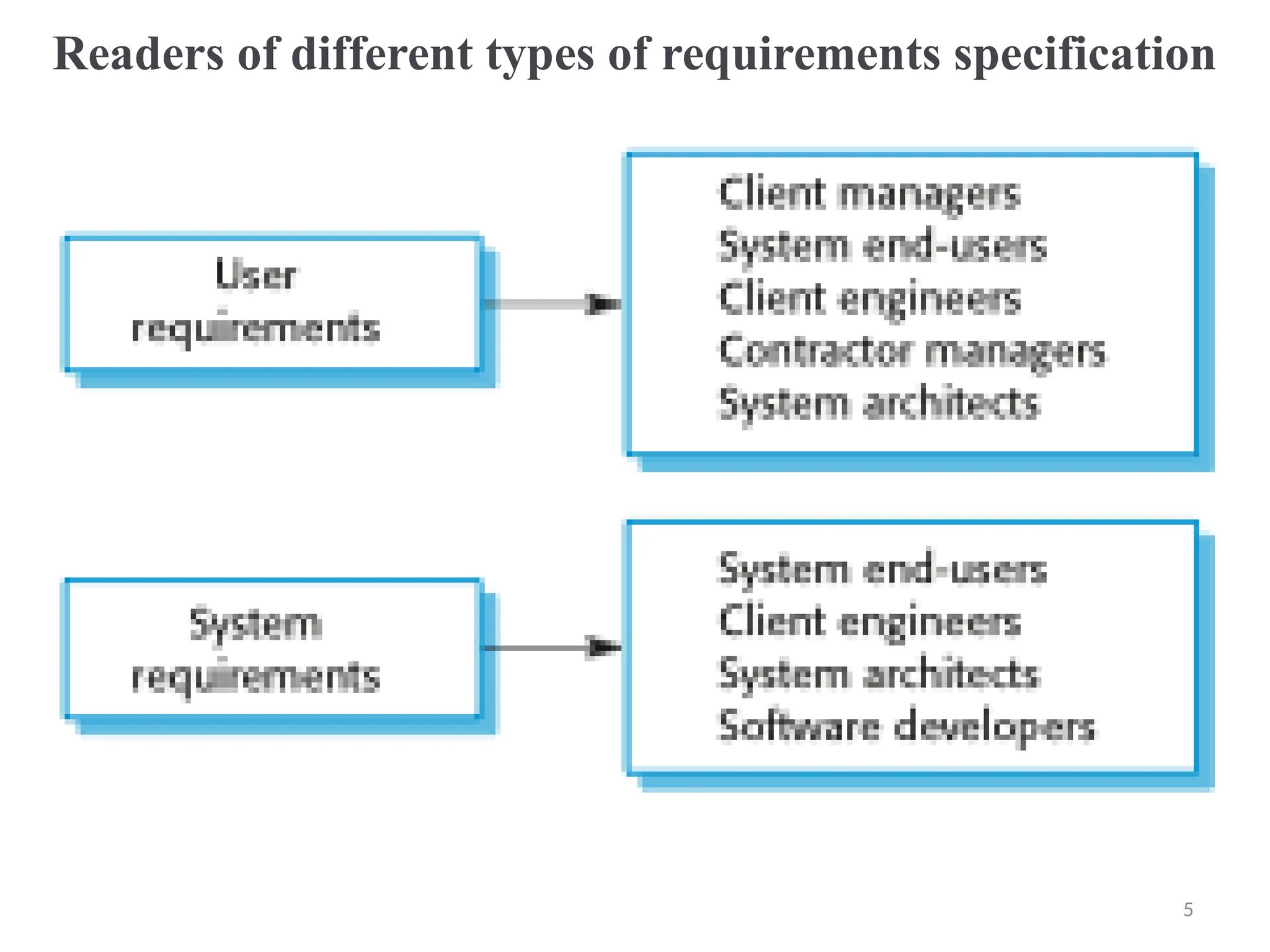

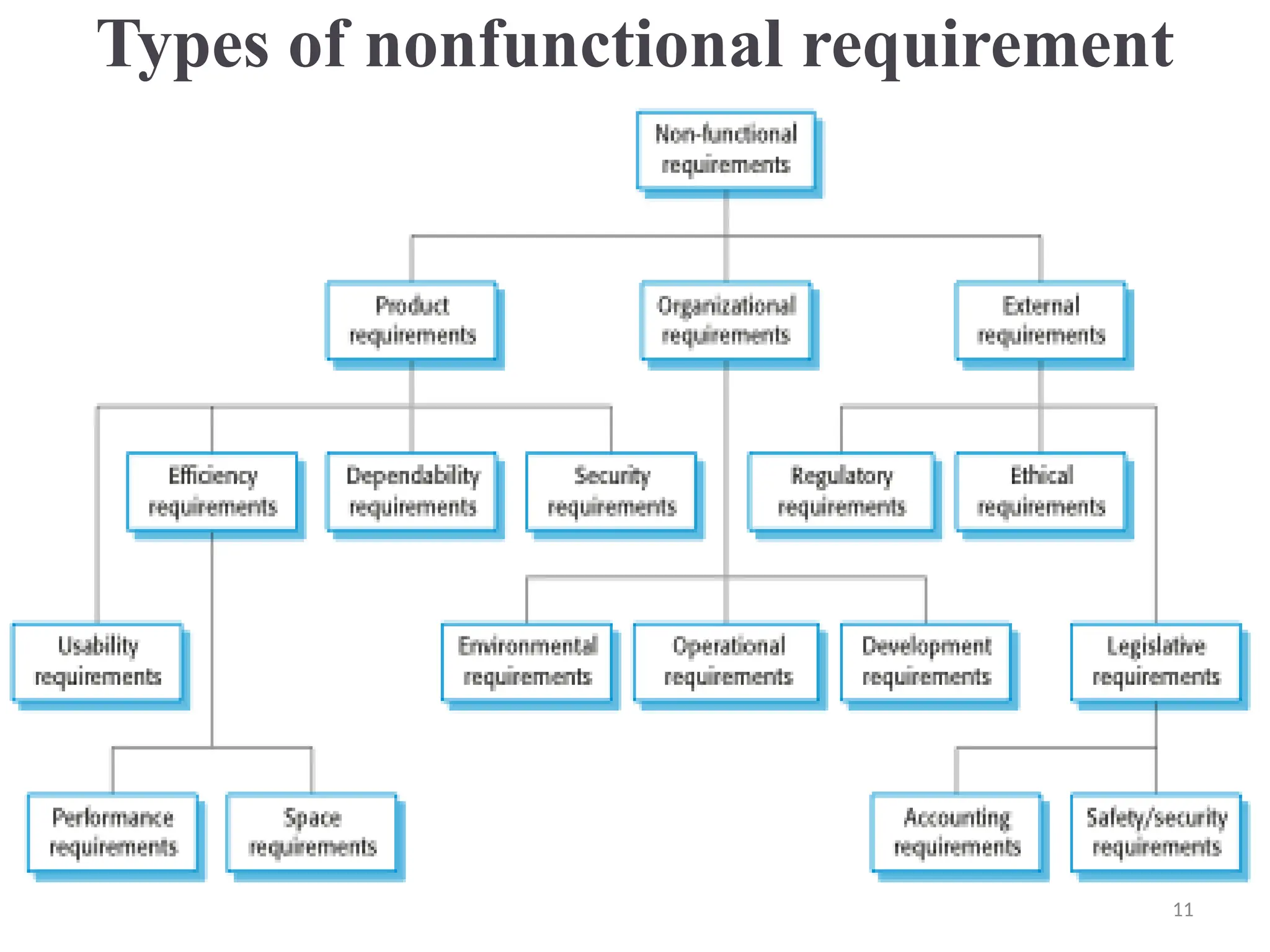

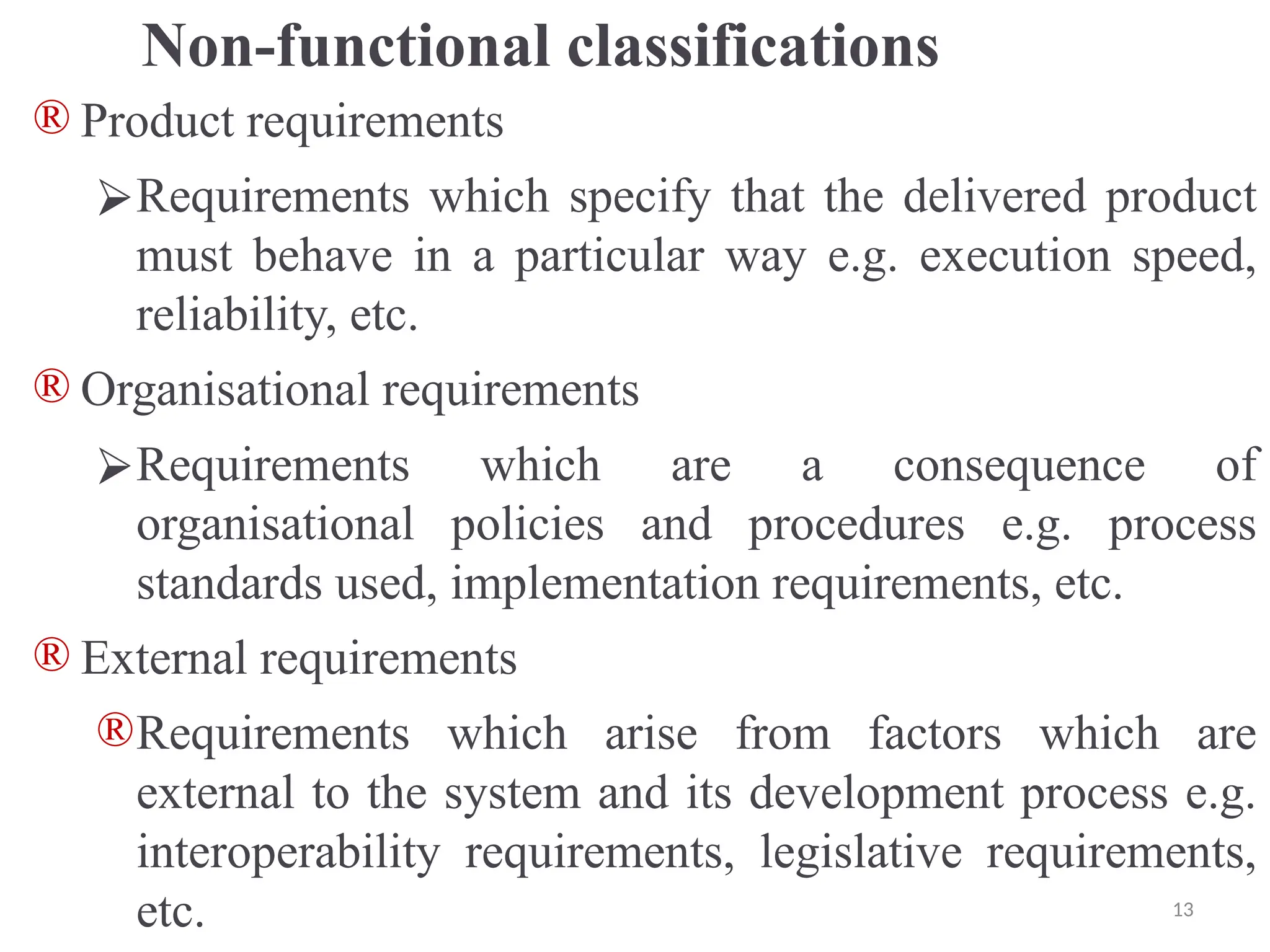

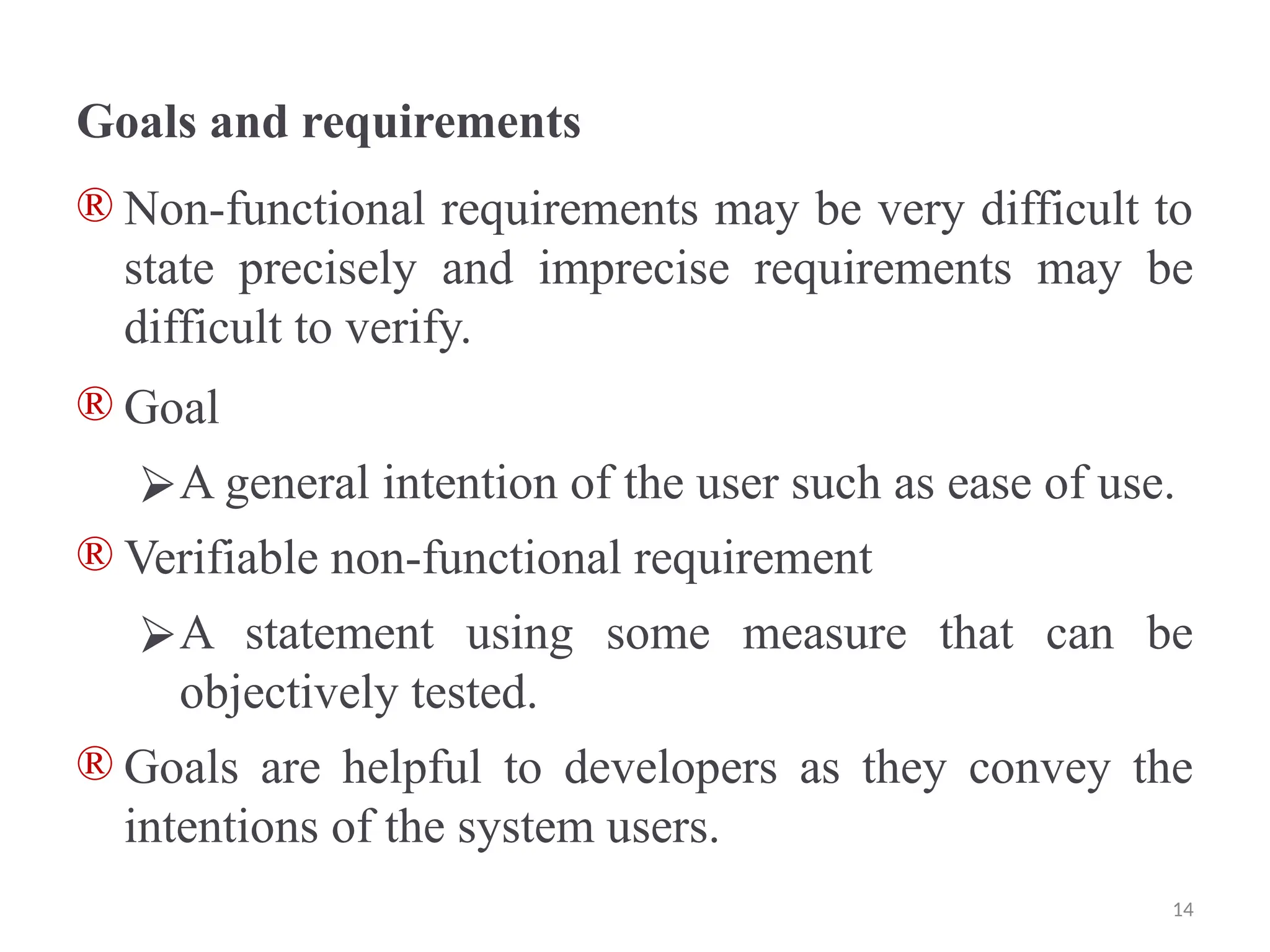

