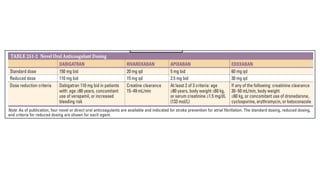

The document discusses stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF), emphasizing continuous anticoagulation therapy as a key approach, especially for high-risk patient populations. It details scoring systems for assessing stroke and bleeding risks, the efficacy of various anticoagulants, and the considerations for cardioversion in AF management. Additionally, it highlights the potential complications of anticoagulation therapy and the importance of balancing stroke and bleeding risks in treatment decisions.

![Warfarin can be an inconvenient agent that

● requires several days to achieve a therapeutic effect (prothrombin time

[PT]/international normalized ratio [INR] >2),

● requires monitoring of PT/INR to adjust dose, and

● has many drug and food interactions that can hinder patient compliance

and render maintaining a therapeutic effect challenging.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strokepreventioninaf-240717023800-74edbe41/85/Stroke-Prevention-in-Atrial-Fibrillation-pdf-10-320.jpg)