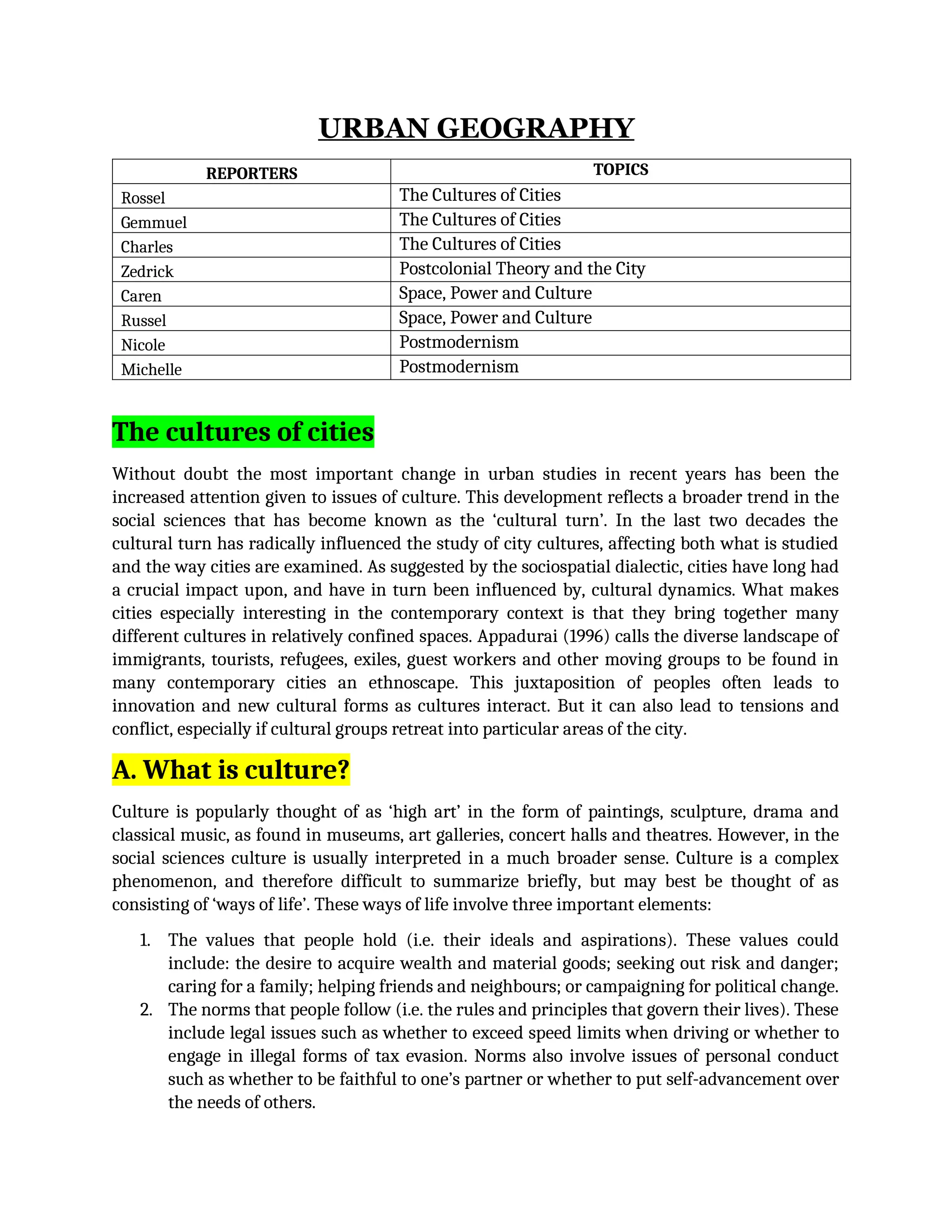

The document discusses the cultural turn in urban studies, emphasizing how cultural dynamics shape and are shaped by urban environments. It highlights the significance of culture as a complex phenomenon, encompassing values, norms, and material objects, and explores themes of identity, diversity, power relations, and postcolonial theory in the context of cities. The analysis includes insights on how urban landscapes reflect societal values and cultural tensions, illustrating the interplay between different cultural groups and their impact on social geography.