final-evaluation-

report-st-anthony-and-namadidi-education-zones-

zormba-rural-malawi

Seymour, P.H., Aro, M. and Erskine, J.M. (2003).

“Foundation literacy acquisition in European

orthographies”. British Journal of psychology, Vol.

94, No. 2, pp. 143-174.

Share, D.L. and Leikin, M. (2004). “Language

impairment at school entry and later reading

disability: Connections at lexical versus supralexical

levels of reading”. Scientific Studies of Reading, Vol.

8, pp. 87-110.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingwhatworksinoralreading-220421155935/85/UNDERSTANDING_WHAT_WORKS_IN_ORAL_READING-pdf-57-320.jpg)

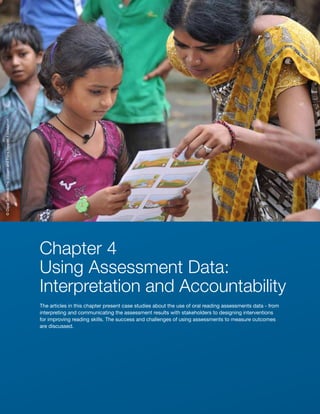

![203 ■ Is Simple, Quick and Cost-Effective Also Valid? Evaluating the ASER Hindi Reading Assessment in India

provide supporting evidence for the validity of the

ASER reading assessments, this paper presents the

content validity of the ASER reading assessment

and examines children’s concurrent performance on

the ASER Hindi reading assessment compared to

other assessments of reading. Data are drawn from

a large-scale randomised evaluation of Pratham’s1

reading and arithmetic intervention programme by

the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

for which the ASER reading assessment was used

along with a battery of other reading and arithmetic

assessments. Speciic and detailed comparisons are

made between the ASER reading assessment and

another widely prevalent model of assessing early

reading ability, the Early Grade Reading Assessment

(EGRA), which had been adapted for use in Hindi

(also see www.eddataglobal.org) (Dubeck

and Gove, 2015; Gove and Wetterberg, 2011). In

addition, the ASER is compared to the Read India

Literacy assessment, a pen-and-paper assessment

of children’s basic and advanced Hindi literacy skills.

2. VALIDITY IN THE CONTEXT OF THE

ASER READING ASSESSMENT

Validity indicates whether a test assesses what

it purports to assess and is an evaluation of a

test’s inference and not of the test per se. A test

can be put to different uses, such as examining

average school performance or making diagnostic

decisions for individual students. Each of these

uses or inferences “has its own degree of validity,

[and] one can never reach the simple conclusion

that a particular test ‘is valid’” (Cronbach, 1971,

p.447). Several forms of evidence are collected

to evaluate the validity of the inferences that are

based on the test results. As such, validity is an

accumulating body of evidence (AERA et al., 1985).

One form of evidence is content validity, which

indicates the extent to which the content is a

representative sample of the domain of interest and

whether it assesses the desired or targeted skills

1 Pratham is an Indian non-government organization working on

large scale to ensure that every child is in school and learning

well. Pratham runs a variety of programmes in 21 states

around India and works directly with communities and schools

as well as with governments to work towards these goals. See

www.pratham.org for more details.

and abilities. Another form of evidence, a common

empirical investigation termed “concurrent validity”

involves comparing performance on the assessment

of interest with performance on a comparable

assessment that serves as a criterion measure.

The criterion assessment is typically another

assessment of known psychometric properties

that assesses similar abilities or constructs. In

this study, as noted above, we are comparing the

performance on the ASER reading assessment with

children’s performance on the EGRA and the Read

India Literacy assessment. Strong and positive

associations between the three assessments will

contribute to evidence that serves as one part of

building a full validity argument for the ASER reading

assessment.

2.1 Content of the ASER reading assessment

The ASER reading assessment is designed to

capture children’s early reading skills in 20 Indian

languages. For the Indian orthographies, the basic

orthographic unit is the ‘akshara’, which represents

sounds at the syllable level with its constituent

parts encoding phonemic information. The akshara

can vary from simple to complex depending on

the extent of the phonemic information encoded.

