The document provides details about an upcoming 500-750 word case study analysis assignment focused on cultural competence in education. Students must analyze specific cases relating to American Indian, Latino, African American, or Asian American students, addressing how cultural backgrounds influence interactions and educational challenges in the classroom. It emphasizes the use of scholarly sources, adherence to APA style, and the importance of understanding cultural differences to support students effectively.

![Topic 5 Assignment Reminders

Class,

I just wanted to remind you about our weekly assignment. This

week you will be submitting one assignments. Please make sure

that you completely review the assignment page.

Case Study Analysis- This assignment is 500-750-word rough

draft. We will use the provided template for this (attached to

this post). In the assignment you will be analyzing a case study

from the resource “For Cultural Competence: Knowledge, Skills

and Dispositions Needed to Embrace Diversity” and are listed in

the table of contents.

1. Make sure to review “For Cultural Competence: Knowledge,

Skills and Dispositions Needed to Embrace Diversity” in the

course materials. Without this resource you will not be able to

complete the assignment.

2. Support your work with citations 2-3 scholarly journal

articles preferably from the last 3 years.

3. Make sure to use the template (attached below) and follow all

directions on the template.

4. Follow APA Style (https://www.gcumedia.com/lms-

resources/student-success-center/v3.1/#/tools/writing-

center [click Style Guides and Templates on this page and then

you will see the APA Style Guide and Template]).

5. The assignment must address all prompts on the assignment

page.

6. Submit your work to your work to Lopes Write and then

complete your final submission in the dropbox.

If you have any questions please let me know, and I hope that

everyone has a great week.

Instruction for the Assignment

Select Case Study 3.5, 3.7, 3.8, or 3.9 in “For Cultural

Competence: Knowledge, Skills and Dispositions needed to

Embrace Diversity.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/topic5assignmentremindersclassijustwantedtoremindyou-221012014910-2746ce3d/75/Topic-5-Assignment-RemindersClass-I-just-wanted-to-remind-you-docx-1-2048.jpg)

