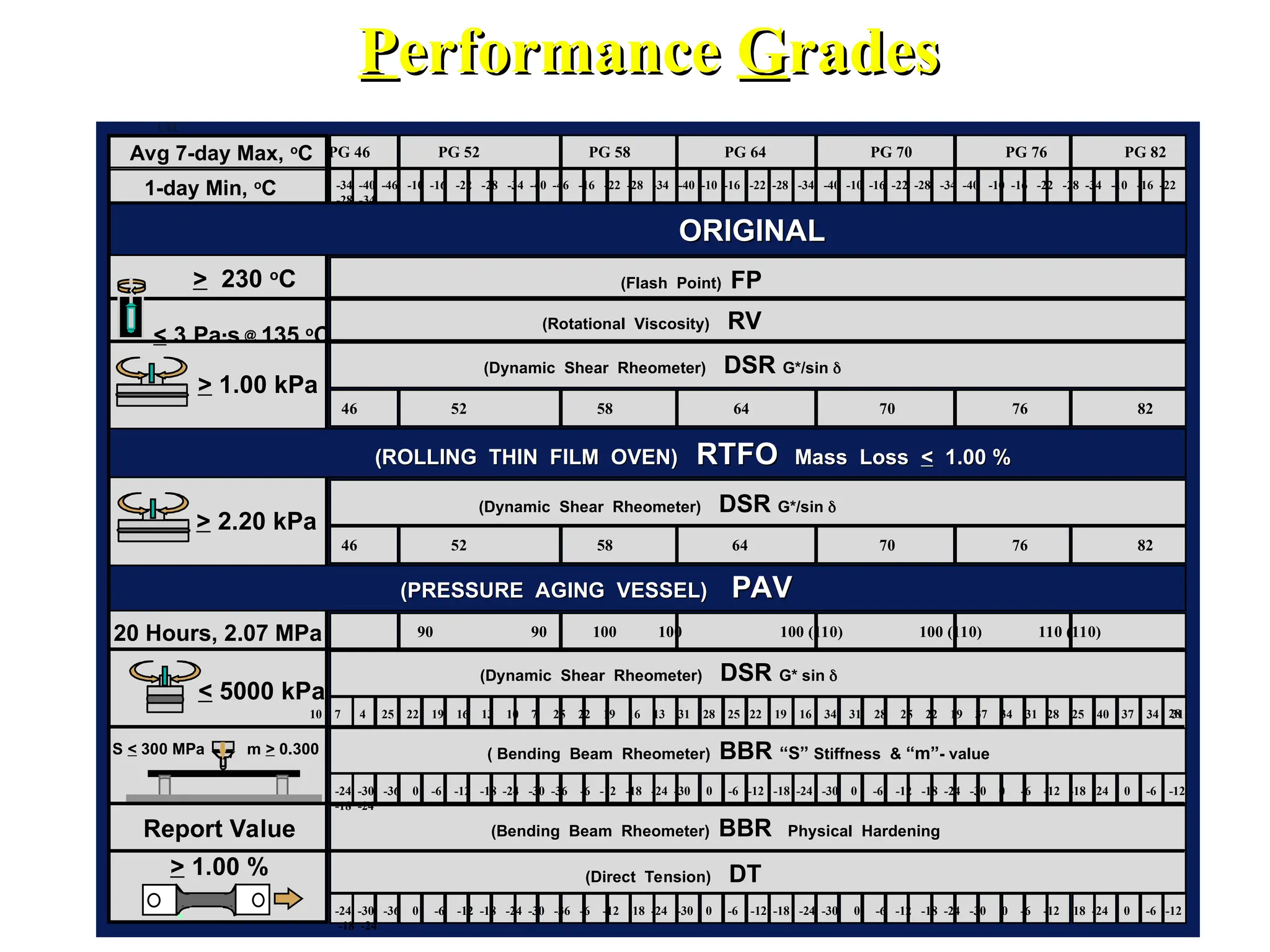

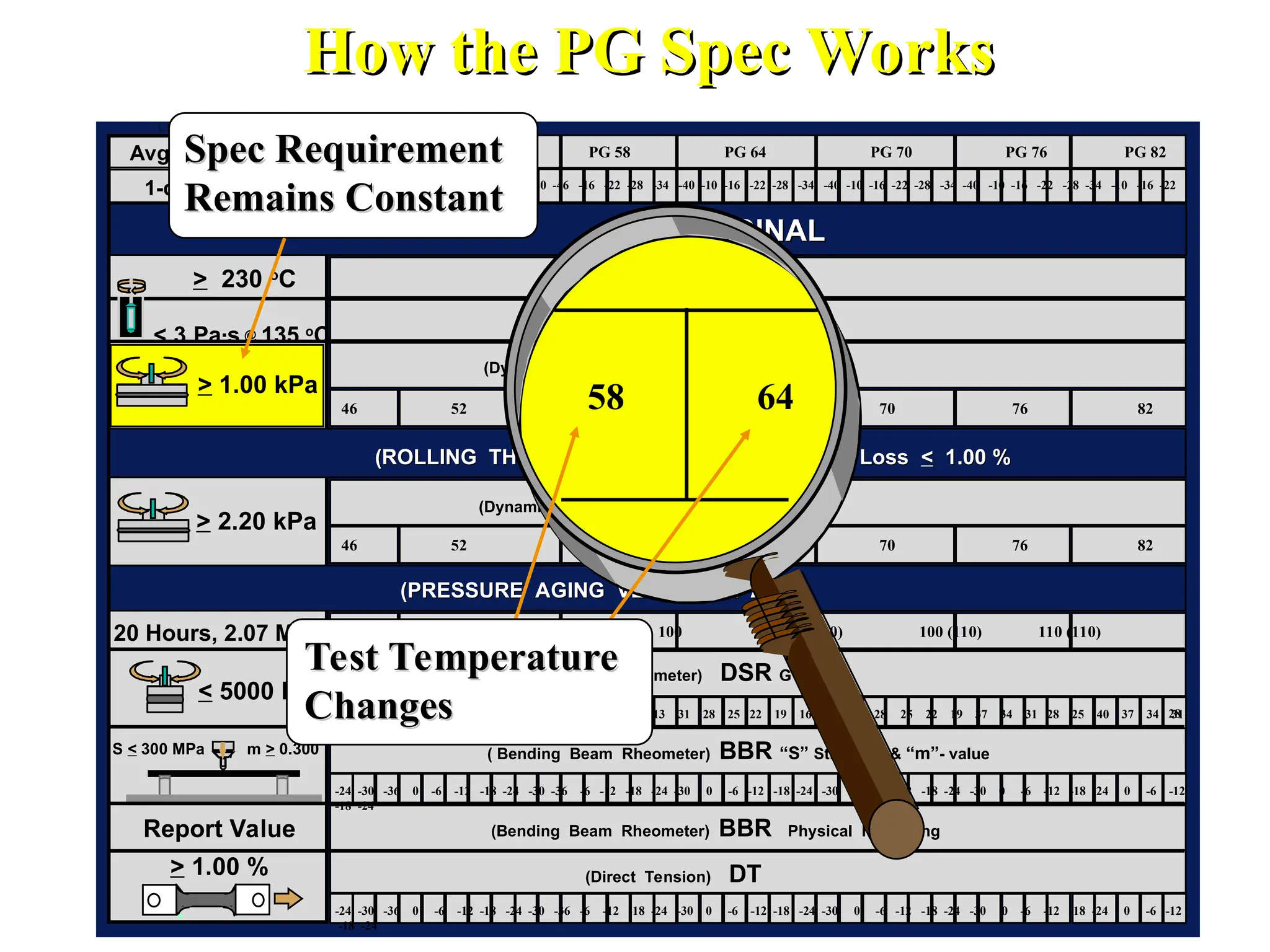

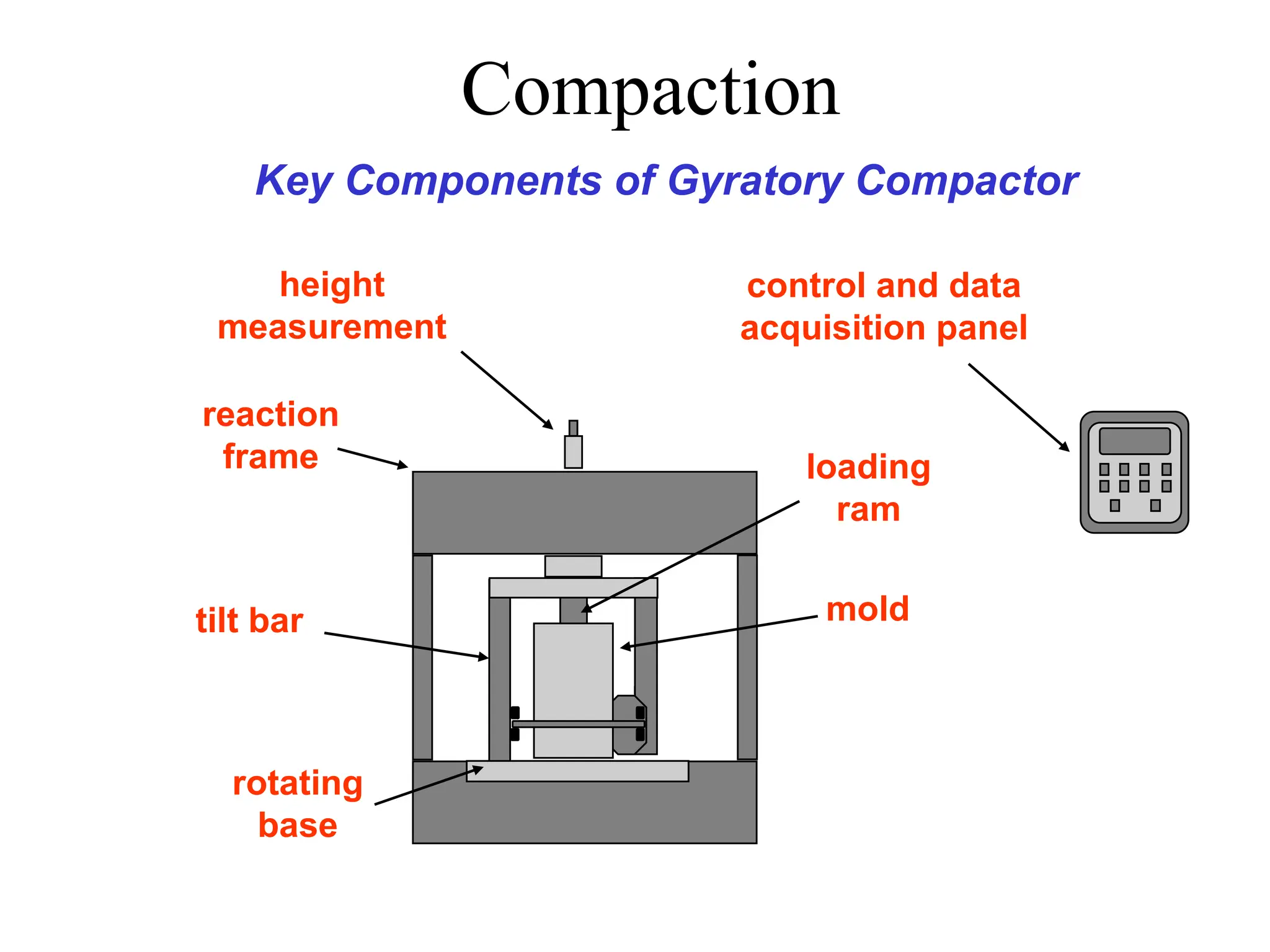

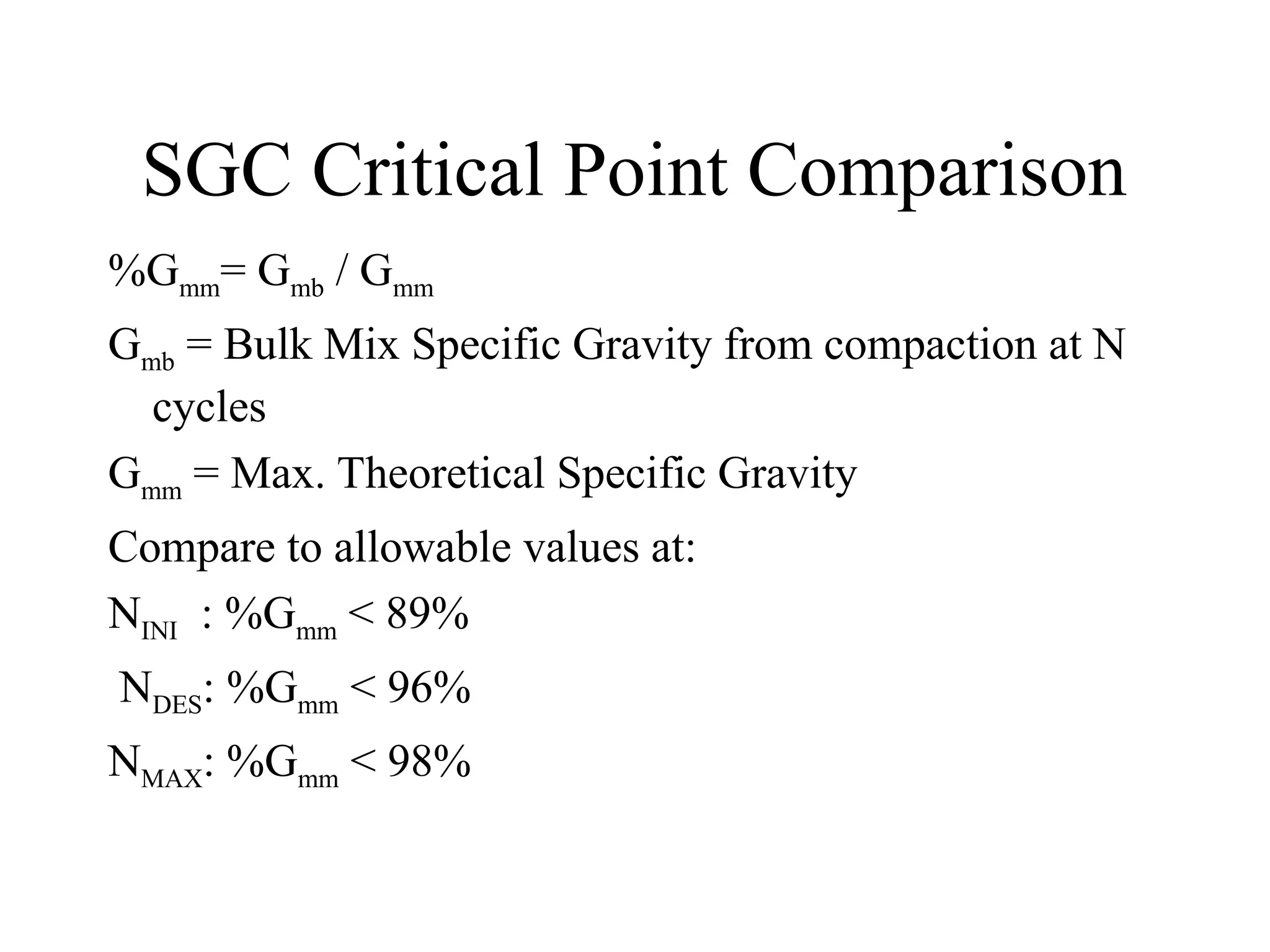

