Understanding Development Through Student Perspectives

- 1. iii

- 3. 3

- 4. An undercurrent, by definition, is the unseen movement of water beneath the surface; its tug and motion are only perceptible upon submersion. It is an apt metaphor both for international development studies and its undergraduates. The intriguing tensions and debates within the field of IDS flow beneath a popularized veneer of humanitarian charity. And we, its undergraduates, study at the margins of the arena of the academy – much of our vitality and dynamism hidden from view. Undercurrent is a publication that immerses its readers in the ebbs and flows of development studies through the perspective of Canadian undergraduates. Indelibly marked by the legacy of colonialism and the onward march of global integration, international development studies is a field illuminated by our confrontation with human difference and inequality. The just pursuit of unity in diversity promises to be a reiterating challenge for the next century, and water is a fitting icon for such a pursuit: an elemental reminder of our fundamental oneness that, through its definition of our planetary geography, also preserves our distance. With aspirations of distinction, we are proud to offer Undercurrent. *** Un undercurrent (courant de fond), par définition, est le mouvement invisible de l’eau sous la surface. Son va-et-vient est seulement apparent par submersion. Ceci est une métaphore à propos des études de développement international et des étudiants au baccalauréat. Les tensions et les débats fascinants au sein du domaine du développement international circulent sous l’aspect superficiel de la charité. De manière comparable, nous qui étudions aux marges du champ académique voyons que notre vitalité et notre dynamisme sont souvent masqués aux regards d’autrui. Undercurrent est une publication qui immerge ses lecteurs dans le flux et le reflux des études de développement international à travers la perspective d’étudiants canadiens. Indélébilement marquées par l’héritage du colonialisme et de l’intégration mondiale actuelle, les études de développement international sont un champ éclairé par notre confrontation avec la différence humaine et l’inégalité. La poursuite judicieuse d’une unité au sein de la diversité promet d’être un défi récurrent pour le siècle à venir. L’eau est une image appropriée pour une telle quête : elle est un rappel élémentaire de notre unité fondamentale, qui, parce qu’elle définit notre géographie planétaire, préserve aussi notre distance. Avec des ambitions de distinction, nous sommes fiers de présenter Undercurrent. iii

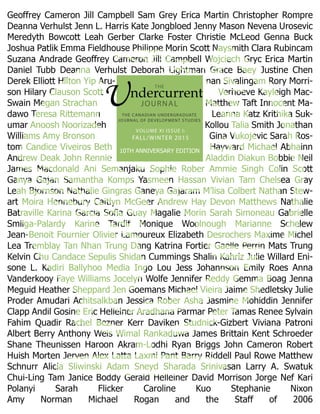

- 5. iv Editor-in-Chief Christie McLeod, University of Winnipeg/Menno Simons College Managing Editor M’Lisa Colbert, Concordia University Outreach Coordinator Nathan Stewart, University of Guelph Associate Editors Vivian Tam, McMaster University Moira Hennebury, University of Waterloo Caitlyn McGeer, Memorial University Andrew Hay, Carleton University Devon Matthews, Dalhousie University Webmaster/Design Editors Shidan Cummings, University of Ottawa Translators Kelvin Chu, University of Toronto Advisory Committee Clarke Foster, Dalhousie University Emma Fieldhouse, University of Winnipeg/Menno Simons College Amy Bronson, University of Guelph Faye Williams, University of Ottawa Faculty Editorial Advisors Haroon Akram-Lodhi, Trent University Ryan Briggs, American University John Cameron, Dalhousie University Robert Huish, Dalhousie University Morten Jerven, Simon Fraser University Alex Latta, Wilfrid Laurier University Laxmi Pant, Special Graduate Lecturer - University of Guelph, Barry Riddell, Queen's University Paul Rowe, Trinity Western University Matthew Schnurr, Dalhousie University Alicia Sliwinski, Wilfrid Laurier University Adam Sneyd, University of Guelph Sharada Srinivasan, York University Larry A. Swatuk, University of Waterloo Chui-Ling Tam, University of Calgary Cover Design Christie McLeod, University of Winnipeg/Menno Simons College Founding Editors Geoffrey Cameron Jill Campbell Sam Grey Erica Martin Christoper Rompré Deanna Verhulst About Undercurrent is the only student-run national undergraduate journal publishing scholarly essays and articles that explore the subject of international development. While individual authors may present distinct, critical viewpoints, Undercurrent does not harbour any particular ideological commitments. Instead, the journal aims to evince the broad range of applications for development theory and methodology and to promote interdisciplinary discourse by publishing an array of articulate, well-researched pieces. Undercurrent endeavours to raise the profile of undergraduate IDS; to establish a venue for young scholars to undergo constructive review and have work published; to provide the best examples of work currently being done in undergraduate IDS programmes in Canada; and to stimulate creative scholarship, dialogue and debate about the theory and practice of development. undercurrentjournal.ca Ten years ago, development studies students gathered in the central Canadian city of Winnipeg for the Canadian Association for the Study of International Development (CASID) Annual Meeting. It was at this fateful gathering that the students decided to create their own annual meeting -‐-‐ InSight -‐-‐ which then gave birth to the Undercurrent. The Undercurrent is now in its 10th year of publication. Since its humble beginnings in 2004, with the dedication and tireless work of 157 staff members, the Undercurrent has published 158 papers in 23 issues. These papers have offered a critical perspective of development studies subjects, which have positioned the Undercurrent as an important body of literature within the Oield of development. InSight has had seven annual meetings, and the Undercurrent team is actively preparing for the 2015 conference occurring in Ottawa. Additionally, the Undercurrent has also executed a successful mentoring program, is initiating a National International Development Student Association and has published 46 blog posts on its website (including the recent 10 Posts in 10 Days feature leading up to the release of this issue). The Undercurrent provides a space for students to voice their opinions and critically engage with research on a wide array of topics. Our unique editorial process serves as a learning instrument for the dedicated contributors and peer editors. This fall’s editorial cycle has produced a remarkable compilation of works from development studies students Canada-‐wide: Patrick Balazo examines the international community’s responsibility in defending the human rights of stateless persons; Hannah Hong presents a compelling argument for the problematic injustices concealed by ‘single story’ narratives of Africa; Ayesha Barmania looks at the differences between immigrant communities in small cities and urban centres in Canada; Colton Brydges discusses the role of external actors in African mineral economies; Melissa Jackson utilizes a postcolonial feminism lens to advance the role of women as integral agents of social change in the Arab world; and Matthew Farrell presents, in French, a neo-‐Gramscian case study to argue that civil society cannot solve the failure of globalization. The Undercurrent would like to thank all of the past and present staff and authors who are named on our nifty commemorative front and back covers, respectively. We recognize that for every name listed, there is an accompanying cluster of people who supported the hard work and ambition of these individuals. We are extremely grateful to the founding editors, whose bright ideas and perseverance brought the Undercurrent to life in 2004. We look forward to seeing where the next generation of development studies students take the Undercurrent in future years! On behalf of the Undercurrent staff, it is with great pleasure that I present you with the 10th Anniversary Issue of the Undercurrent: The Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Development Studies. Happy birthday to us -‐-‐ and happy reading to you! Sincerely, Christie McLeod Editor-‐in-‐Chief Undercurrent: The Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Development Studies Letter from the Editor

- 6. CONTENTS iii Preface iv Letter from the Editor 6 Truth & Rights: Statelessness, Human Rights, and the Rohingya By: Patrick Balazo 16 “Africa Rising”: A Hopeless Falsity or a Hopeful Reality By: Hannah Hong 23 Practically a Community: Dynamics of a Small City’s Immigrant Community By: Ayesha Barmania 30 Feeling the Pressure: The Role of External Actors in the Development of the Mining Sectors of Tanzania and Zambia By: Colton Brydges 38 A Season of Change: Egyptian Women’s Organizing in the Arab Spring By: Melissa Jackson 47 L’Union de l’Économie et de l’État: Un Analyse Néo-Gramscien de la Défaillance de la ! Mondialisation et ses Effets au Bangladesh By: Matthew Farrell 56 Biographical Sketches 58 Contacting the Journal