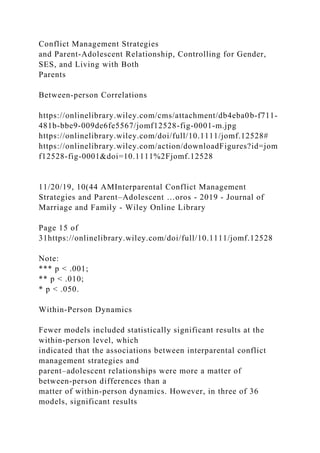

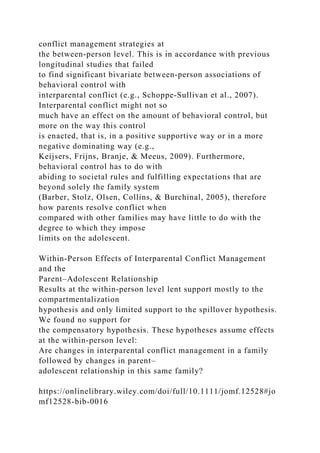

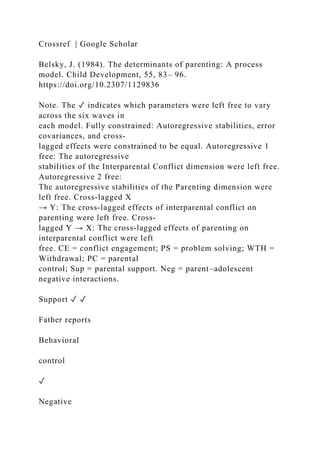

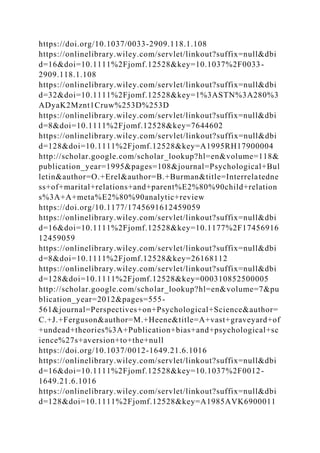

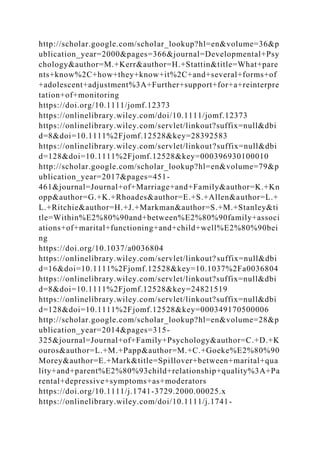

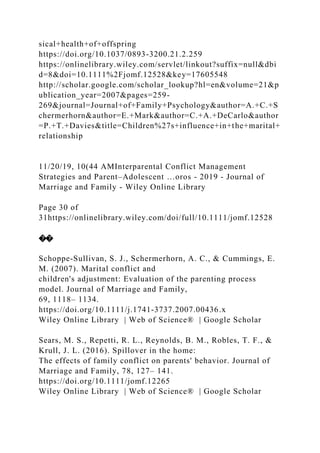

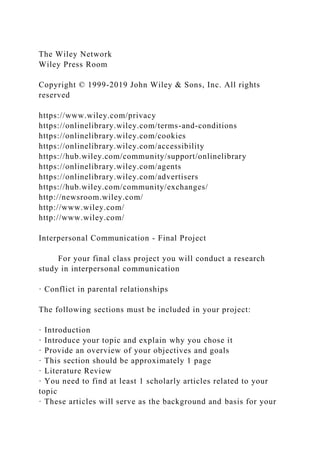

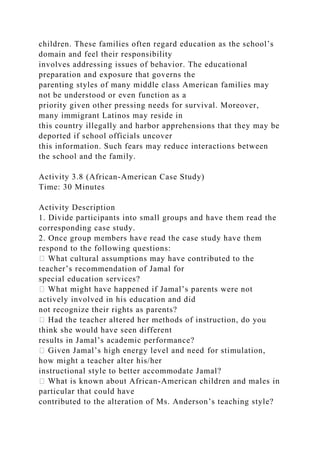

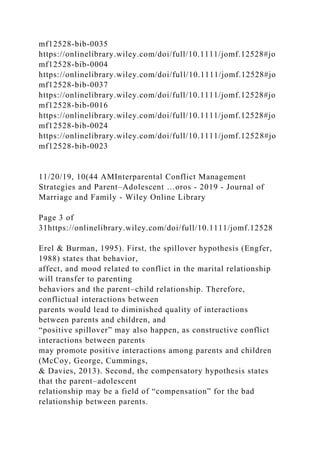

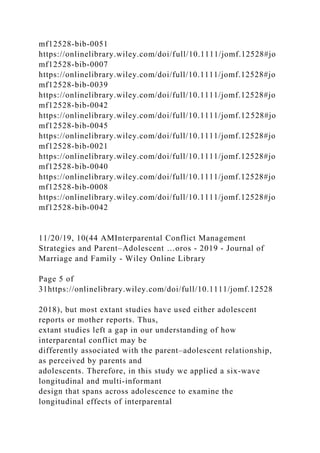

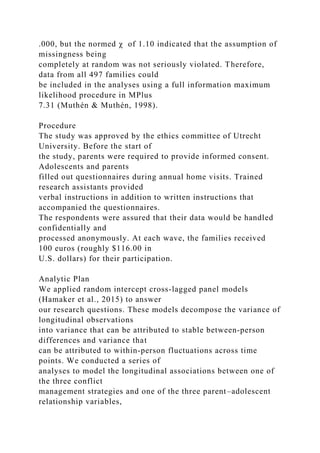

![MA neg. int 1.52 0.53 1.55 0.54 1.53 0.50 1.55 0.56 1.50 0.54

1.48 0.54 0.62

FA neg. int 1.51 0.50 1.52 0.53 1.51 0.52 1.53 0.51 1.51 0.53

1.47 0.50 0.62

AM control 3.73 1.00 3.59 1.01 3.39 1.03 3.27 1.09 2.90 1.14

2.58 1.15 0.34

AF control 3.37 1.06 3.17 1.07 3.02 1.04 2.89 1.05 2.64 1.05

2.28 1.00 0.38

Conflict engagement

Mother reports

Behavioral control 113.90 83 .99 0.03 [0.01–0.04] .04 .99

Negative interactions 103.20 87 1.00 0.02 [0.00–0.03] .03 .99

Support 167.00 79 .97 0.05 [0.04–0.06] .07 .99

Father reports

Behavioral control 241.60 83 .94 0.07 [0.06–0.08] .13 .99

Negative interactions 99.80 87 1.00 0.02 [0.00–0.03] .03 .99

Support 150.80 83 .98 0.04 [0.03–0.05] .06 .99

Scales χ2 df CFI RMSEA [90%CI] SRMR Power

11/20/19, 10(44 AMInterparental Conflict Management](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/topic5assignmentremindersclassijustwantedtoremindyou-221012014910-2746ce3d/85/Topic-5-Assignment-RemindersClass-I-just-wanted-to-remind-you-docx-44-320.jpg)