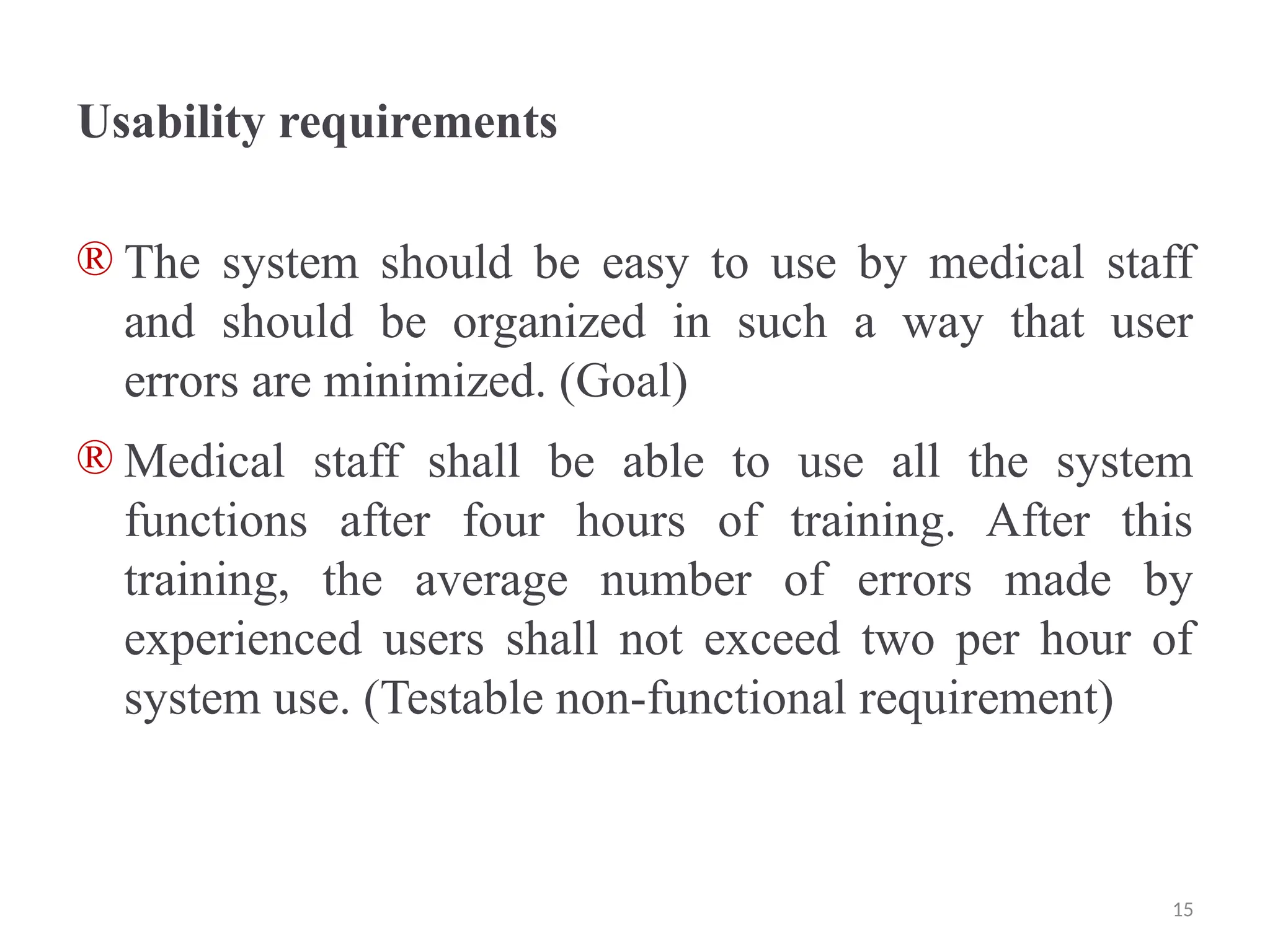

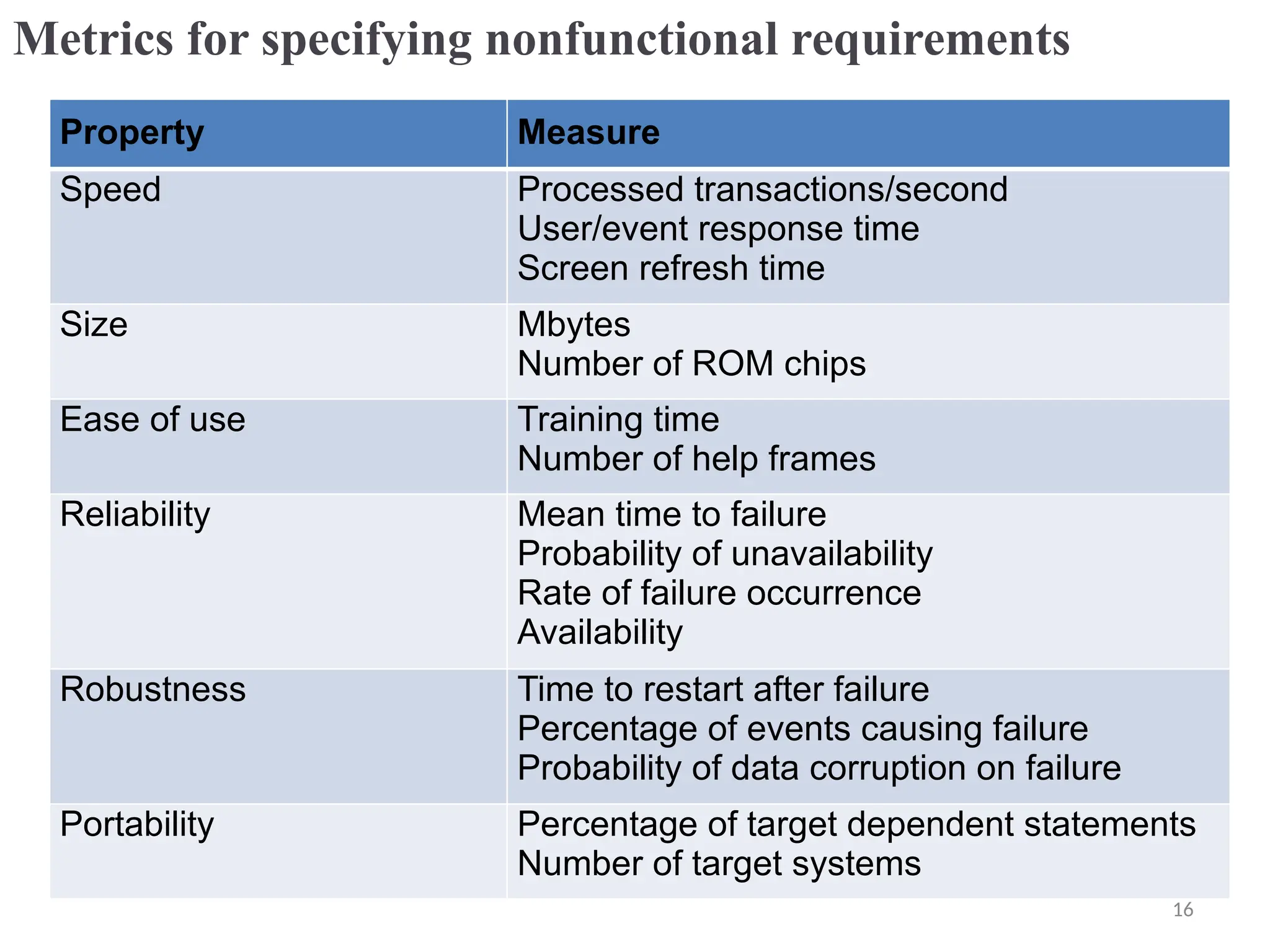

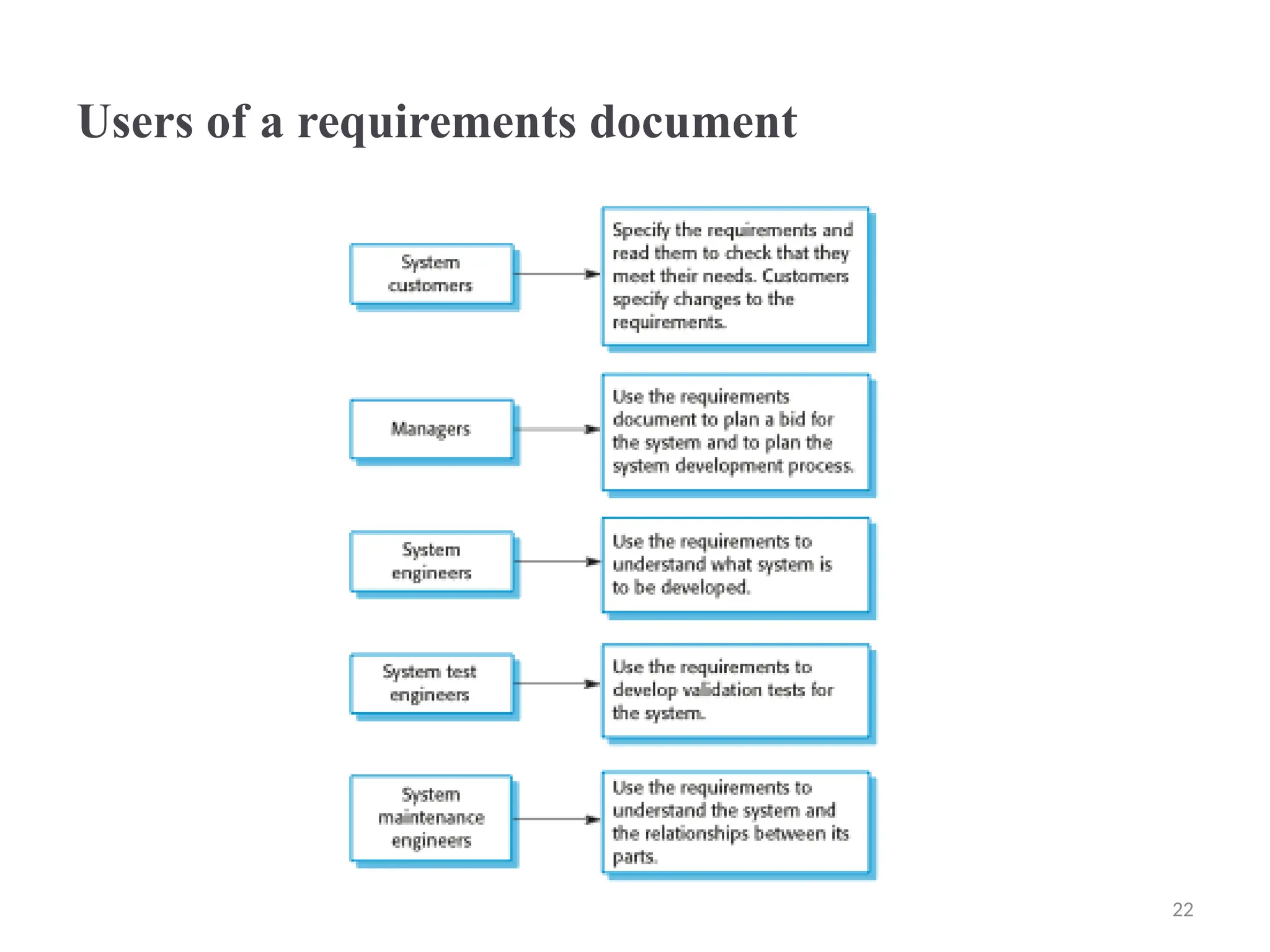

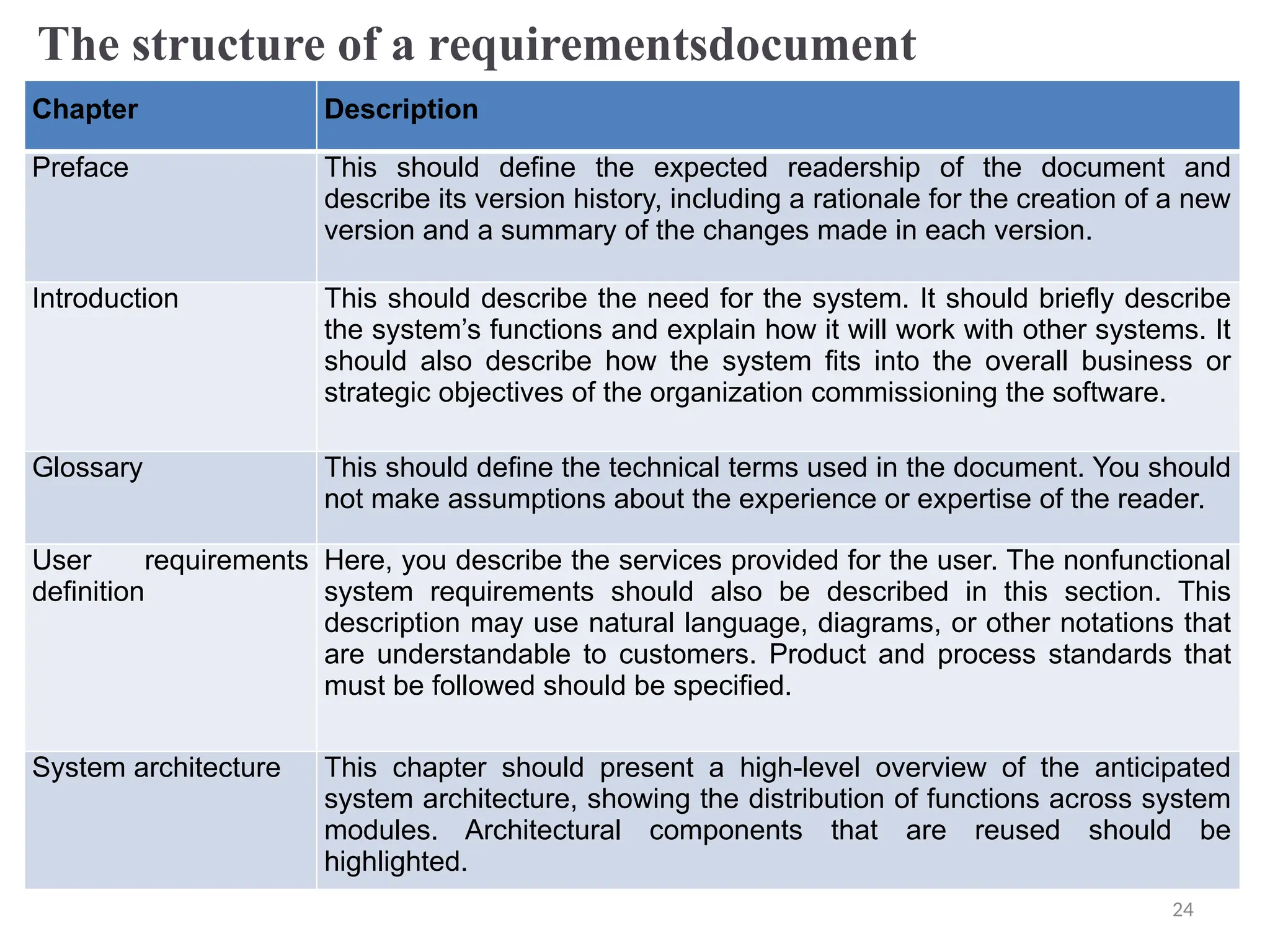