- 7. Truth & Rights: Statelessness, Human Rights, and the Rohingya By: Patrick Balazo Abstract - The Rohingya people are a stateless Muslim community that live within the borders of Myanmar. This paper presents the gross human rights violations they have experienced and unveils a paradox in international law concerning state sovereignty that prevents them from claiming their right to a nationality and simultaneously prevents the international community from coming to their aid. This paper examines the plight of the Rohingya people using a specific conceptual framework of statelessness and it concludes that the inaction of the international community has caused their circumstances to worsen. Résumé - Les Rohinya sont une communauté musulmane apatride qui vit à l’intérieur de Myanmar. Ce papier présente les violations des droits humains qu’ils ont subies et dévoile un paradoxe dans le droit international concernant la souveraineté d’un état, ce qui les empêche de revendiquer leur droit à une nationalité et bloque simultanément l’aide de la communauté internationale. Ce papier examine la situation difficile des Rohinya en utilisant un cadre conceptuel spécifique de l’apatridie. Il conclut que l’inaction de la communauté internationale a aggravé leur situation. INTRODUCTION State sovereignty is paramount where it concerns international relations. Yet, for the Rohingya people of Myanmar, state sovereignty is a double sided iron veil that keeps them in legal shadows as a stateless people and simultaneously precludes the international community from bearing any responsibility in defending their human rights. The thesis of this paper uses a conceptual framework of statelessness to investigate the plight of the Rohingya people of Myanmar, drawing attention to the gross human rights violations that this group suffers as a result of their statelessness. The importance of such work lies in the fact that the dearth of academic literature regarding the plight of the Rohingya and the human rights violations they have been subjected to is written with a focus on the concept of statelessness in general, where the Rohingya serve merely as an example to this end. This thesis provides a more specific and in depth analysis of the case of the Rohingya people. The paper highlights how the suffering of the Rohingya has continued to escalate despite multiple international instruments designed to offer stateless peoples redress, and though evidence of the desperate conditions under which the Rohingya live is widely available, the international community is both unwilling and unable to act; an inaction that some commentators have characterized a “slow genocide” (The Sentinel Project, 2013, p. 36). WHO ARE THE ROHINGYA The Rohingya people are a stateless Muslim ethnic minority living in what is now Myanmar’s northwestern Rakhine state (historically referred to as Arakan). Today, they comprise over thirty percent of the state’s population, while their total numbers in Myanmar exceed two million (Parnini, Othman & Ghazali, 2013). Holliday (2010) argues that the Rohingya may be “the most distinctive of Myanmar’s many ethnic groups” (p. 121), with their religion, social customs and physical features setting them apart from the majority of Burmese society. It is during the fifteenth century that the people now known as the Rohingya began to figure prominently in the region’s history. In 1404, then king of Arakan Narmeikhla waged an attack on neighbouring Burma, and upon his defeat sought refuge in the court of the Muslim Bengali ruler Jalaluddin Shah (Oberoi, 2006, p. 172; Karim, 2000, p. 15). In 1430, Jalaluddin Shah’s forces reinstated Narmeikhla as the ruler of Arakan, cementing the influence Islam was to have on Arakan’s future (Oberoi, 2006, p. 172; Jilani, 2001, p. 15; Karim, 2000, p. 15). 6 Undercurrent Journal Volume XI, Issue I: Fall/Winter 2015

- 8. Arakan remained an independent Islamic kingdom until 1784 when Bodawpaya, the king of neighbouring Burma, conquered Arakan and incorporated it into his kingdom (Ahmed, 2010; Bahar, 2010; Oberoi, 2006). This event also marked the first mass exodus of Muslims from Arakan to Bengal (Bangladesh), with some 200,000 Muslims taking flight (Bahar, 2010; Oberoi, 2006). By 1798, two-thirds of Arakan’s population had deserted their native land (Jilani, 2001, p. 70). While this is indeed a dark chapter in the history of Arakan, an event that occurred the following year is of invaluable importance: the publication of Francis Buchanan’s A Comparative Vocabulary of Some of the Languages Spoken in the Burma Empire. It is within this survey that the name Rohingya first emerges: “I shall now add three dialects, spoken in the Burma Empire, but evidently derived from the language of the Hindu nation. The first is that spoken by the Mohammedans, who have long settled in Arakan, and who call themselves Rooinga, or natives of Arakan.” (Buchanan & Charney, 2003, p. 55) Published in 1799, Buchanan’s work is the first recording of the endonym Rohingya (Rooinga). Before Buchanan’s work was published, Arakanese Muslims had never been identified in the written record as “Rohingya,” and though there is no absolute evidence as to when and where this endonym first emerged, it should be understood that the Muslims of Arakan discussed above are in fact the same group who would later identify themselves as the Rohingya. Bodawpaya’s rule and that of his successor remained largely unchallenged until the arrival of the British (Yegar, 1972, p. 12). Beginning in 1824, a force led by General Joseph Watson Morrison and another led by Sir Archibald Campbell moved on Arakan, and by 24 February 1826 with the signing of the Treaty of Yandabo, Arakan became a British Territory (Jilani, 2001, pp. 74-75). British control meant stability, and many Rohingya who had fled to Bangladesh began returning to their homes (Bahar, 2010, p. 107; Jilani, 2001, p. 76). As well, Arakan’s first civil ruler under the British, Robertson, encouraged farmers from neighbouring Bengal (Bangladesh) to settle in Arakan so as to increase the production of agricultural commodities for export (Karim, 2000, p. 108). Unfortunately, this movement of Bengali farmers into Arakan obscures the Rohingya’s historical presence in the region, and a number of subsequent events worked to further dispossess the Rohingya of their heritage. The second and third Anglo-Burmese wars saw the whole of Burma come under British rule, and with that Burma was designated as a province of India (Yegar, 1972, p. 29). Large numbers of Indians entered Burma in numbers exceeding 1 million during the British occupation, much to the detriment of the indigenous Rohingya population (Yegar, 1972, p. 31). The colonial tradition of order, quantification and codification meant that the Rohingya became legally categorized as “Indian Muslims” (Bahar, 2010, p. 108), and as such their historical legacy in Arakan was trivialized. Tensions between Burma’s Buddhist and Muslim communities were first exposed in 1930 and again in 1938 with the advent of the “anti-Indian riots” (Bahar, 2010, p. 108). Under colonial rule, many Burmese felt as though they were being dispossessed of their land and that they did not have the same social and economic opportunities as their Indian counterparts. During the riots of 1938, Burmese nationalists warned the colonial government that “steps would be taken…to bring about the extermination of the Muslims and the extinction of their religion” (Yegar, 1972, p. 36) if their concerns were not addressed. Of course, with the Rohingya being understood as Indian Muslims, they were not spared from these sentiments, and it is during this period that their collective persecution had begun to intensify. On 4 January 1948, Burma achieved its independence from Britain and became an independent sovereign state (Tinker, 1967, p. 1) with the British leaving power in the hands of the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). What matters most is that under the leadership of prime minister U 7

