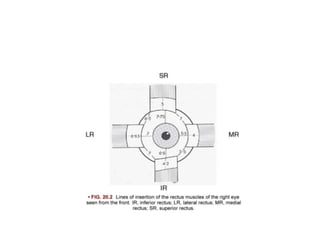

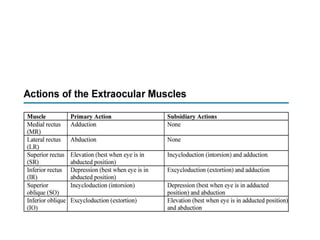

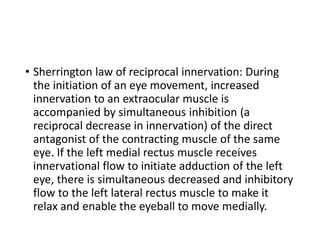

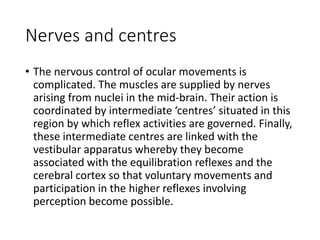

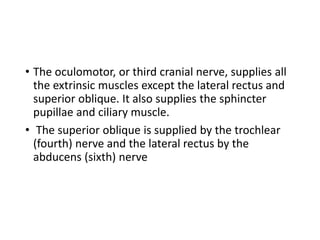

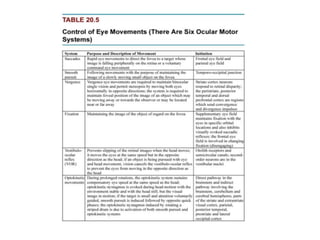

The document summarizes the motor apparatus of the eye including the extraocular muscles, their actions, innervation and coordination for binocular vision. It describes the positioning and movement of the eyes, convergence and accommodation reflexes, and grades of binocular single vision including fusion and stereopsis. The extraocular muscles work in synkinesis to move the eyes conjugately or disjunctively according to Hering's and Sherrington's laws of innervation.