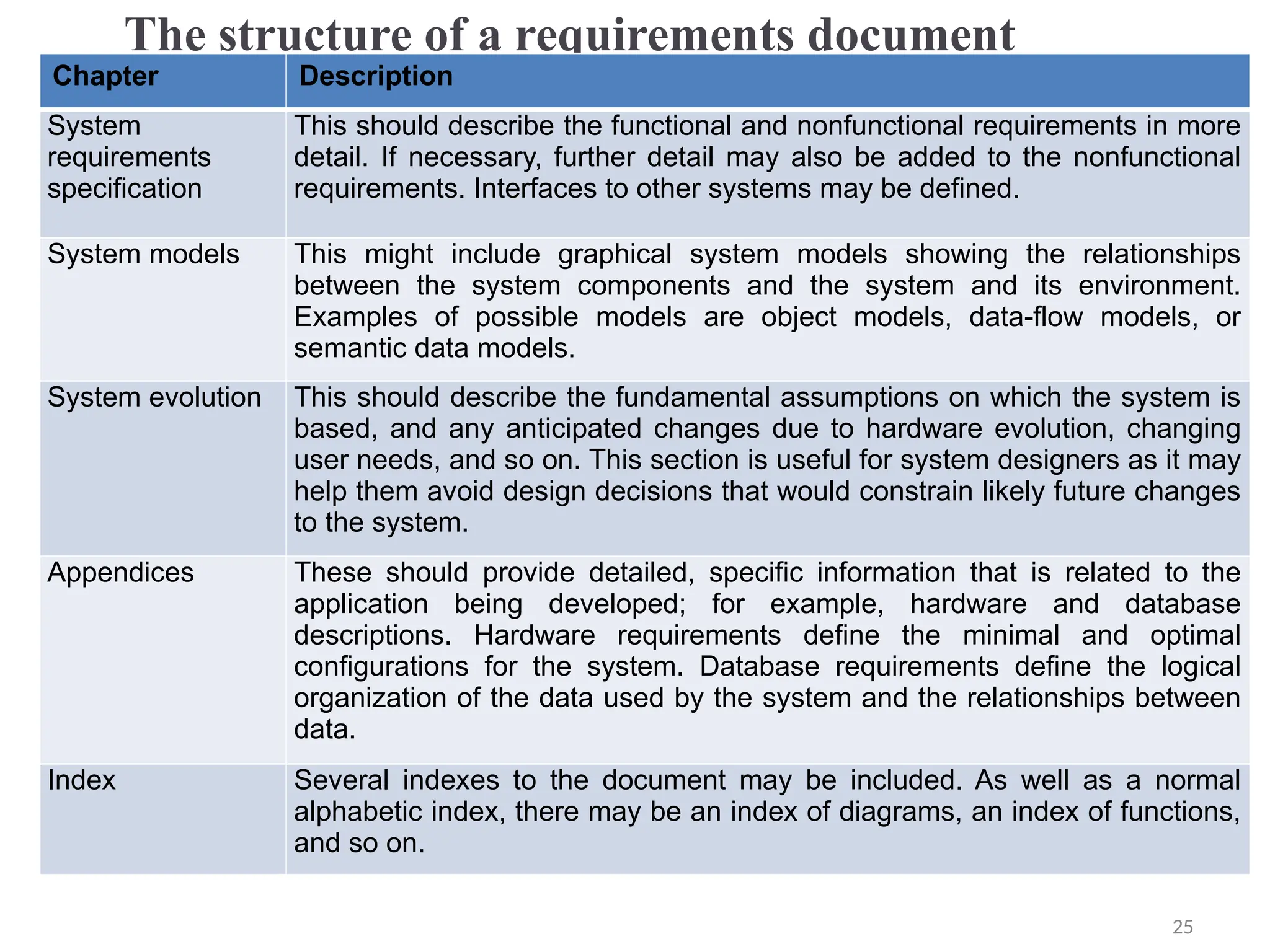

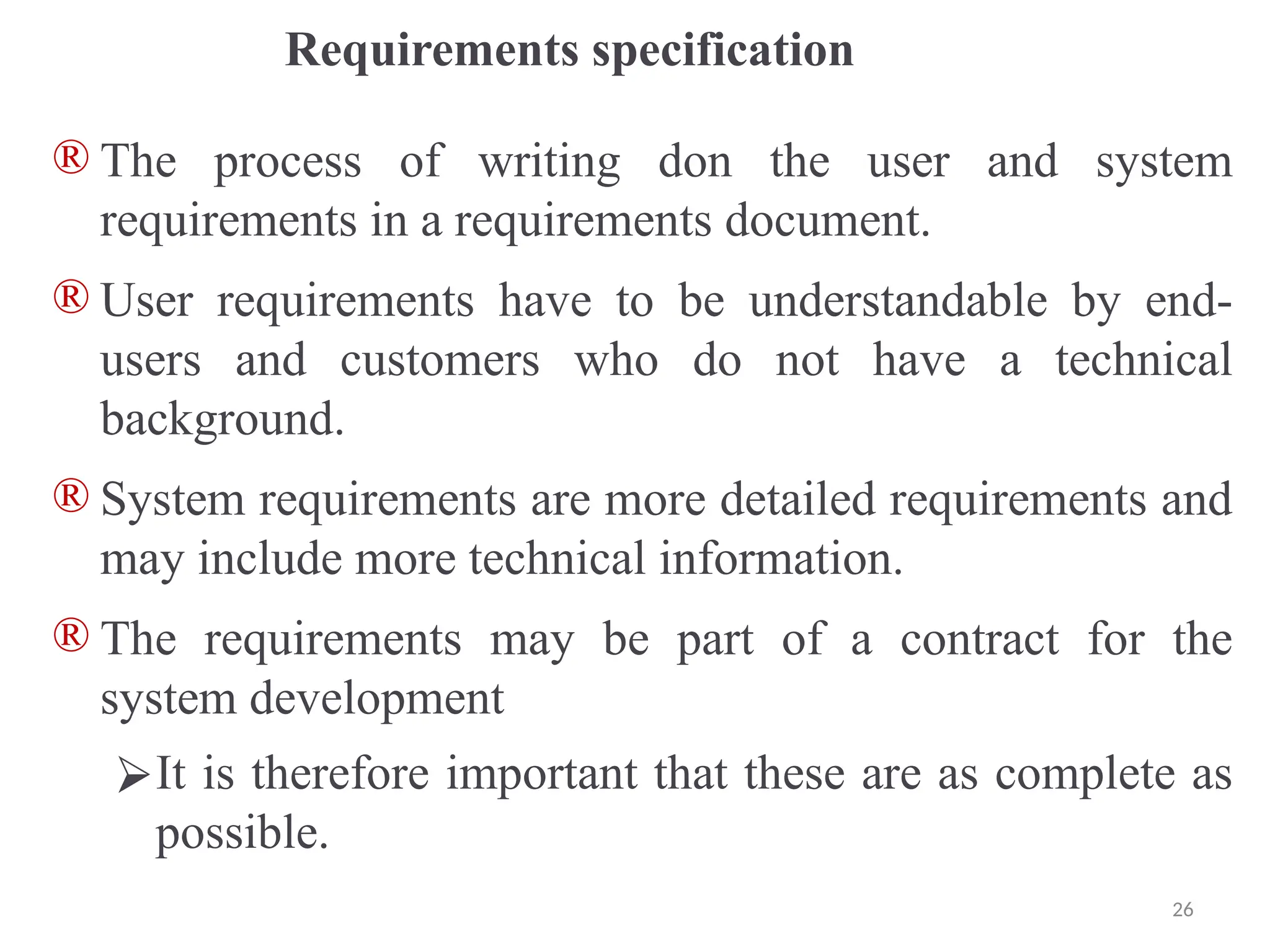

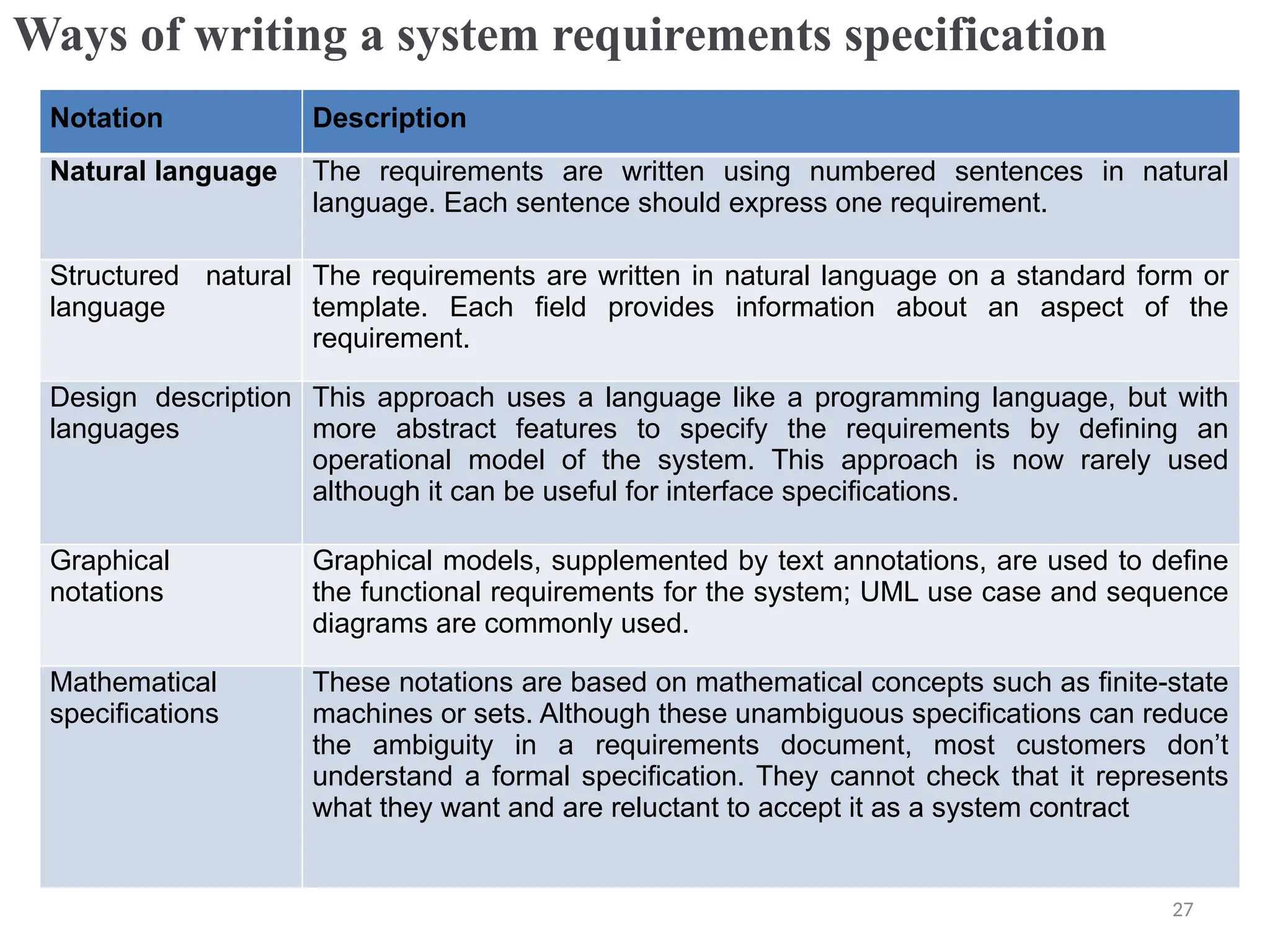

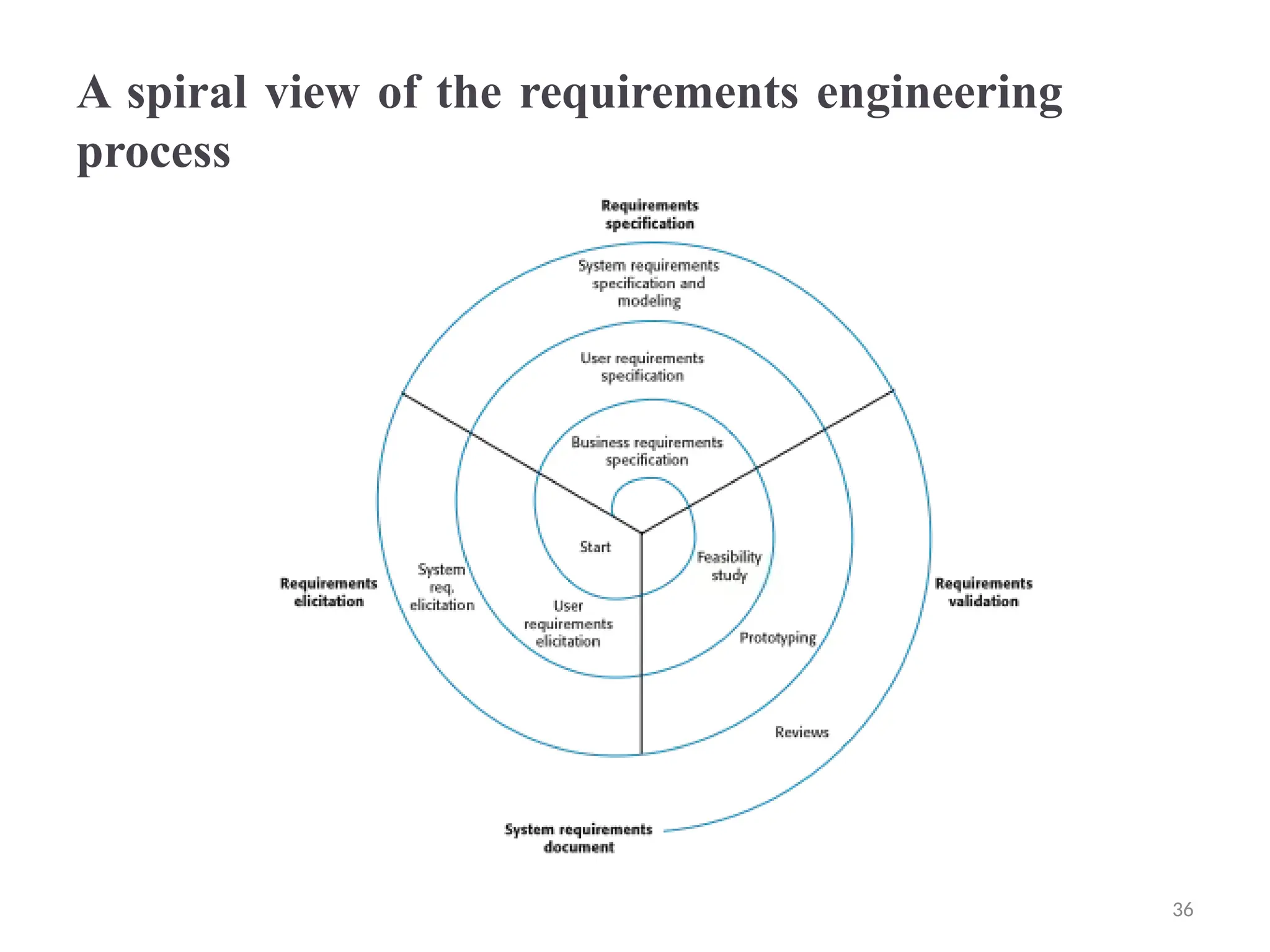