- 9. Nu and the AFPFL, the Rohingya were recognized as citizens of Burma (Lay, 2009, p. 57). General Ne Win’s 1962 coup d’état changed all of that however, for Ne Win declared the Rohingya to be “Indian Bengalis” who came to Burma with the British during the first Anglo-Burmese War, a position that has since become the official state line despite its historical inaccuracy (Bahar, 2010, pp. 109-110; Than & Thuzar, 2012, p. 4). Ne Win ordered authorities in Arakan to restrict the Rohingya’s movement, outlawed Rohingya associations and organizations, and cancelled all Rohingya language programming (Jilani, 2002, pp. 70-71). In 1974, the passing of the Emergency Immigration Act informally stripped the Rohingya of their Burmese nationality by supplanting their national registration certificates with foreign registration cards (Cheung, 2011, p. 51; Ahmed, 2010, p. 51). 1978’s Operation Naga Min (Operation Dragon King) was launched to “scrutinize each individual living in the state…taking action against foreigners who [had] filtered into the country illegally” (Oberoi, 2006, pp. 174-175), with the country’s Rohingya population being specifically targeted. This campaign was followed by widespread violence against the Rohingya and some 200,000 fled to Bangladesh (Cheung, 2011; Ullah, 2011; Ahmed, 2010; Oberoi, 2006; Jilani, 2002). On 15 October 1982, the new Citizenship Act was passed rendering the Rohingya officially stateless and placing them outside of Burma’s 135 ethnic groups located within the country’s eight “national races” (Holliday, 2010, p. 118; Parnini, Othman, & Ghazali, 2013, p. 134). In 1990, Operation Pyi Thaya (Operation Prosperous Country) was launched, and the Rohingya were subjected to forced resettlement, forced labour, extortion, torture, rape and killings at the hands of the state, causing another 270,000 refugees to flee to Bangladesh (Oberoi, 2006, p. 180). It would be another twenty years until violence of this degree flared up again, and between June and October 2012 nearly 8,000 Rohingya homes were torched, 31 mosques were destroyed, and 140,000 Rohingya were left displaced in response to reports that 3 Rohingya men had raped a Rakhine woman (Kipgen, 2013, pp. 4-7; International Crisis Group, 2013, p. i). ON STATELESSNESS Statelessness is a contravention of both human dignity and humanity’s inalienable rights. Having a nationality is one of the most basic of rights guaranteed to all members of the human family under the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). As Article 15 of the UDHR states: “(1) Everyone has the right to a nationality;” and “(2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality” (United Nations, 2007). However, in the sixty-six years since the adoption of the UDHR, the inalienable rights espoused by Article 15 have not become universal in scope, and it is currently estimated that there are approximately 12 million stateless peoples worldwide (Staples, 2012, p. ix). This signals an intrinsic deficiency on the part of the UDHR, and one that applies explicitly to the stateless. In her analysis of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, Arendt (1973) argues that the “inalienable” rights of man (human rights) are concomitant with national emancipation, and “whenever people appeared who were no longer citizens of any sovereign state” (p. 293), these supposed rights “proved to be unenforceable” (p. 293). In other words, to be without a state is to exist as “an anomaly for whom there is no appropriate niche in the framework of the general law” (Jermings as cited in Arendt, p. 283, 1973), losing both the legal protection of the state system and an officially recognized identity before the law. Assuming that human rights are in fact inalienable, it would follow that he who has become stateless would be the foremost beneficiary of said rights by virtue of his humanity, but because these rights are contingent on one’s political status as a citizen, “a man who is nothing but a man” (Arendt, 1973, p. 300) loses that which makes it possible for others to treat him as such. Following this logic, nationality is fundamentally “the right to have rights” (van Waas, 2008, p. 217; Weissbrodt, 2008, p. 81). Through the loss of nationality and citizenship, and therefore the means through which any guarantee of human rights can be actualized, the human being is reduced to a state of bare existence, an existence that is itself the ultimate expression of precariousness. 8 Undercurrent Journal Volume XI, Issue I: Fall/Winter 2015

- 10. Though the stateless are placed outside the apparatus of the international state system because of their political non-status, this collective non-status in turn exposes them to all manner of state violence. The reduction to an existence without political status does relieve the stateless of all rights and privileges, but in this process the relationship between the state and the stateless is re-articulated, not abandoned. Agamben (1998) refers to this state of existence as “bare life” (p. 10), wherein “the simple fact of living common to all living beings” (p. 9) is still in fact recognized by the political realm. Central to Agamben’s conception of bare life is an arcane figure derived from Roman law: “homo sacer, (sacred man), who may be killed and yet not sacrificed” (p. 12). Homo sacer represents “a life that may be killed by anyone -- an object of a violence that exceeds the sphere both of law and of sacrifice” (p. 54) for he has been forcibly removed from the political community, reduced to bare life, and placed beyond the protection of divine law as understood by the Romans. Agamben states that in the modern political sphere of national sovereignty “a zone of indistinction between sacrifice and homicide” (p. 53) is formed, and in this sphere the sovereign “is permitted to kill without committing homicide and without celebrating a sacrifice” (p. 53). However, although it has departed from all notions of divinity, the modern system of national sovereignty has retained the figure of homo sacer in that one can be forcibly placed outside the political community, wherein the sovereign is potentially free to kill without transgression. According to Agamben, it is the capture of bare life and homo sacer within the political order on which the entire political system rests. In other words, sovereign power maintains itself in relation to bare life “in an inclusive exclusion” (p. 12), a form of recognition that for Agamben constitutes the nucleus of all sovereign power. Ultimately, the modern sovereign order necessitates the existence of that which it is not to delineate its own existence, creating both the fact of bare life and the conditions in which the unbridled exercise of power over bare life is necessarily sanctioned (Agamben, 1998). Tragically, this is the very situation in which the stateless person is in. When denied one’s citizenship and nationality, the stateless person descends into a state of bare life, unable to secure any semblance of rights, guilty of existence, and confined to and exploited by the very system of which they are no longer a part. Without the right to have rights, the stateless have no means through which they can seek justice, and it is in this space that the state exercises absolute power and control over the stateless. This paradox cannot be overstated, and is repeatedly revealed through the many international instruments designed to provide the stateless with redress. The Rohingya’s descent into a state of bare life and the subsequent tribulation this group encounters are real-world examples of the issues raised by both Arendt and Agamben, and the specificities of their plight will now be outlined in order to proceed. Though the Rohingya were recognized as citizens in Myanmar’s 1948 Constitution (Lay, 2009, p. 57; Yegar, 1972, p. 75), the passing of the 1982 Burma Citizenship Law repealed the Constitution’s attendant Union Citizenship Act that designated the Rohingya as citizens (Aung, 2007, p. 272; Working People’s Daily, 1982). Under the new law, if one were able to provide the state with “conclusive evidence of their lineage” (Ullah, 2011, p. 149) in Myanmar as predating 1823, citizenship would theoretically be granted. However, the aforementioned 1974 Emergency Immigration Act meant that most Rohingya were officially documented as being foreign to Myanmar, and when coupled with repeated flight, internal displacement, and the outright confiscation of identification, the Rohingya were left largely unable to provide documentary evidence of their historical presence in the country. Further, in concert with the passing of this law was the codification of Myanmar’s eight national races (Holliday, 2010, p. 118), in which the Rohingya were not included. As a result, the Rohingya were officially stripped of their Burmese citizenship and the onus was placed on them to prove to the state that they were eligible for one of the three tiers of citizenship. When considering these factors, it can be understood how the Rohingya have been rendered stateless. The particularities of the 1982 Citizenship Law both deny the Rohingya citizenship and prevent them from ever attaining it. Key to all of this is the official state line that the Rohingya are in fact illegal Indian Bengali migrants, a position that prolongs and further entrenches the Rohingya’s collective status as stateless. Even if a Rohingya man or woman were to present conclusive evidence of their historical presence in Myanmar, “those who apply for the [sic] citizenship are subjected to scrutiny by…the Central 9