The primary forms of vowels and consonants

with an inherent vowel that is unmarked comprise

the set of simple akshara and contrast with the

complex akshara that comprise ligatures that are

consonants with vowel markers or consonant

clusters with a marked or unmarked vowel. Given

that the ASER reading assessment is designed to

assess early and basic reading skills, its subtasks

assess children’s knowledge of the simple akshara,

ability to accurately decode simple words and

ability to luently read a Grade 1 and Grade 2 level

passage. The selection of the subtasks is based on

the premise that the acquisition of symbol-sound

mapping and the ability to decode symbol strings

are among the early set of skills that contribute to

reading in the Indian alphasyllabaries akin to the

alphabetic orthographies (Nag, 2007; Nag and

Snowling, 2011). Although the pace of acquisition

of the akshara tends to be extended given the

extensive set of orthographic units that children](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingwhatworksinoralreading-220421155935/85/UNDERSTANDING_WHAT_WORKS_IN_ORAL_READING-pdf-204-320.jpg)

![232 ■ Use of Literacy Assessment Results to Improve Reading Comprehension in Nicaragua’s National Reading Campaign

The IPADE also created a baseline with two

indicators: luency and reading comprehension. The

EGRA’s short version was administered in 2014 in

20 schools in the municipality of Siuna located in

the RACN. The study covered 323 students—all the

children present in their Grade 1 classrooms when

the test was administered.

The baseline indicated that 42% of students

achieved the reading luency goal of 28 words

correct per minute (WCPM) in September—three

months before the end of the school year. The

assessment showed that 33% responded correctly

to the questions related to the passage read.

This gap of nearly 9% between the percentage of

students able to achieve luency and the percentage

of students who comprehend the passage has been

a constant during the campaign.

The assessments conducted during the ive years

of the campaign have yielded consistent results

showing that the number of students reaching

the luency goal always exceeds the number of

students who understood what they read. When

the campaign committee analysed this gap (9%

or more per year), it drew the conclusion that

comprehension limitations are probably linked to

a knowledge gap (Snow, 2015) associated with

several factors, including low levels of education of

children´s mothers, scarce enrolment in preschool

and malnutrition. Therefore, these children enter

Grade 1 with weaknesses in their oral vocabulary,

precursory literacy skills and have dificulties

making meaning from stories not related to their

context. Lending credence to this assumption,

the reading skills diagnosis performed in the

Caribbean in 2010 found that the percentage of

preschool attendance among Miskito children was

4% (Castro et al., 2010). Therefore, it is possible

that the literacy efforts that began six years ago

are helping to improve children’s decoding skills.

Despite improvements, greater efforts should

be made to close this knowledge gap, expand

children’s vocabulary and train them in the use of

strategies to improve comprehension. The results

found in a study performed by the Regional Child

Development Indicator Project (Verdisco et al., 2014)

in four Latin American countries also underscores

the need for greater efforts to improve learning. This

study measured, among other things, language and

communication development in children aged 2 to 4

years using the PEABODY test (IPTV) and the Engle

Scale. Nicaragua scored below the regional average

and was the country with the lowest average

score in the area of language and communication

development.

4.2 Quality of education should be everyone’s

concern: community and family participation

The research by the external consultant for Save

the Children demonstrated that the CAPRI´s work

over several years in the Vamos a Leer campaign

has promoted a qualitative leap in the participation

of families (Rivera, 2014). The campaign has helped

teachers involve parents in reading and telling

stories to their children. This initiative by the CAPRI

and other NGOs was sparked during the 2011

competition when parents borrowed books from

their friends and families to prepare their children

for the contest. The involvement of families in the

learning of children has driven parents to overcome

the tendency of only participating in logistical tasks

at the school, such as preparing meals and cleaning

the educational centres. A mother interviewed by

Rivera stated, “my role as a mother is to help them

study, help them with homework at home [...] the

teacher told us that families can support [children]

by reading, accompanying them when they’re doing

their homework tasks”.

World Vision has also been promoting parent training

to support inclusion and diminish drop out rates in

schools that enrol children living in extreme poverty.

