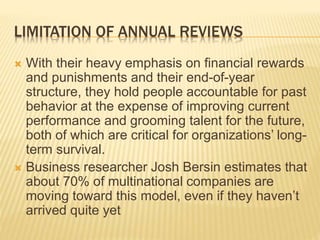

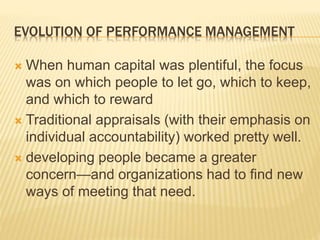

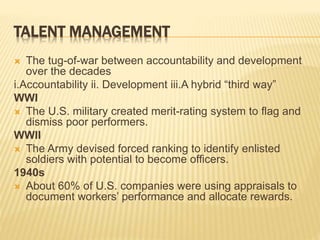

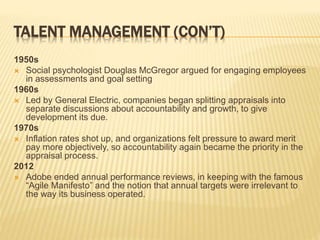

The document discusses how many companies are moving away from annual performance reviews and toward more frequent, informal check-ins between managers and employees. It argues that annual reviews primarily focus on accountability for past performance rather than improving current performance or developing future skills. Some of the benefits cited for less formal check-ins include prioritizing employee development, promoting agility in fast-changing business environments, and enhancing teamwork. However, challenges remain in aligning goals, rewarding performance, and managing feedback without traditional review systems.