- 11. Body” (Myanmar President Office, 2013, para. 36), the same Central Body responsible for rendering the Rohingya stateless. Under these circumstances, the granting of citizenship to Myanmar’s Rohingya population amounts to little more than an illusion. Ultimately, the Citizenship Law is a well-crafted encapsulation of the ethno-nationalist vision espoused by the country’s Burman elite, a law that allows for the complete and utter violation of the Rohingya’s human rights. However, there is one mechanism through which the Rohingya can garner legal recognition, and attention must now be placed on the key legal document pertaining to statelessness, the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons. THE RIGHTS OF THE STATELESS Adopted in 1954 and put into force in 1960, the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons is the most comprehensive codification of the rights of the stateless, providing a framework for the international protection of stateless persons (United Nations, 2010). The Convention lays out minimum standards of treatment for those who “qualify as stateless persons” (UN, 2010, p. 3), addressing matters of religion, education, freedom of movement, identity, expulsion, assimilation, and naturalization. Comprised of 42 Articles and grounded in the consideration “that it is desirable to regulate and improve the status of stateless persons by an international agreement” (UN, 2010, p. 5), the Convention currently has 23 signatories and 80 parties, and its enforcement is the responsibility of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (United Nations Treaty Collection, 2014a). Due to their vulnerability, there is obvious need for an international framework to protect the stateless. But, just as human rights fall short of protecting these people, so too does the very convention designed with the intent of protecting them. Evidence of the Convention’s shortcomings first arises in the document’s preamble where it is stated that the rights guaranteed by the Convention are only to be afforded to those who “qualify as stateless persons” (UN, 2010, p. 3). This is problematic because the Convention does not provide guidelines as to how a state should qualify a person as stateless, instead leaving it to the discretion of the state in question. This means that under the guise of the Convention, not only are the stateless burdened with the task of negotiating an inconsistent legal framework, but the prospects for an internationally harmonized approach and solution to the repercussions of statelessness are poor (van Waas, 2008, p. 228). The plight of the stateless is further compounded by Article 7 (1) of the Convention where it is stated that: “Except where this Convention contains more favourable provisions, a Contracting State shall accord to stateless persons the same treatment as is accorded to aliens generally” (UN, 2010, p. 8). However, only those who are lawfully present or lawfully resident are privy to this treatment (van Waas, 2008; Blitz & Lynch, 2011; Staples, 2012). Not only is this is a great difficulty for the person in question in that they must “prove a negative” (Blitz & Lynch, 2011, p. 37) in proving their statelessness, it effectively allows human rights protocols to fall under the discretion of a given state, thereby undermining the purpose of this instrument in its entirety. The 1954 Convention raises another issue, namely that of a “hidden exclusion clause” (Blitz & Lynch, 2011, p. 27). Because states are “free to set the conditions for entry and residence of aliens (Blitz & Lynch, 2011, p. 27), the stateless are at once denied the right to stay and leave, wherein they may become stuck between the sovereign will of two states, spending years in detention (Staples, 2012; Weissbrodt, 2008). Further, not only is it the sovereign right of each state to determine who its citizens are (Staples, 2012, p. 19) the state itself “is constructed through power” (Redclift, 2013, p.33). Key to this power is the state’s capacity “to categorise differently and hierarchically, to set aside by setting apart, and to exclude from state protection” (Redclift, 2013, p. 33). To exercise unconstrained power over the stateless then is a natural expression of state sovereignty, and while it may be at the expense of human dignity (Staples, 2012, p. 18), it is at the very least condoned and in accordance with the same Convention that seeks to uphold the human rights of stateless persons. 10 Undercurrent Journal Volume XI, Issue I: Fall/Winter 2015

- 12. THE CASE OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY Recent developments in and proposed solutions to resolving the Rohingya’s collective statelessness are divided among two camps: what Myanmar can do to end the crisis and what the international community can do to help bring an end to the crisis. This section will address how the international community can help Myanmar move forward. A definite solution to ending the Rohingya’s statelessness will not be proposed. However, by outlining what is happening at the international level, a portrait of what is possible is provided so as to delineate what may or may not happen in the future. Though it was not explicitly concerned with the Rohingya or the issue of statelessness, on 12 January 2007 both the United Kingdom and the United States presented the UN Security Council with a draft resolution on Myanmar (International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect, 2014). The resolution called on the Government of Myanmar to offer unhindered access to humanitarian organizations; to cooperate fully with the International Labour Organization; to make concrete progress towards democracy; and to release all political prisoners (ICRtoP, 2014). The resolution did receive overwhelming support, but China and Russia used their powers to veto the resolution arguing that the violence in Myanmar did not constitute a threat to international peace and security, and that the matter was an internal affair of a sovereign state (Parnini, 2013, p. 291; United Nations Security Council, 2007, para. 4). However, of greater concern is that the notion of state sovereignty was used to prevent international intervention in Myanmar. This is particularly worrying in the sense that sovereignty already provides states with an absolute right to determine who its citizens are. When that same sovereignty is then used to justify violence against a state’s own citizens, let alone against those not recognized by the state, a dangerous precedent is set. The end result is that the stateless are further deprived of having a voice in an international legal framework that essentially condones acts of violence perpetrated against them. Another recent, real-world attempt to resolve the Rohingya issue is the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) adoption of the Bali Process with regard to the Rohingya. During 2009’s 14th ASEAN summit in Thailand (ASEAN, 2012), the Rohingya issue was made a “sideline” concern, kept from the official agenda of the summit but discussed nonetheless (Lay, 2009, p. 58). Leaders of the ASEAN countries agreed the Rohingya issue was of regional concern, and it was brought under the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking and Related Transnational Crime (Ahmed, 2010, p. 133). Rather than falling back on human rights mechanisms embedded within ASEAN’s charter such as Article 1: Section 7’s promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, the Bali Process turns the Rohingya issue into a matter of national security, and as such the human rights and protections needs of the Rohingya are rendered obsolete (Ahmed, 2010, p. 133; ASEAN, 2008, p. 4; Cheung, 2011, pp. 64-65). This move towards the Rohingya as a security issue was later confirmed in October 2012 during the violence that erupted in Rakhine state when Surin Pitsuwan, Secretary General of ASEAN, warned that violence could radicalize the Rohingya and threaten peace and stability in the region (Kipgen, 2013, p. 8). Despite this worrying claim, the Rohingya issue went without mention at two ASEAN ministerial meetings in 2013 (Ganjanakhundee, 2013), and with Myanmar becoming Chair of ASEAN in 2014, it is unlikely the Rohingya will get the attention they deserve from this body. In March 2010, slightly less than a year after ASEAN’s adoption of the Bali Process, UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar Tomas Ojea Quintana called for a UN-mandated commission of inquiry into human rights violations being committed in Myanmar (Parnini, 2013, p. 292). Since making this recommendation, the governments of Australia, Canada, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Hungary, Ireland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Slovakia, the United Kingdom, and the United States have all given their support to the establishment of a commission of inquiry (Parnini, 2013, p. 292). If it were to be completed, ASEAN and other regional governments would then have the increased leverage needed to pressure the Government of Myanmar to make genuine political reforms and end the continued violation of human rights in the country (Parnini, 2013, p. 292). However, during a visit to Rakhine state in August of 2013, Quintana’s presence was met with violent protest (Rohingya Blogger, 2013, para. 4). Such hostilities would not prevent a commission of inquiry from being 11

- 13. completed, but are a worrying indication of the need for such a commission. Since this visit, humanitarian assistance to the Rohingya community in Rakhine state has been temporarily suspended in some regions due to the harassment and intimidation of aid workers, and the blocking of access to camps where internally displaced Rohingya men, women and children are housed (Rohingya Blogger, 2014, para. 8). Again, these events do not mean that a commission of inquiry cannot be established, but signal both the degree of hostility under which such a commission would be carried out and the immediacy with which it must be done. A final real-world example of what has recently been done to resolve the Rohingya issue can be taken from members of the international community who have agreed to resettle documented Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh. Since 2006, a total of 920 recognized Rohingya refugees have been resettled in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Azad & Jasmin, 2013). This is an incredible development, but it is worth considering whether this third country resettlement honours the wishes of Myanmar’s President Thein Sein who has stated that “if there are countries that would accept [the Rohingya], they could be sent there” (UNHCR, 2013, para. 6). Of course, the resettlement of 920 Rohingya between eight countries should hardly be seen as President Sein’s plan coming to fruition, but it does highlight the overwhelming complexity of resolving this issue. As well, it should be noted that only those Rohingya who are recognized as refugees in Bangladesh are permitted to apply for resettlement, and though it is an incredible opportunity to start life anew for those who are eligible, this option falls extremely short of providing a solution for all the Rohingya who are not among those counted by the UNHCR’s operations in Bangladesh. Elsewhere in the international realm, theorists have proposed a variety of solutions to overcome the impasse surrounding the Rohingya issue. Perhaps most radical is Gibney’s (2013) discussion of extraterritorial obligations, an approach that mirrors the Responsibility to Protect. Through this approach, the international community assumes the task of protecting the economic, social and cultural rights of persons when the state is unable or unwilling to do so. However, the problem with Gibney’s approach is threefold. First, moral obligations may very well be used as a pre-text for military intervention. Second, the Extraterritorial Obligations Human Rights Consortium (ETO) charged with promoting these principles only published said principles in 2013. Lastly, these principles may amount to little more than another list of rules to be followed, or not. CONCLUSION Reverting back to this thesis’ introduction, it is quite apparent that the suffering of the Rohingya has continued to escalate despite a multitude of international instruments designed to offer stateless peoples redress, and though evidence of the desperate conditions under which the Rohingya live is widely available, the international community is both unwilling and unable to act. As we have seen, the Rohingya have a long history in what is now Myanmar’s Rakhine state, at one time claiming the same soil as the independent kingdom of Arakan. In 1982, Burmese nationalists were successful in stripping the Rohingya of their Burmese citizenship, and in so doing rendered the Rohingya non-citizen resident foreigners. Since this time, the Rohingya’s legal non-status has effectively enabled the perpetration of human rights violations against them, and tragically, with no resolution in sight. To be sure, there have been international efforts to bring an end to the displacement and human rights violations the Rohingya seem almost destined to endure. Yet, those actors who have sought to address human rights violations have only been able to secure non-binding resolutions or have had their efforts impeded by the all-encompassing rhetoric of statelessness’ troubling bedfellow, sovereignty. Still, the most pressing matter is the denial of the right to a nationality, the key human rights violation experienced by the Rohingya. So as long as it is the sovereign right of each state to determine who its citizens are, there is absolutely no reason for Myanmar or any other country to include the 12 Undercurrent Journal Volume XI, Issue I: Fall/Winter 2015