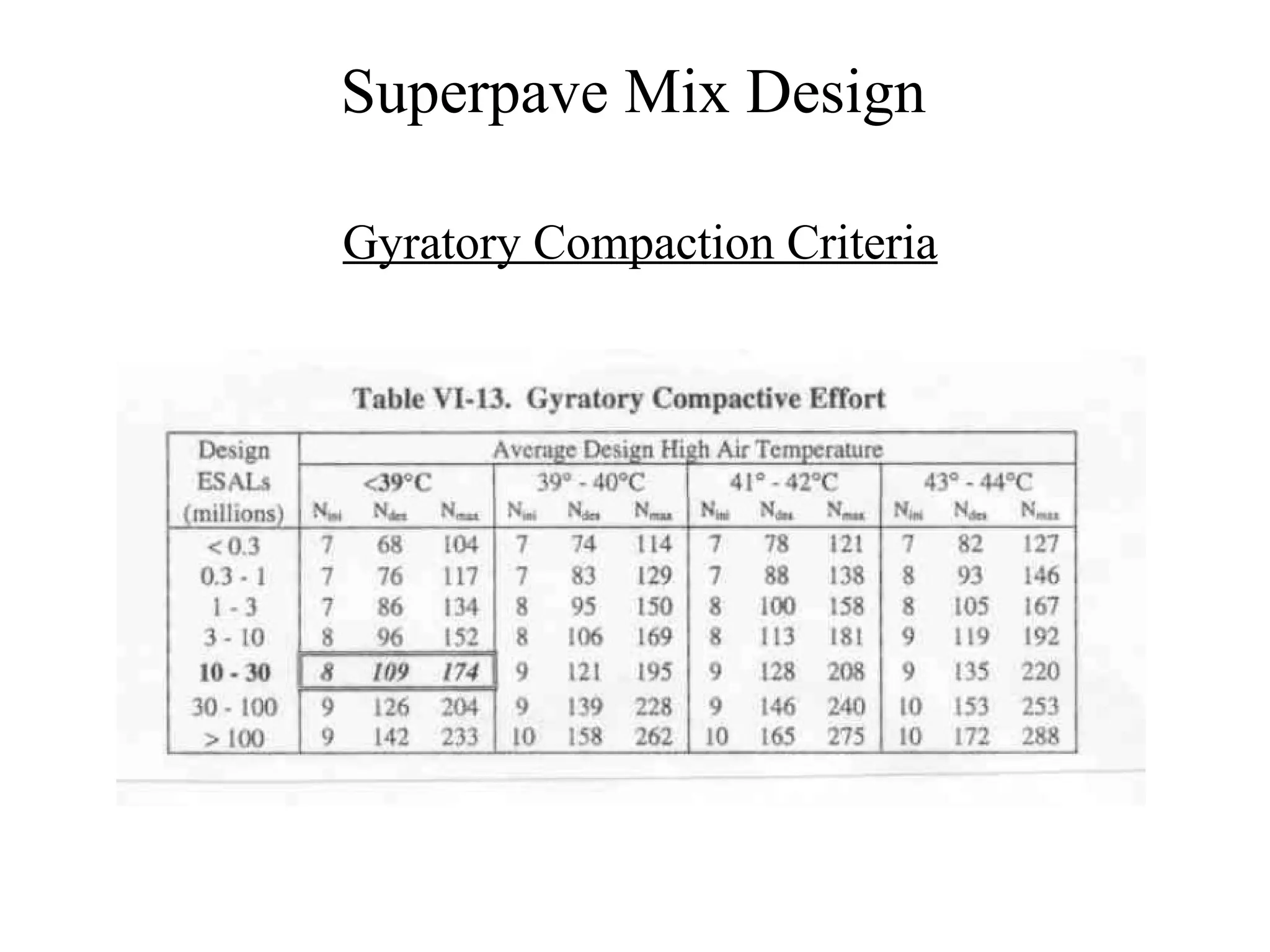

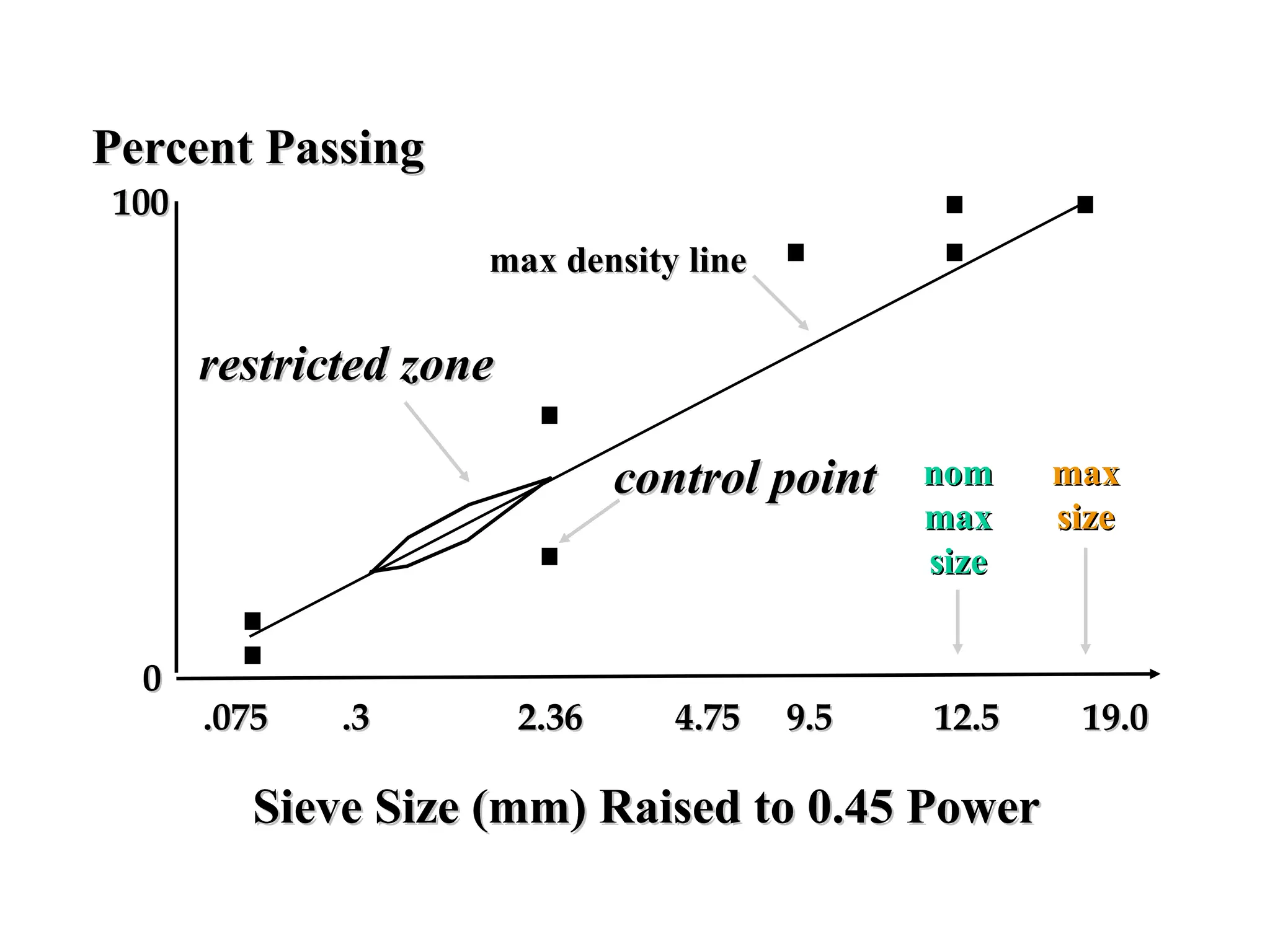

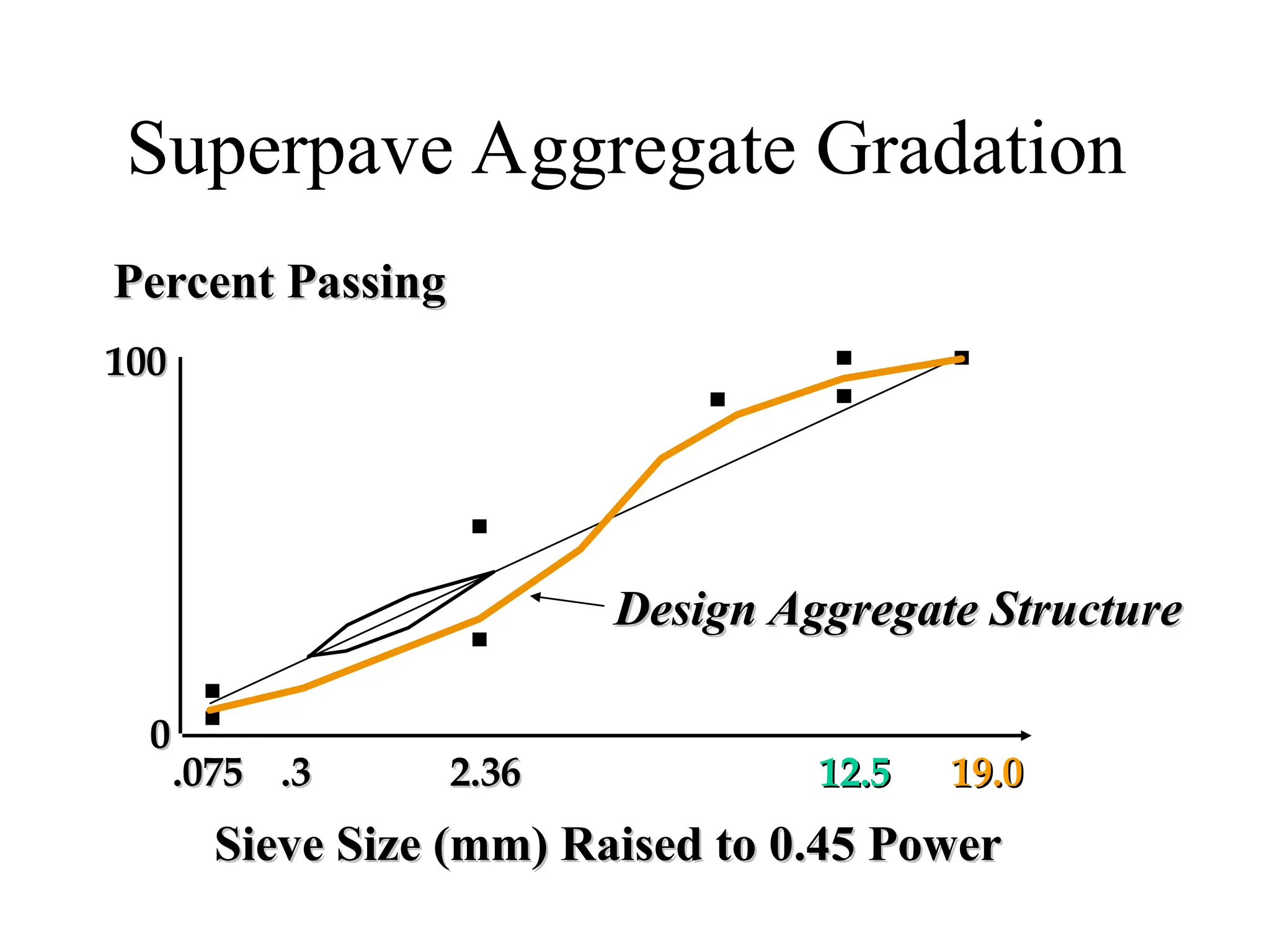

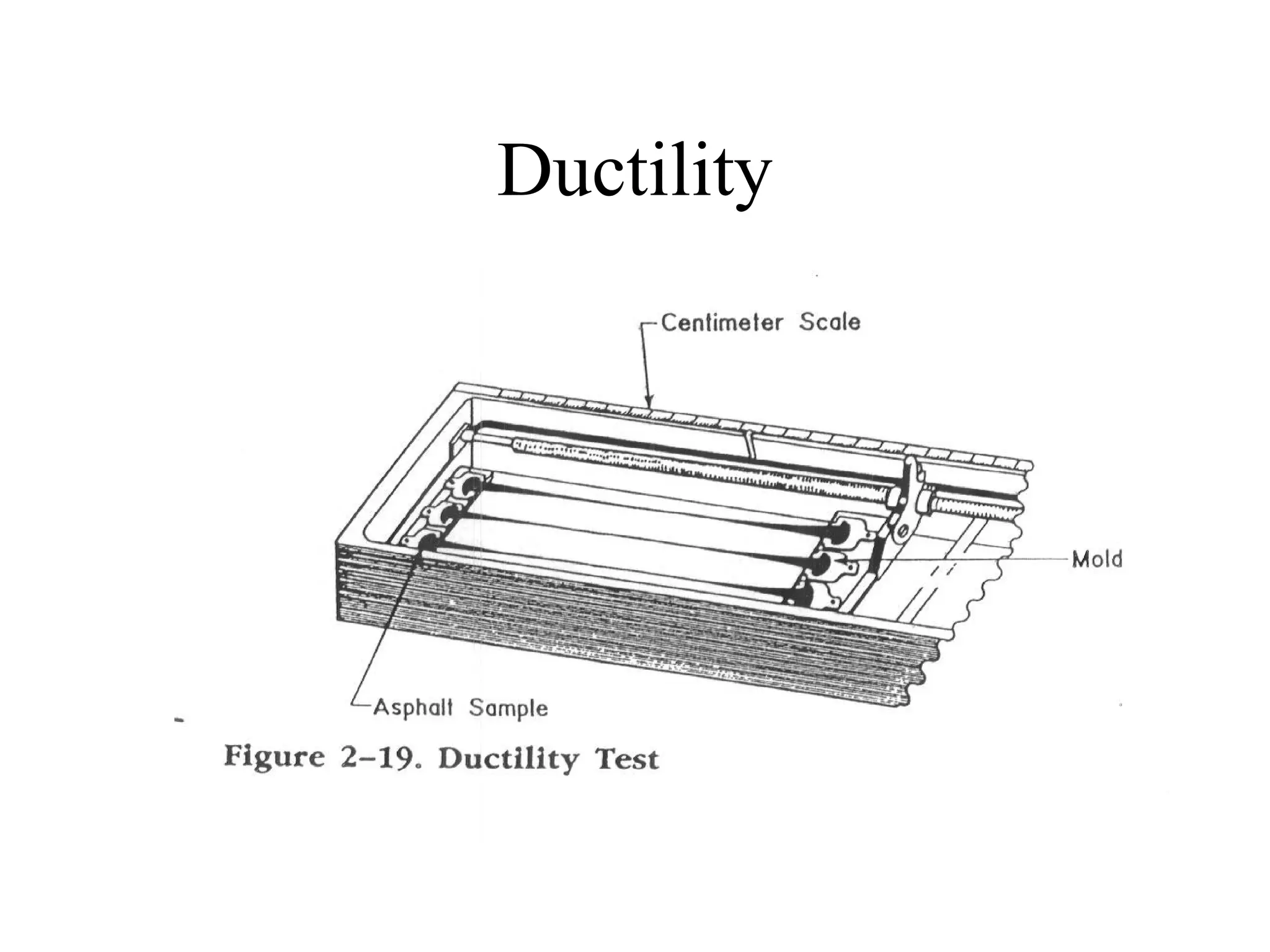

