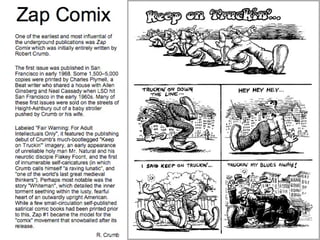

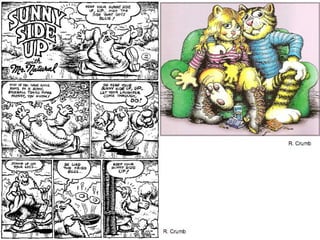

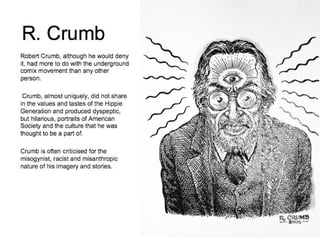

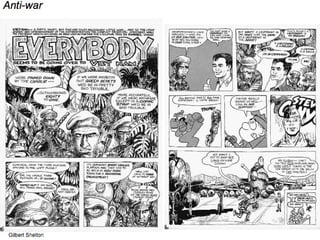

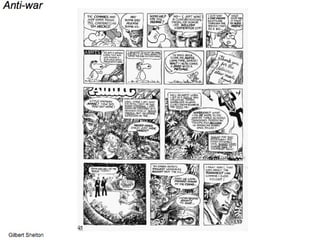

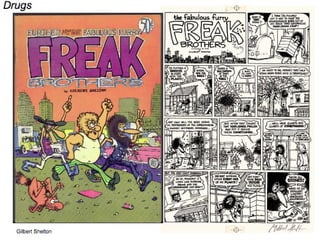

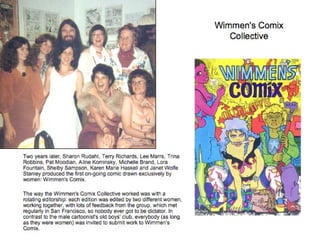

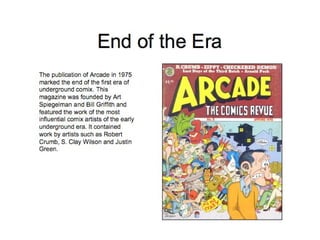

The document summarizes the history of underground comix that emerged in the late 1960s in the United States. The comix aligned with counterculture movements and tackled taboo topics using innovative styles. They were self-published and distributed through head shops, bypassing censorship. Notable early titles included Robert Crumb's Zap Comix. The comix movement influenced the development of alternative comics and challenged conventions.