- 14. Rohingya as part of its national community. Tragically, state sovereignty also reduces the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons to little more than paper tigers, and when the most comprehensive legal documents pertaining to the rights of the stateless are neutralized, an impasse on how to address statelessness takes hold. The recent resettlement of Rohingya refugees to various Western nations has provided those fortunate enough to be classified as refugees and selected for resettlement with a future they would have otherwise been unable to secure. However, this could be invoked to justify the Burmese Government’s calls for third country resettlement, and should be approached with caution. As both Arendt (1973) and Agamben (1998) have shown, sovereignty ultimately trumps any attempt to remedy statelessness. Citizenship is the right to have rights, and once it has been lost the stateless have no means of pursuing legal recourse for any affront committed against them. In other words, once one is not recognized as the national of any state, they are afforded no guarantees by the state and yet are exposed to all manner of violence and control by the state. This is how sovereignty is ultimately actualized. It is in this space that the Rohingya dwell, made to be everyone’s concern yet no one’s responsibility, and as long as our current conception of sovereignty persists, so too will the statelessness of the Rohingya. 13

- 15. REFERENCES Agamben, G. (1998). Homo Sacer. Sovereign power and bare life. California: Stanford University Press. Ahmed, I. (2010). The plight of stateless Rohingyas: Responses of the state, society & the international community. Dhaka: The University Press. Arendt, H. (1973). The origins of totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company. ASEAN. (2008). The ASEAN Charter. Retrieved from http://www.asean.org/archive/publications/ASEAN- Charter.pdf ASEAN. (2012). Fourteenth ASEAN Summit, Thailand, 26 February - 1 March 2009. Retrieved from http:// www.asean.org/news/item/fourteenth-asean-summit-thailand-26-february-1-march-2009 Aung, T. T. (2007). An introduction to citizenship card under Myanmar citizenship law. Modern Cultural Studies Society, 38(3), 265-290 Azad, A., & Jasmin, F. (2013). Durable solutions to the protracted refugee situation: The case of Rohingyas in Bangladesh. Journal of Indian Research, 1(4), 25-35. Bahar, A. (2010). Burma’s missing dots: The emerging face of genocide. Bloomington: Xlibris Corporation. Blitz, B. K., & Lynch, M. (2011). Statelessness and citizenship: A comparative study on the benefits of nationality. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Buchanan, F., & Charney, M. W. (2003). A Comparative Vocabulary of Some of the Languages Spoken in the Burma Empire. School of Oriental and African Studies Bulletin of Burma Research, 1(1), 40-57. Cheung, S. (2011). Migration control and the solutions impasse in South and South East Asia: Implications from the Rohingya experience. Journal of Refugee Studies, 25(1), 50-70. Ganjanakhundee, S. (2013, August 2014). No takers yet for the Rohingya. The Nation. Retrieved from http://www.nationmultimedia.com/politics/No-takers-yet-for-the-Rohingya-30212551.html Gibney, M. (2013). Establishing a social and international order for the realization of human rights. In L. Minkler (Ed.), The state of economic and social human rights: A global overview (pp. 251-270). New York: Cambridge University Press. Holliday, I. (2010). Ethnicity and democratization in Myanmar. Asian Journal of Political Science, 18(2), 111-128. International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect. (2014). Burma Resolution in Security Council, vetoed by Russia and China: Implications for RtoP. Retrieved from http://www.responsibilitytoprotect.org/index.php/crises/128-the-crisis-in-burma/793-burma- resolution-in-security-council-vetoed-by-russia-and-china-implications-for-r2p International Crisis Group. (2013). The Dark Side of Transition: Violence Against Muslims in Myanmar (Asia Report No. 251). Retrieved from International Crisis Group: http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/ regions/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/251-the-dark-side-of-transition-violence-against- muslims-in-myanmar.aspx Jilani, A. F. K. (2001). A cultural history of Rohingya. Dhaka: Ahmed Jilani. Jilani, A. F. K. (2002). Human rights violations in Arakan. Chittagong: The Taj Library. Karim, A. (2000). The Rohingyas: A short account of their history and culture. Chittagong: Arakan Historical Society. Kipgen, N. (2013). Conflict in Rakhine state in Myanmar: Rohingya Muslims’ conundrum. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 33(2), 298-310. Lay, K. M. (2009). Burma fuels the Rohingya tragedy. Far Eastern Economic Review, 172(2), 57-59. Myanmar President Office. (2013). Immigration & Population Ministry clarifies over “the government is planning to amend the 1982 Myanmar Citizenship Law” covered by the Daily Eleven Newspaper. Retrieved from http://m.president-office.gov.mm/en/?q=issues/civil-right/id-2228 Oberoi, P. A. (2006). Exile and belonging: Refugees and state policy in South Asia. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Parnini, S. N. (2013). The crisis of the Rohingya as a Muslim minority in Myanmar and bilateral relations with Bangladesh. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 33(2), 281-297. Parnini, S. N., Othman, S. H., & Ghazali, A. S. (2013). The Rohingya refugee crisis and Bangladesh- Myanmar relations. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 22(1), 133-146. 14 Undercurrent Journal Volume XI, Issue I: Fall/Winter 2015

- 16. Redclift, V. (2013). Statelessness and citizenship: Camps and the creation of political space. Oxon: Routledge. Rohingya Blogger. (2013). US envoy says Myanmar failed to protect him in attack [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://www.rohingyablogger.com/2013/08/un-envoy-says-myanmar-failed-to- protect.html Rohingya Blogger. (2014). Quintana plans visit in midst of anti-UN protests [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://www.rohingyablogger.com/2014/02/quintana-plans-arakan-visit-in-midst-of.html Staples, K. (2012). Retheorising statelessness: A background theory of membership in world politics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Than, T. M. M., Thuzar, M. (2012). Myanmar’s Rohingya dilemma. Institute of South East Asian Studies – perspective, 1. Retrieved from http://www.iseas.edu.sg/documents/publication/ISEAS %20Perspective_1_9jul121.pdf The Sentinel Project for Genocide Prevention. (2013). Burma risk assessment (September 2013). Retrieved from http://www.thesentinelproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Risk- Assessment-Burma-September-2013.pdf Tinker, H. (1967). The Union of Burma: A study of the first years of independence. London: Oxford University Press. Ullah, A. A. (2011). Rohingya refugees to Bangladesh: Historical exclusions and contemporary marginalization. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 9, 139-161. United Nations. (2007). Universal Declaration of Human Rights: 60th Anniversary Special Edition, 1948-2008. New York: United Nations Department of Public Information. Retrieved from EBSCOhost database. United Nations. (2010). Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons. Retrieved from United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: http://www.unhcr.org/3bbb25729.html United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2013, December 7). Call to put Rohingya in refugee camps. Refugees Daily. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/refdaily? pass=463ef21123&date=2012-07-13&cat=Asia/Pacific United Nations Security Council. (2007). Security Council fails to adopt draft resolution on Myanmar, owing to negative votes by China, Russia Federation. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/News/ Press/docs/2007/sc8939.doc.htm United Nations Treaty Collection. (2014a). Chapter V: Refugees and stateless persons. Retrieved from https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetailsII.aspx? &src=UNTSONLINE&mtdsg_no=V~3&chapter=5&Temp=mtdsg2&lang=en van Waas, L. (2008). Nationality matters: Statelessness under international law. Antwerp: Intersentia. Weissbrodt, D. (2008). The human rights of non-citizens. New York: Oxford University Press. Working People’s Daily. (1982, October 16). Burma citizenship law. Working People’s Daily. Retrieved from http://www.ibiblio.org/obl/docs/Citizenship%20Law.htm Yegar, M. (1972). The Muslims of Burma: A study of a minority group. Germany: Otto Harrasowitz, Wiesbaden. 15