In 2014, 288 parents and 888 children were trained.

Another interesting initiative to promote community

and family participation has been the creation of

Caminos Letrados (letter roads). Considering that

there are no advertising signs in rural areas and

that children’s exposure to printed letters is almost

nonexistent, World Vision designed a strategy to

encourage parents to create cardboard signs with

mottos and educational sentences for children to

read when walking to or from school.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingwhatworksinoralreading-220421155935/85/UNDERSTANDING_WHAT_WORKS_IN_ORAL_READING-pdf-233-320.jpg)

![234 ■ Use of Literacy Assessment Results to Improve Reading Comprehension in Nicaragua’s National Reading Campaign

m Reading dificulties

m Phonological awareness and alphabetic code

m Fluency, vocabulary and reading comprehension

m Teaching strategies through play-like activities to

expand vocabulary and improve comprehension

m Strategies to improve reading habits and develop

a love for reading

m Reading process evaluation

m Management and use of the EGRA’s data

m How to develop education plans with appropriate

indicators using the EGRA’s data to improve

the teaching and learning of literacy skills in

kindergarten and the irst three grades of primary

school.

In 2015, Save the Children is tendering the repetition

of the training course—this time to be offered to

primary teachers in some of the municipalities

attended by its counterparts.

Three of CAPRI’s oficers took the course in

Managua along with six MINED advisers working in

the districts of Managua where the CAPRI provides

its services. The IPADE participated with four

representatives (two of its oficials and two MINED

advisors for Siuna).

This course and other trainings received by CAPRI

oficials have played a key role in expanding training

opportunities of “educational counselors and

MINED teachers” (Rivera, 2014). One of CAPRI’s

central activities is to support the team of MINED

educational advisers in Managua, providing them

with the opportunities to train in various literacy

teaching topics. Following each training session,

CAPRI and MINED departmental advisers and

technicians reproduce the workshop among district

advisors in Managua who in turn reproduce these

training efforts with principals and teachers.

Rivera quotes (2014) a pedagogical adviser stating,

“teachers are more encouraged to teach, thanks

to the teaching strategies and methodologies

provided to develop the content of school literacy

curricula”. Others teachers quoted stated that “the

trainings sponsored by CAPRI have provided us

with tools to strengthen the teaching of literacy

... as well as to seek students’ involvement in

learning” (Rivera, 2014).

The mother of a child in a class of 52 students who

won the 2014 contest, placed a high value on the role

played by the teacher stating “the teacher played a

key role in children learning how to read. She was very

organized, identiied the children who were having

dificulties, sorted them by groups and explained what

they did not understand [...] they identiied letters,

divided syllables, did spelling, participated in the

board, and motivated them to read.”

The training also contributed to a positive

atmosphere that encouraged reading in the

classroom. For example, in the Grade 1 classes

of the school República de El Salvador (multiple

winner in the reading campaign’s contest) in

Managua, the three classrooms visited by Rivera

(2014) with over 50 students each were in classes

called aulas letradas (literate classrooms) and all

three classes featured letters, numbers, images,

colors, clippings from magazines, newspapers and

posters on their walls. According to the teachers

interviewed, this setting helped the students

identify vowels and consonants as well as form

syllables and words.

The CAPRI has also trained librarians to help foster

a fun literacy learning culture, encourage the use

of libraries and maximise the number of children’s

books available. The goal of these trainings was to

encourage children to borrow books to take home

as a means of recreation and avoid the practice of

locking books away to prevent them from being

damaged (Rivera, 2014).

World Vision reported in 2014 that it has been

training teachers in the use of various methodologies

to improve literacy learning. In 2014, World Vision

provided teachers with several courses on the

development of preliterate preschool skills. One of the

courses called “playing, talking and drawing to learn

how read” was attended by 28 preschool teachers.

The focus of another course, “let’s venture into the

wonder of reading”, was to encourage children’s

reading habits and was taught to 101 teachers of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingwhatworksinoralreading-220421155935/85/UNDERSTANDING_WHAT_WORKS_IN_ORAL_READING-pdf-235-320.jpg)