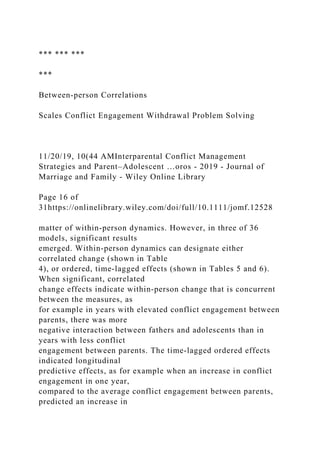

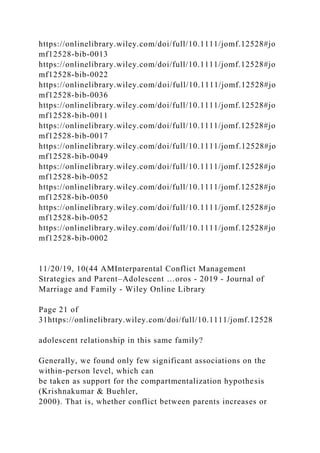

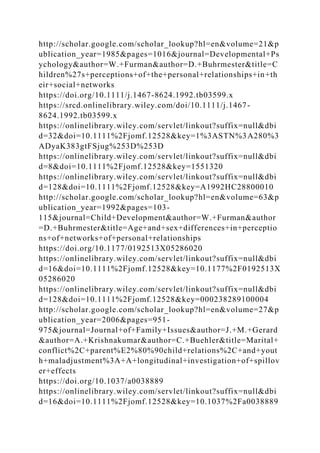

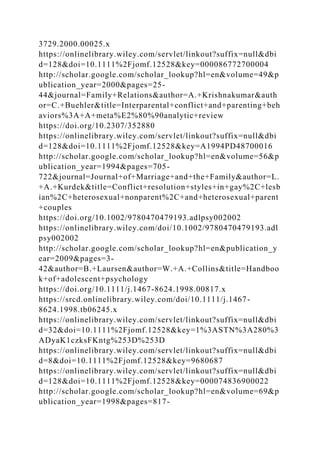

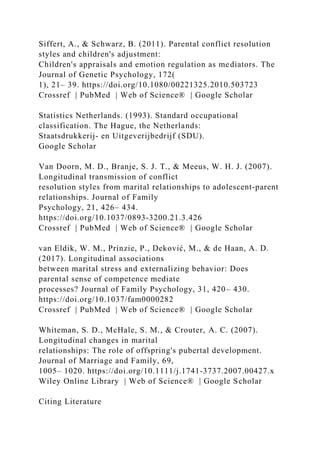

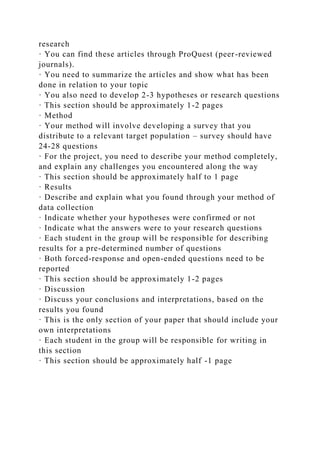

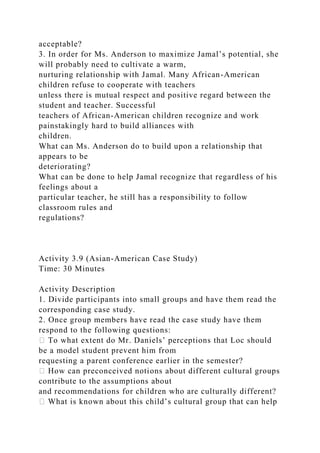

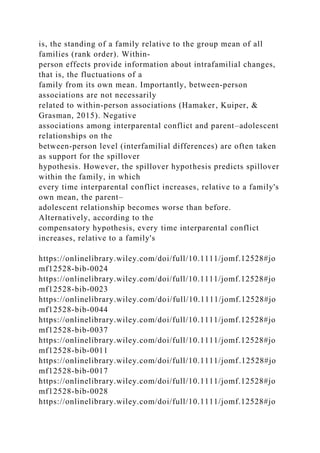

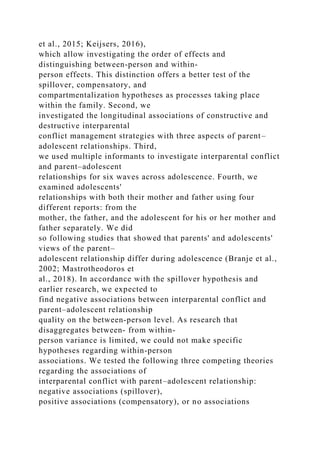

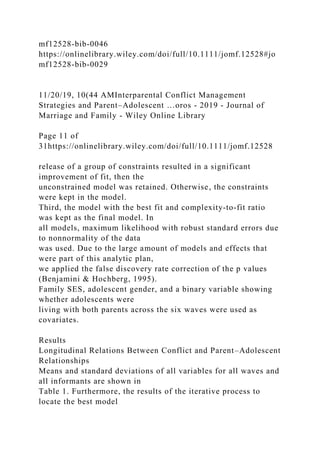

![graphically illustrates this model.

Problem solving

Mother reports

Behavioral control 95.10 79 .99 0.02 [0.00–0.04] .07 .99

Negative interactions 89.40 83 1.00 0.01 [0.00–0.03] .07 .99

Support 171.80 79 .97 0.05 [0.04–0.06] .10 .99

Father reports

Behavioral control 210.90 79 .94 0.06 [0.05–0.07] .12 .99

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jomf.12528#jo

mf12528-bib-0029

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/cms/attachment/db4eba0b-f711-

481b-bbe9-009de6fe5567/jomf12528-fig-0001-m.jpg

11/20/19, 10(44 AMInterparental Conflict Management

Strategies and Parent–Adolescent …oros - 2019 - Journal of

Marriage and Family - Wiley Online Library

Page 14 of

31https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jomf.12528

Figure 1

Open in figure viewer PowerPoint

A Random Intercept Cross‐Lagged Panel Model as applied in

this study.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/topic5assignmentremindersclassijustwantedtoremindyou-221012014910-2746ce3d/85/Topic-5-Assignment-RemindersClass-I-just-wanted-to-remind-you-docx-46-320.jpg)