- 17. “Africa Rising”: A Hopeless Falsity or a Hopeful Reality? By: Hannah Hong Abstract - According to The Economist and mainstream literature, two opposing narratives of Africa exist in relation to its development: the long-standing view of Africa as “The Hopeless Continent” and the recent emergence of an “Africa Rising,” as presented by The Economist covers in 2000 and 2011.This paper argues that both dominant narratives are “single stories” that work to conceal problematic inequalities and injustices that are increasing at the expense of growing economies (Adichie, 2009, para. 10) An analytical case study of Rwanda and its acclaimed post-genocide success is presented to discuss the significant issues of inequality, poverty, and power in African countries that are often obscured by the rhetoric of thriving development and the idea that Africa is rising. Résumé - Selon The Economist et la littérature dominante, deux récits opposés de l’Afrique existent en ce qui concerne son développement : la vision de longue date de l’Afrique en tant que « le continent désespéré » et l’émergence récente d’une « Afrique montante », comme le présentent les couvertures de The Economist en 2000 et 2011. Ce papier soutient que tous les deux récits sont des «histoires uniques » qui cherche à cacher des inégalités problématiques and des injustices qui augmentent aux détriment des économies croissantes (Adichie, 2009, para. 10). Une étude analytique de cas du Rwanda et son succès acclamé post-génocide est présenté pour discuter les enjeux importants de l’inégalité, la pauvreté et la puissance dans les pays africains, ceux qui sont souvent obscurcis par la rhétorique du développement florissant et l’idée que l’Afrique est en train de monter. In 2000, The Economist cover presented Africa as “The Hopeless Continent.” In 2011, the same journal cover presented the continent as “Africa Rising.” These opposing representations indicate the occurrence of a recent transformation of the image of Africa into one of a burgeoning victory with its increasing integration into the global political-economic sphere. Africa is certainly no longer regarded as hopeless. Nevertheless, today’s simplified vision of “Africa Rising” is a clear example of what Chimamanda Adichie (2009) describes as a “single story” (para. 10). According to Adichie (2009), a “single story” is one that becomes the definitive story for a certain place or group of people and leads to critical misunderstandings and misconceptions. The rhetoric of “Africa Rising” presents an inaccurate “single story” of Africa that highlights certain realities of recent success and simultaneously obscures problematic realities that persist. It is necessary to examine the notion of hope as well; although problematic realities should be addressed, a lack of response does not necessarily negate hope that exists for the future. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this paper, hope will be regarded as positive expectations and aspirations for the future, specifically for the people living in the countries of Africa. This paper will argue that Africa in the 21st century can be regarded as hopeful if local, national, and global communities look beyond the “single story” paradigm in order to address deep-rooted problems within the contemporary development framework. This paper will also discuss recent problems regarding poverty and power in the general context of Africa and in the specific case of the country of Rwanda. For centuries, the continent of Africa has been dominated by an ongoing narrative and image of poverty, conflict, primitivism, and dependency. The overused term, “Africa,” itself as a referent for any individual African country suggests a sense of uniformity of this “hopeless” condition across all of its historically, politically, ethnically, and culturally diverse countries. In Mazrui’s (2005) discussion of the various “inventions” of Africa throughout history, he identifies Europe’s “Africanization” of the continent as the most dominant and persistent invention. Europeans drew from the Orientalist understanding of “the Other,” who is characterized as “exotic, intellectually retarded, emotionally sensual, governmentally despotic, culturally passive, and politically penetrable,” in order to define the people and continent of Africa as a whole and assert Western power, and superiority over them (p. 69). Adichie (2009) argues that the danger of a “single story” is created through the repetition of one story until it dominates as the only 16 Undercurrent Journal Volume XI, Issue I: Fall/Winter 2015

- 18. story. Moreover, she argues that “single stories” ultimately stem from the issue of power: “Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story” (Adichie, 2009, para. 19). The “single story” of Africa has led to narrow stereotypes that reduce the diversity and complexity of the continent to particular histories and realities, obscuring the rest in its entirety. Smith (2003) identifies two recurring single stories of Africa today: Afro-pessimism and Afro- optimism (p. 9). These two narratives are evident in the juxtaposition of the contrasting covers of The Economist. Afro-pessimism is characterized by the long-standing view of Africa as a hopeless continent. Afro-optimism is present in the recent rhetoric of “Africa Rising,” which emphasizes the emergence of democracies, social movements, civil societies, new development initiatives, and various countries’ integration into the global economic sphere (Smith, 2003, p. 21). Despite its refreshing positive outlook on Africa, the notion of “Africa Rising” is an equally dangerous “single story” of the continent that obscures several problematic realities that continue to persist. Africa’s economic growth in this era of globalization is certainly a positive occurrence that must be acknowledged. Statistics showed that seven of the ten fastest growing economies between 2011 and 2015 would most likely be African countries (Chimhanzi, 2012, p. 503). Other advances include increased foreign investment, growing access to technology, growing urbanization, new oil and gas resources, and higher education rates (Slattery, 2013, p. 88). It is important to note that much of Africa’s progress has been fueled by neo-liberal agendas and policies. Neo-liberalism is an economic and political ideology in which market capitalism is hailed as the most effective way to achieve modernization, development, and prosperity for all. Its three major tenets are privatization, free markets, and deregulation. (Harrison, 2005, p. 1305). Despite today’s deepening inequality in the world, the neo-liberal ideology claims that everyone will benefit from market expansion due to the “trickle-down” effect (M. Levin, personal communication, January 23, 2014). Moreover, Harrison (2005) characterizes neo-liberalism, not only as an agenda to expand the market and remove the government from the economy, but also a project to shape the economy, state, and society (p. 1306). In the vast majority of the African continent, The World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) have played a key role in this process by imposing neo-liberal agendas through lending conditionalities for aid recipient countries, funding packages, and policy development and procedures since the 1980s (Harrison, 2005, p. 1309-1311). The recent notion of “Africa Rising” and neo-liberalism as compulsory counterparts presents the contemporary “single story” of Africa. In order to have legitimate hope for Africa’s future, it is necessary to examine this single story and ask: who holds the power to maintain this narrative? Who are the winners and losers? Where is it being reproduced and why? Which stories are being obscured? The answers to these questions are different for every individual country with its specific context and history. The following analysis investigates these questions in a broader scope with regard to the continent’s recent economic growth. While neo-liberalism has been extolled as the driver of Africa’s increasing economic and developmental prosperity, the idea of “Africa Rising” obscures other realities that also exist alongside the growth of market capitalism. Despite its increasing integration into the global market, sub-Saharan Africa remains in an uneven balance of trade relations that are heavily dependent on other countries and a few commodities. Moreover, countries with rising economies, such as South Africa, make up some of the most unequal societies in the world according to data from the Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality based on GDP and distribution (M. Levin, oral presentation, January 30, 2014). The international community and the United Nations (UN) recognized these inequalities and the progress that has yet to be made; in 2000, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were created to establish focused targets for development and poverty alleviation to be achieved by 2015. Despite the enormous progress reported by the UN, the language of the MDGs, which focuses on poverty in terms of percentage of population, fails to acknowledge the continued growth of poverty in actual numbers, as well as the uneven distribution of this progress across socio-economic classes. Brikci and Holder (2010) analyze the progress of MDG4, which aims to reduce the under-five mortality rate by two-thirds by 2015; they argue that the MDGs have failed to consider equity issues and specify which groups would be 17