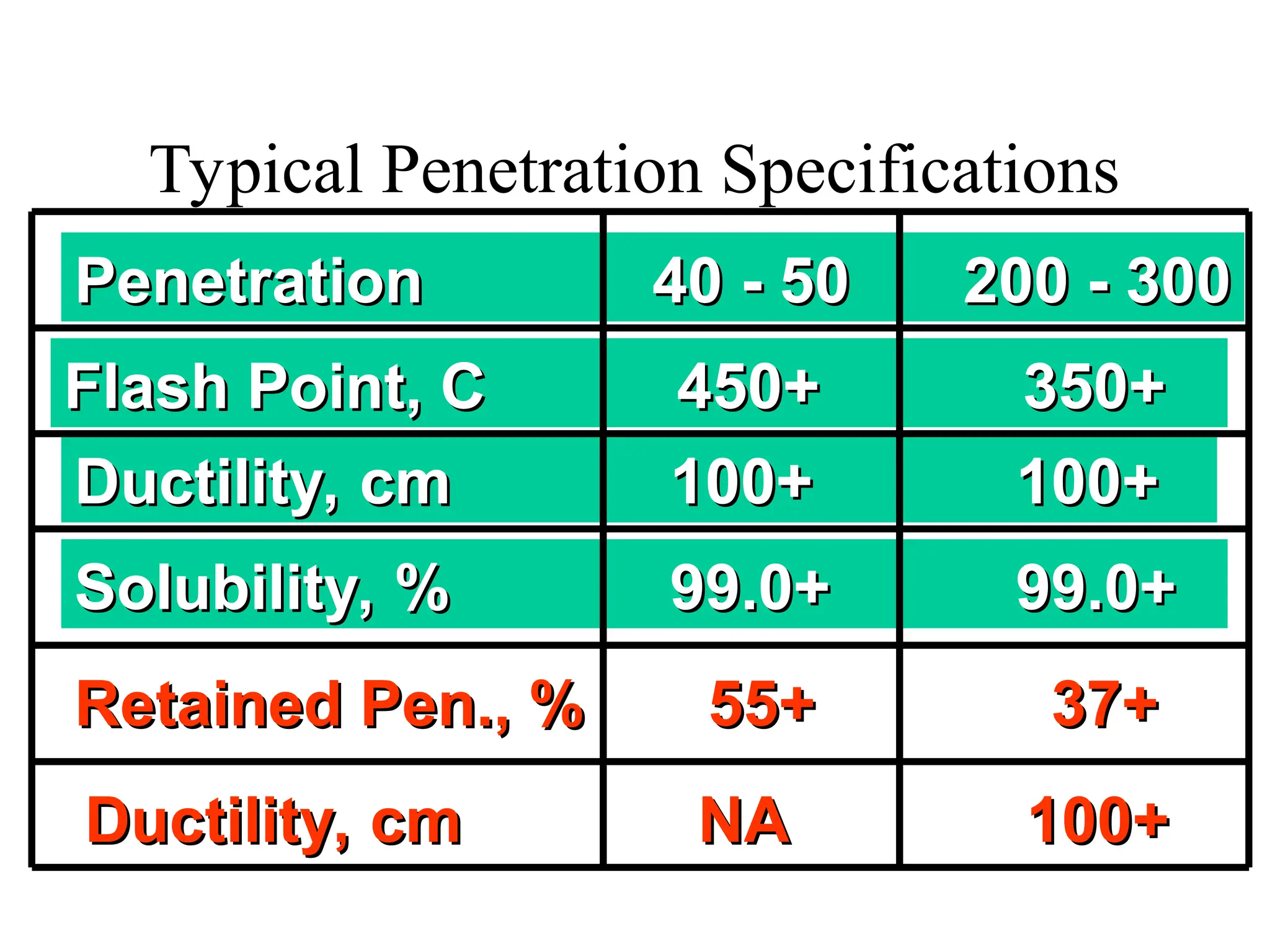

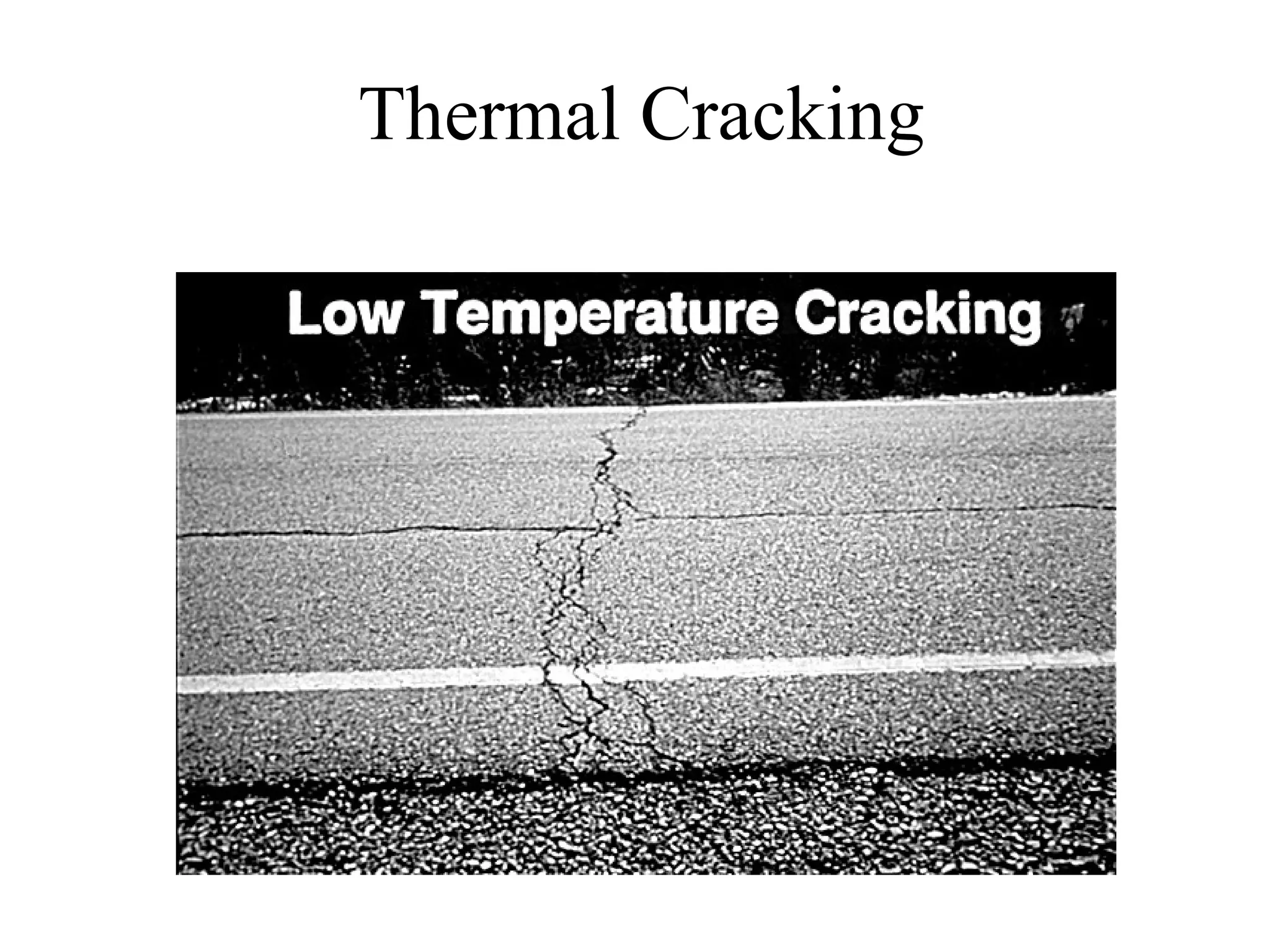

The document outlines FHWA's Superpave asphalt specifications, detailing aggregate classifications, grading systems, and performance grading methods for asphalt binders. It emphasizes the importance of aggregate size and the impact of various factors on pavement performance, including high and low-temperature behaviors, and testing methods for determining properties of asphalt mixes. Key topics include mix design history, Superpave requirements for durability, stability, and workability, alongside guidelines for asphalt cement selection and testing to ensure quality in asphalt concrete pavements.

![Summary

Fatigue

Cracking

Rutting

RTFO

Short Term Aging

No aging

Construction

[RV]

[DSR]

Low Temp

Cracking

[BBR]

[DTT]

[DTT]

PAV

Long Term Aging](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3806583-240912125607-2164b4a2/75/Super-pave-tested-and-Design-for-road-ppt-37-2048.jpg)