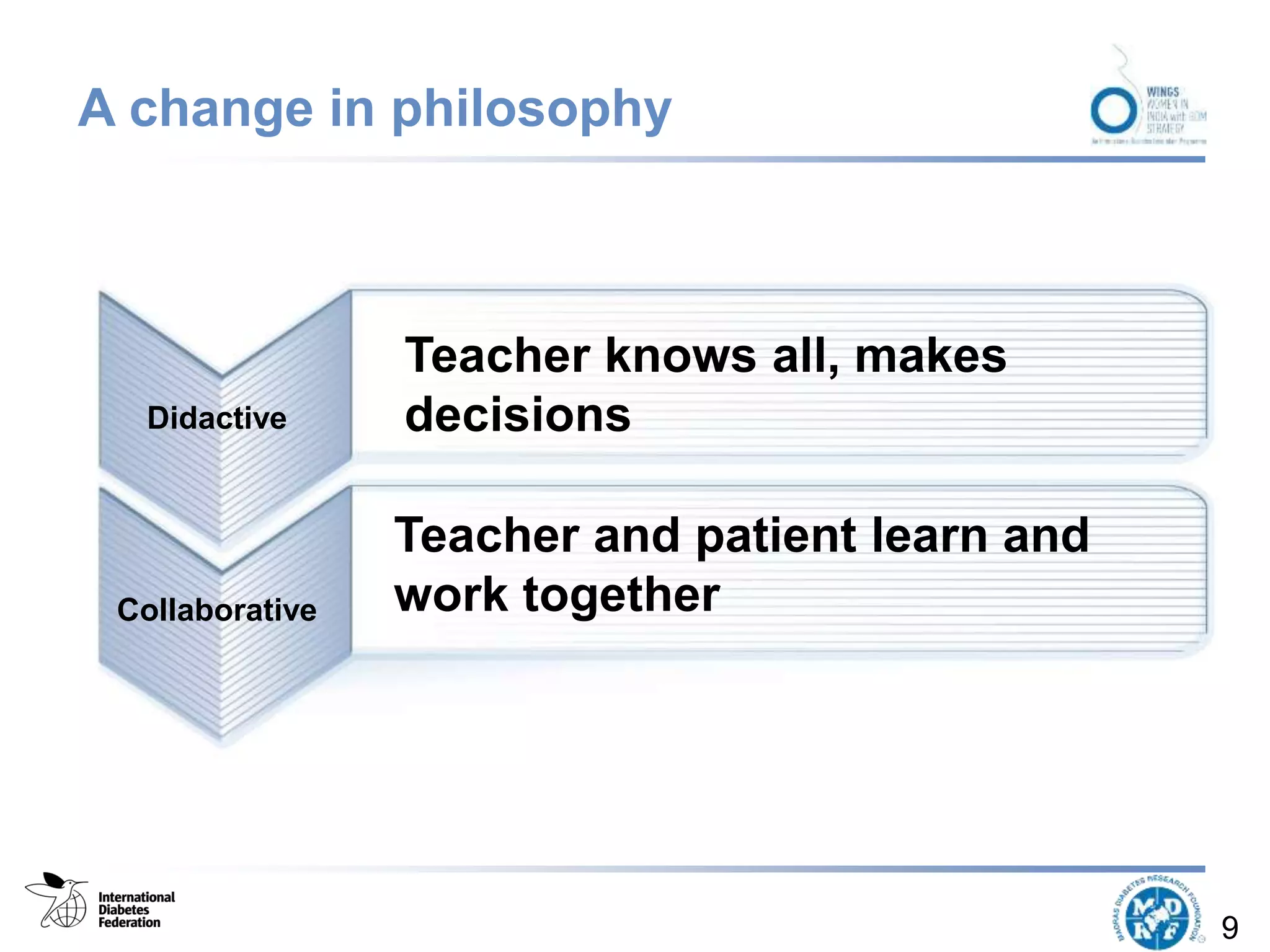

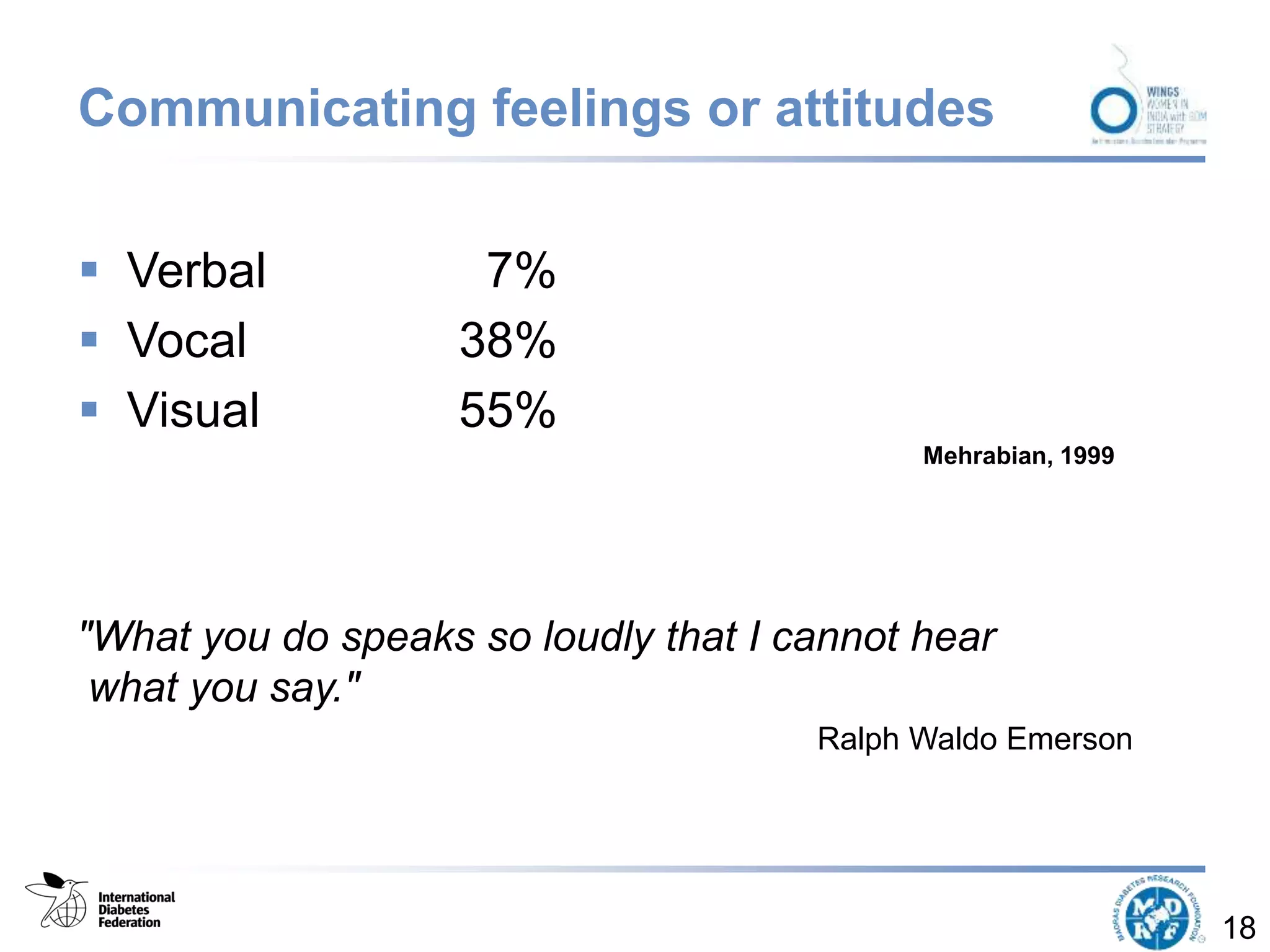

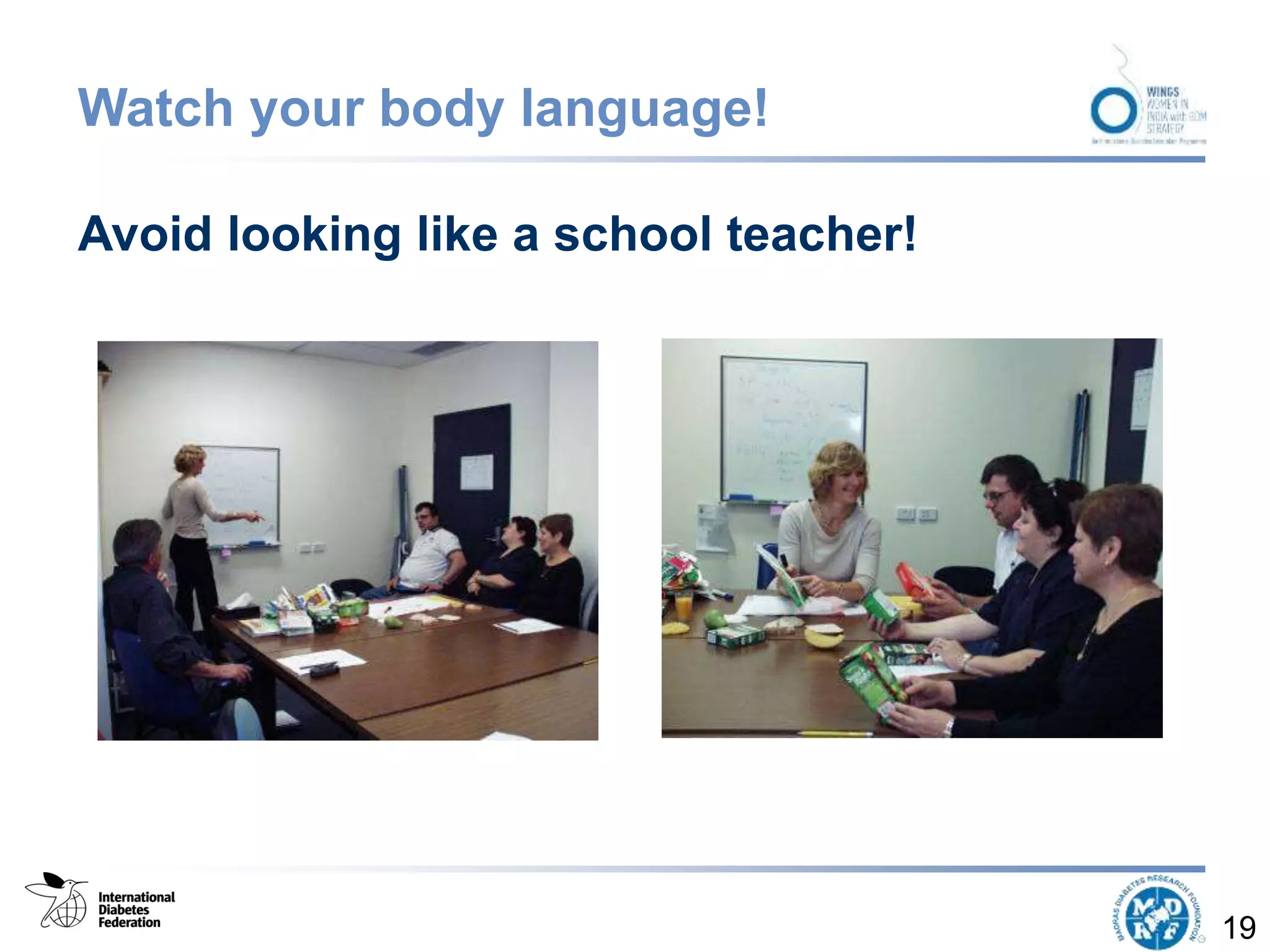

The document outlines the objectives and importance of self-management education for women with gestational diabetes, emphasizing the need for personalized, effective diabetes care and informed decision-making. It discusses strategies to promote active self-management, including communication skills, assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation of education efforts. The findings highlight that ongoing support and tailored education interventions significantly enhance health outcomes for women managing gestational diabetes.