- 19. benefiting from these efforts. In other words, the MDGs could be achieved by benefiting the wealthy and further marginalizing the poor, and national governments have been praised for their progress in development regardless of such inequalities (Brikci & Holder, 2010, p. 75). Brikci and Holder’s (2010) study reports that sub-Saharan Africa accounted for the highest levels of under-five mortality in 2007, indicating the globally uneven distribution of the benefits of MDG4 (p. 80). These realities have been obscured by the emergence of the single story of “Africa Rising.” Rwanda is one country that has been acclaimed as a success story in economic and developmental growth since the Rwandan genocide of 1994. It is one of the countries that have made the greatest progress in lowering mortality rates since the formation of the MDGs in 1990 (Brikci & Holder, 2010, p. 83-84). The World Bank and IMF have praised Rwanda for its thriving economy and significant advancements in technology and development, in accordance with the MDGs (Ansoms & Rostagno, 2012, p. 428). Rwanda is a valuable country for analysis for three reasons: first, Rwanda exemplifies the “single story” of “Africa Rising” in its own narrative of ascendancy and success in the post-genocide era. Second, the nature of its growth and development has been executed in accordance with the neo-liberal agendas of the World Bank and IMF, as well as the MDGs. Third, a closer investigation of the consequences of these actions and current realities reveals a range of stories and perspectives that have been concealed by Rwanda’s mainstream success story narrative. Thus, the following analysis of this country will substantiate the argument that Africa’s hope lies within its potential to delve into an analytic framework that questions the dominant “single stories” of Africa and seeks to reveal the uncomfortable truths that have been overlooked. It is essential to acknowledge that the very discussion and analysis of Africa as a whole perpetuates the “single story” of Africa, regardless of the perspective: every country has an individualized and unique case regarding its social and economic issues. While maintaining this awareness, this paper attempts to examine certain patterns of events over the recent years, using evidence from specific countries, in order to challenge the uncritical, homogenized single story of Africa. Rwanda’s “single story” of success appears to be genuine and hopeful in many ways. Indeed, Rwanda has accomplished great successes in rebuilding its economy, infrastructure, and society after the tragedies of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. In the two decades following the genocide, the Rwandan government has established and worked towards specific developmental goals, outlined in Rwanda’s Vision 2020 document and the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) (Government of Rwanda, 2009). According to the Government of Rwanda (2009), the aim of Vision 2020 is to “transform Rwanda into a middle-income country by the year 2020” (as cited in Ansoms & Rostagno, 2012, p. 430). In macroeconomic terms, Rwanda is well on its way to achieving this goal. The IMF (2011) reports that the country has reached an average annual economic growth rate of eight percent, which is in line with the goals of Vision 2020 (as cited in Ansoms & Rostagno, 2012, p. 428). The UN Development Programme (2007) has also declared Rwanda an exemplary country that is likely to reach the MDGs and “showcase the potential of the new Post-Millennium Declaration” (as cited in Ansoms & Rostagno, 2012, p. 428). With regard to the PRSPs, poverty in Rwanda has decreased by 12 percent between 2005/6 to 2010/11 (p. 428). The country has also made significant strides in internet and mobile phone technology, which has aided further development and poverty-reducing strategies. For example, the e-Soko project, designed by the Rwandan Ministry of Agriculture in 2011, provides market price information to rural farmers and farming cooperatives via mobile phones, which gives them immediate access to determine better prices at which to sell their goods (Vrakas, 2012, p. 84). Such technological developments support President Paul Kagame’s goal to develop the country’s autonomy and push Rwanda to become a worthy player in the global economic sphere. The progress Rwanda has made thus far has been met with praise from the international community. However, these success stories conceal several problems in the country that persist and worsen. In order to move the country forward in a hopeful direction, it is necessary to address the realities that this single story excludes. Two major issues have emerged with Rwanda’s success: institutional land reforms and Kagame’s leadership and government. The first problem, which has emerged with globalization and Rwanda’s adherence to the neo- liberal agenda, concerns small-scale agriculture and its conflicts with land reforms. The Rwandan 18 Undercurrent Journal Volume XI, Issue I: Fall/Winter 2015

- 20. government has worked towards transforming their primarily subsistence agriculture-based country to a modern sector service-driven country that is competitive in the global economy. However, small-scale farmers and peasants have faced radical unforeseen changes and sudden dispossession of their land as a result of the government’s considerable investments in land reforms (Oxresearch Daily Brief Service, 2010). One practice that has been imposed by the government is monocropping, in which farmers cultivate only one crop per plot; this crop is designated by local authorities in accordance with market demands (Ansoms, 2010, p. 106-107). It is important to note that monocropping was also imposed by Belgian administrators during the colonial era, which demonstrated the power of the elites and resulted in disastrous agricultural results for the peasant population (Ansoms, 2010, p. 107). Similarly, in Ansoms’s (2010) interviews, local farmers mentioned the various disadvantages to monocropping, such as decreased soil fertility with lack of crop rotation, increased vulnerability to disease and weather fluctuations, and thus, the elimination of farmers’ financial and livelihood insurance (p. 108). Although land reforms are part of the government’s effort to transform Rwanda into a more modern, developed society, this top-down approach reveals the ways in which the government ultimately holds and exercises its power over the people, and, in this case, disregards the exacerbated poverty of rural farmers. Swampland reorganization is another government intervention that has taken place for agricultural reforms; land laws declared all swamplands as state property and the government assumed the role of swampland developer (Ansoms, 2010, p. 111). In these restoration projects, financial and agricultural considerations for poorer groups were completely excluded, and thousands of small-scale peasants were dispossessed without any compensation (Ansoms, 2010, p. 111-113). Ansoms’s (2010) case studies and interviews clearly show that, despite the implementation of PRSP policies to reduce poverty, the Rwandan government has failed to consider the real negative consequences of institutional actions at the local level. The World Bank (2007) reports assume that small-scale agriculture is inefficient and unviable with the continuing spread of the free market (as cited by Ansoms, 2013, p. 16). The Rwandan government’s objectives and policies conform to these neo-liberal beliefs; they ultimately favour local elites and the government and further deepen the poverty of poorer populations. These problems must be acknowledged and addressed by the government and the people in order for the country to move forward in a hopeful direction. Ansoms (2013) proposes increased facilitation of connections between small-scale farmers and intermediary local officials as one possible step to mitigate the problems of current land reforms. President Kagame has been another focal point of the country’s single story of success. Desrosiers and Thomson (2011) argue that public speeches and presentations of benevolent leadership hold a significant influence over a country’s development: “They reflect choices made by political leaders as to how to present and position themselves in relation to the international community, especially neighbors, donors, and allies, and to Rwandans. As rhetorical artifices, these images and projections rarely accurately mirror reality, but instead, embellish or disguise it.” (p. 437) Kagame’s use of a national rhetoric and the vision of a new Rwanda conceals the fact that many of its policies perpetuate poverty, deprive certain groups of their livelihoods, and ultimately allow for the government to exercise their power for their own benefit while disregarding disadvantaged populations. Land reforms serve as one illustration of this problem; another case of this issue is present in Kagame and the Rwandan government itself. According to a survey of 60 foreign policy experts, Kagame was voted as Africa’s most effective political leader (Slattery, 2013). However, Desrosiers and Thomson (2011) and other scholars agree that post-genocide Rwanda is less reflective of a democracy and more reflective of an authoritarian dictatorship with little regard for human rights and welfare for its large peasant population (p. 438). In fact, the nation has been under the rule and power of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) since the end of the genocide in July 1994, and Kagame has failed to acknowledge or bring to justice the crimes that were committed by the RPF before, during, and after the genocide (Desrosiers & Thomson, 2011, p.447). Moreover, critical and opposing voices have been systematically 19

