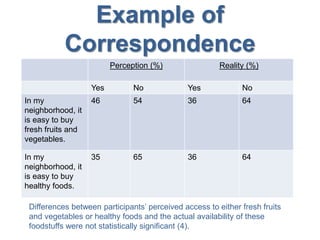

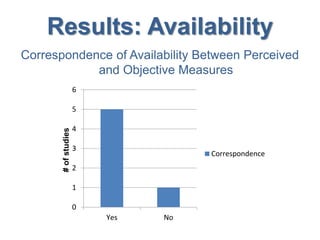

This document summarizes research on the correspondence between perceived and objective measures of neighborhood food environments. Six studies examined the correspondence between perceptions of access to healthy foods and actual availability as measured by audits and GIS mapping. Results found some correspondence, such as residents with lowest supermarket densities rating availability lower. However, perceptions did not always match reality, like on cost. Recommendations include using both perceived and objective measures in more diverse locations while standardizing methods. Future research should consider all food sources and cultural factors to better understand how perceptions influence health behaviors.