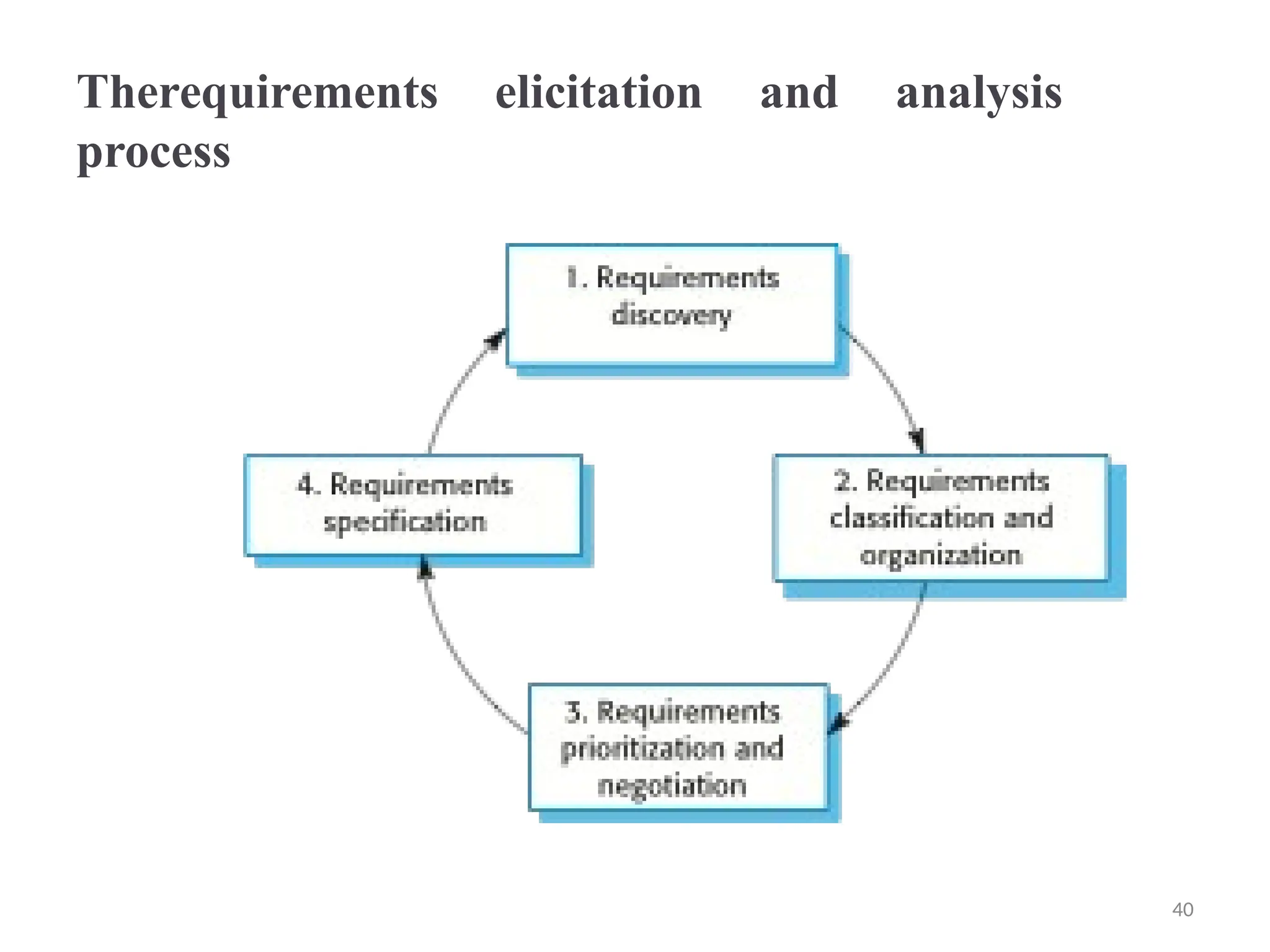

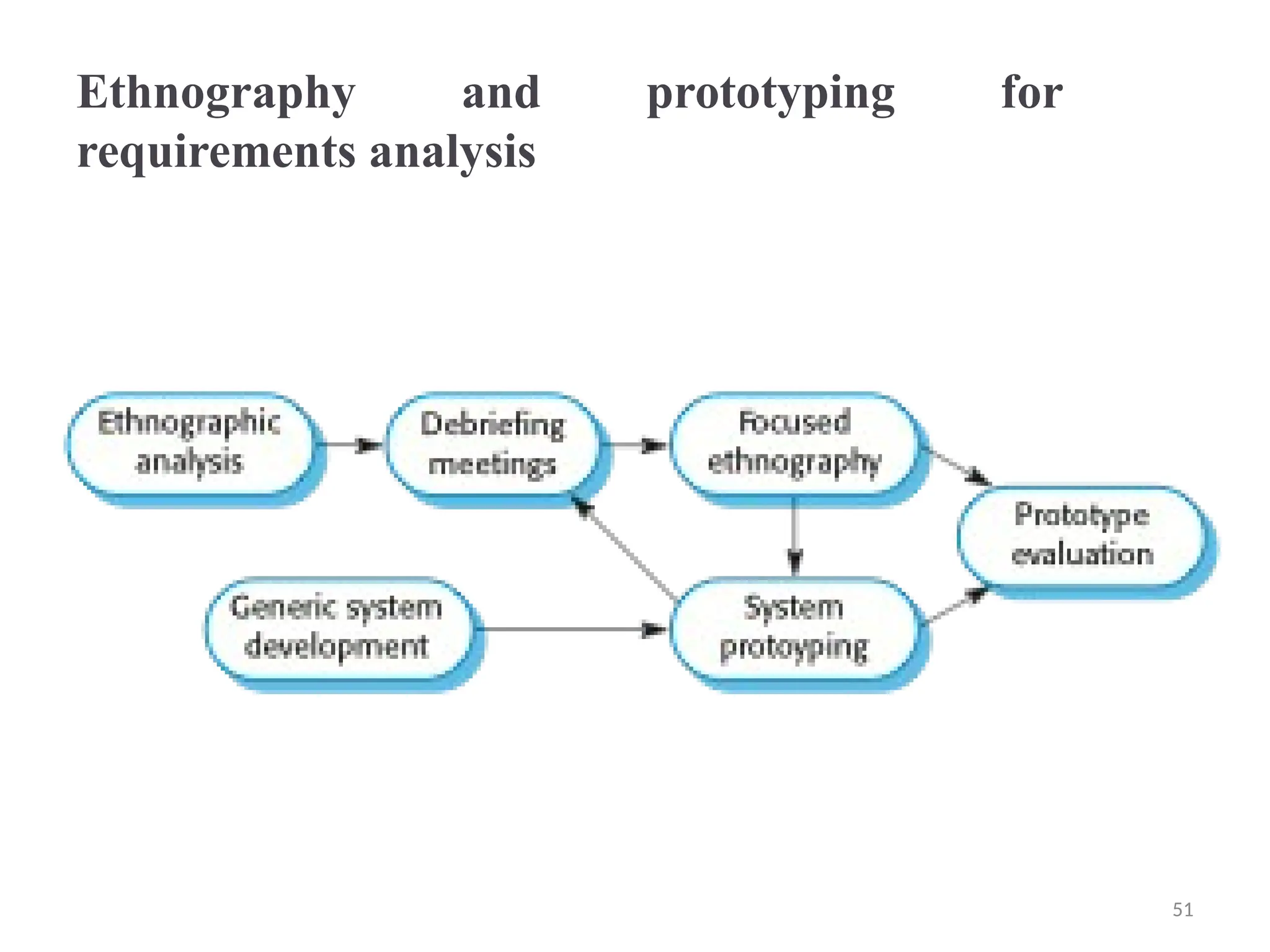

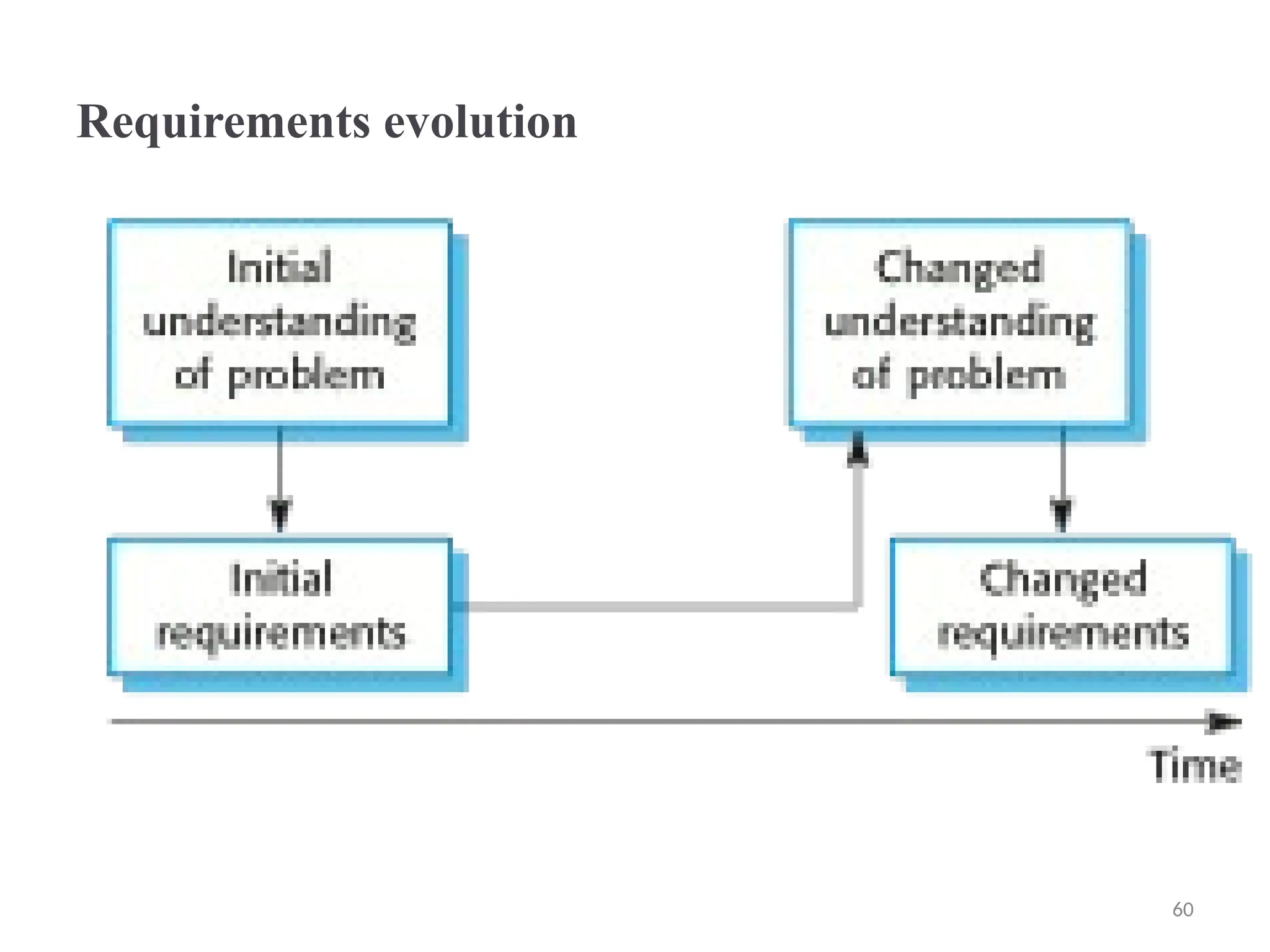

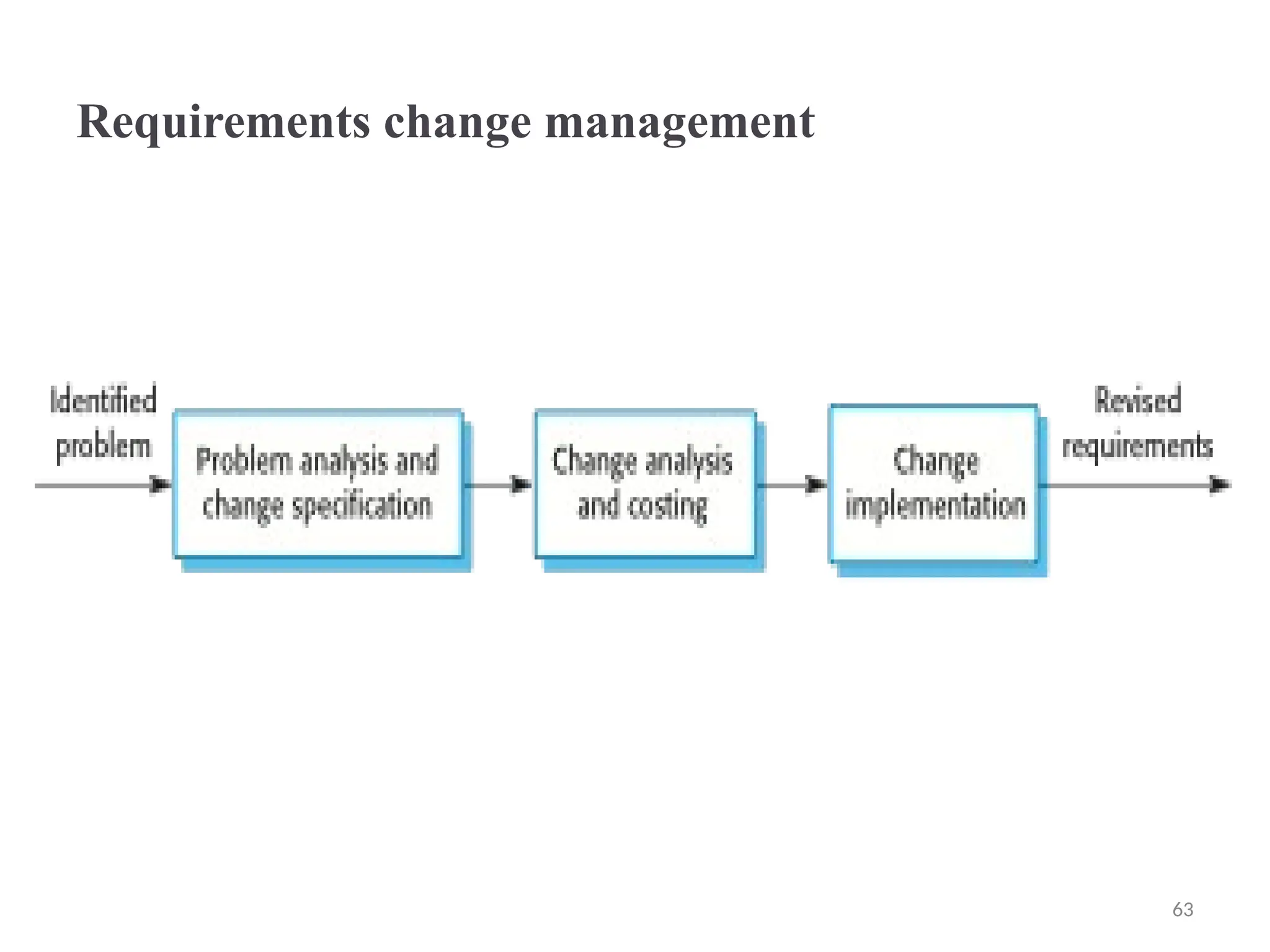

The document covers the fundamentals of requirements engineering, elaborating on functional and non-functional requirements, the software requirements document, and the processes involved in requirements elicitation and management. It highlights the challenges of specifying requirements, ensuring completeness and consistency, as well as the importance of understanding different types of requirements for effective system development. Additionally, it addresses the significance of stakeholder interactions in defining what a system should do while acknowledging the complexities and potential ambiguities in the requirements gathering process.