- 21. silenced by the RPF government (p. 438). Kagame won the presidential election with 95 percent of the votes in 2003 and 93 percent in 2010; Human Rights Watch and other sources believe these elections were skewed by “intimidation, exclusion of the opposition and critical voices, and a climate of fear” (Naftalin, 2011, p. 23). Nevertheless, Kagame’s government has been able to reign for two decades by rejecting the country’s colonial, ethnic, and violent past and proposing a new Rwanda, parallel to the “single story” of “Africa Rising,” which points to a new era of good governance, peace, and development (Desrosiers & Thomson, 2011, p. 444). The government focused heavily on national unity and reconciliation during the post-genocide years to move towards ethnic solidarity built upon the Rwandan identity; Kagame established the pride and identity of Rwandans by insisting that the development of the country must be carried out by the Rwandans themselves (Desrosiers & Thomson, 2011, p. 445). This top-down rhetoric of the new Rwanda, national pride, empowerment, and hope unfortunately works to suppress the stories that exist at the local and individual levels. Despite Kagame’s presentation of strong leadership that cares deeply about the development of all the people of Rwanda and the international acclaim Rwanda has received for its progress, the country’s poverty statistics present a different reality (Ansoms, 2010, p. 99). As previously mentioned, poverty rates have decreased significantly since the implementation of the PRSP policies; however, in numbers, poverty increased from 4.8 to 5.4 million people between 2001 and 2006 (Ansoms, 2010, p. 99). In the same years, Rwanda’s Gini coefficient increased from 0.37 to 0.44, indicating that Rwanda’s successes have been unevenly distributed, deepening inequalities in the population (Ansoms, 2010, p. 99). Kagame’s government significantly contributed to these numbers by imposing development policies that further marginalize peasant populations. While the UN Development Programme praised Rwanda for its economic growth, their 2010 report notes that the country is unlikely to achieve the goal to eradicate extreme poverty by 2015 because its growth is concentrated within Rwanda’s small elite class (Ansoms & Rostagno, 2012, p. 428). The same situation is evident in the African continent as a whole. While the World Bank (2005) claims that many countries in Africa are “turning the corner” with regard to the MDGs, statistics reveal that sub-Saharan Africa is substantially behind in achieving its targets (as cited in Hayman, 2007, p. 379). The World Bank’s interpretation of economic growth is fundamentally based on neo-liberal principles, which ignore the issue of equity, as demonstrated by the case study of Rwanda. In West Africa, Angola is another country that has risen in economic growth and power; however, 43 percent of its population was undernourished in 2007 (M. Levin, oral presentation, January 30, 2013). Similarly, Mozambique has also been praised by the World Bank and IMF for its economic progress and its adherence to the neo-liberal agenda in liberalizing their resource sectors; the country also has approximately 52 percent of its population living in poverty and a low rank of 184 out of 187 countries on the UN’s Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index in 2011 (as cited in Silva, 2013, p. 24). Thus, while varying factors and contexts differentiate each country, an overarching pattern emerges across many of Africa’s diverse countries. An examination of Africa as a whole and Rwanda as a specific case study reveals that The Economist’s cover of “Africa Rising” is indeed a truth that has occurred and is continuing to occur on the continent. Businesses and economies are booming, growth rates are increasing, and development is progressing. However, this paper has argued that “Africa Rising” is also a “single story” that obscures several problematic issues that remain, including those of poverty, power, and inequality. In order to regard Africa as a hopeful continent, we must acknowledge the power and danger of the “single story”. Analyses of the economic growth and success stories of Africa and its countries must assume an analytic framework by asking critical questions: Who is benefiting? How are these processes unfolding? Where is power located, and how are people’s lives being impacted? The first step involves interrogating the dominant perspective and uncovering the obscured realities that exist alongside the single story. From here, we may develop appropriate solutions and strategies to work towards a hopeful future. 20 Undercurrent Journal Volume XI, Issue I: Fall/Winter 2015

- 22. REFERENCES Baranyi, S. & Desrosiers, M. (2012). Development and cooperation in fragile states: Filling or perpetuating gaps? Conflict, Security & Development, 12(5), p.443-459. Baranyi, S. & Paducel, A. (2012). Whither development in Canada’s approach to fragile states? In S. Brown (Ed.), CIDA and Canadian Aid Policy. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. BBC. (2011, February 8). Hamid Karzai says Afghanistan aid teams must go. Retrieved March 21, 2013 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-12400045. Beal, J., Goodfellow, T. & Putzel, J. (2006). Introductory Article: On the Discourse of Terrorism, Security and Development. Journal of International Development, 18(1), p.51-67. Bollen, M., Linssen, E. & Rietjens, S. (2006). Are PRTs supposed to compete with terrorists? Small Wars and Insurgences, 17(4), p.437-448. Buzan, B., Weaver, O. & de Wilde, J. (1997). Security: A new framework for analysis. Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers Inc. Coombes, H. (2012). Canadian whole of government operations, Kandahar, September 2010-July 2011. The Conference of Defense Associations Institute: Ottawa. Davidson, J. (2009). Principles of modern American counterinsurgency: Evolution and debate. The Brookings Institution: Counterinsurgency and Pakistan Paper Series. Retrieved February 26, 2013 from http://www.brookings.edu/about/programs/foreign-policy/counterinsurgency-and-pakistan- paper-series. DFATD. (2013). Baird reaction to John Kerry statement on Syria. Retrieved August 31, 2013 from http:// www.international.gc.ca/media/aff/news-communiques/2013/08/30a.aspx. Duffield, M. (2001). Introduction. In Global governance and the new wars: The merging of development and security (p.1-21). New York: Zed Books. Fukuyama, F. (2004). The Imperative of State-Building. Journal of Democracy, 15(2), p.17-31. Government of Canada. (2012). Canada’s engagement in Afghanistan: Fourteenth and final report to parliament. Forward. Retrieved March 21, 2013 from http://www.afghanistan.gc.ca/canada- afghanistan/documents/r06_12/for-ava.aspx?lang=eng&view=d. Holland, K. (2010). The Canadian provincial reconstruction team: The arm of development in Kandahar province. American Review of Canadian Studies, 40(2), p.276-291. IRIN. (2011, April 13). Afghanistan: Volatile Kandahar - the polio capital. Retrieved March 21, 2013 from http://www.irinnews.org/Report/92454/AFGHANISTAN-Volatile-Kandahar-the-polio-capital. Jervis, R. (1976). Perception and misperception in international politics. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Kells, B. (2011). Aid effectiveness in Afghanistan: The Canadian provincial reconstruction team. Unpublished paper. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON. NATO. (n.d.). About ISAF: Troop numbers and contributions. Retrieved February 26, 2013 from http:// www.isaf.nato.int/troop-numbers-and-contributions/index.php. NATO. (2003). NATO civil-military co-operation (CIMIC) doctrine. Retrieved March 20, 2013 from http:// www.nato.int/ims/docu/ajp-9.pdf. OECD. (2005). The Paris declaration for aid effectiveness. Retrieved February 26, 2013 from http:// www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/34428351.pdf. OECD. (2007). Principles for good international engagement in fragile states & situations. Retrieved March 21, 2013 from http://www.oecd.org/dac/incaf/38368714.pdf. OECD. (2010). Monitoring the principles for good international engagement in fragile states and situations: Country report 1: Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Retrieved March 21, 2013 from http://www.oecd.org/dacfragilestates/44654918.pdf. OXFAM. (2010). Quick impact, quick collapse: The dangers of militarized aid in Afghanistan. Retrieved March 20, 2013 from http://www.oxfam.org/en/policy/quick-impact-quick-collapse. Perito, R., Abbaszadeh, N., Crow, M., El-Khoury, M., Gandomi, J., Kuwayama, D., . . . Weiss, T. (2008). Provincial reconstruction teams: Lessons and recommendations. Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://wws.princeton.edu/research/pwreports_f07/wws591b.pdf. Rid, T. & Keaney, T. (2010). Understanding counterinsurgency: Doctrine, operations, and challenges. New York: Routledge. 21

- 23. Shannon, R. (2009). Playing with the principles in an era of securitizing aid: Negotiating humanitarian space in post-9/11 Afghanistan. Progress in Development Studies, 9(1), p.15-36. The Fund for Peace. (2013). Failed states index: 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013 from http:// ffp.statesindex.org/rankings-2013-sortable. US Marine Corps. (2006). FM 3-24: Counterinsurgency. Retrieved February 26, 2013 from http:// www.fas.org/irp/doddir/army/fm3-24.pdf. Valentino, B., Huth, P., & Balch-Lindsay, D. (2004). “Draining the sea”: Mass killing and guerilla warfare. International Organization, 58(2), p.375-407. Walther, H. (2007). The German concept for provincial reconstruction teams. Retrieved March 21, 2013 from http://www.cdef.terre.defense.gouv.fr/publications/doctrine/doctrine13/version_us/etranger/ art8.pdf. Waltz, K. (1988). The origins of war in neorealist theory. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 18(4), p. 615-628. 22 Undercurrent Journal Volume XI, Issue I: Fall/Winter 2015