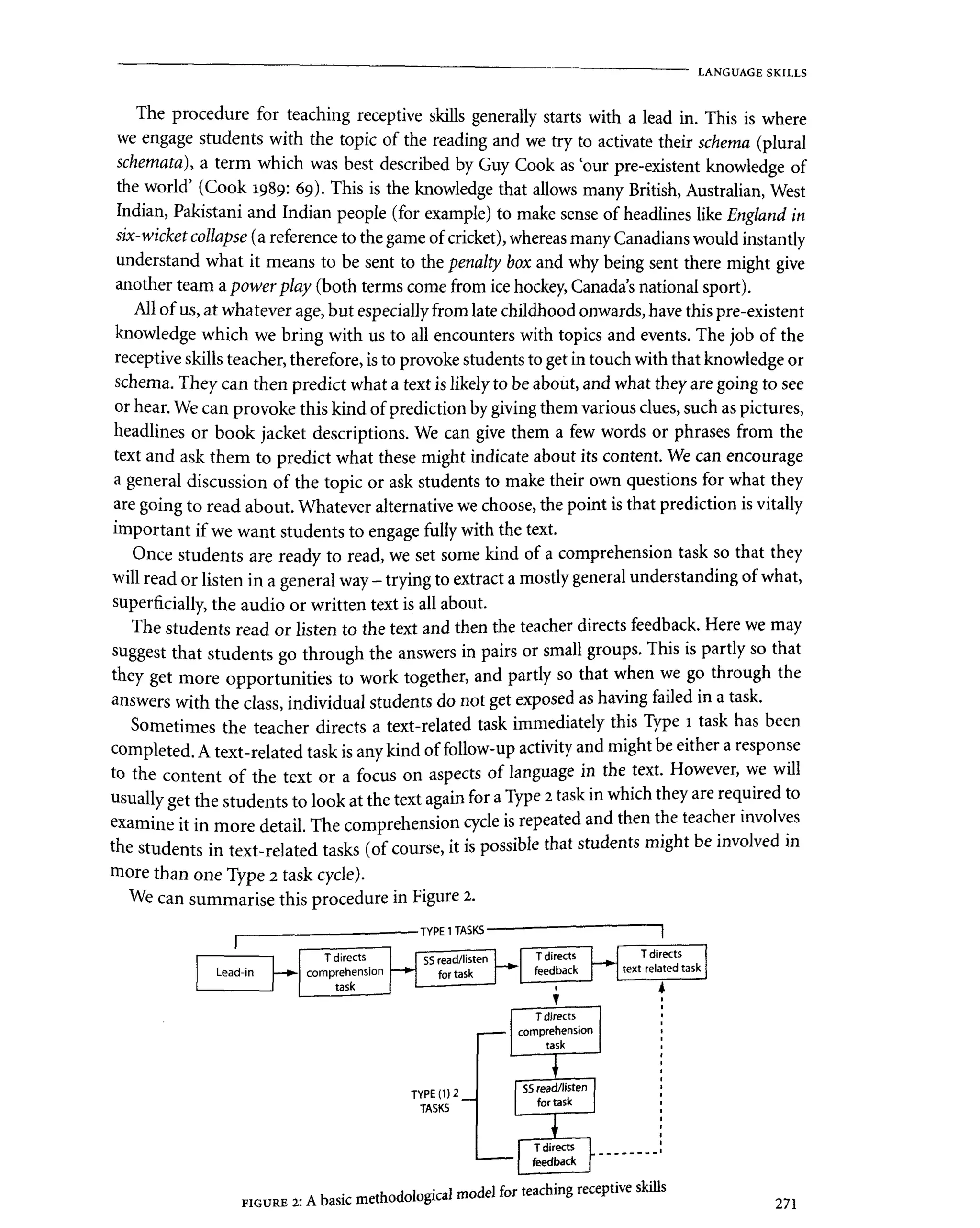

The document discusses methods for teaching receptive language skills like reading and listening. It describes a basic procedure that teachers often use which involves both general (Type 1) comprehension tasks and more detailed (Type 2) tasks. For Type 1 tasks, students read or listen for overall understanding rather than details. This allows them to get a sense of the text before analyzing it in more detail. The document also discusses factors that influence text difficulty, the benefits of extensive reading and listening, and how to choose comprehension tasks that promote understanding rather than testing.